avid Mocatta (1806–1882) was born into a well-established, wealthy and philanthropic Sephardic Jewish family — "one of the first Jewish families in the land.... an historic family, too, of extraordinarily wide and important ramifications" (Cardozo 122). Indeed, he could hardly have been better connected in the Jewish community. His father Moses Mocatta was a bullion-dealer who retired early to devote himself to scholarly and philanthropic pursuits; and his first cousin was the very well-known and equally highly respected philanthropist Sir Moses Montefiore. After evincing an ability and enthusiasm for draughtsmanship, and studying under Sir John Soane in London from 1821 to 1827, David Mocatta made forays to Italy and elsewhere in Europe to study and absorb architectural styles, showing some of his paintings from his travels at the Royal Academy in 1831-32. He was a talented watercolourist as well as being keenly observant.

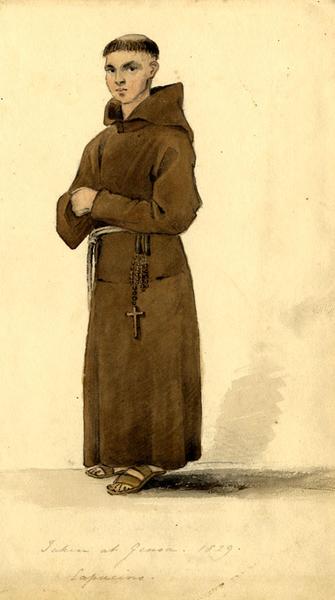

Three of Mocatta's watercolours. Left to right: (a) "Capuchin Friar, Genoe 1829." (b) "Boats with Lateen Sails, Palermo." (c) "Père La Chaise, Tomb of Eloise and Abelard, 1829." Images courtesy Somerset & Wood Fine Art Ltd (see also bibliography).

Mocatta's first big solo commission came in 1831, when he designed a synagogue in Ramsgate for his cousin Moses Montefiore. It was possibly the first to have been designed in England by a Jewish architect: the first stone was laid on 1 August 1831 (see Montefiore 84). It is a refined, unostentatious building with a handsome interior. Mocatta was now attracting attention: he was elected one of the first Fellows of the Institute of British Architects (later the RIBA) in 1837, and would eventually become its vice-president. In 1839, while operating from premises in Brunswick Square, he was appointed architect to the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway, for which he did much of his subsequent work — he designed Brighton Station, the original London Bridge Station, and a series of intermediate railway stations for the line. According to Jack Simmons, there were thirteen stations in all, although other sources llist fewer, and drawings for only seven survive (see Vaughan). It is unfortunate that only Brighton Station remains now, especially as the other stations were in various styles, Horley, for example, being in Tudor Gothic (see Dixon and Muthesius 99; Vaughan agrees that it had a "Tudor feel"). Even at Brighton, his work was soon obscured by later additions, especially in the 1880s. The plans show, however, that in all cases Mocatta "gave careful thought to evolving designs that should be economical, functionally sound, and comfortable for passengers" (Simmons 33). Still to be seen on te line, and still in constant use, is the Ouse Valley Viaduct in Sussex, on which he collaborated with the company's engineer, John Urpeth Rastrick, adding the architectural features, notably balustrades and Italianate pavilions, that give it its distinctive appearance. This is felt by many to be his greatest achievement.

Mocatta moved his practice to Old Broad Street, in the City, in 1846. By then he had already designed temporary premises for the West London Synagogue of British Jews, of which he was a founder member, and he now designed a more permanent building for it in Margaret Street, which was duly dedicated in 1849. In the construction of this, he was said to have displayed "exquisite judgement" (The Standard, 26 June 1849). Unfortunately, this too would be lost. It was replaced in his own lifetime by a new and more capacious synagogue, built for the congregation in Upper Berkley Street and opened in 1872.

Well before that Mocatta had inherited his family fortune, and had resigned, as his father had done, to devote himself to philanthropic pursuits. He interested himself in hospitals — for example, he was on the board of University College Hospital, London — and he also became Senior Trustee of the Soane Museum, a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, and chairman of the council of the West London Synagogue, as well as being active on behalf of the Architects' Benevolent Society, and in the struggle for Jewish parliamentary emancipation. He died at his home in Kensington on 1 May 1882, notice of his death appearing in the Times three days later (p.1), to be followed by "In memoriam" notices in subsequent years. He is remembered in Brighton not only by the station, but also by nearby Mocatta House, much changed from his original design, and now used as serviced offices. — Jacqueline Banerjee.

Works

Bibliography

"About the Synagogue at Ramsgate." Montefiore Endowment. Web. 9 June 2018.

Bradbury, Oliver. Sir John Soane's Influence on Architecture from 1791: A Continuing Legacy. Farnham: Ashgate, 2015.

British Library Newspapers. Web. 9 June 2018.

Cardozo, David Abraham Jessurun. Synagogue and College, Ramsgate, 1833-1933. From the Dedication of the Synagogue to the Death of Sir Moses Montefiore, Bart., 1833-1885. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1933.

"David Mocatta, 1806-1882." Somerset & Wood Fine Art Company (— this has a wonderful collection of Mocatta's watercolours, and a whole range of paintings by other nineteenth-century artists as well). Web. 9 June 2018.

Jacobs, Joseph, Isidore Harris and Goodman Lipkind. "Mocatta." JewishEncyclopedia.com. Web. 9 June 2018.

Montefiore, Moses, and Judith Cohen Montefiore. Diaries of Sir Moses and Lady Montefiore: comprising their life and work as recorded in their diaries from 1812 to 1883. Ed. Louis Loewe. Chicago: Belford-Clarke Co., 1890. Internet Archive. Contributed by University of California Libraries. Web. 9 June 2018.

Orbell, John. "Mocatta family (per. 1671–1957)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 9 June 2018.

Simmons, Jack. The Victorian Railway Station. Pbk ed. London: Thames & Hudson, 1995.

Times Digital Archive. Web. 9 June 2018.

Vaughan, Adrian. "Mocatta, David Alfred (1806–1882), architect." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 9 June 2018.

"View of the Brighton Station." Wikimedia. Web. 6 April 2015 (appears in a review of Bradbury, see above).

Created 9 June 2018