harles Parker (1799-1881) trained under Sir Jeffry Wyattville and studied drawing with George Maddox (1760-1843). His subsequent travels in Italy inspired his lifelong interest in Italianate design, especially for private houses: his influential Villa Rustica selected from the buildings and scenes in the vicinity of Rome and Florence, and arranged for rural and domestic dwellings; with plans and details came out in sixteen monthly parts from 1832 onwards and was published in a second edition in 1848. It gave helpful, practical advice on adapting Italian ideas about residential architecture to the English climate and general context. As he put it in introducing Plates XLVI-LII,

As practised by the great masters, it is varied in its general outline and simple in its component details; and, by combining all the elegances and conveniences of modern life, it is rendered applicable to the habits of their own as well as this country. From the character of the several parts, all the ordinary comforts that form and are indispensable to a residence for the upper classes can be preserved, and at any time increased, without allowing any one portion of the building to assume too much importance, or lose the peculiar features of Rural Architecture.

In short, an English home could be designed along Italian lines to be well-proportioned, elegant and appropriate to its local setting. Parker's architectural pattern book was not the first or even main inspiration for the adoption of Italianate features. The style was pioneered by John Nash (for example in this Park Village house by Regent's Park), and Sir Charles Barry (for example, in his 1830s' remodelling of Kingston Lacy), and indeed such pattern books began to proliferate. But Helen C. Long tells us that the book was nevertheless a "key source for the Rural Vernacular style so popular with housebuilders all over Britain" (31). Since the work began to appear during the first surge of construction in this boom time for speculative suburban building, its influence cannot be overstated. The fact that Thomas Cubitt owned a copy of the book, which may have influenced the design of Osborne House for the royal family on the Isle of Wight (Long 32), speaks volumes.

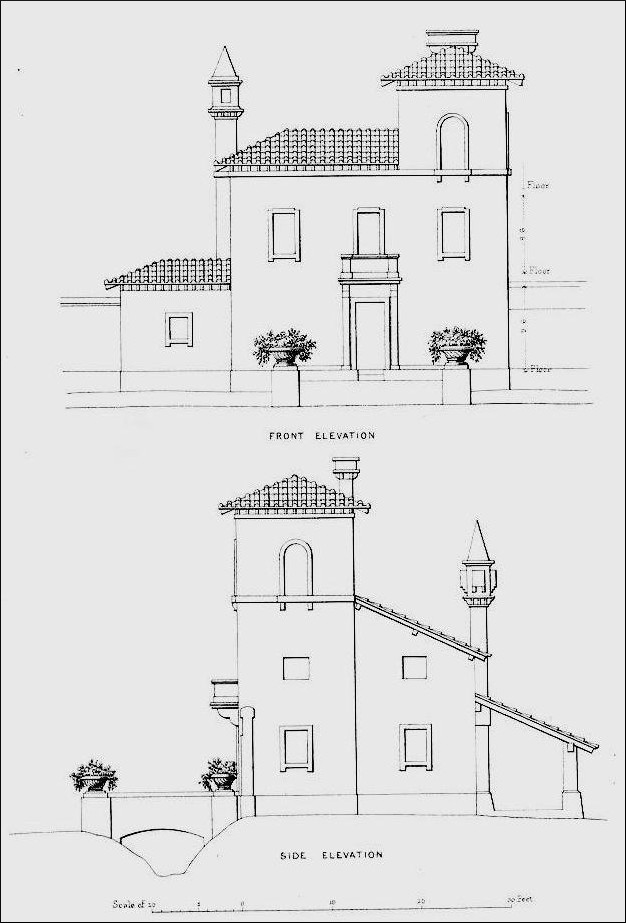

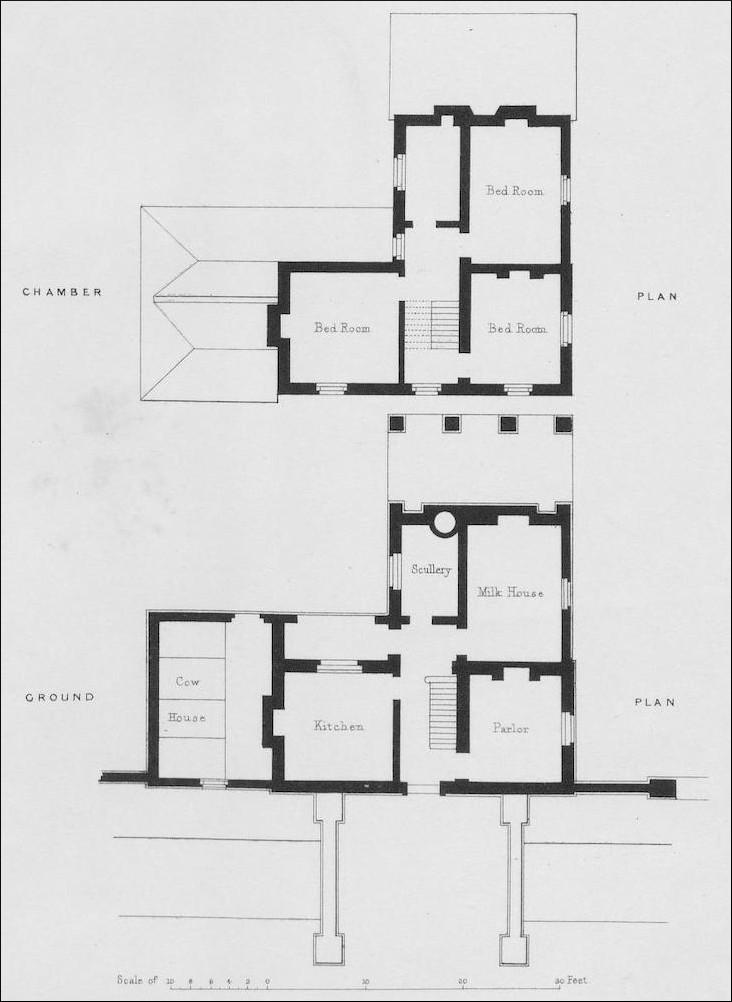

One of Parker's examples: a house in the Via Ostiense in Rome, among those often occupied by husbandmen, in which space is given downstairs to diary, cattle-shed etc, which could, of course, be used for other purposes. Parker estimates the outlay for a stone building on this plan to to be £520. Source: Parker, Plates XVII-XIX.

Parker was in every way a good spokesman for the Italianate style. In the early 1830s, he had established himself in London, becoming one of the very first fellows of the Institute of British Architects in late 1834, before the institute had been granted the prefix, "Royal." His address as given then was 16 Tavistock Street, Bedford Square. He was active in the institute, reading papers there regularly: for example, The Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal carried extracts of a paper he read to members on "Cast Iron Bearers," on 15 January 1837. At this time he was also involved with the Royal Society of Antiquaries, remaining a fellow of it for ten years, up to 1844.

Among Parker's works were the new building for Hoare's Bank at 37 Fleet Street, designed very early in his career (c.1829–1830); the portico to the Hoares' magnficent country estate at Stourhead (though guided by earlier plans for the house) for Sir Hugh Hoare (1840); the tower of Kimpton church, Hampshire (1837–8); and the beautiful Italianate church of St Raphael in Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey (1846–47). He also altered the Spanish Chapel in Manchester Square (1846, later demolished). According to M.A. Goodall, he was "steward and surveyor to the duke of Bedford's London property from 1859 to 1869," which must have provided a steady income as well as prestige. Later, in and from the 1870s, the Italiante style for domestic residences was overtaken in popularity by the Queen Anne style.

Parker was married to Mary Lucy Parker (née Molteno). He retired in 1869, his retirement from RIBA having been announced in the Building News of 19 November that year ("Royal Institute of British Architects," 387). He had problems with his eyesight, and at some point became entirely blind. He died on 9 February 1881 at the age of eighty-one, at his home, 48 Park Road, Haverstock Hill, leaving four daughters. Parker was buried in the churchyard of St Thomas of Canterbury's R.C. Church, Fulham (interestingly, and perhaps ironically, built in the competing Gothic Revival style by A.W.N. Pugin).

Works

- Hoare's Bank, Fleet Street

- St Raphael's R.C. Church, Kingston-upon-Thames

- Stourhead House, Wiltshire, showing the portico added under Parker's supervision

Bibliography

Brodie, Antonia. Directory of British Architects 1834-1914. Vol. II, L-Z. London: Continuum, 2001. 317.

"Cast-Iron Girders." The Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal. Ed. William Laxton. Vol. 1 (1837): 106-7.

"Charles Parker." Find a Grave. Web. 9 November 2024. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/121282373/charles-parker

Goodall, M. A. "Parker, Charles (1799-1881)." The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 12 November 2024.

Long, Helen C. Victorian Houses and Their Details: The Role of Architectural Publications in Their Building and Decoration. Oxford: Architectural Press, 2002.

Nairn, Ian and Nikolaus Pevsner, Nikolaus. The Buildings of England: Surrey. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2nd ed. 1971.

Parker, Charles. Villa Rustica selected from the buildings and scenes in the vicinity of Rome and Florence, and arranged for rural and domestic dwellings; with plans and details. London: John Weale, 1848. Internet Archive, from a copy in the Miles Lewis Collection. Web. 12 November 2024.

"Royal Institute of British Architects." Building News and Engineering Journal. Vol. 17. 2 (1869): 387-88. HathiTrust, from a copy in the University of Illinois Library. Web. 12 November 2024.

Created 12 November 2024