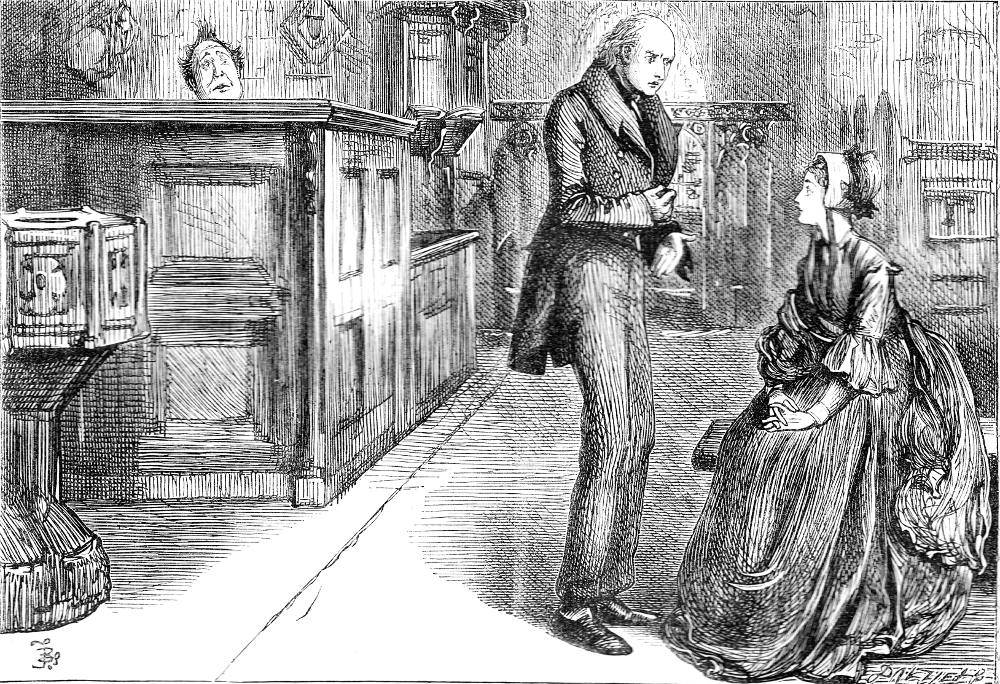

"I say," cried Tom, in great excitement, "He is a scoundrel and a villain! I don't care who he is, I say he is a double-dyed and most intolerable villain!" (1872). Thirty-seventh wood-engraving by Fred Barnard for Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit (Chapter XXXI), page 249. [To Mary Graham, Martin's fiancée, Tom Pinch denounces the duplicity of his devious employer, who, unbeknownst to them, is overhearing everything from the church pews, having fallen asleep there while Tom was playing the organ. The dismissal of Tom precipitates his departure for London, where he sets up housekeeping with his sister and undertakes the reorganisation of a private library in The Temple.] 9.4 cm x 13.8 cm, or 3 ¾ high by 5 ½ inches, framed, engraved by the Dalziels. Running head: “Mr. Pecksniff Listens," 249. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated: Struck by the Truth of Her Accusation

"He is a scoundrel!" exclaimed Tom. "Whoever he may be, he is a scoundrel."

Mr. Pecksniff dived again.

"What is he," said Mary, "who, when my only friend — a dear and kind one, too — was in full health of mind, humbled himself before him, but was spurned away (for he knew him then) like a dog. Who, in his forgiving spirit, now that that friend is sunk into a failing state, can crawl about him again, and use the influence he basely gains for every base and wicked purpose, and not for one — not one — that’s true or good?"

"I say he is a scoundrel!" answered Tom.

"But what is he — oh, Mr. Pinch, what is he — who, thinking he could compass these designs the better if I were his wife, assails me with the coward’s argument that if I marry him, Martin, on whom I have brought so much misfortune, shall be restored to something of his former hopes; and if I do not, shall be plunged in deeper ruin? What is he who makes my very constancy to one I love with all my heart a torture to myself and wrong to him; who makes me, do what I will, the instrument to hurt a head I would heap blessings on! What is he who, winding all these cruel snares about me, explains their purpose to me, with a smooth tongue and a smiling face, in the broad light of day; dragging me on, the while, in his embrace, and holding to his lips a hand," pursued the agitated girl, extending it, "which I would have struck off, if with it I could lose the shame and degradation of his touch?"

‘I say," cried Tom, in great excitement, "he is a scoundrel and a villain! I don’t care who he is, I say he is a double-dyed and most intolerable villain!"

Covering her face with her hands again, as if the passion which had sustained her through these disclosures lost itself in an overwhelming sense of shame and grief, she abandoned herself to tears. [Chapter XXXI, "Mr. Pinch is Discharged of a Duty Which He Never Owed to Anybody; and Mr. Pecksniff Discharges a Duty Which He Owes to Society," 251. Running head: "And Hears No Good of Himself"]

Commentary: Farce rather than Sentimentality Governs the Composition

The realisation of the letterpress compelled Barnard to choose between the sentimental strain of Mary Graham's dialogue and the physical situation itself: pure farce. The consequence is a somewhat theatrical scene cluttered with church paraphernalia as the illustrator juxtaposes Pecksniff's somewhat shocked expression and Tom's earnest indignation as Mary unmasks the rogue ands hypocrite. Whereas Mary in the letterpress is overcome with emotion, Barnard seems to have felt that her facial expression should be controlled, perhaps to emphasize the expressions of the other two figures in the stage farce. As Davis sums up the situation, "Tom is finally convinced that Pecksniff's not the man he thought him" (232).

Images of hypocritical Pecksniff and faithful Pinch, Various Editions (1844 to 1924)

Left: Hablot Knight Browne's Mr. Pinch Departs to Seek His Fortune (February 1843). Centre: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Mr. Pecksniff and his Daughters (1867). Right: John Gilbert's polished Mr. Pecksniff's Courtship (1863). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

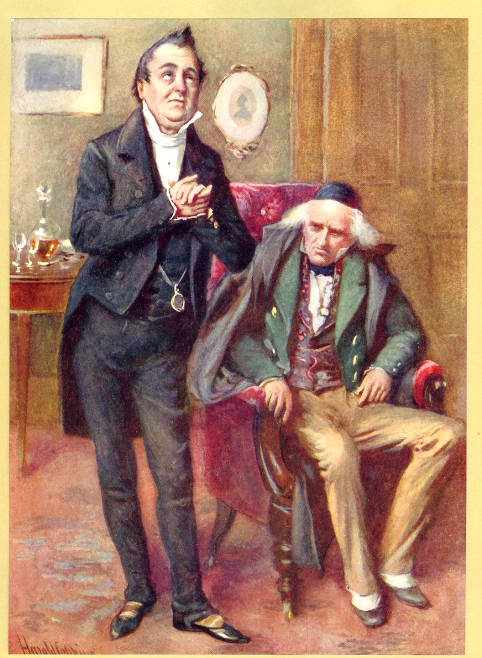

Left: Clayton J. Clarke's Player's Cigarette Card study of the humbug, Mr. Pecksniff (1910). Centre: Harry Furniss's depiction of the aftermath of Topm's dismissal, as he stands up for his sister, Ruth, Tom Pinch at the Brass and Copper Founder's (1910). Right: Harold Copping's synthesis of all former Pecksniffs, Mr. Seth Pecksniff and Old Martin Chuzzlewit (1924). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. "Martin Chuzzlewit, The Life and Adventures of." Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts-on-file and Checkmark, 1998. Pp. 229-237.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman and Hall, 1844.

_____. Martin Chuzzlewit. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1863. Vol. 1 of 4.

_____. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit, with 59 illustrations by Fred Barnard. 22 vols. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871-1880. Vol. 2. [The copy of the Household Edition from which this picture was scanned was the gift of George Gorniak, proprietor of The Dickens Magazine, whose subject for the fifth series, beginning in January 2008, was this novel.]

_____. Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 7.

"The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit: Fifty-nine Illustrations by Fred Barnard." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-Six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. Mahoney, Charles Green, A. B. Frost, Gordon Thomson, J. McL. Ralston, H. French, E. G. Dalziel, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. Printed from the Original Woodblocks Engraved for "The Household Edition." London: Chapman and Hall, 1908. Pp. 185-216.

Steig, Michael. "From Caricature to Progress: Master Humphrey's Clock and Martin Chuzzlewit." Ch. 3, Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978. Pp. 51-85. [See e-text in Victorian Web.]

Steig, Michael. "Martin Chuzzlewit's Progress by Dickens and Phiz." Dickens Studies Annual 2 (1972): 119-149.

3 February 2008

Last modified 24 November 2024