Photographs and scans by the author, except for the historic view of the church interior, taken from the church website by kind permission of the present incumbent, the Revd Canon Stephen Evans, who was also very helpful when I visited the church. Many thanks also to Jill Armitage, who later sent in some helpful information about her forebear, Edward Armitage. You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer or source, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [Click on all the images to enlarge them.]

The Two Earliest Churches

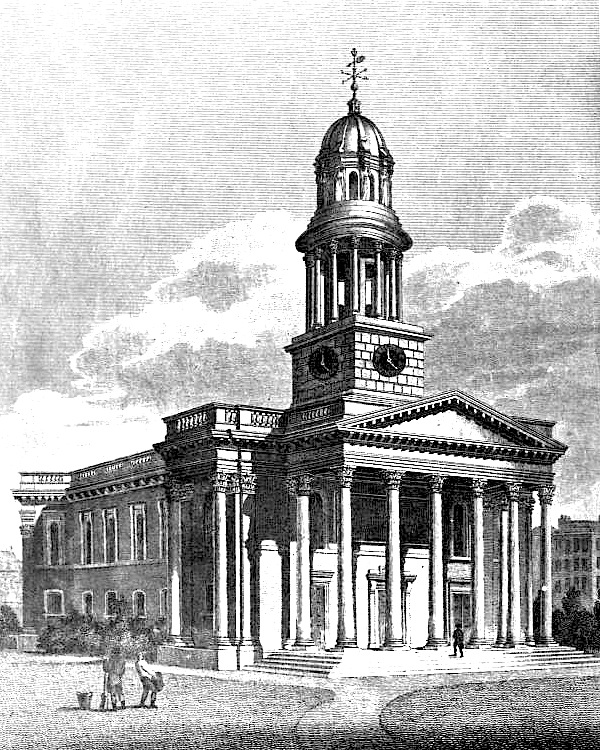

The old (i.e., second) parish church. Source: Clinch 17.

Marylebone's parish church has a long and interesting history. The very earliest church to serve the parish was not dedicated to St Mary, but to John the Evangelist, and was located further south, in what is now the Marble Arch area. But the second parish church, dating from 1400, was St Mary by the "burn" or "bourne" — the lost River Tyburn, where the village was growing up further north. Its name gradually evolving into to St Marylebone, this church was built on the site of the present memorial park towards the end of Marylebone High Street. It lasted several centuries. Francis Bacon was married there in 1606, and much later on the interior provided the setting for the fifth canvas of Hogarth's Rake's Progress (1732-33). This is where Hogarth depicts a farcical wedding ceremony, through which the rake attempts to recoup his fortune by marrying a wealthy one-eyed crone. His mistress, carrying his illegitimate child and helped by her furious mother, is trying to force her way inside to stop the ceremony. The church looks dreadfully decrepit here, and Hogarth shows why: a prominent feature in the left foreground of the painting is a fine big spider's web over the collection box — the spider itself having been dislodged when the box was rifled by the overseer. Hard as it is to imagine now, this was still a positively rural area, and Hogarth was commenting on the general plight of such country churches at the time.

The Third and Fourth (Present) Parish Churches

(a) The new (fourth) parish church on the nearby site of Marylebone Road, opposite York Gate, in the late nineteenth century. Source: Clinch, frontispiece. (b) The church today from York Gate, its imposing portico rising above the busy traffic. (c) The present church's two-tier turret with small cupola supported by gilded carytids.

A close look at Hogarth's painting also gives us a view of a pew panel now to be found in today's parish church. Monuments too were handed down. However, another church was built before the one we see today. In 1740-41 a third parish church was built to replace the second one, on the same site. Although this too was far from grand, the increasing importance of the area can be gauged by a selection of the many well-known figures associated with it. At this third parish church, or in its churchyard, the important architect James Gibbs was buried in 1754; the dramatist and architect Richard Brinsley Sheridan married the beautiful Elizabeth Ann Linley (after an earlier elopement) on 13 April 1772; and Lord Byron was baptised on 29 February 1788. In the same year, the hymnologist Charles Wesley was buried here, and in 1801 and 1806 respectively, the painters Francis Wheatley, best known for his Cries of London series, and George Stubbs, famous for his paintings of horses, were also buried here. The memorial park which marks the site has a board listing a number of other "notable people" laid to rest in the churchyard.

But this church too soon proved inadequate. Clearly, it no longer served a rural parish. Indeed, the parish's population was now estimated to be at least 70,000 souls (Clinch 20). At last, the foundation stone of a new church, close by this older one but on the Marylebone Road (itself built only in 1757, and still called the New Road) was laid in 1813. The structure was originally expected to be a modest chapel of ease, simply as a stop gap (see "A History..."). The parish church itself was to be built in a commanding position in Portland Place, closer to Regent's Park. However, at the last minute, with the "chapel" already well on the way to completion, the plan was changed: this was to be the new parish church after all. A much more splendid edifice was required:

The principal front, next to the New Road, underwent a very important change, a more extended portico and a steeple were substituted for the former design (which consisted of an Ionic portico of two columns, surmounted by a group of figures and a cupola); and other alterations were made in order to give the edifice an appearance more in harmony with the character of a church. [Clinch 21]

The architect of this fourth parish church, a building that would appropriately symbolise the expanding and well-to-do West End, and that would serve parishioners not only from the Portland estate but also as far away as St John’s Wood, was Thomas Hardwick. Hardwick had the right background for the task. He had been a pupil of William Chambers, and had assisted him in the designing of Somerset House. Not without some recourse to Chambers's earlier, abandoned plan for the church, he produced a more imposing structure, still dedicated to St Mary the Virgin. It was completed in 1816 and consecrated on 4 February 1817. With John Nash's subsequent decision to make the York Gate entrance to Regent's Park come out directly in front of it, the building gained as much prominence as earlier church planners could have wished. It deserved such prominence: by 1821 the parish it served would have 96,000 inhabitants (Cherry and Pevsner 593).

Interior: Collins and Dickens

Two views of the church looking east. Left: Interior of the church in 1883, just before the Victorian alterations. Right: The interior as it is today.

Less than three weeks after the fourth church was consecrated, and before it was even completed, it was the setting for Sir Stamford Raffles's wedding to his second wife, Sophia Hull on 22 February 1817. Several years later, Wilkie Collins, whose family lived in New Cavendish Street, which crosses Portland Place, was christened here on 18 February 1824. His biographer Andrew Lycett adds that the church "would later become the local, if seldom frequented, church of Wilkie Collins's friend Charles Dickens, when he lived in Devonshire Terrace" (22), right next to it.

Indeed, Dickens lived at neighbouring 1 Devonshire Terrace for about twelve years, from 1839 to 1851. His fourth child Walter was christened at the church on 4 December 1841, and he took elements of the interior for the christening scene in Dombey and Son, which he started in 1846. His description of it is very bleak, making a "cold and dismal scene" reflecting the particular circumstances of the infant whose mother had died after childbirth, and whose father was "cold and dismal" too. But it is also accurate for its time. Preparations for burials, such as black tressels, shovels and ropes are on view, and everything seems to glower ominously on the ceremony (see Chapter V). Fortunately, much has changed since then, and not only as regards the display of burial equipment: the font, which dates from Georgian times, has been moved to the back of the north aisle, the old shrouded fittings have been replaced with marble ones, and, most important of all, the upper galleries have been removed, so that they no longer mount in shadows to the roof. Unobscured, the large windows now shed light on the interior, making it look bright, cheerful and welcoming. These improvements were all made in the late Victorian period.

The Brownings

Left to right: (a) The altar in front of which the Brownings took their vows. (b) The Browning stained glass window. (c) Bronze bas-relief of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, by Nicholas Dimbleby.

The church's most prominent and poignant literary association, however, is with the Brownings, since Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett slipped in on 12 September 1846 and were married clandestinely here. The nervous invalid was so overcome that she was unable to support herself on the way to the church, though it was so close by, and the newly-weds parted company immediately after the brief ceremony, eloping to Florence a week later (see Forster, Ch. 11). "All the world knows the story," says one historian, adding something perhaps not so well known, that "Robert returned to this church on every possible anniversary of the wedding day, and (it is said) kissed the the step" (Mee 539).

The altar at which the couple took their vows was housed for years in St Giles-in-the-Fields on St Giles High Street, but was returned in 2012, and again stands in front of Benjamin West's recently restored painting of 1818, The Holy Family, as it would have done then. A memorial window to the event, the gift of the Browning Society of Winnipeg, was installed in 1956, and in 2006 Nicholas Dimbleby fulfilled the church's commission to make the bas-relief of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, a lovely companion piece to the nineteenth-century bas-relief of Robert Browning already displayed here. This part of the church, at the top of the north aisle, is called the Holy Family Chapel (see A Short History, n.p.).

Changes in the later Victorian Period

Left to right: (a) Carved mahogany angel playing a trumpet, at the end of a choir-stall. At the other end is an angel playing a harp, and on the wall can be seen the Crucifixion mosaic over the high altar. (b) Apse frescoes of Christ in Majesty by John Crompton. (c) Another mahogany angel on the choir-stall at the south side.

The east end of the church originally had a large painted window, or transparency, the work of the celebrated artist Benjamin West. It depicted the angels bringing the good tidings to the shepherds. However, it had not been admired, and had been removed even before the structural changes of the later nineteenth century. Improvements to the fittings, however welcome, were minor compared to these. The architect in charge was Thomas "Victorian" Harris (1830-1900), author of Victorian Architecture (1860), and one of the so-called Rogue Gothicists of the 1860s who had tried to put their own stamp on the style when it was at its most popular (see Dixon and Muthesius 24). Now he was willing to resist or mix historical elements in a different way. The east wall was removed, a foundation stone laid by Mrs Gladstone herself in 1884, and an arch, full chancel and sanctuary added. This was in keeping with the late Victorian Byzantine Revival, rather than the Regency period when the rest of the church was built. An apse was duly introduced for the sanctuary, and enriched with frescos and mosaic work. The semi-dome was painted, typically enough, with Christ in Majesty, surrounded by the heavenly hosts, with the evangelists and the gospel-writers below. The artist was the landscape and figure painter John Crompton (1854-1927), who became Principal of Heatherley's School of Art in Chelsea from 1888 to 1908 (see "John Crompton").

The church's own website tells us that at this time too the choir-stalls, with their angel carvings, were installed (A Short History, n.p.). Again, this was typical of the time: the Byzantine Revival gave good opportunities to those involved with the Arts and Crafts movement (see Sladen 81). It is worth noting that the distinguished history painter, Edward Armitage, was another of the respected artists commissioned for work in the newly extended church: his contribution consisted of "six life-size wall paintings, between the nave windows, dating from about 1886," and showing "Noah, Isaiah, David, the Virgin Mary, Christ and St John the Baptist" (Armitage). These must have been spectacular, giving a refreshingly new look to a building with a long proud history. Unfortunately, Armitage's frescoes were painted over during repairs to the fabric after damage in World War II. Only with the redecoration of the nave walls and ceiling in 1977 were the nave and apse "ingeniously harmonised" again ("A History of St Marylebone Parish Church").

The splendid twentieth-century (Austrian) Reiger organ at the west of the church, very different from the original "grim" one at the east end that Dickens describes.

Related Material

- Photograph of the "Browning" altar, when it was at St Giles-in-the Fields

- The Relationship of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning

- The Brownings in Florence

Sources

"Architectural Details." St Marylebone Parish Church. Web. 1 August 2015.

Armitage, Jill. In correspondence with the author. Please see her book, published after this page was first written: Edward Armitage RA: Battles in the Victorian Art World (Leicester: Matador, 2017).

"The Browning Room, St Marylebone Parish Church." St Marylebone Parish Church. Web. 1 August 2015.

Cherry, Bridget, and Nikolaus Pevsner. London 3: North West. The Buildings of England. London: Penguin, 1991.

Clinch, George. Marylebone and St. Pancras: Their History, Celebrities, Buildings, and Institutions. London: Truslove & Shirley, 1890. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Library of the University of Michigan. Web. 1 August 2015.

"Famous People Associated with St Marylebone Church." St Marylebone Parish Church. Web. 1 August 2015.

Forster, Margaret. Elizabeth Barrett Browning. London: Random House (ebook), 2012.

"A History of St Marylebone Parish Church." St Marylebone Parish Church. Web. 1 August 2015.

"John Crompton (1854-1927)." Art UK. Web. 4 October 2019.

Lycett, Andrew. Wilkie Collins: A Life of Sensation. London: Hutchinson, 213. [Review]

Mee, Arthur. London: Heart of the Empire and Wonder of the World. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1937.

St Marylebone Parish Church (main page with drop-down boxes to all contents, and search tool). Web. 1 August 2015.

St Marylebone Parish Church: A Short History. Available at the church.

Sladen, Teresa. "Byzantium in the Chancel: Surface Decoration and the Church Interior." In Churches 1870-1914, the Victorian Society's journal, Studies in Victorian Architecture & Design. Vol. III. 2011. 81-99.

Last modified 4 October 2019