Photographs by the author. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on all images for larger pictures.]

"A seminal building in the history of C19 church architecture..... E.E. style and memorable as a very early case of the archeologically convincing church" (Hartwell 324).

Exterior

St Wilfrid's Church, Hulme, west front with north elevation stretching back. Listed Building. Augustus Welby Pugin (1812-1852), with George Myers (builder), and additions by E. W. Pugin. 1842 (additions in the 1860s). "Red brick in English bond, with sandstone dressings and slate roof" ("Roman Catholic Church of St Wilfrid Manchester"). Birchvale Close, Hulme, Manchester.

The west end of this church is uncompromising in its bold lines. Its expanse of brickwork is hardly interrupted by its narrow windows and humble west door, but it does feature sturdy flat buttresses rising almost to the roof on either side of the entrance, and sandstone ledges below — and drawing the eye to — recesses. One is reminded of Kenneth Clark's adjectives for Pugin's roughly contemporaneous Mount St Bernard Abbey in Leicestershire: "stark" and "solid" (119). A tower was planned at the north-west corner, rising from the square block on the left, above the door there. This would have balanced the whole, though in a picturesque, asymmetrical fashion (see Pugin's drawing of it). As for having the tower off-centre, he himself explained that "the ancient designers" were not concerned with uniformity. Rather, "they regulated their plans and designs by localities and circumstances; they made them essentially convenient and suitable to the required purpose, and decorated them afterwards" (22). In particular, "[a] tower, if the locality require it, may be built on one side or corner of a church, without any obligation of building up another opposite" (23). Whether or not he was "thinking as he wrote" here (Hill 252), to justify his design, it is true that a completed tower would have have produced a more pleasing composition. But even as it is, the outside of the church, like most of Pugin's work, makes a big impact.

Left: West entrance. Right: South elevation (taken above rows of parked cars).

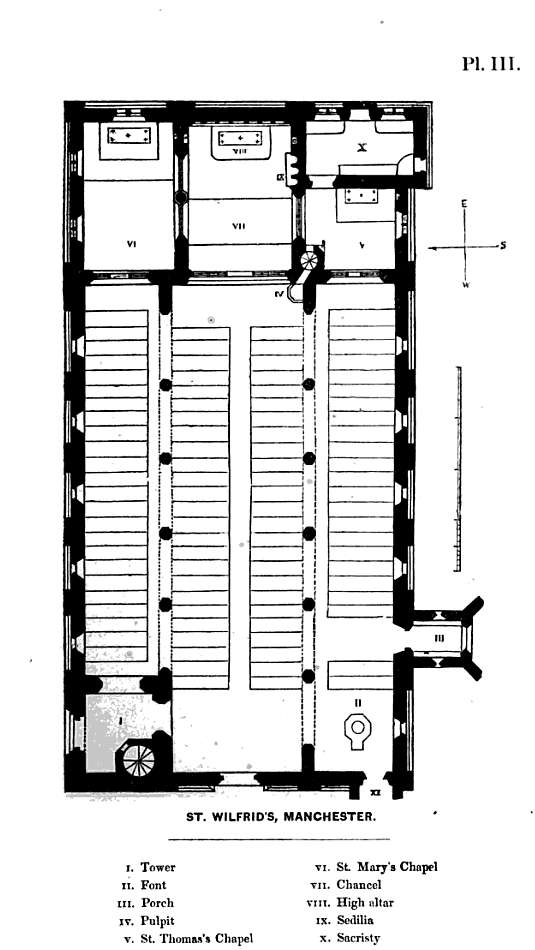

Apart from the porch at the west end, the projecting parts were by Edward Pugin: three gabled confessionals off the south aisle, and an extended sacristy. See internal plan below for the original design, which was very (and literally) straightforward. As for the view from this angle, Clare Hartwell puts it nicely: "The parts are separately expressed, with low roofs clustering about the body of the church" (324) — exactly the same as can be said for Pugin's house, The Grange at Ramsgate (see the last caption and paragraph there).

Left to right: (a) Gabled confessionals, with quatrefoils and lancets, the latter now covered with wire netting, by E. W. Pugin. (b) Plan of the church (from Pugin, Plate III), its rectangular lines broken only by the south porch and slightly projecting sacristy. (c) The wheel window and three simple lancet windows, without tracery, at the east end.

Unfortunately, additions soon hid the buttressing along the south elevation shown in the plan of the church. It can be seen most clearly just to the left of the sacristy, and rising on either side of the east windows (above right). "Pugin delights in setting back the wall surfaces and expressing points of tension ... with flat buttresses" (Hartwell 325). St Wilfrid's was a capacious but modest building for what was then a rural area on the outskirts of Manchester: "For some years after St. Wilfrid's had been opened in 1842, it was known as St. Wilfrid's in the Fields. There were many complaints that it was built too far into the country.... Before long the position of the new church was fully justified. In 1843 there were 237 infant baptisms. In five years this figure had increased to more than 500. In 1850 there must have been more than 12,000 people in the new parish" (Sullivan).

Interior

Left to right: (a) Panelled roof and wheel window above the chancel. (b) Close-up of the wheel window, which has faded and looks insipid now. (c) The east window lancets.

The church, which was deconsecrated in 1990, is now partitioned into offices, and a canopy covers part of the chancel, making it impossible to do more than snatch glimpses of its past beauty. But even those glimpses are impressive. Pugin certainly "decorated [it] afterwards," as he said those "ancient designers" did, and as he himself believed to be appropriate for a house of worship. Again, Hartwell says it best: "There is a complicated queen-post roof of domestic rather than ecclesiastical inspiration" (325-56), though the listing text is more technical: "elegantly slender collared queen-post trusses with unusual linking purlins arch-braced from these posts, and arch braces from wall-posts to tie-beams, all these members with painted small chamfer."

As for the stained glass, there is evidence that Pugin himself designed windows for the church in 1845, to be executed by William Wailes (see Shepherd 266 and 415). But there was some problem here. According to Eastlake,

The chancel of St Wilfrid's was found to be very dark, and some time after its erection enquiry was made of him, as the architect of the church, whether there would be any objection to introduce a small skylight in its roof, just behind the chancel arch, where it would be serviceable without obtruding on the design. Pugin sternly refused to sanction — even on these conciliatory terms — the adoption of any such plan, which he declared would have the effect of reducing his sanctuary to the level of a Manchester warehouse. (160)

At any rate, the present windows are nothing like (for example) the east window lancets of Pugin's chapel at the Grange (1844, also by Wailes), and Hartwell says they were put in later, the top one dating from about 1880, and the lancets from between the world wars, the latter having been made by the Dublin firm of Harry Clarke & Co. (326).

Left to right: (a) Arcade behind the altar, with lovely mosaic work. (b) Statue of the Virgin Mary in a niche at the edge of the chancel. (c) Attractive tiling in the chancel.

See Pugin's sketch of the chancel for the wider setting. The motifs at the top of the arcade represent aspects of the Passion. Shown here are a twined (and, on close inspection, prickly) circle representing the crown of thorns; a ladder representing the crucifixion, along with the sponge dipped in vinegar, and the spear that pierced Jesus' side; and a garment and dice, recalling the casting of lots for Jesus' clothes. As for the statue of the Virgin Mary, whilst similar in general, and apparently dating from the 1850s, this is far less elaborate and distinctive than the similarly placed one at Our Ladye Star of the Sea in Greenwich. Hartwell is surely right to call it "Puginesque" rather than Pugin's (326). The figure could possibly be "that French image of the blessed Virgin" that Pugin complained about to his patron Lord Shrewsbury, in the context of some figures acquired at second hand after having been removed from the Earl's chapel: "I will never advise sending anything to bazaars again ... I thought I had seen the last of them and they actually go into a church [St Wilfrid's] that should be perfect in its way" (letter reproduced in Ferrey 132).

Other details: Left: Border pattern in the mosaic tiling. (b) Stencilling at the top of a column in what is now a narrow corridor.

St Wilfrid's gave Pugin some grief even in his own day. This was because a large school was going up beside it: "On the side next to Rutland-street, there is a large school now in progress of erection, of a style of architecture corresponding with that of the church, according to designs given by W. W. Wardell, Esq. of London" (qtd. in Sullivan). What bothered Pugin was that the job had been given to someone else. "I think I am about the most mad [?] man in England.... There is no justice I have just been one [?] to batter down the wall for other people to walk in," he complained bitterly (qtd. in Shepherd 86) Wardell was a disciple of his. The two had even worked on the same churches (notably, Our Ladye Star of the Sea, mentioned above). But it was galling for Pugin to be superseded in this way. No doubt he would have been even more upset to see the church looking so dilapidated today. The only consolation is that it still stands, allowing us to see traces, even now, of what once made its interior "the richest specimen of polychromatic painting in England" (contemporary newspaper account, qtd. in Shepherd 266).

Related Material

- "Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin" (by Charles Eastlake)

- "A Marvellous Man" (Review of Rosemary Hill's God's Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain)

- The Church Tower (Pugin's discussion)

- The Appropriate Scale and Decoration of Churches (Pugin's justification of splendid interiors)

References

Clark, Kenneth. The Gothic Revival. Harmondsworth: Penguin (Pelican), 1964. Print.

Eastlake, Charles L. A History of the Gothic Revival. London: Longmans, Green, 1872. Internet Archive. Web 8 June 2012.

Ferrey, Benjamin. Recollections of A. N. Welby Pugin, and his father Augustus Pugin; with Notices of Their Works. London: Edward Stanford, 1861. Google Books. Web. 8 June 2012.

Hartwell, Clare. Manchester (Pevsner Architectural Guides). London: Penguin, 2001. Print.

Hill, Rosemary. God's Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain. London: Penguin, 2008. Print.

Pugin, A. Welby. The Present State of Ecclesiastical Architecture in England. London: Charles Dolman, 1843. Google Books. Web. 8 June 2012.

"Roman Catholic Church of St. Wilfrid Manchester." British Listed Buildings. Web. 8 June 2012.

Shepherd, Stanley A. The Stained Glass of A. W. N. Pugin. Reading: Spire Books, 2009 (see especially the Gazetteer, pp. 266-67). Print.

Sullivan, John B. "St Wilfrid's R. C. Church, Hulme, Manchester.". sullivanweb. Web. 8 June 2012.

Last modified 29 January 2013