In that remarkable English revival of decorative design and handicraft which has taken place during the last five-and-twenty years, the art and craft of the needle hold a distinctive and (listinguished position. Distinctive, I would say, because of the peculiar charm and delicate beauty of needlework among the sister arts of decoration; distinguished, because of the skill, taste, and devotion of individual craftswomen who have raised the standard of accomplishment.

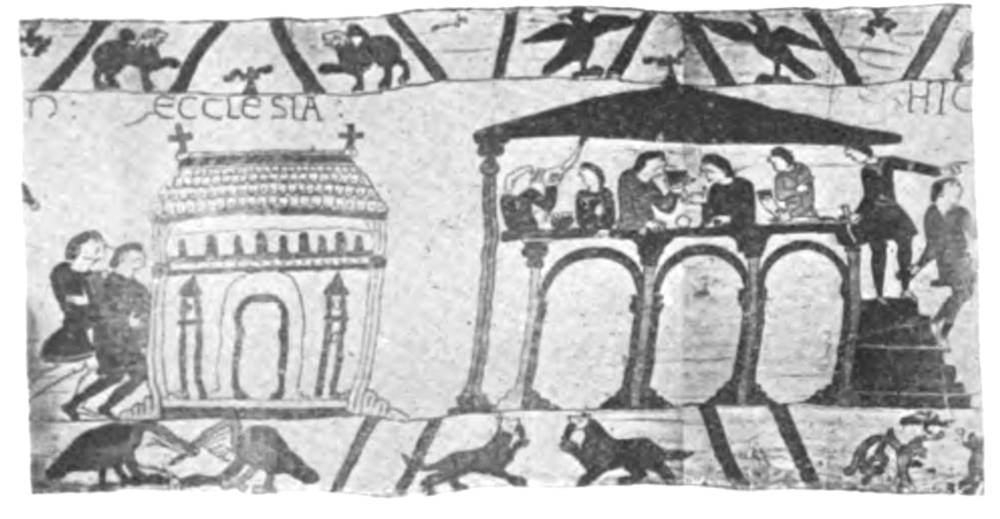

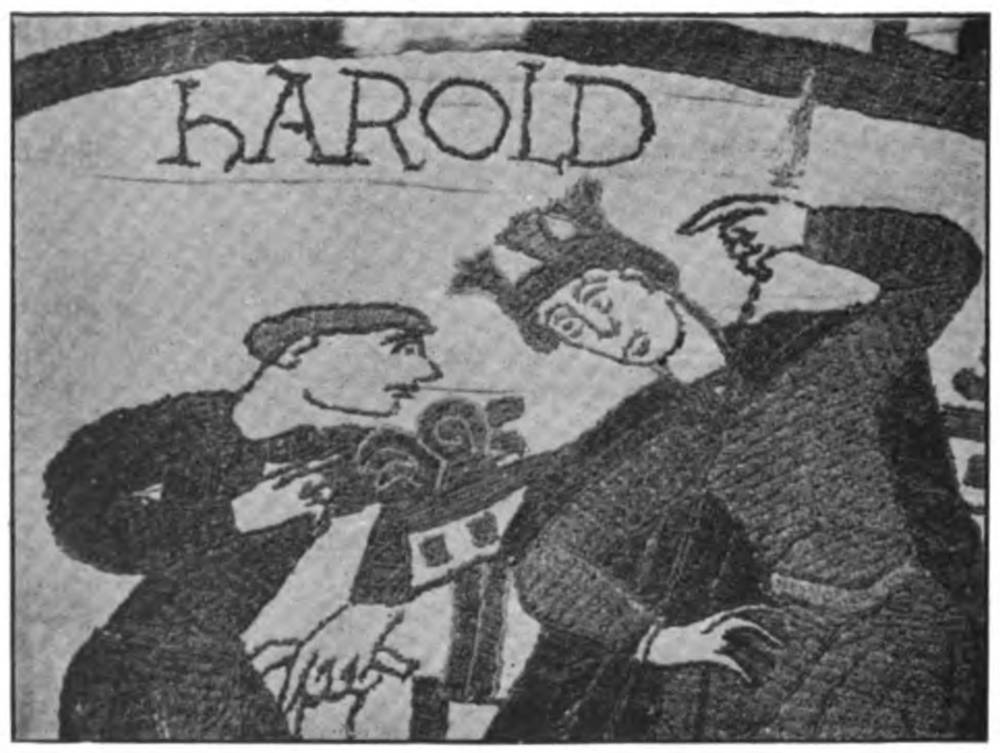

Portion of Bayeux Tapestry. Click on images to enlarge them.

We should have to go back to the early seventies to trace the movement, which seems to have derived early inspiration and practical stimulus, in common with so many of the other arts and handicrafts, from the workshop of the great poet-craftsman we have so lately lost — William Morris — and his colleagues, who may he said to have carried into practical shape the ideas of the great romantic and realist revolt of the mid-nineteenth century, associated, in painting, with the rise and influence of the Pre-Raphaelite school.

Immediately prior to this period the leading kind of what was called “fancy needlework” took the form known as Berlin-wool work, elaborate designs for which were sometimes prepared (like carpet designs) on squared paper. The design was outlined upon a very open kind of canvas, or stiff white net, and worked by means of a cross-stitch which neatly covered each hole of the canvas, square by square, building up — in generally the crudest colours obtainable in dyed wool — the design, which was apt to take the form, after the first geometric essays in chequcrs, of rather emphatically shaded flowers relieved upon positive grounds of black or some dark hue; or even, in its more elaborate phases, of reproductions of some popular painting, undaunted by the mechanical necessity of turning every outline into that of a staircase.

The period was marked by an extensive deposit of slippers — the favourite objects for daring effects of colour, and offering not too arduous a field of work to fair amateurs, while at the same time they afforded a graceful mode. of expressing sentiments of esteem, say, to a popular eeclcsiastic, who, perhaps, might emulate Chaucer's squire, with

“Paula’s windows corvcn on his shoes,”

by designs still more wonderful and fearful. The earlier forms of such work, however, were agreeable enough, as may be seen by an example on page 148 containing the royal arms. The square stitches are, in this case, smaller.

Portion of Bayeux Tapestry.

This was before the formation of industrial art museums like our unrivalled South Kensington. And here let me say, in expressing my obligations to the authorities, who placed every facility in my way as regards illustrating these remarks from their magnificent collection of textiles, that it is impossible to put too high an educational value upon such collections, the only pity being — indeed, I would say it is nothing short of a national reproach — that they cannot yet be properly housed and therefore not properly displayed. It is, I think, not sufficiently realised by the public at large that a museum such as this is really a reference library of examples to the designer and the craftsman of [144/145] incalculable importance and value, and, as such, it bears upon the industries of the whole country.

The cultivation of taste by means of the study of the best examples of old work in such collections and existing in many historic houses in different parts of the country, the charming samplers of our great grandmothers' days, the influence of rich specimens brought from Italy and the East by travellers, or imported by commerce, all these had, no doubt, an important effect in the creation or revival of better ideals and aims in decorative needlework.

Bohemian Shirt Front.

Before the Royal School of Art-Needlework was founded, which has done so much to spread the knowledge of the different methods and applications of the craft, and has offered both training and employment to many workers; from which, also, have sprung so many branches and offshoots, and which is now entering a new existence as a technical school under the Technical Education Board of the London County Council; before these organised efforts in technical instruction and revival, here and there an enthusiastic needlewoman quietly set to work with coloured cottons, or crewels, or silk, to endeavour to give expression to the new-old conception of decorative beauty which not only was capable, in the various forms of its application, of giving a touch of peculiar refinement to the domestic interior and character to dress, but also lent itself to the representation of certain forms and textures, and even to suggestions of poetry and romance.

Indeed, if we look to the past, needlework has been the medium for the record of important historical events, of which the famous so-called “Bayeux tapestry” is an instance. Here we have the history of the events connected with and including the Norman Conquest of Saxon England. It is expressed in a very simple but very direct and dramatic manner. The figures are worked in coloured worsteds upon linen, mostly in a kind of chain-stitch. The design being treated as a continuous pattern, in frieze-form, the subjects are on the same plane, as in picture-writing, leading on without break one to the other; legends in Latin worked clearly upon the linen ground explaining each incident and giving the names of the principal characters, the lettering forming a decorative item in the work. There is no background, and there is an ornamental border of quaint animals, divided by diagonal bands, framing the frieze of subjects above and below. The design has very much the characteristics of the contemporary design of the same period as found in other materials (allowing for differences of adaptation) — as, for instance, carved stonework, illuminated MSS., and mosaic — while showing a certain simplification of treatment adapting it to that form of needlework." [Crane’s footnote: The work — which was said to have been by Matilda, wife of William the Conqueror — is to be seen in the little museum of the quiet and quaint Normandy town, which retains in this piece of needlework and in its noble cathedral the relics of its former historic importance.]

The history of design in needlework, too, shows much the same characteristics and seems to fall under similar influences in the course of its evolution as design generally speaking. We have the common origin of necessity and utility in the primal function of the needles-to join textiles together and to form garments — and in its early forms we find it closely united with weaving. We have the early symbolic period, the picturewriting, the ecclesiastical influence, and we may trace, all along, the purely ornamental feeling influenced by the desire for naturalistic representation, the pictorial influence from the fifteenth century onwards, and this again mingling with the ideas of the classical revival, merged with the later rococo forms, and so on to naturalism again; all these forms or styles now existing side by side in their revived forms, to the confusion of modern taste, struggling to maintain its equilibrium amid such contrasts; albeit, one may be aware of a new spirit — a feeling distinct and modern — asserting itself; derived, it may be, or inspired, from many sources, but with a certain fresh infusion of natural feeling, and a determination towards primitive simplicity of form and arrangement.

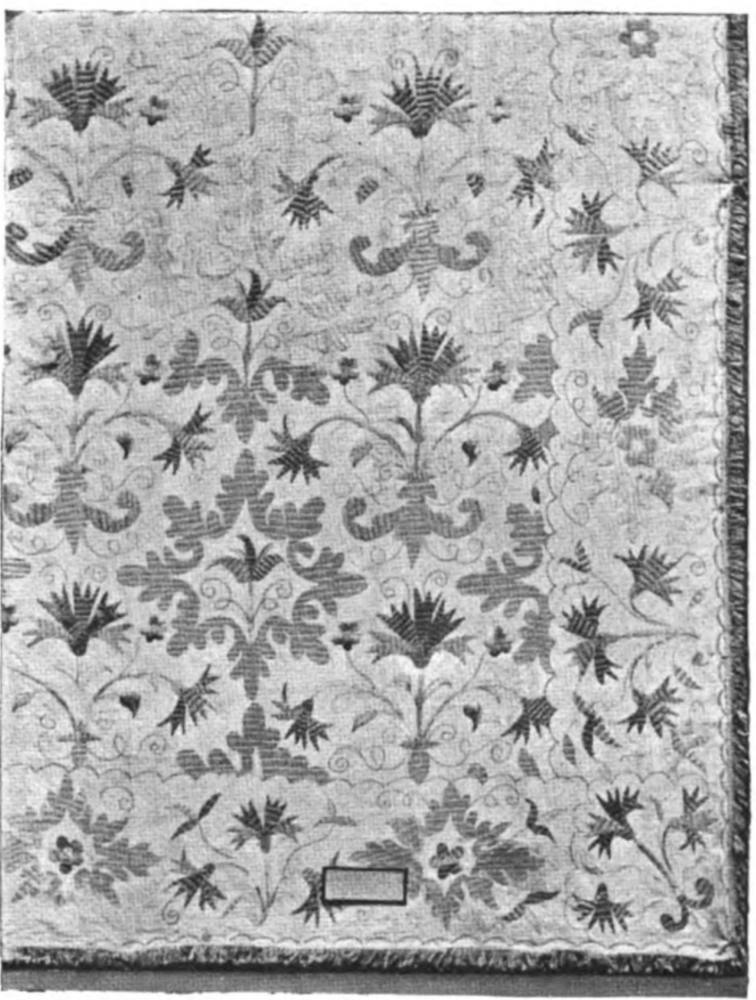

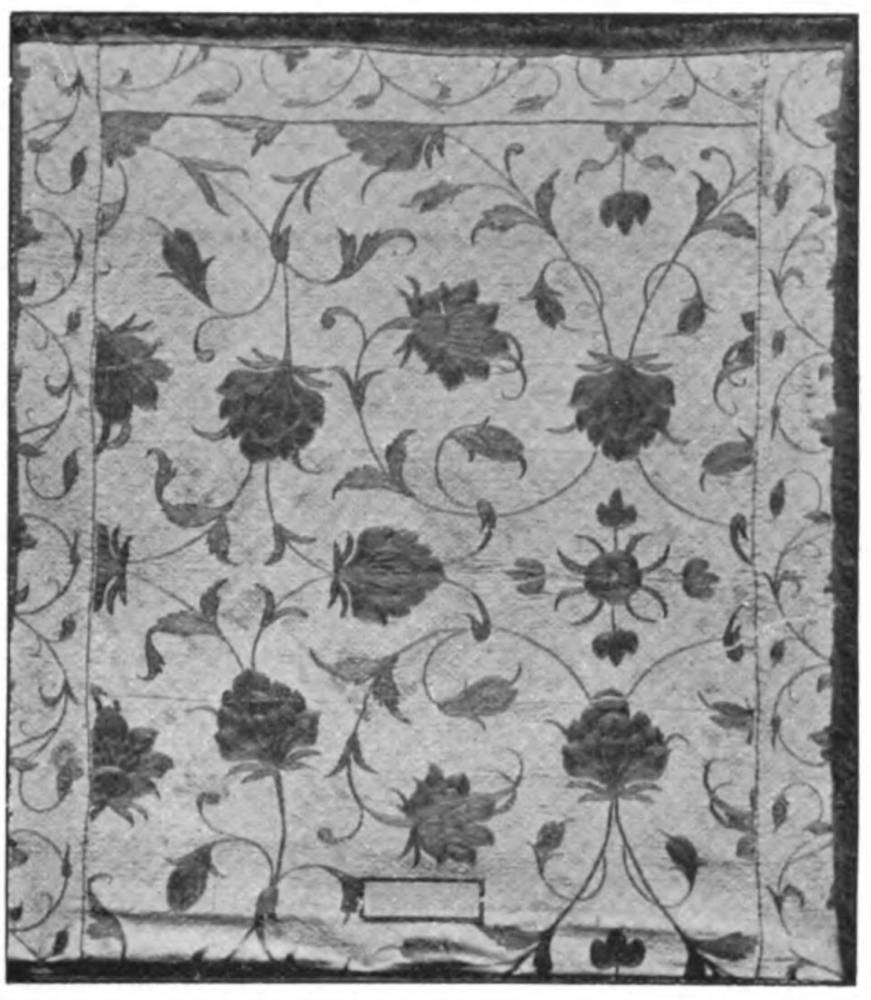

We may trace the origin of decorative needlework, as I have said, in necessity and utility. We may see its traditional forms in the peasant embroidery still surviving in some European countries, in patterns and methods handed down probably from quite early times, and often showing traces of medizeval and Oriental influence. We all know the festa apron of blue or green cloth of the Roman peasant, with its bands of bright worsted embroidery, sometimes heightened by spangles. In parts of Bohemia peasant women still decorate their costumes with embroidery. I sketched a man from the Austin-Hungarian frontier, at Prague, who had his name beautifully worked upon his shirt-front with a floral design in red and yellow thread. The beautiful embroideries of the Cretans are well known; and in travelling in Greece I saw a peasant woman by the wayside cmbroidcring one of those woollen Albanian jackets which are part of the distinctive national costume of the people of modern Greece. The country-women sometimes The East, as the great source of the glowing stream of pattern invention and colour, however, seems to have been the natural home of embroidery from the time of Solomon — who places the art among the occupations of the ideal woman — onwards. Modes of life and habits of the people continuing with but little change, the artistic traditions lntvc been much more permanent. The Persian women, for instance, still work, I believe, beautiful covers, carpets, and hangings for their marriage. The material may be only cotton, but the decorative cfl'ect produced by their large bold patterns of rich red flowers and the serrated green leaves and stems, worked in silk, is extremely fine. In the hangings from Bokhara the Persian feeling is very marked. The pattern is finely distributed over the ground, and the relation of border to field well maintained. They are interesting, too, as illustrating an important principle in floral design, well understood throughout the East, of a controlling shape or enclosure which determines the limits of the sprays — the favourite being the oval, or pine, or palmetto shape — from which the modern designer may learn much. Wear a kind of sleeveless overcoat of wool heavily embroidered or darned with blue, green, and brown worsted, which adds both weight and warmth.

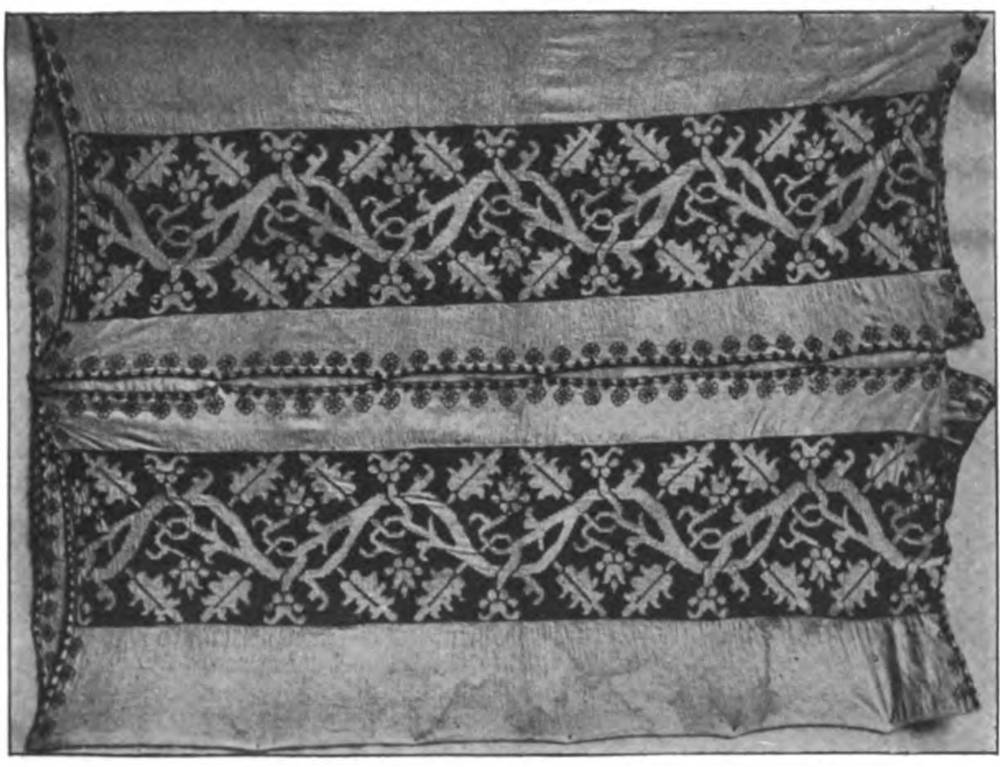

Towel Borders “In the South Kensington Museum.”

There is a form of blouse worn by Russian girls which is decorated by bands of embroidery in bold conventional patterns worked in cross-stitch. 'l'hcse garments are worn by quite young girls, and growth is allowed for by simply. adding on extra rings or bands of embroidery, the garment being sufficiently amply constructed otherwise, and intended to be put on over the head. These cross-stitch borders recall those found on Spanish and Italian linen cloths and towels of sixteenth-century date, of which beautiful specimens are to be found in the Museum. These are worked in red silk, and are generally of a repeating pattern of a woven textile character, which may arise from the pattern having been woven in the linen, as in damask table-cloths, and afterwards emphasised by the needlework.

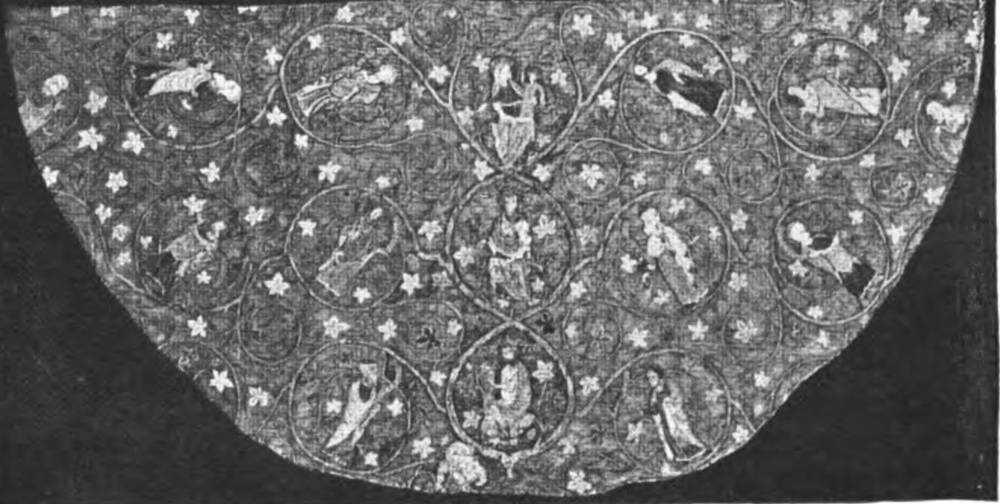

Thirteenth Century Chasuble (English). “In the South Kensington Museum.”

Like sculpture and painting, in its early and medieval forms, the most splendid achievements of needlework were dedicated to religion, and had their place in its functions, the accessories of symbolic and sacramental ritual. Perhaps some of the most magnificent specimens of the art and craft of needlework are to he found in the class of ecclesiastical vestments.

From the symbolic, severe, and mystic dignity of the embroidered designs of the earlier centuries of the Christian era that have been preserved — say of the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries — which retain traces of Byzantine influence, to the floral and decorative freedom of those of the sixteenth century onwards, we may see a wonderful series of examples of methods of needlework expression, governed by motives of ceremonial splendour.

Closely allied in spirit and method were the heraldic embroideries contemporary with these, which set forth in all the beauty of material and splendour of texture, gold, and colour, the bearings and badges of feudal families, of states, and of cities. The colour combinations and devices of heraldry, taking Gothic models, are peculiarly adapted to [146/147] decorative expression by means of the needle. The necessary boldness of design, and the typical selective characterisation of form, the frank and ornamental system of coloration, all lend themselves to its remarkable adaptability to the various methods and materials of needlework, from 'the finest piece of delicate silk work on the scale of a book-cover to the boldness of a large applique hanging.

There is probably no more effective method of covering large surfaces, such as lower wall spaces and large doorways where draperies can be used, than by designs in appliqué needlework of an heraldic character. Much, of course, depends upon the design- — upon good (if simple) form of silhouette, good spacing, appropriate choice of scale, and harmonious if bold colour scheme. But these considerations are common to all decorative art.

Portion of a Cope (English Fourteen Century). “From a Drawing by Miss Hunter in the South Kensington Museum.”

Appliqué needlework, by the judicious and imaginative use of textile material, may have a richness and distinction all its own, and possess qualities which no flat painting or inlay can really rival. We have only to consider the different qualities of surface and texture represented by linen, by wool, velvet, satin, and silk, and the power of expression and emphasis of the needle in defining and uniting them — to realise the range and resource of the textile palette, in fact — to be convinced of this. Yet needlework has this in common with the art of design generally — that it is not dependent upon richness or costliness of material. A good and suggestive design, well spaced and judiciously treated, may be most effectively and adequately expressed on linen with crcwels, or cottons, or flax-thread, and the result may be highly decorative.

Needlework, too, has the advantage over many other arts that it requires but little space. Its materials are few, light, and portable; it is an art that can be practised anywhere, requiring no expensive plant, or even any special sort of workshop or studio. It is an entirely domestic art, and its greatest charm is its personal and homclikc character aml suggestiveness.

It was a gratifying thing to see so much good work of this kind among the works in the national competition at South Kensington last summer, both as to design and execution. Much depends, as to choice of material and treatment, upon the object and purpose of the work, its scale, position, and relations to its conditions and surroundings — the same considerations, in fact, which govern all decorative art.

I think we might discern very distinct differences of aim in needlework which should naturally regulate the treatment and choice of material. When the design and expression is of a very abstract character, and its decorative effect mainly [147/148] depends upon arrangement and quality of line, one would say the simpler the better, since the ideas are conveyed by means of suggestion rather than by any attempt at realisation of form in 'its full substance and colour.

Designs of symbolical or typical figures on a large scale, for instance, can be rendered effectively, if the drawing be simple, in outline of one, or of various colours, in thread or crewels upon- an unbleached coarse linen ground.

Herald’s Coat of Philip II.

Such designs as some of those of Sir Edward Burne-Jones, where the decorative effect depends rather upon the disposition of the lines, their quality, and the sentiment of the figures than of qualities of colour, texture, or surface, can be appropriately rendered in a bold but closely-stitched outline which gains a certain richness owing to the relief of the needlework from the ground. The chief difficulty in treating figures in needlework lies with the faces and features, where the expression is apt to be distorted by the buckling of the material under the tension of the stitches, and of course the slightest twist of a line or displacement of feature makes all the difference. So that it may sometimes happen that what is intended for an expression of gentle benignance is apt to become a grin. I am afraid that in needlework, as in other things, there is but a step from the sublime to the ridiculous.

The only way of avoiding this pitfall is in getting very simple and straightforward drawing to follow, which gives no complexities, and conveys the expression with the utmost economy of line. Large scale faces, owing to greater clearness and openness of drawing, are probably easier for interpretation by means of the needle than small ones, and a profile easier than a full face. When a face is filled up with stitching to give the effect of the full local colour, and the outline becomes distorted, slight corrections to counteract it can be made by painting in lines or additions to lines which may be followed by the needle. If faces and figures are used, it is better, however, to struggle with the difficulties and make it throughout a genuine piece of needlework than to fly to the specious aid of another art, as was done in the last century, in those specimens of silk work we have seen on fire-screens, or even assuming the form of framed pictures, where the faces are pain/rd in, the Worker having exhausted the resources of the silk in the endeavour to imitate the effects and quality of painting. The painted faces always remain patches more or less, and have. no real relation to the needlework. (To be concluded.)

Second Part

Where the whole gist and beauty of needlework lie in the qualities of surface and texture over and above that of form and abstract or symbolic expression, material becomes of great consequence, as, for instance, when we desire to work a design of birds and flowers, for the purely decorative beauty of their natural tints, and when the work is intended for comparatively small panels, screens, or hangings near the eye.

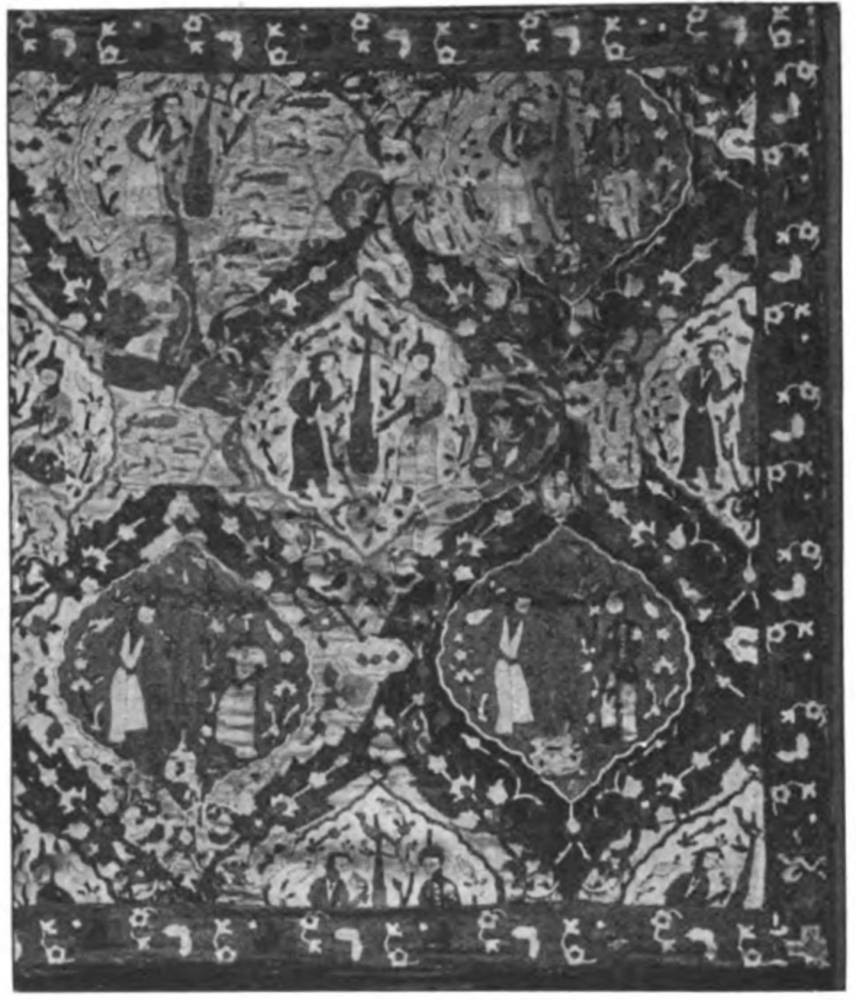

Left: The Five Senses. Coverlet of Light Red Linen, worked in coloured threads. (Sixteenth Century German), Right: Hanging of White Cotton. (Persian Eighteenth Century.) [Click on images to enlarge them.]

If a peacock were our subject, and we desired to present the bird in all its glory, we should naturally choose the lustrous surface and sheeny quality of silk to work in, and in that material might approach as near to nature as perhaps it is possible to do in any art, since the natural beauty of the silk, by means of cunning stitches, is enhanced by the way in which the light falls upon its surface when worked; and in meeting that contingency regarding it as an essential condition of the work, and making the most of it—all the skill and resource of the worker, all the art and craft of the needle, may be exercised. Look at a peacock in his fresh plumage, as he may be studied any day in Kensington Gardens by the Serpentine, with the promise of a fine London spring morning. See him on the grassy slope, the tender green of the new springing grass leading up to, as the highest note of the harmony, the flashing gold and emerald of the tail coverts.

There are, perhaps, no other decorative methods which could reach the pitch of brilliancy in the rendering of such qualities of colour as is attainable in silk embroidery, and none can rival it in beauty of texture and surface, and therefore in fidelity to the character of plumage.

The atmosphere, which makes a difference to our vision, only painting can express, but that is its prerogative, and the attempt to imitate the special qualities of painting in any other art is a mistake and quite beside the mark.

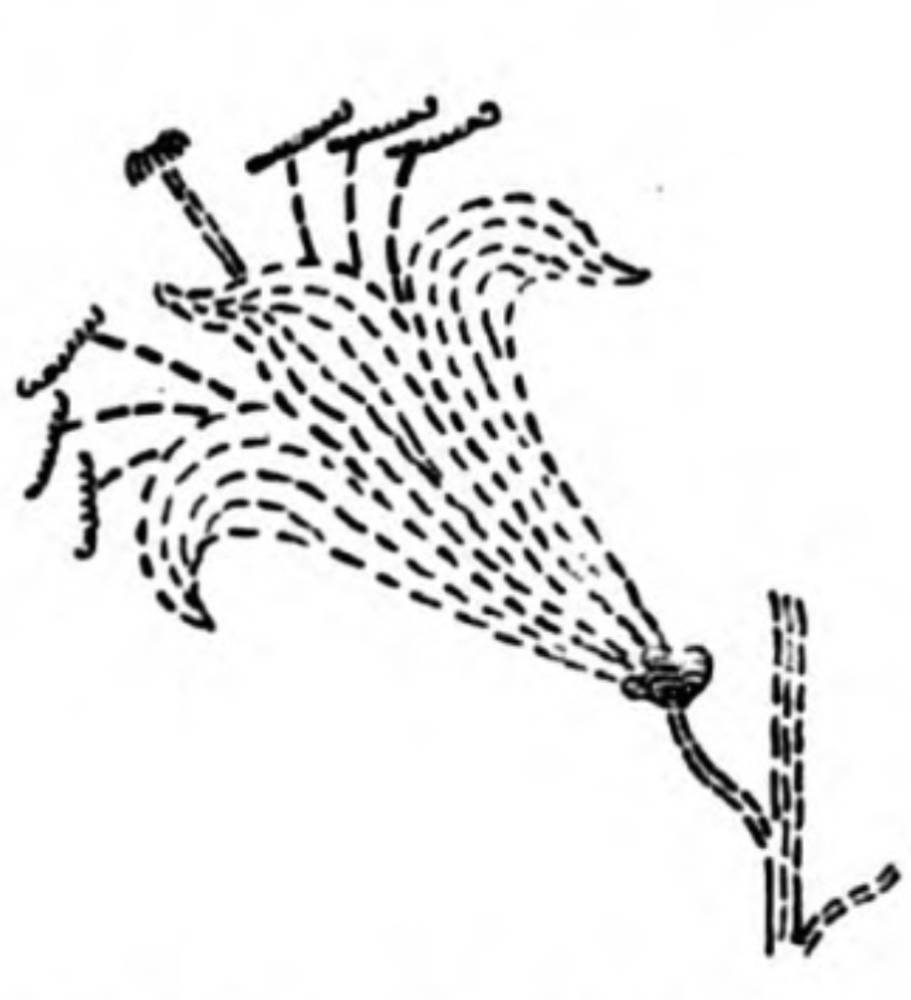

Perhaps the best examples of beautiful silk work in the rendering of birds and flowers are those of [197/198] China and Japan, which for fineness, firmness, and precision of Workmanship, brilliancy of colour, and characterisation of natural form are wonderful. Both birds and flowers lend themselves peculiarly well to representation in needlework, not only because of their obvious decorative value, but also owing to the fact that both the structure of feathers and the structure of flowers and leaves can be rendered with close fidelity by means of the needle. A feather, for instance, very obviously adapts itself to representation by stitches, and in fact it might almost be said that in this case representation and imitation are synonymous — by no means always the case. The feather, by the way, gives its name to a particular stitch familiar to needlewomen.

Three of Crane’s uncaptioned examples of flower and leaf patterns.

The structure, colours, and surfaces of flowers and leaves can be expressed with extraordinary fidelity in needlework, and too much attention can hardly be given to the study of the direction of line which characterises in nature the different types of leaves and flowers, for not only will the design be stronger and more full of character, but have more beauty where these things are observed. It is tolerably evident that the nature of a leaf (of, say, a bay or laurel) and the law of its growth are conveyed with a better sense of design if it is represented by stitches springing from the central stem and sloping upwards towards the point, than they would be if placed the reverse way and nature contradicted. A leaf of the plantain or arum character and the palm tribe, on the other band, would be represented by vertical stitches diminishing towards the point. It would be possible to work leaves, say, like lime and hazel, by long horizontal stitches at right angles to the centre stem, and afterwards cross them by single lines of stitching to express the veining, after the method known as “laid” work (p. 199) we may find in Persian and Portuguese and old Italian silk work. The stems of trees are very suggestively expressed by a series of vertical stitches crossed by closely laid horizontal ones, which pleasantly recall the texture and surface of the bark.

Left: One of Crane’s uncaptioned examples. Right: The Tree of Life. Linen Cover Embroidered in Coloured Silks. (Persian) [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The lines of structure in flower petals, again, demand different treatment, though there is no doubt more range for varied treatment. A rose, perhaps, might be treated effectively by stitches laid either horizontally or vertically (or by satin or feather stitch) according to the degree. of convention, realism, or relief desired, though the best means of obtaining the proper colour value would be of more importance here, perhaps, than the direction of line. The lily, however, would naturally be worked on the same principle as the palm leaf, the stitches tapering longitudinally towards the points of the petals or worked in the laid method before mentioned.

Gold thread has always been a fine decorative resource in embroidery, and when judiciously used gives a very rich and splendid effect. It may be 198/199] used throughout a design as an outline to emphasise the silhouette of, or clear the colours of, an arabcsque of flowers and leaves (somewhat after the method of cloisonné enamel); or it may be used to heighten the effect of parts only and used in masses, as in the case of an aureole around the head of saint or angel, or to distinguish precious things, as gold ornaments, armour caskets and vessels, much on the same principle as such things were introduced in mural paintings by the early Italian painters, raised in gesso and gilded.

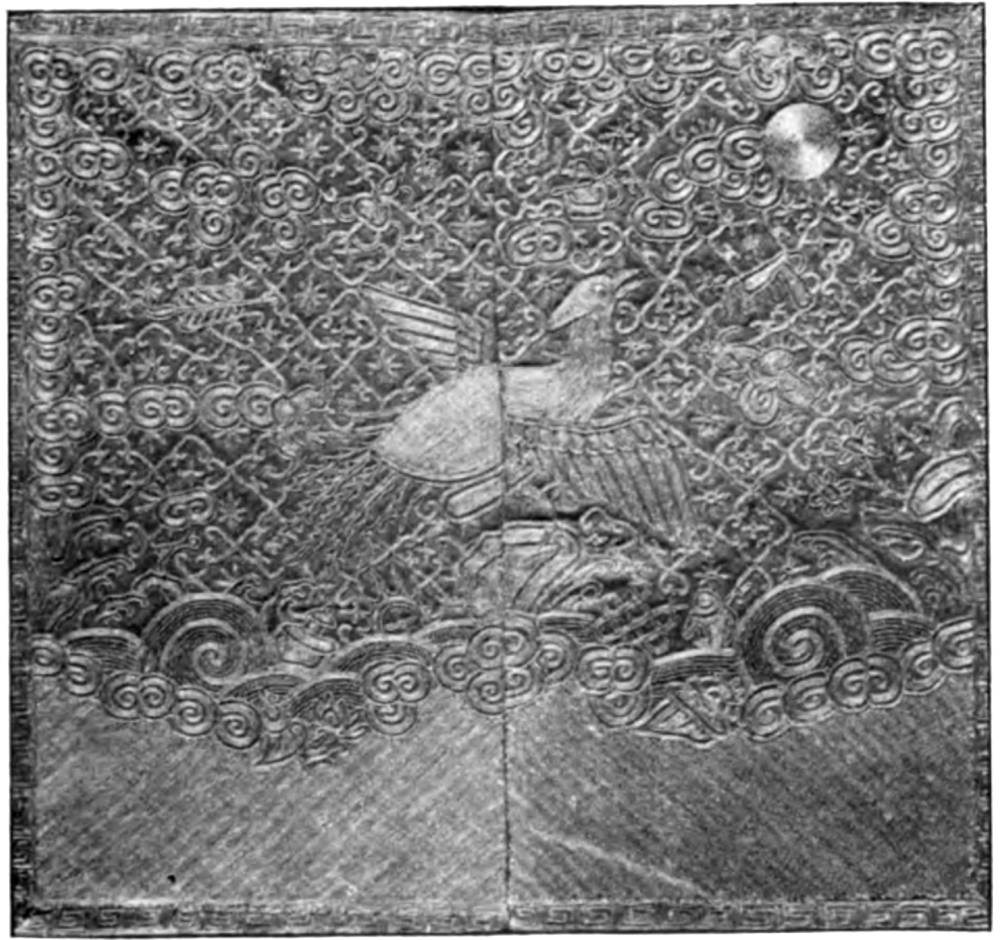

Left: Carpet of White Cotton. Embroidered in Coloured Silk. (Persian, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century.) Right: Square for Mandarin’s Robe. Gold Thread laid. (Chinese)

The Japanese kimono use gold effectively in embroidering parts of a printed design, while other parts are enriched by coloured silks, and others left in the printed pattern. Persian and Indian printed cotton and linen hangings and colours are often found embroidered upon wholly or in part. This suggests that the print was originally intended as a guide to the embroiderer. The Japanese, in their large chain-stitch worsted embroideries of figures, generally rather dark and sombre in colour, frequently introduce large disks of gold thread with wonderful effect and apparently [199/200] solely with ornamental purpose, the thread in these disks being spirally twisted round and round from the centre and stitched down or laid on to the fabric by fine thread. Upon the masses of gold thus formed the light falls into broad radiations of shade and shine, planes of luminous gold with all sorts of variations of surface, so that the effect is extraordinarily bold and rich. We have besides from the Japanese cmbroideries entirely of gold thread, which are very wonderful. The use of gold in Cretan, Syrian, and Persian embroidcries is very effective. Silver thread, owing to its liability to tarnish, is difficult to use, though this does not appear to have been an obstacle in old work. In a sixteenth-century cope in my possession silver thread is very beautifully wrought into the colours of the fanciful pomegranate-like fruits and flowers which form the pattern. The metal has no doubt blackened a good deal with time, but a certain charm attaches to its present condition as of a kind of subdued crystallised splendour. The method in which the flowers and leaves are worked, the direction and use of the stitches, etc., are well worth study.

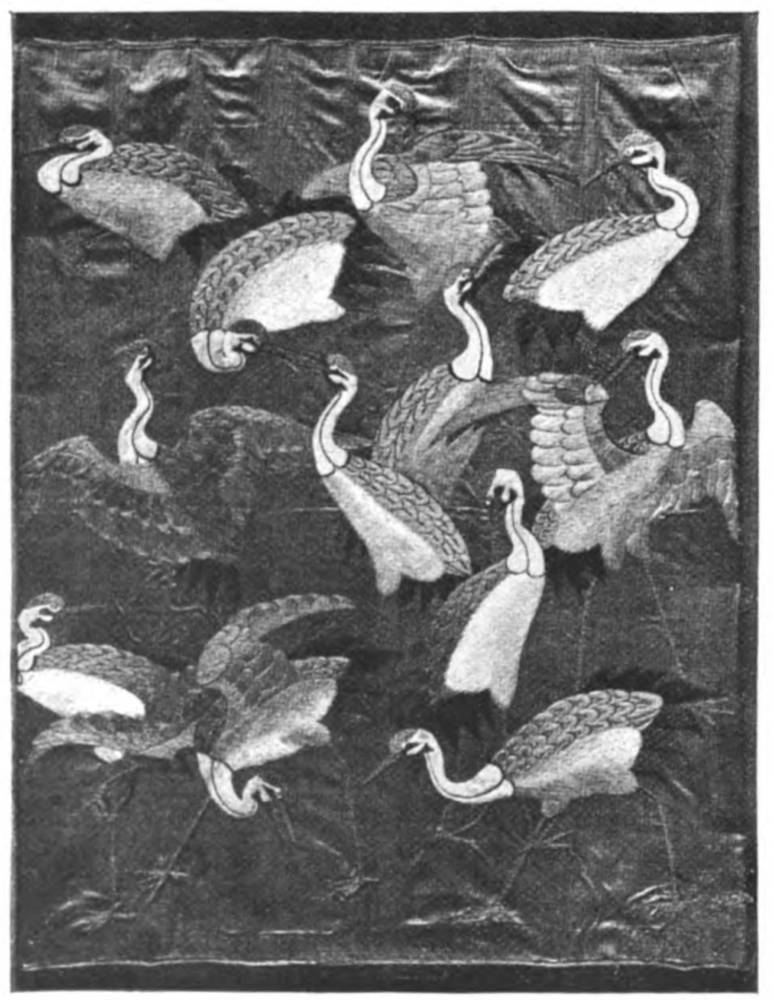

Left: Pillow Mat Embroidered with Storks. (Chinese.) Right: Crane’s drawing of Laid Work.

To revert again to such forms, as their natural characteristics

are capable of being expressed by needlework, animals may

be included, with flowers and birds, as

being extremely adaptable, their forms being

decoratively valuable as patterns, while the

colours and textures of their coats, the direction of the hair and

characteristics of its textures, distinctive

markings, all belong to the methods of expression by the needle,

[200/201]

much in the same way that was observed in the

case of feathers and leaves. The flowing mane of

the lion, the black stripes of the fiery tiger, the

spots of the yellow leopard, the rough coat of the

wild boar, the dappled sides of the fallow deer, the

woolly fleece of the sheep, all seem to fall into the

range of what might be called the natural expression

of the needle, which by the very necessity of

its fibrous method can characterise the rough and

the smooth, the wavy, or the straight.

In the adoption and adaptation of the forms of nature by any art or form of handicraft we should expect some distinct and characteristic treatment, separating them in the particular design and material from any other; and so far from trying to imitate in one material or method effects or treatments only adapted to another, we should rather seek to obtain more distinct character by emphasizing the technical differences between one method of design and expression in handicraft and another.

Nature in all art is the great storehouse of suggestion and revivifying influence, but it is often through art—historic or traditional art—that we get the key to its fitting expression, and this is perhaps especially so in needlework. Nothing is more important in design of any kind than the use made of natural form and fact. They may only reappear in highly abstract shape after passing through the crux of ornamental and technical demands, or they may be almost a direct transcript. Much depends upon method and material, and more upon decorative use and purpose; and within this range both abstract ornament and close naturalism must have due place. Everything finally depending upon judicious individual choice, or what is called taste — perhaps more important in these distracting days than any other factor in art.

Portion of Border of a Cover in Yellow Silk. Damask Ground, Embroidered with Birds and Flowers (Chinese).

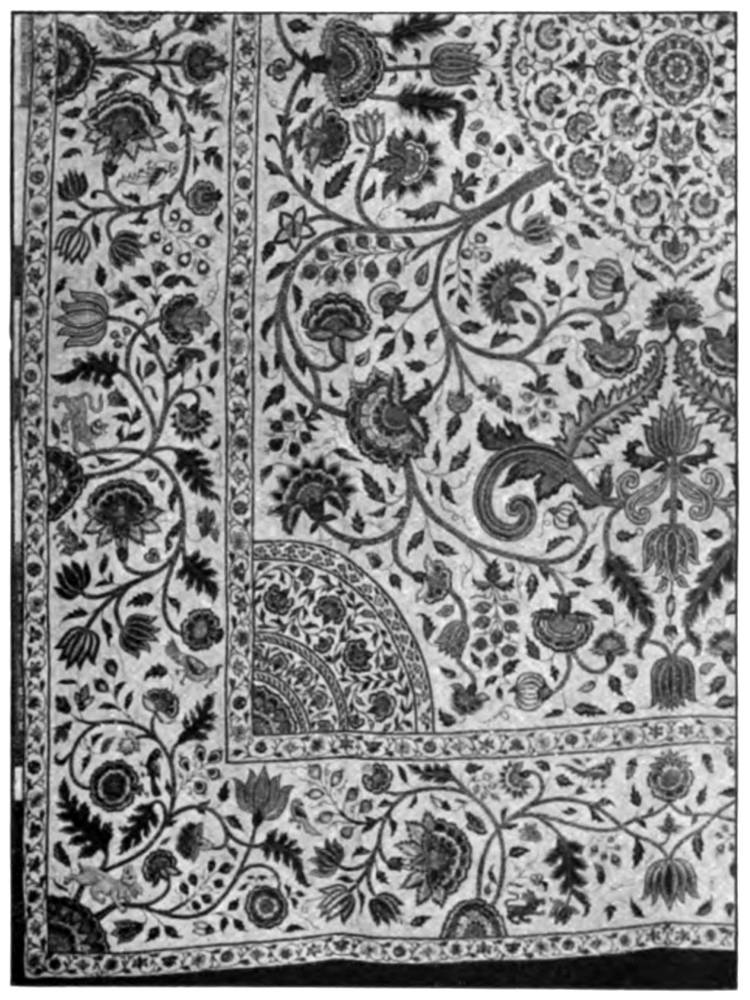

We shall find no better models for treatment of floral design in textiles than in Persian art, of which our South Kensington Museum contains a wealth of beautiful specimens. Persian floral design appears to me to be so dominated by decorative instinct and invention, that the blend of naturalism and formalism is perfect. The unity is so complete that we feel here is a world of ornamental beauty with laws and harmonies as well as forms of its own, just as natural, on its own plane, as Nature herself, because just as much the result of adaptation to conditions. We can identify the rose and the pink and the iris, the palm and the pomegranate in Persian embroidery, but they are each of a specialised decorative genus perfectly adapted to their purpose, and governed by the principle of controlling boundary before alluded to.

Now I feel that the ideal to aim at in needlework design is something distinctive and inseparable from the characteristics and conditions of the craft. We should not be content with merely imitating either nature, or Persian work, or Indian, or Chinese, or Japanese, or Cretan, or Italian, or Spanish. If em— broidery is to be a living art it must, like the other arts, find its own distinctive forms of expression, gathered from many sources, perhaps, and having roots in the traditions of the past, but belonging to the present.

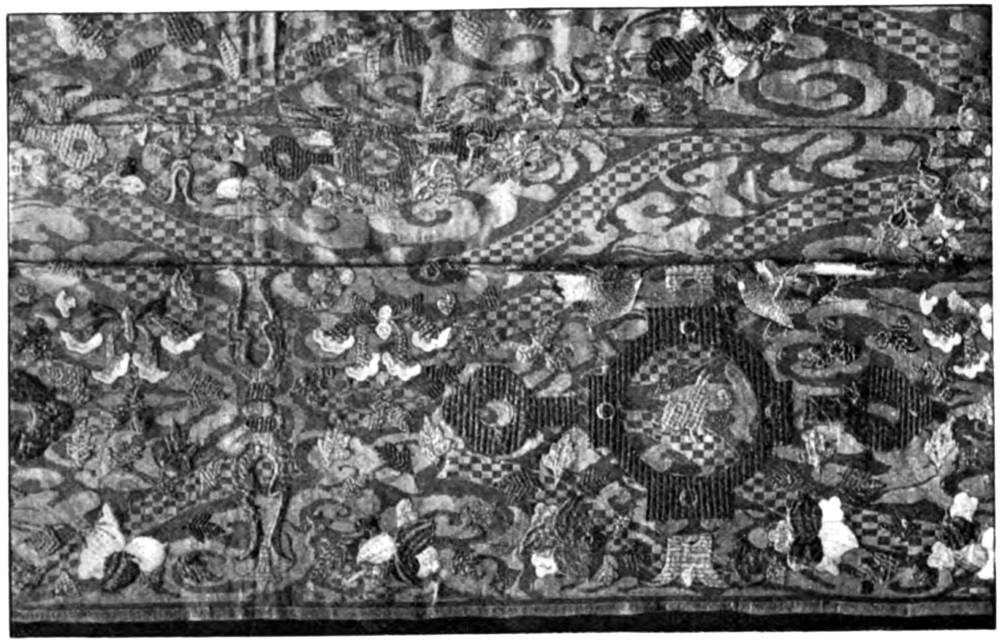

Left: Cover of Dark Blue Satin. Embroidered with Storks in Silk in Gold and Silver Colour Silk Threads. (Japanese). Right: Portion of Embroidery Formerly Belonging to Tippoo Sultan . (Indian)

A general survey of needlework as part of the great historic record of design, after its rude and primitive efforts, shows us, in the course of its artistic development, exquisite workmanship perfectly united to decorative beauty both of form and colour; we may see, perhaps, the results of patient years of labour lavished upon a few square inches of fine silk or gold work; we may find the sacred symbols of religious faith, the badges of family and race, the frank colour and artless traditions of the peasant, the proud ensigns of nations and peoples, the little child's sampler, the tour de force of the expert, the quaint shadows of human follies, fancies, and fashions, and the romance of faded lives—all these the needle has recorded for us in unmistakable characters, so that there can be no question of its place in art and history, its human interest, its range of suggestion and expression, apart from its undoubted decorative and domestic value.

Sampler in Coloured Silks. (Spanish, Seventeenth Century.)

Yet all this decorative richness and historic significance has sprung out of the common ground of necessity and utility—the necessity of the needle and thread applied to the fundamental utility of clothing. So it is with any handicraft: pursued under natural, human, and free conditions it is certain, sooner or later, to blossom into design. So it comes about, I suppose, that Cinderella, stitching towels or marking linen by the kitchen fireside, is transformed in the course of time into a dream of decorative beauty in a fairy palace.

It is well that the technical methods and mysteries of needlework should be studied, just as we should study the grammar and literature of a language while endeavouring to write or to speak in it; the traditional stitches adapted to the different kinds of work, the expression of surface and decorative effect, and so forth. What beautiful works samplers can be made may be seen in the fine Spanish specimens of the seventeenth century in the South Kensington Museum, one of which exhibits forty different patterns of stitches. Yet I presume there is no finality in the art of the needle, and it may be possible to invent or adapt new ones and new forms of design. The more thoroughly the resources and limitations of a craft are understood the better for the work, since in meeting conditions we really conquer them, and working freely under them, are more able to make them the medium of new motives in design.

A few years ago, I remember, in New York the head of a school of industrial design there wrote to me, and he said, “We have a primitive art which knows nothing of technique, and we have an up-todate art which knows nothing but technique.” That, perhaps, is a condition of things characteristic of the age. Let us take care that between the two stools art does not fall to the ground. Let us see that while we strive to perfect ourselves in methods of expression—to master the technical difficulties and necessities of any art or handicraft—we do not lose sight of the end in endeavouring to realise the means. Let us not forget that every art is a method of expression, and that the highest expression of any art is, after all, the expression of beauty. And how can that expression be full or perfected unless it springs out of the joy of life and pleasure in handiwork, and answers to the spontaneous demand of the human spirit for harmonious conditions?

NOTE.—In the first instalment of this article, which appeared in the January number of THE MAGAZINE OF ART, the reference to the herald's coat of Philip 11 illustrated on p. MS was inserted by mistake. The example intended to be referred to (on p. 144) is one of the time of our James II, and is in the South Kensington Museum, but not illustrated in the article. The herald's coat was, of course, given as an example of appliqué and its effectiveness in rendering heraldic devices.

Bibliography

Crane, Walter. “Needlework as a Mode of Artistic Expression.” The International Studio 22 (1898): Part One, 144-48. Second Part, 197-202. Hathi Trust Digital Library online version of a copy in the library of University of Chicago. 22 January 2018.

Created 21 January 2018; last modified 31 October 2023