This is Ellen Creathorne Clayton's account of Bowers, the opening section (pp. 319-323), of her chapter on female humorists in English Female Artists (1876). It has been formatted for our website, with the addition of headings, links and illustrations, by Jacqueline Banerjee. Full details of the book, and the sources of the illustrations, are given in the bibliography at the end. You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the images and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [ Click on all the images to enlarge them, and for more information about them.]

MONG the attributes specially claimed by Man is a sense of Humour. Woman may be allowed to possess Wit, but except in the case of farce or burlesque actresses, when she is simply parrotizing the fancies of a man, she is denied any perception of Humour.

For the defence it may be urged that Humour is a quality scarcely coveted by the ladies. They like to be admired for wit, archness, piquancy, even sarcasm, or any similar attribute that may be slightly tinged with a soupçon of the comic — but Humour, as a rule, they willingly relegate to those who care to claim it. Wit is fine and elegant: wit shines and scintillates in drawing-rooms and boudoirs, but Humour may run the risk of stepping over the boundary lines of vulgarity. [319/20]

Thus, it may be, arises the otherwise singular fact that so few women have come forward as humorists, though many have been famous for wit or sarcasm.

Mr. Punch's beard is growing white with age, and he has had numerous friends and allies, but in all the years and experiences he has passed through, only one Female Artist has deigned to sun herself in his pages, and not even one lady author has condescended to write as much bs a set of verses for him.

Miss Georgina Bowers is the second lady artist who became known to the world as a designer of comic subjects; for Miss Sheridan, the sister of the Hon. Mrs. Norton, who brought out a comic annual illustrated by herself, can hardly be counted. It will probably be disputed that Miss Bowers is a humorous designer: it may more fairly be said, her designs show rather the finer quality of wit. She rarely quits the company of elegant young beauties, stately dowagers, pompous or jocund bishops, and flirting young curates, lingering in the salon, the boudoir, the garden, the hunting-field, sometimes glancing in for a moment at the stable or kennel, but always in the best of good company. Her chief strength lies, however, in her faithful, spirited portrayal of horses and dogs. She has to a great extent drifted into the "comic line," her own preference being given to animals.

Two illustrations from Bowers's Hollybush Hall. Left: "Tally-Ho!" (Plate VIII). The hunt begins! Right: "The Run of the Season" (Plate XXIII). Maud comes to grief (but not for long!).

Miss Bowers was born in 1836, in London, her [320/21] father — the late Dean of Manchester — being at that time Rector of St Paul's, Covent Garden.

In early childhood, as far back as her recollections extend, Miss Bowers had a great love of country life and amusements. Sport of all description, connected with animals, has had an almost irresistible charm for her. To possess dogs and horses, and make pets of them, has been well-nigh a mania with this young lady; sufficiently so to impress her with the strongest indifference to the languid pleasures of fashionable society.

This passion — it could not be called by any milder name — inspired Miss Bowers with an early taste for drawing animals. This odd and inconvenient fancy was not encouraged by the governesses who successively failed to train her as a drawing-room, sonata-playing miss, and drill her into young ladyism. Books she confesses she "hated" — needlework she "detested." Having no sister of her own age, she was left pretty much to her own resources for amusement When a clever girl is left to find her own recreations, she generally toils at her own particular mania with an intensity of devotion.

At fifteen, Georgina Bowers — whose mother died before she had gained any distinct knowledge of her — was sent away from home into Derbyshire, to some ladies who took private pupils. Here she pined for her dogs and donkeys, and especially one favourite, [321/22] "Old gray Jim," whom she had been in the habit of riding saddleless round the yard at home. Lessons in music, and drawing, and German, and other super-fine accomplishments, could not act as anodynes for this irrepressible yearning, so profited this tiresome pupil little.

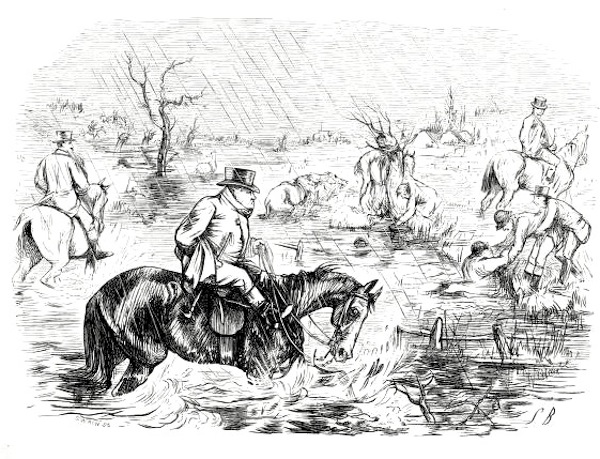

"The Day after a Thaw: Farmer Gripper wishes he could swim home," Plate VIII in Bowers's A Month in the Midlands.

She could not even find refuge in her beloved pencil, for the drawing-master taught nothing but conventional "sketching from nature" in water colours, and discouraged studies of animals. Therefore Miss Bowers had no instruction in the only art for which she cared.

When she "came out," instead of playing her part in society life, she insisted on working at the Manchester School of Art, which helped her a little in her dearly loved pursuit, but hindered her in her social duties. It was difficult to combine the idly busy existence of a votary of Fashion with the drudging student-life of a would-be artist. Yet study she needed, and longed for.

At last she began to draw for Punch. From Mr. Mark Lemon she received much kindness, and later, Mr. Shirley Brooks proved a judicious adviser and helpful friend. But of all her counsellors, perhaps she is most indebted to Mr. Swain, the Punch engraver. Indeed, she considers that she owes grateful thanks for his interest and sympathizing advice.

After the death of John Leech — another generous [322/23] and considerate friend — Miss Bowers determined to strike out a path for herself, and, leaving home, went down to Hertfordshire, taking up her residence there and in Bedfordshire alternately. To have lived in town and worked hard would, perhaps, have advanced her more easily in the way she wished to go; but she could not summon up self-denial sufficient to enable her to give up her hunter and her big dog.

Miss Bowers now designs nearly all the hunting subjects for Punch with slighter sketches, initial letters, and so on; contributing besides to the Graphic, Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, and other publications.

Beginning of Chapter VIII, "Dogs" (D'Avigdor 77).

To her own regret, she finds herself a sketcher when she desired earnestly to take rank in a far higher line of art. But she holds a distinct place of her own. Her horses, her dogs, are inimitable, and full of character. Thoroughly original, fresh and unconventional, her groups, with their surroundings, all bear the impress of the free country life amidst which she lives and works, and which she loves so well.

When not "at work," Miss Bowers fairly lives on horseback. Having a sketch-book which fits into a saddle-pocket, she does all her admirable backgrounds when out riding. She works eight hours a day, and, although only a sketcher, never takes a holiday!

Bibliography

Bowers, Georgina. Hollybush Hall, or, Open house in an Open Country. London: Bradbury, Evans, 1871. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Webster Family Library of Veterinary Medicine. Web. 15 July 2017.

_____. A Month in the Midlands. London: Bradbury, Agnew, 1874. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Webster Family Library of Veterinary Medicine. Web. 15 July 2017.

Clayton, Ellen Creathorne. English Female Artists. London: Tinsley Brothers, 1876. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Web. 15 July 2017.

D'Avigdor, Elim Henry. A Loose Rein. London: Bradbury, Agnew, 1887. Illustrated by Georgina Bowers. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Webster Family Library of Veterinary Medicine. Web. 15 July 2017.

Created 15 July 2017