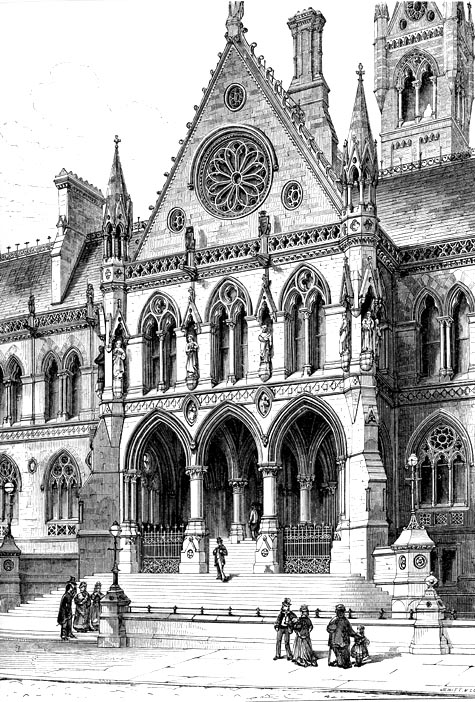

Entrance

Alfred Waterhouse (1830-1905)

1859-64

Assize Courts, Manchester

Eastlake, facing p. 312

The Manchester Assize Courts: conipetition attracted more than a hundred candidates, among whom were many whose names had been little known before, but who have since become eminent in their profession. The choice of the judges fell upon Mr. Alfred Waterhouse, a local architect, who had sent in a Mediaeval design, which united considerable artistic merit with unusual advantages in regard to plan and internal arrangement. [Eastlake's commentary contined below]

Photograph and caption by George P. Landow

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Commentary by Charles L. Eastlake

The original treatment of its individual features did not indeed indicate evidence of a thorough and consistent attempt to realise in this building the character of any special phase or type of Gothic art. The formal proportions of its principal façade the outline of its roof, the fenestration of its upper story, and, above all, the nature of its ornamental details, showed a tendency to depart from the unities of architectural style. At the time of this competition many young architects had devoted themselves with enthusiasm to the study of Early French Gothic, and had really caught much of the spirit of twelfth century work. Others still clung to national traits, an endeavoured to preserve them in their designs. A few had studied the Mediaeval examples in Lombardy and Venice to some profit, while others were allured by the more specious attractions of the Italian Renaissance. Some of these several types were ably represented in the Manchester competition, and perhaps if the decision of the judges had been based on artistic considerations alone, more than one; of the candidates would have taken precedence of Mr. Waterhouse, the principle of whose design was confessedly eclectic. But experience has proved that whatever may be accomplished in ecclesiastical or domestic architecture, the special characteristics of individual style can rarely be renewed in their integrity for modern public buildings without some sacrifice of convenience, and that is precisely the requisite which those who have the management of public buildings are bound to secure.

Time has shown that Mr. Waterhouse's plan for the Assize Courts is admirably adapted for its purpose; and, with regard to the artistic merits of the work, it will be time enough to criticise when any better modern structure of its size and style has been raised in this country.

During the interval which elapsed between the selection and execution of his design, Mr. Waterhouse introduced many improvements in the facade. The central block, of which the lower portion is devoted to an entrance porch, had terminated above in a fantastically-shaped roof, surmounted by a clock turret. In place of this feature, a lofty gable, pierced with a large wheel window, is now substituted. The upper windows of the principal front had been enriched with ogival hood mouldings. These were omitted in execution, and the window heads gain immensely in effect by the change. In the Southall Street front other modifications were adopted in the plan, which considerably enhanced the general effect. The best view of the building as a composition is at some little distance from the corner formed by the junction of Great Ducie Street and Southall Street, where the principal masses of the building group excellently together.

The aim of the architect seems to have been to secure general symmetry with variety of detail. Thus the principal facade is exactly divided by the central block: the wings on either side are lighted by exactly the same number of windows, but the windows themselves vary in their tracery. Perhaps the least satisfactory feature in the design at first sight is the lofty tower, which, rising in the centre from the rear of the building, looks like an Italian campanile, but really serves the purpose of a ventilating shaft. Yet, after the eye has become accustomed to its proportions, there are really no definite faults to find with it but faults of detail, on which it would be hypercritical to enter here. At this stage of his career, and it was a very early stage, Mr. Waterhouse perhaps erred in over-prettifying his work. This tendency may be noticed here and there in the design; but it never lapses into fussiness or descends to vulgarity.

The interior of the great hall is most successful in its proportions. It has an open timber c hammer-beam' roof, and a large pointed window with geometrical tracery, at each end. The doorways leading hence to the corridors and adjoining offices are studied with great care; and indeed the same may be said of every feature in the hall, from its inlaid pavement to the pendant gasaliers. The Civil Court and the Criminal Court (each capable of holding about 800 people) are respectively to the north-east and south-east of the hall. They are identical in size and arrangement, and are provided with the usual retiring rooms for judges and juries,

The barristers' library is a picturesque and effective apartment, with a roof following the outline of a pointed arch, and divided into panels. The barristers' corridor is lighted by a skylight, supported at intervals by arched ribs cusped and slightly decorated with colour. This, together with many other features in the building, represents with more or less success an attempt to invest modern structural requirements with ain artistic character which shall be Mediaeval in motive if not in fact. The trying conditions of this union cannot be too constantly kept in view by critics, who, applying an antiquarian test to such works as this at Manchester, proceed to condemn the association of features for which there is no actual precedent in old and genuine Gothic.

Now it is quite certain that if any modern architect were so ingenious as to be able to raise in the nineteenth century a municipal or any other building, which, in its general arrangement and the character of its details thoroughly realised the fashion of the thirteenth or fourteenth century, it would be about as uncomfortable, unhealthy, and inconvenient a structure as could be devised. There must be a compromise, Gothic architecture under its old conditions, and where the ordinary requirements of life are concerned, is impossible. Gothic architecture under modern conditions — improved methods of lighting and ventilating, sanitary considerations, the use of new materials, and habits of ease and luxury — may be, and indeed is, very possible. But it is open to various interpretations, and in judging of its examples we must apply to them a new standard of taste — a standard of no narrow limit to place or time, artistic rather than archaeological, founded on necessity rather than on sentiment. Judged by such a standard as this^ Mr. Waterhouse's work at Manchester is a decided success.

References

Eastlake, Charles L. A History of the Gothic Revival. London: Longmans, Green; N.Y. Scribner, Welford, 1972. Facing p. 261. [Copy in Brown University's Rockefeller Library]

Victorian

Web

Archi-

tecture

Gothic

Revival

Alfred

Water-

house

Next

Last modified 7 February 2008