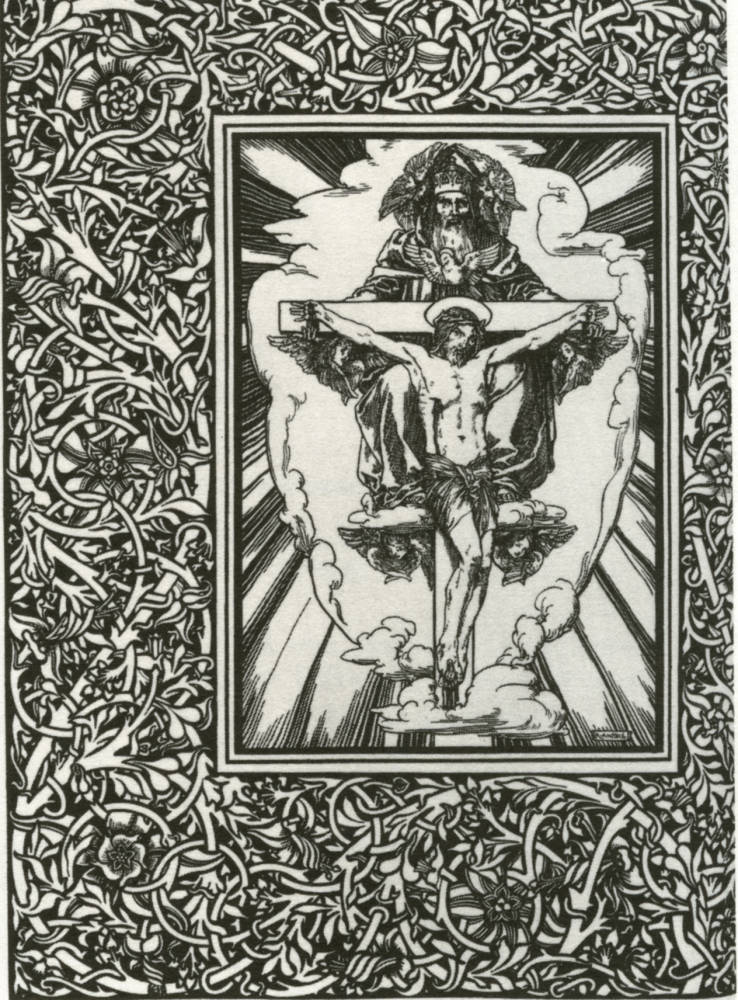

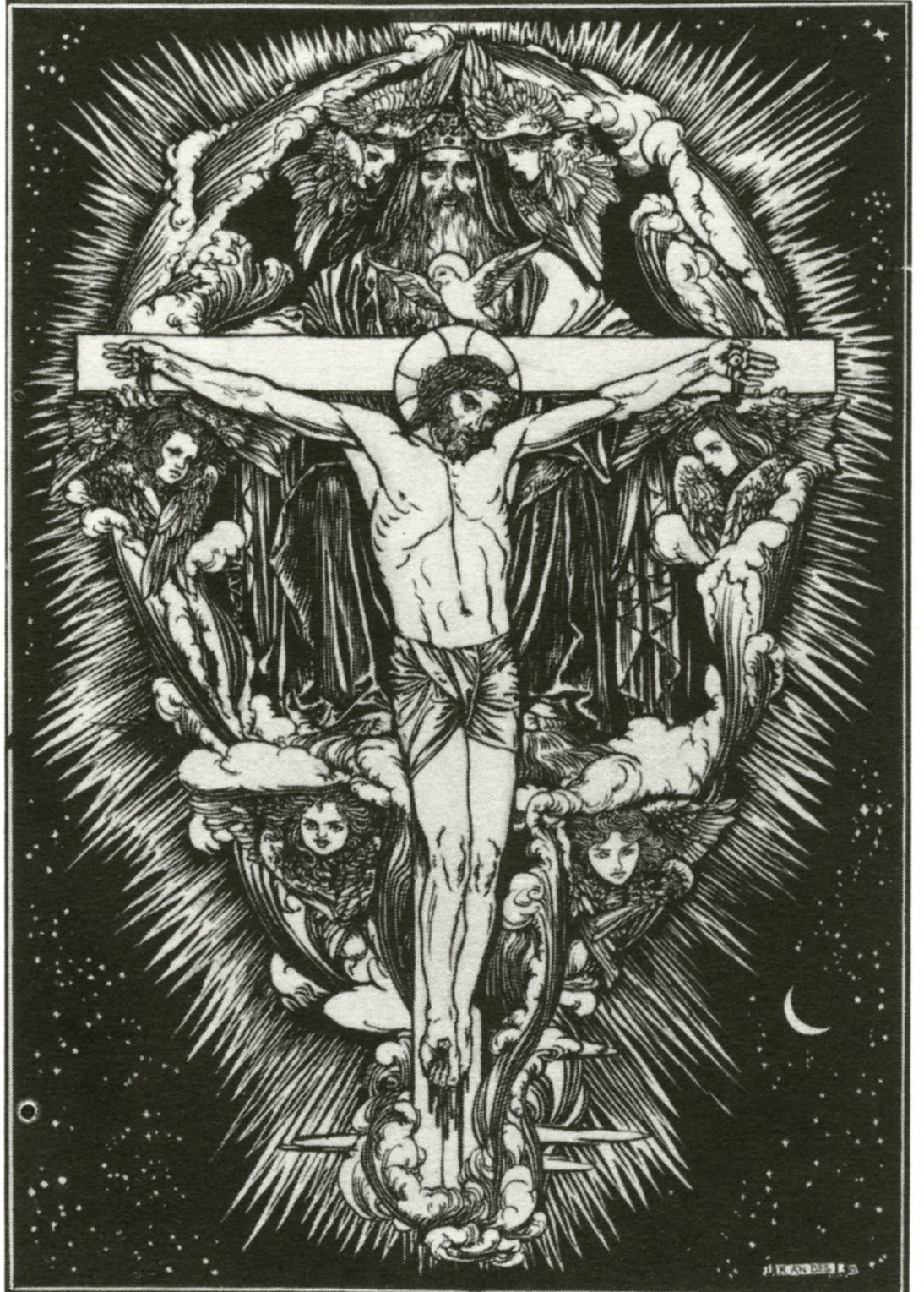

The Trinity and a pen and ink drawing for The Trinity by Robert Anning Bell. Page: 40 x 29.5 cm. Drawing: 22.9 x 16.3 cm. The Altar Book, p. 88. . Collection of John Carter Brown Library at Brown University. This item was catalogue no. 12. in Beckwith, Victorian Bibliomania (1987). Printed presentation page: “John Nicholas Brown from His Affectionate Brother Harold Easter A.D. MDCCCXCVI.” [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Commentary by Alice H. R. H. Beckwith

The Altar Book stands as an example of trans-Atlantic cooperation in design and the religious interrelationship of New England and Britain. North American members of the English Church adopted a standard Book of Common Prayer of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States in 1892, and Daniel Berkeley Updike (1860-1941) was asked to oversee the design of the large paper presentation copies of that first edition. The Altar Book was Updike's second attempt at designing a liturgical book for the Episcopal Church in New England.

Updike descended from the founding family of Wickford, Rhode Island, and his financial backer for The Altar Book and the establishment of his Merrymount Press was Harold Brown (1863-1900), a member of one of Rhode Island's first families. Both men belonged to the Episcopal Church, Updike described their strong ties to England in this way: "Neither Mr. Brown nor I had much in common with American Protestantism, and his position theologically was Tractarian, or as it would now be called, Anglo-Catholic, as mine has continued to be" (Updike, "Notes," 13). Their ties to England extended to printing as well; Updike and Brown knew the works of William Morris's Kelmscott Press, were aware of the magnificent Books of Common Prayer published by William Pickering at Charles Whittingham's Chiswick Press in 1844, and were acquainted with medieval illuminated manuscripts.

Work began on The Altar Book about June 24, 1893. The date is significant as the year when Updike's large-paper edition of The Book of Common Prayer appeared. In his descriptive notes about the first Book of Common Prayer, Updike explained that he was asked to "decorate a book practically already printed." Apparently he had no control over the design of the book as a whole, and this he felt to be a defect that required his graceful explanation tinged with apology in the printed notice circulated with it. Harold Brown came to Updike's aid and allowed him the financial freedom to produce The Altar Book as a visual statement of the values he was not allowed to express fully in the first book project. Writing about The Altar Book, Updike said: "It was largely the dissatisfaction felt with the 'decorated' Prayer Book that suggested the publication of this volume, and Mr. Brown, who was of my way of thinking in such matters, stood ready to back the undertaking. His stipulations were that the book should be as fine a piece of work as I could make it, and that while strictly conforming to the text of those parts of the Book of Common Prayer containing the altar services, it should yet fall in line with missals of an older period" (Updike 17). The results of the Brown-Updike collaboration were spectacular. The Altar Book is a masterpiece of late nineteenth-century printing inspired by medieval precedent.

As designer of The Altar Book, Updike coordinated a group of artists on both sides of the Atlantic, including the American architect and book designer Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue (1869-1924). who created the bindings, borders and initial letters; and British artists Charles William Sherborn (1831-1912), engraver of escutcheons. Sir John Stainer (1840-1912), plainsong composer, and Robert Anning Bell (1863-1933), illustrator. Such collaborations exemplify what John Ruskin called for in his writings earlier in the century (Hauck, "Beaupre Antiphonary," 79). Ruskin's belief that art well done reflected the delight of the artist in his work may have inspired Updike and Brown; in any case, Ruskin's and Morris's writings had been so thoroughly absorbed by 1893 that one could say, with George Parker Winship, that the Englishmen and Updike were of such like minds that they came to similar conclusions.

Such a commonality of attitudes is illustrated by Updike's choice of the maypole and Merrymount as the symbol and name of his press. Merrymount was the estate of Thomas Morton, a Church of England settler who established himself in 1628 near what is today Quincy, Massachusetts. In a series of type specimen samples from the Merrymount Press, Updike explained that Morton believed his Puritan and Pilgrim neighbors were too dour and unhappy, so, hoping to infuse a bit of fun into their daily round, Morton set up a maypole. He was censured by his neighbors. Updike said he hoped the products of the Merrymount Press "will show the good results of work undertaken in somewhat the same spirit" (Winship, "Merrymount," 112-13). Neither Winship nor Updike mentions that the maypole was also symbolic of Mary, and that her month, May, was traditionally celebrated in Roman Catholic countries with dances around a maypole.

Updike planned the symbolism of The Altar Book and concerned himself with the details of each illustration. Shown here are the Trinity page, and a recently discovered pen and ink study for the Trinity by the London illustrator Robert Anning Bell. Letters in the Updike Collection on Books and Printing at the Providence Public Library indicate the drawing was a second version of the subject (Farren, 15). Other letters indicate that Bell had to fit his designs into Goodhue's borders (Findlay, 33-35). The final illustration is set within the floral borders like a medieval miniature on a verso page. Yet the work is not entirely Gothic, because the arrangement of the principal figures recalls Masaccio's Trinity fresco from 1428 in Santa Maria Novella, Florence. Bell did not mention this in his December 10 letter which accompanied the drawing, but he did explain his introduction of a celestial background and clouds stirred by the wind. of the Holy Spirit. In addition. Bell remarked that he included the face of a child from a photograph sent him by Updike. Bell's composition and use of light and dark contrast in the drawing are intense and exciting, but they did not stand out against Goodhue's borders as powerfully as the original version, which Updike eventually decided to use in his book.

References

The Altar Book. Boston: The Merrymount Press, 1896. Printer: Theodore DeVinne. Designer: Daniel Berkeley Updike. Cooperating Artists: Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, Robert Anning Bell, Charles Sherborn, and Sir John Stainer.

Beckwith, Alice H. R. H. Victorian Bibliomania: The Illuminated Book in Nineteenth-century Britain. Exhibition catalogue. Providence. Rhode Island: Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, 1987.

Farren, John. “Daniel Berkeley Updike: Typographical Progression from 1893 to 1930.” Senior thesis, Providence College, 1986.

Hauck, Alice H. R. “Ruskin's Uses of Illuminated Manuscripts and Their Impact on His Theories of Art and Society.” PhD Thesis, The Johns Hopkins University, 1983.

Updike, Daniel Berkeley. “Notes on the Press and Its Work” in Updike: American Printer and His Merrymount Press. Peter Beilenson, ed. New York: American Institute of Graphic Arts, 1947.

Winship, George Parker. “The Merrymount Press in Boston” in Updike: American Printer and His Merrymount Press. Peter Beilenson, ed. New York: American Institute of Graphic Arts, 1947.

Last modified 1 January 2014