Many thanks to the National Portrait Gallery, London, for permitting us to use the images in this review. Apart from the Kelmscott Cabinet and the Kelmscott Chaucer (click on these image for more information), they are for the purposes of the review only, and should not be reproduced elsewhere without permission from the copyright holders. Please click on all the images to enlarge them. The review has been arranged collaboratively, and formatted and linked by Jacqueline Banerjee.

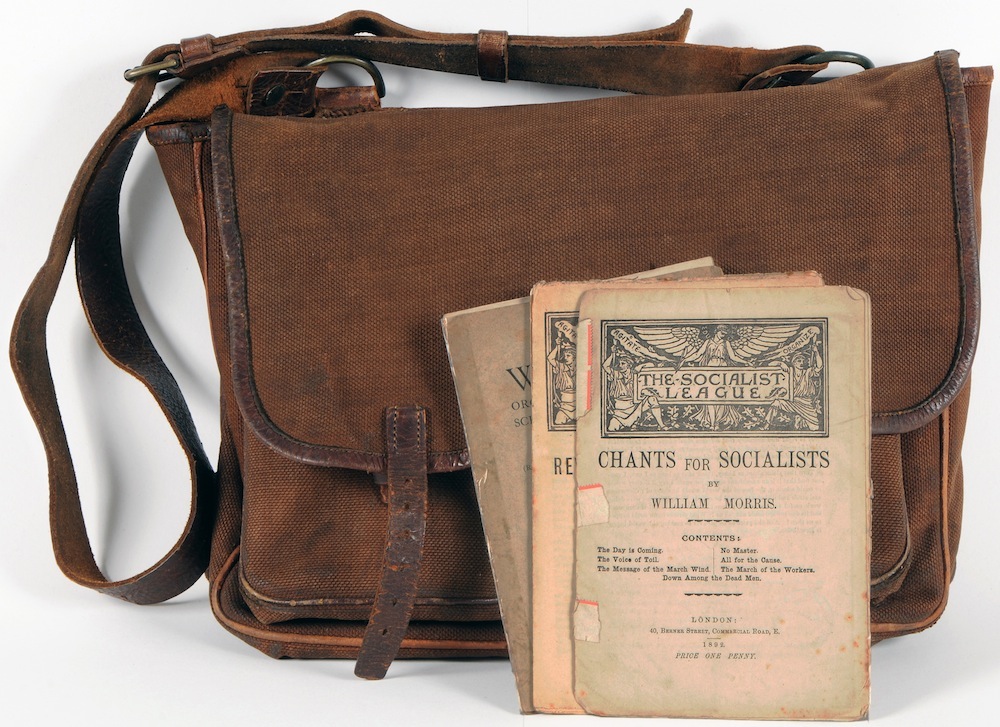

isitors to the Victorian Web will need no introduction to William Morris (1834-1896) or to his multifarious activities. "One more exhibition devoted to him and his circle!" they might be tempted to say after the comprehensive Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde Exhibition held at the Tate only two years ago. Indeed, some of the objects which feature prominently in the current National Portrait Gallery Exhibition, like the Prioress's Tale Wardrobe of 1859, now at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, to which it was bequeathed by Miss May Morris in 1939, were already among the main attractions of the Tate Exhibition. This was designed by Webb and painted by Burne-Jones (with his 1868 portrait by Alphonse Legros, now at the Aberdeen Art Gallery) for the newly-wed Morrises' home, Red House, at Bexleyheath. Likewise, William Morris devotees will be familiar with the famous satchel [see "The Socialist Legacy" below], now at the William Morris Gallery, Walthamstow, which he used when handing out his Socialist literature to potential converts to the cause.

La Belle Iseult (1858), © Tate - Bequeathed by Miss May Morris, 1939.

In the same vein, the visitor to the Exhibition is greeted by the famous portrait of William Morris by G. F. Watts (1870) which is on permanent display in the 19th century section of the Gallery. Even "worse," the "What's On" pamphlet listing the special events and exhibitions organised by the National Portrait Gallery from September to November has the well-known picture of La Belle Iseult on its cover – it is of course presented as one of the highlights of the Exhibition.

All this to say that there is a prima facie case for suspecting that this Exhibition will have a serious dimension of déjà vu for the William Morris enthusiast: what is the point of paying £14 (incl. donation) to see what can otherwise be seen free of charge outside the Exhibition? But then, there are two answers. First, real amateurs of William Morris and all that he stands for never tire of seeing the satchel, the pamphlets and membership card for the Hammersmith Branch of the Socialist League illustrated by Walter Crane, the Chants for Socialists, the only painting by William Morris (La Belle Iseult), the furniture designed, decorated and made by his close friends, or the productions of the Kelmscott Press (well represented here, of course). And it is extremely moving to see an uncommon piece (now at the British Library) like his Socialist Diary, kept from January to April 1887. We can imagine how dejected he must have felt when he reminisced about his previous Sunday lecture in the entry shown, for Wednesday 30th March: "the audience was civil and inclined to agree, but I couldn't flatter myself that they mostly understood me, simple as the lecture was." Secondly, Fiona MacCarthy, the respected Morris scholar who curated the Exhibition and wrote the Catalogue,* was evidently aware of the pitfall – hence the insistence on the legacy, which takes a large part (more than half, I would reckon) of the displays. And this "legacy" dimension justifies a visit in itself.

The Socialist Legacy

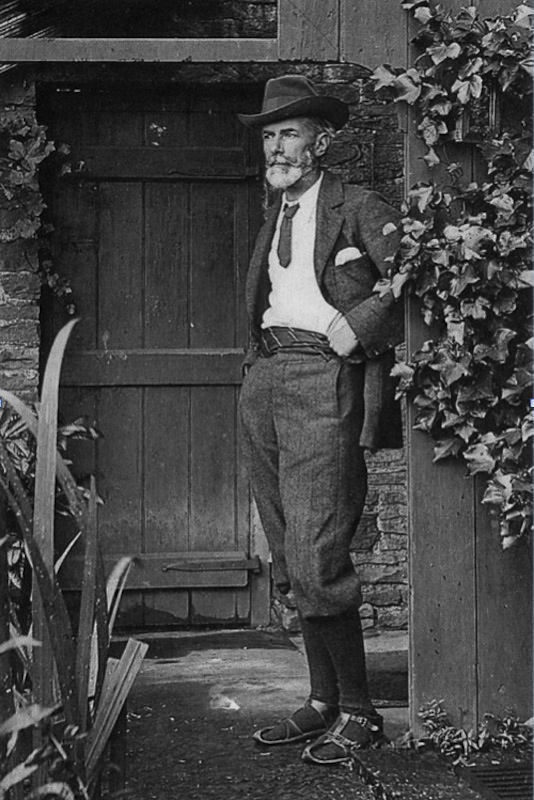

Left: Morris's satchel, © William Morris Gallery, London Borough of Waltham Forest. Right: Edward Carpenter, photographed in his sandals by Alf Mattison, 1905; copied by Emery Walker. © National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG x87106.

Many will be familiar with Orwell's famous remarks in The Road to Wigan Pier (1937) on the archetypal Left-wing activists of his time : "One sometimes gets the impression that the mere words 'Socialism' and 'Communism' draw towards them with magnetic force every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, 'Nature Cure' quack, pacifist, and feminist in England." But it is not always realised that the "sandal-wearing" can actually be traced to Edward Carpenter (1844-1929), who is reported to have been the first to introduce sandals from India (some are shown). Indeed, he started to make them for sale with his homosexual partner at Millthorpe, near Sheffield, in 1889, eventually setting up a workshop in Letchworth. Unfortunately, he wears conventional shoes in his full-length portrait by Roger Fry (1894) – but there is also the famous photograph of 1905, by Alf Mattison, in which the sandals which he designed are clearly visible. Thus began the "Socialist" legacy (Carpenter was a founding father of the Independent Labour Party, known as the ILP).

The Arts and Crafts Legacy

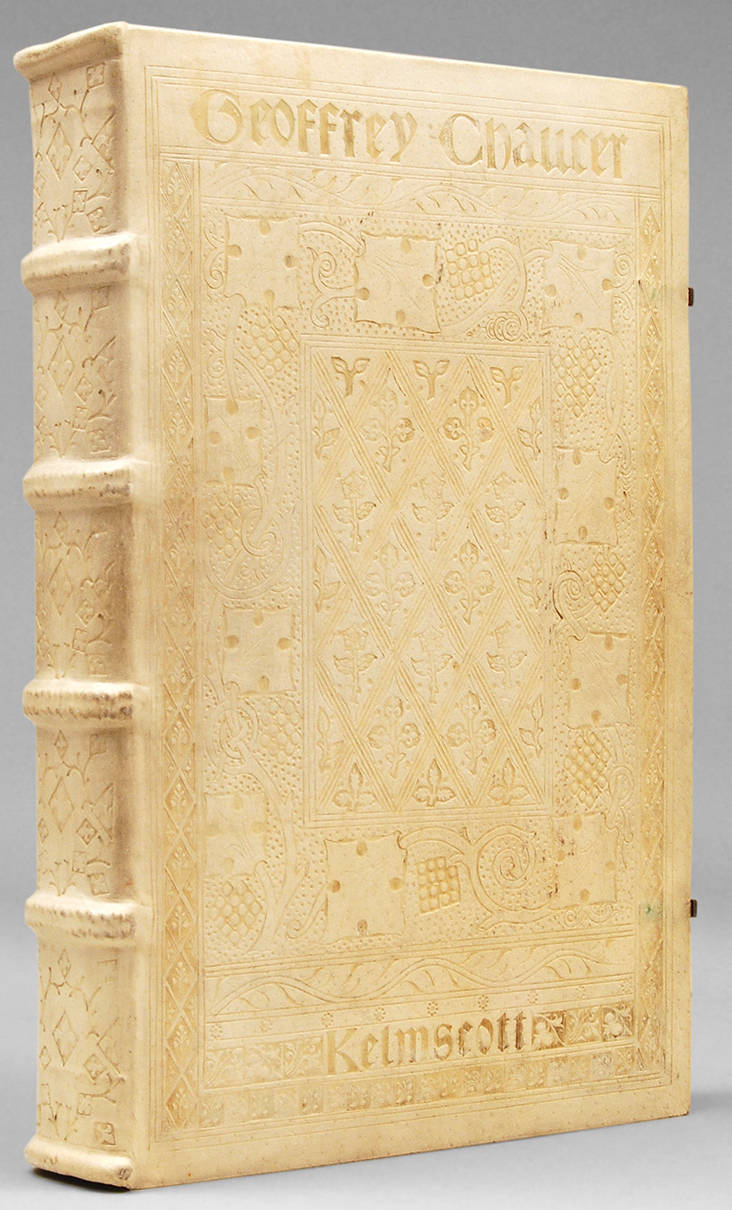

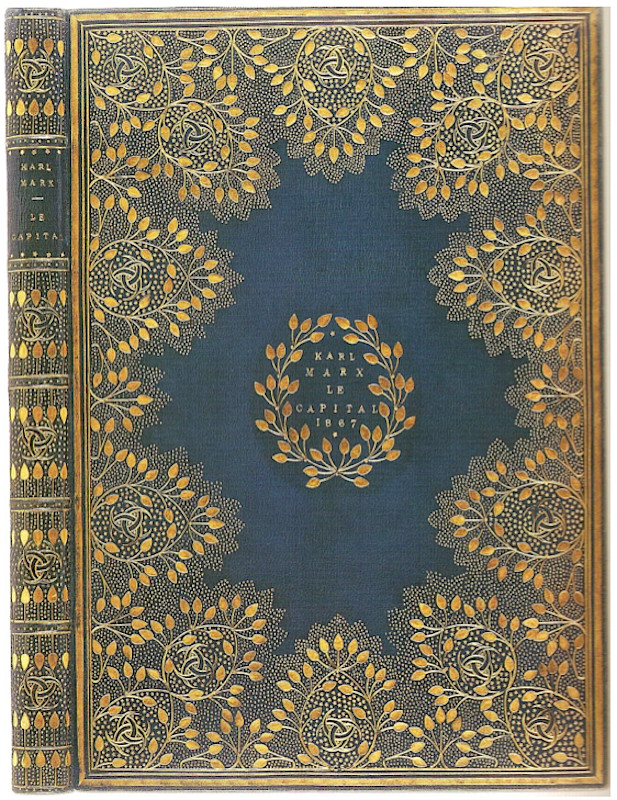

Left to right: (a) Vase and Cover (1888-1898), by William De Morgan © Victoria & Albert Museum. (b) One version of the Kelmscott Chaucer, signed on the rear inner dentelle, "Doves Bindery 1897," © Peter Harrington, Rare Books (click on the image for more information). (c) Marx's Le Capital (1884), © Wormsley Library.

But there was also the "Arts & Crafts" legacy, with a rich display of objets d'art and other productions now associated with William Morris and his circle. There is for instance a magnificent Vase and Cover (1888-1898) lent by the Victoria & Albert Museum and designed by William De Morgan, who had been encouraged by Morris to open a pottery workshop. The anecdote circulates among Morrisians that it was during a dinner party that William and Jane Morris persuaded their lawyer friend Cobden-Sanderson to take up book-binding. Indeed around 1884 he opened a workshop, abandoning his law practice, and three years later he was at the origin of a new group named the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society – thus launching both the actual movement and the label associated with it. Cobden-Sanderson became a great book-binding designer and practitioner with his Doves Bindery. His several versions of the bindings designed for the Kelmscott Chaucer are commonly shown (one – the copy offered by Morris to Emery Walker – in half-pigskin with the oak boards left bare being in the Exhibition), but not his famous 1884 binding of William Morris's precious copy of Le Capital (in French because there was no English translation yet, and William Morris read French more easily than German).

Verses from The Earthly Paradise with added lines from Sir Walter Alexander Raleigh. © William Morris Gallery, London Borough of Waltham Forest.

Since charity begins at home, May Morris was also among those who benefited from her father's enthusiasm for the highest forms of manual work – in this instance embroidery and stitching, exemplified here by her superb "June" Frieze with View of Kelmscott Manor of c.1900, which hung in her sitting room at Hammersmith (a photograph of 1923 shows it on a wall papered in "Willow Boughs," together with other objects associated with her fond memories of the Manor).

In the field of furniture, besides tributes to Ernest Gimson & the Barnsley brothers, we have the opportunity to look at the little-known Oak Cabinet, now in the Arts and Crafts section of the Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum, designed by C. F. A. Voysey (1857-1941) in 1899, to house a copy of the Kelmscott Chaucer.

Perhaps the most insightful "legacy" suggested by Fiona MacCarthy in this section is the connection made with Ebenezer Howard (1850-1928), with a portrait of 1912 by Gerald Spencer Pryse now in the First Garden City Heritage Museum, Letchworth: the continuity between the idealised Nowhere and the ideal Garden City seems difficult to refute. The Masterplan for Letchworth by Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin (1904) usefully illustrates how the abstract concept of The City Beautiful was now to be concretely translated into brick and mortar.

The Adam and Eve Garden Roller by Eric Gill, 1831. © Leeds Museums and Galleries (Leeds Art Gallery).

In the next room, whose theme is "Heavens on Earth (1918-1939)," we leave the more obvious connections with William Morris and his direct "disciples," to enter what will appear as controversial to many visitors – the claimed legacy often arousing feelings of "not proven." If the potter Bernard Leach (1887-1979), shown at work in San Francisco in 1950 on a video, can rightfully appear as a direct descendant, one is not convinced in the case of the chosen piece by Elizabeth Peacock (1880-1969), her Art Banner of 1938. And it seems hard to inscribe the "naughty" (not really "erotic," as described by the Gallery in its promotional literature) Adam & Eve Garden Roller of 1931 by Eric Gill (1882-1940) in the William Morris tradition, as none of his many works, in whatever form, had the slighest bawdy dimension as far as I am aware.

Commenting upon it during the Press View, Fiona MacCarthy, who has written a biography of him (1989), remarked that Gill had an obsession with sex – something which certainly cannot be said of William Morris and the artistic and intellectual standards which he strove to restore or establish. Far more relevant for the "legacy" is Gill's exploration of new type faces (e.g. in his The Lord's Song of 1934) and his militant pamphlet on Unemployment (1933). Curiously, we have a blank for the war years, considering that Utility Furniture had strong links with the Morrisian ideals of plain design combined with the best working methods. The wartime issues of The Woodworker are full of examples of how to make do with native timbers – notably English oak, the prime material of Morris & Co. – without neglecting strength and durability. The fancy veneers and exotic woods of the Victorians, which Morris and his friends found so ugly, had no room in the designs offered by Utility Furniture.

Art for the People

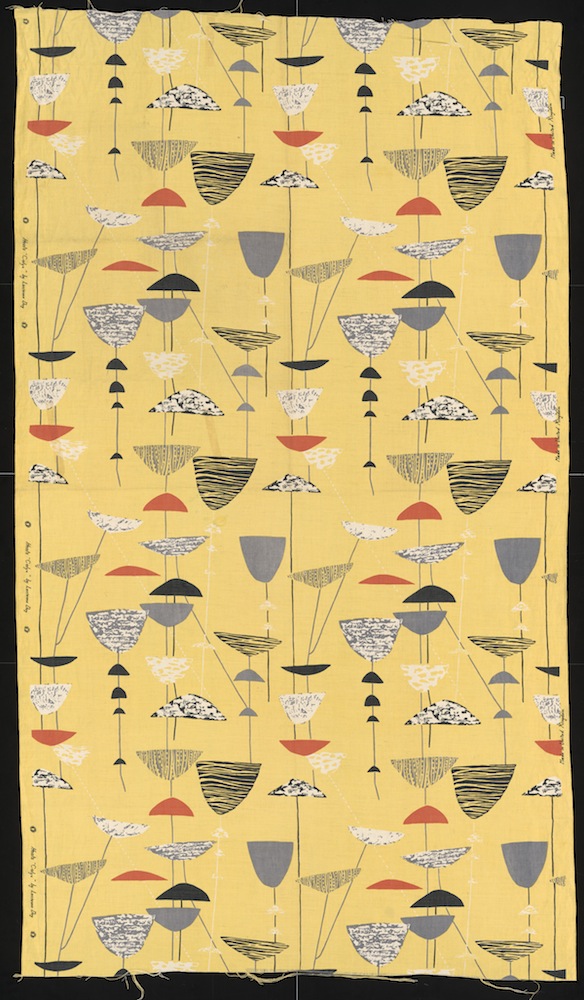

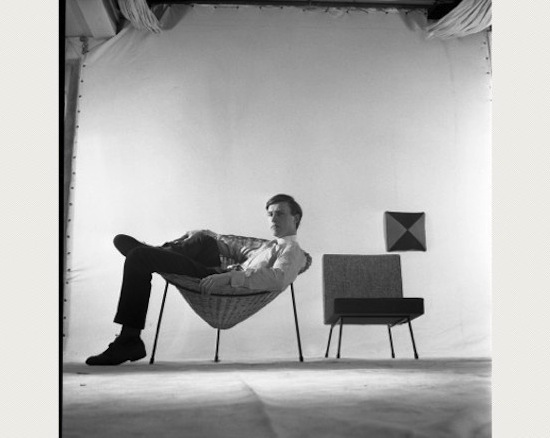

Left to right: (a) Festival of Britain poster by Abram Games, 1951. © V&A, London, 2014. (b) Calex furnishing fabric, © V&A, London, 2014. (c) Ray Williams: Terence Conran and His Cone Chair, 1950s © Estate of Ray Williams.

So, the last section, entitled "Art for the People," takes us straight after 1945. Visitors will inevitably argue whether Clement Attlee (with a fine photograph by Karsh, 1944) can be seen as a practitioner of William Morris's idea of Socialism. We also have Heron's idiosyncratic 1950 portrait of Sir Herbert Read (1893-1968), described in the Gallery's records as "critic, poet and writer on art" – a label equally applicable to William Morris, the more so as Fiona MacCarthy likes to remind us that in his time William Morris was known primarily as a great poet. But the central theme of the post-war display is evidently the Festival of Britain of 1951 – a theme explored not only through its famous poster and its designer Abram Games, but also through badges and other mementoes of the Festival. Again, one may doubt whether William Morris would have approved of this mass event replete with overtones of patriotic pride – after all he and his young friends had been disgusted by the display of Victorian bad taste at the Great Exhibition of 1851. And the "Britannia" helmet on Games's poster would obviously not have met with his approval.

Two other displays are meant to provide the link between past and present. The first is built around another 1951 object, Lucienne Day's Calyx furnishing fabric. Lucienne Day (1917-2010) had in fact created her Calyx on the occasion of the Festival, and it was notably sold through Heal's – hence the somewhat tenuous connection with William Morris: making furnishings of beauty accessible to the widest possible circles. The same "connection" holds good for Terence Conran, and his famous Basketweave Cone Chair of c.1953, captioned as "Painted steel rod frame with rubber ferrules and a woven wicker cone with fabric covered cushion" – one is exhibited, together with a contemporary photograph. It is convincingly argued that his designs perpetuated the tradition of simple, basic chairs established by Morris, and previous rooms have both the famous "Sussex" chair designed by Philip Webb c.1860 and a type popularised by Ernest Gimson and later sold at Heal's (now owned by Conran, since 1984), the "Clissett" (1891), named after the country "chair bodger," Philip Clissett. Adding a further argument, Fiona MacCarthy reminds us that Conran (b. 1931) recently remarked: "I have a Morris-like view about not producing things only the rich can afford."

As visitors leave, they are invited to read an Afterword, with a magnificent phrase borrowed from E. P. Thompson, who wrote that William Morris was "one of those men whom history will never overtake." In a Guardian article (3 October 2014) reprised from the Afterword of the Catalogue, Fiona MacCarthy refers to a superbly iconoclastic mural which the youthful Morris would have thoroughly enjoyed: We Sit Starving Amidst our Gold by Jeremy Deller (2013) – an appropriate illustration of E.P. Thompson's remark in the 2010s. All of us who have read and re-read Fiona MacCarthy's admirable biography of 1994, William Morris: A Life for our Time, will delight in seeing the exhibits which she has assembled to make vivid and concrete the theoretical points which she so elegantly made in her study – whatever reservations one may have on some of her bolder choices, there is no doubt after visiting this Exhibition that Morris is indeed a man for our time.

The exhibition catalogue, which was printed in China — now what would the founder of the Kelmscott Press have thought of that? — is of high typographical and photographic quality. The scholarly text is impeccably footnoted and profusely illustrated – in full colour whenever appropriate. It is very usefully complemented by a comprehensive, twenty-page section of substantial Biographies of people mentioned, closely but legibly printed on three columns, from Charles Robert Ashbee, 1863–1942 to Lily Yeats, 1869–1949. In addition to giving Fiona MacCarthy's personal selection of books on William Morris and his works, the section “Further Reading” also lists recommended publications on artists, designers, activists, and thinkers associated with his lifetime circle and its legacy, updated to 2014. Altogether a magnificent complement to the existing literature on the great man and his lasting influence – and a more than adequate substitute for those unfortunate enough to be unable to visit the Exhibition.

Related Material

Bibliography

MacCarthy, Fiona. Anarchy & Beauty: William Morris and His Legacy, 1860-1960. London: National Portrait Gallery Publications, 2014. Paperback. 237x269mm. 183 pp. ISBN 978-1855144842. (Hardcover edition. Yale University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0300209464).

Last modified 24 November 2014