You Dirty Boy by Faustin Betbeder [August?] 1878, trade card, published by Ramsden, Leeds, and Woodbury, Woodbury Permanent Process, London. Click on images to enlarge them.

This cartoon, You Dirty Boy, is a piece of graphic satire that seems to have escaped wide discussion, despite the prominence in nineteenth-century political history of the two figures it wittily caricatures. The satire aimed here at these politicians lies in the artist’s use of one spectacular phenomenon in late nineteenth-century popular art to criticize their recent political activities.

It is in every sense a “political” cartoon, in the strain of satirical comment on public affairs mainstream in France. For example, on 30 March 1851, as Commune citizens rioted in Paris streets against the new presidency of Louis Napoléon (soon to be Napoléon III), historian Jules Michelet wrote admiringly to the cartoonist Honoré Daumier that his political cartoon “illuminated the whole question better than a thousand newspaper articles” (Osborne 302; Passeron 164). By illuminating issues, cartoons were able to affect them. Michelet continued, “It is through you that the people will be able to speak”.

Ay! There’s the Rub! You Can’t Change the Nature of the Animal” by Thomas Nast. Harper’s Weekly (21 October 1882).

In the United States, Thomas Nast’s slashing cartoons of his political foe, William “Boss” Tweed (of Tammany Hall disrepute), materially swayed voters. As Tweed grumbled, “my constituents don’t know how to read, but they can’t help seeing them damned pictures.” The immediacy of the visual image conveyed the cartoonist’s point directly and more sharply than multiple paragraphs of print. A cartoon’s initial impact had an immediacy for its contemporary viewers lacking for those separated by time from the events depicted. This became particularly true of political cartoons in the nineteenth century, when, thanks to significant advances in technology and print formats, newspapers and magazines flourished as never before, and made “them pictures” available to an increasingly literate public. The concept of immediacy in graphic satire was, and is, vital to the political cartoon. Taylor questions the concept of instant effect in graphic satire but also points out that a cartoon’s full meaning requires its historical context (1-2, 105). In both cases of “You Dirty Boy” the cartoons are so irrevocably attached to their source that they are vital to their analysis. Their impact for contemporary viewers depended on immediate recognition of their subjects and figures. For a modern viewer, however, separated by time from the events and people depicted, a cartoon’s full meaning requires its historical context. And establishing its context reveals the immediacy of its initial impact (Taylor Politics 1-3, 105 and passim).

By 1851, the political cartoon – not (as has often been thought) merely entertaining, ephemeral, or a misuse of art – had already demonstrated its effects in eighteenth-century Britain with the work of James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson, whose offensive, often obscene caricatures of public figures from Napoléon I to George III proved the genre’s capacity to provoke, offend, or destroy its subjects’ characters in its drive to accuse and shame its targets.

But it was in the nineteenth century that printed visual satire had its heyday; in France, cartoonists tested every boundary. Daumier himself was imprisoned in 1831 for lèse majesté against King Louis Philippe. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the political cartoon has spread further, from the print publications in which it still appears to the digital world and social media. It is recognized as a genre in itself, worthy of scholarly attention, that emphasizes how valuable – even essential – it is to our understanding of historical events. Visual satires have the power to illuminate the history that begot them, in images that encapsulate significant moments in time and the hidden layers beneath them. As McPhee and Orenstein point out, from the eighteenth-century caricatures to the editorial cartoons of today, the artist engages with the multiple facets of such moments, commenting – humorously, cynically, or savagely – on current issues, people and their physical and behavioral oddities (all greatly exaggerated), and on social and political wrongs (3; Dickinson 9). Taylor explains that eighteenth-century visual satire, predominantly an art print produced in single sheets, is properly described as “caricature”, while the nineteenth-century “cartoon” applies to one of the multiple images published in the press (Politics 1-3 and passim). The word “caricature” comes from the Italian “caricare,” meaning to charge or even overcharge, “suggestive of the compressed force of expression a cartoon/caricature possesses.” The cartoon is loaded; it contains volumes (Keller 3).

Historians seed their texts with contemporary cartoons for exactly this reason. Similarly, the cartoon addressed here contains far more than the casual observer sees. Its context extends to international geopolitical issues that loomed in the late 1800s, as Russia belligerently challenged Britain’s growing power as empire builder. It also registers the alarmed political and domestic reactions to these issues, while incorporating such varied fields as contemporary fashions, popular art, social fetishes such as the Victorian obsession with cleanliness, and the definitive arrival of modern methods of commercial advertising. All this without explanatory text, something cartoonists often felt, and still feel, obliged to supply in bulk. Therefore, if modern viewers are to read properly this multifaceted cartoon, we need its historical and cultural context.

Without that context, the viewer sees only a woman, aproned, mob-capped and purposeful, vigorously applying the contents of a large basin at her feet to the ears of a disgruntled boy who is stripped to the waist amid the spatters of soap. An everyday domestic scene, Victorian by the clothing, if not for some anomalous details. Bizarrely, the two stand on a raised plinth, rather than on, say, a kitchen or laundry floor. The woman’s face wears an almost demonic grin, with an unservile black ringlet dangling freely over her brow. The boy’s screwed-up features are markedly un -boyish, those of a frowning adult with a receding hairline. As a first helpful step, the cartoonist’s identity can be found (barely visible in this reproduction) in the bottom left-hand corner, the slanting signature of the nineteenth-century artist who signed his work with his Christian name, “Faustin”. An established fact that allows a start to reading this enigmatic image.

Faustin Gabriel Betbeder (1847-1919) was a French multi-talented artist, occasional sculptor, designer and provocateur. His speciality was the cartoon, featuring personages notable -- Victor Hugo (again and again); Queen Victoria and her children -- but mostly political: Cabinet ministers; European royalty; Giuseppe Garibaldi; German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck reduced to a severed head hanging from a guillotine; Napoléon III, given an enema by Wilhelm I, Faut s’Entr’Aider. Ça va aller (Victoria and Albert Museum, London). When a printer refused to sell this, Faustin took charge, published 1,000 copies on credit and eventually 50,000 (McQueen 312fn13). His political caricatures could be quite as brutishly savage as those of his predecessors. He provoked, he offended, he destroyed reputations, he stirred up outrage. His caricatures targeted the French President, Adolphe Thiers, first as an ape, and then as sodomizing Bismarck, Entre Diplomates … Embrassons - nous et tout ça finisse (Victoria and Albert Museum London). He was fined for sketches of Count Cavour, Prime Minister of Italy. Trapped in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), he drew caricatures that lashed the political leaders responsible for the terrible conditions of the infamous Paris siege. In 1870, he quitted France for England, where he started a business “d’impressions en couleurs” (chromolithographs), drew pastoral scenes for publishers, designed for the theatre, married an Englishwoman and settled in London (See below for sources for information about his career). His derisive cartoons, however, continued, with notable softening of tone.

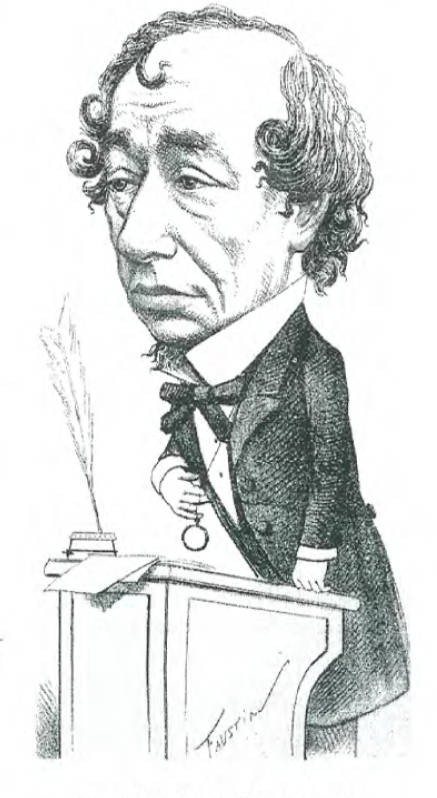

He is probably best known today for Prof Darwin (1874), his visual satire on the theory of evolution, in which Darwin as a hairy ape amiably holds up a mirror to another of the species. That same year he drew caricatures of Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli for the short-lived London Sketchbook (1874-75), for which he drew other politicos, including Disraeli’s enemy, the once and future Prime Minister, William Gladstone. Theirs are the faces in our cartoon. Disraeli, of course, was a favourite target for cartoonists, flamboyant from his hooked nose and cryptic smile to his dyed black curls – dandy, fashionable novelist, MP, leader of the Tory party and finally Prime Minister. Gladstone too was a frequent target, portrayed at odds with Disraeli in virtually every satirical publication, from Punch and Judy to Fun, and editorial cartoonists loved to have them face off against each other in many guises often using parodies of famous works of art.

Left: Professor Darwin by Faustin Gabriel Betbeder. The London Sketchbook. 1874. Right two: Two of Faustin Gabriel Betbeder’s caricatures of Disraeli from theLondon Sketchbook: Rt. Honorable Benjamin Disraeli. “As slippery as the Gordian knot was hard!” (Cymbeline, Act 2, sc. 2). and Rt. Honorable Benjamin Disraeli. First Lord of the Treasury..

Faustin depicted Gladstone as a top-hatted man-about-town, high-collared, bulbous-nosed and invariably frowning. The enmity between the two politicians was real and of many years’ standing. Disraeli was a Tory, Gladstone a Whig. They had risen to become the opposing leaders of their respective parties, while over time their relationship became a cut-and-thrust duel. Dislike turned to hatred, expressed in personal attacks in Parliamentary debates and political meetings. As Chancellor of the Exchequer presenting his 1852 budget, Disraeli scourged his opponents with scorn and insult; in reply, Gladstone censured Disraeli’s bad manners and tore the budget apart, forcing the Tory government to resign. From then on, Disraeli never forgave Gladstone’s appointment as next Chancellor; Gladstone never forgave Disraeli for retaining the robes that went with the office, which still remain at Disraeli’s country mansion, Hughenden (Aldous 70-72, 262-63; Monypenny & Buckle III 442-48; Buckle VI 59; Blake 344-46, 593; Disraeli Letters VI 2492, 2500). The pair became known as the Lion and the Unicorn after John Tenniel’s depiction in Through the Looking Glass (1871).

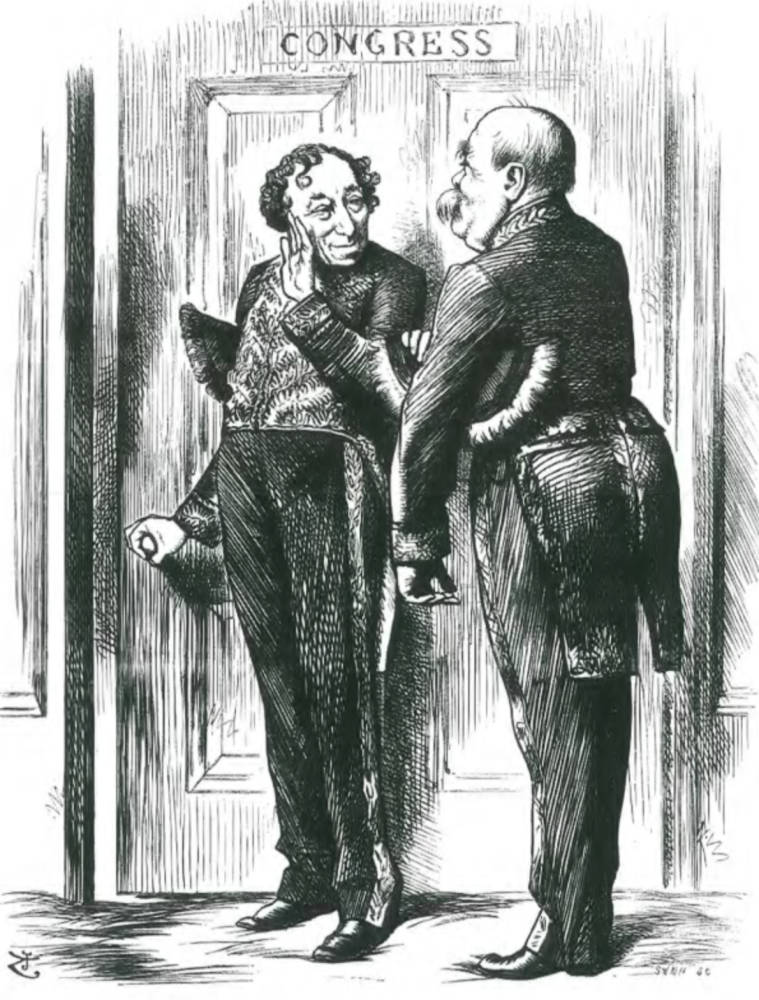

Punch cartoons emphasizing Disraeli’s secretive ways and Gladstone’s dislike of him: Left: Linley Sambourne’s That Fearful Mephistopheles. Right: Tenniel’s Façon de Parler: Lord B. opens door, stops suddenly, and whispers, “O, I say! Bye the Bye! What’s the Word for Compromise?”

And so it went. When in 1875 Disraeli scored a massive coup in acquiring for Britain a major portion of shares in the new Suez Canal, portal to Eastern Europe and India, Gladstone denounced the purchase, particularly the role of Disraeli’s friends the Rothschilds, not only for supplying the required funds of £4 million (a vast sum then) but also for daring to charge interest of 2½ percent (Aldous 262-63). The next year, a crisis in the Balkans and reports of Turkish atrocities against Christians there brought their enmity to a new peak of viciousness. Initially, Disraeli mistakenly dismissed the reports as “coffee-house babble”, but Gladstone took up the Christians’ cause in a pamphlet, Bulgarian Atrocities and the Question of the East, demanding the “extinction” of Turkish power in Bulgaria, and attacking Disraeli as a Jew hostile to Christians, “the worst and most immoral Minister since Castlereagh” (Buckle VI 59; Blake 593; Feuchtwanger 183).

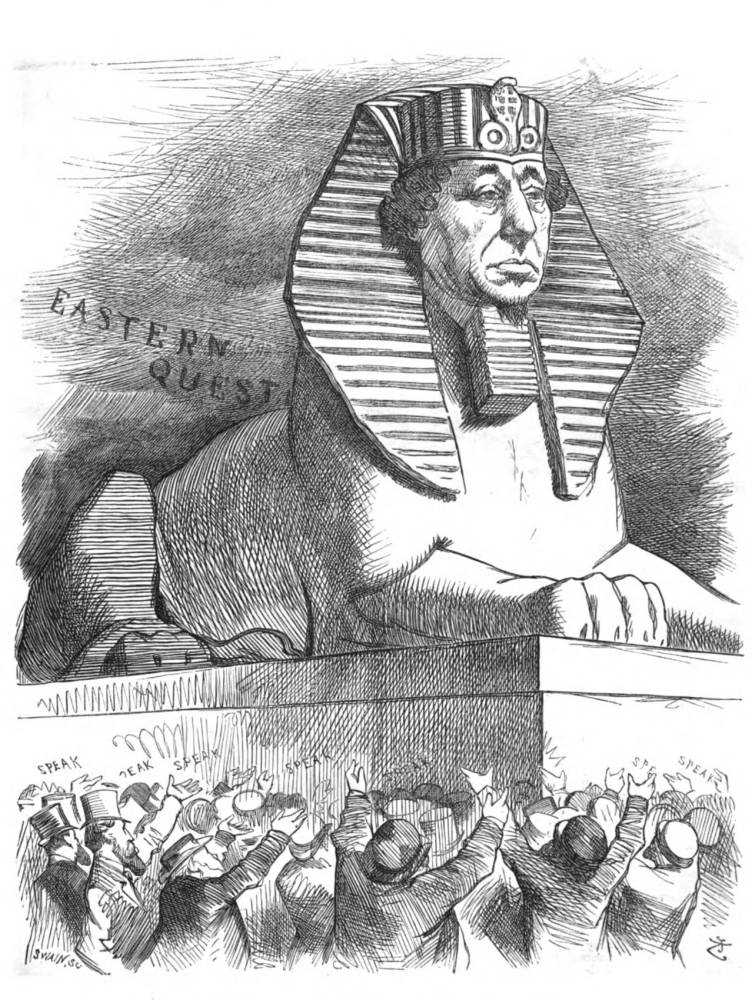

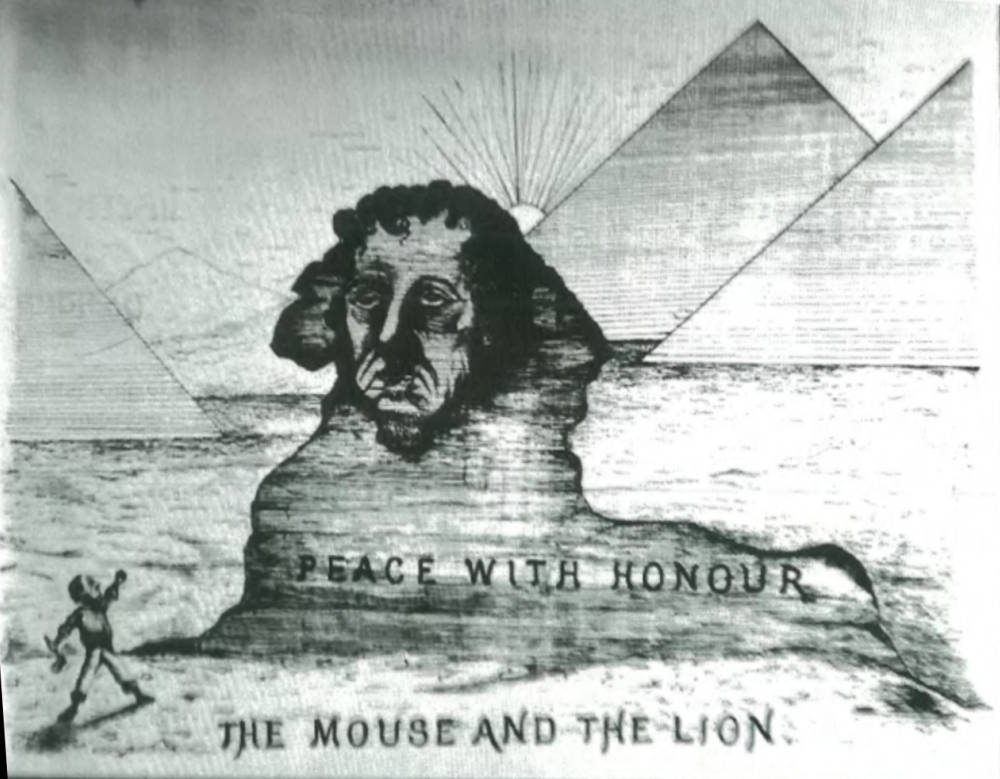

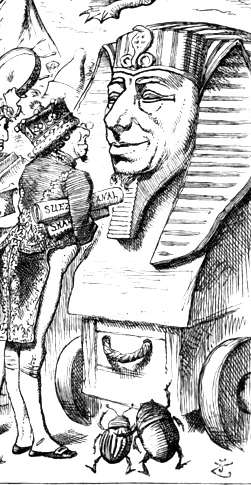

Cartoons emphasizing Disraeli’s secretive ways: Left: The Sphinx is Silent by John Tenniel in Punch. Middle: Peace with Honour, The Mouse and the Lion — Gladstone raged against Disraeli, wielding an axe. Courtesy Wellcome Library, London. Right: A detail from one of the satirical magazine’s opening pages (the entire cartoon):

The hostility continued. In 1878, following a war in which Russia, England’s greatest and most feared rival, defeated Turkey, the Congress of Berlin gave Disraeli an opportunity (which he immediately seized) to stem Russia’s territorial ambitions and strengthen Turkey by personally negotiating with the great powers of Europe. Turkish expansion, it turns out doubly threatened Great Britain, by placing its crucial route to India in danger and by encouraging Afghanistan to take the part of India for itself. Despite poor health, “The Old Man” (as some papers called him) travelled to Berlin, where, during the Congress (12 June-13 July), his conferences with Bismarck and Russian diplomats brought about a Treaty that reset the balance of power by radically shifting European boundaries.

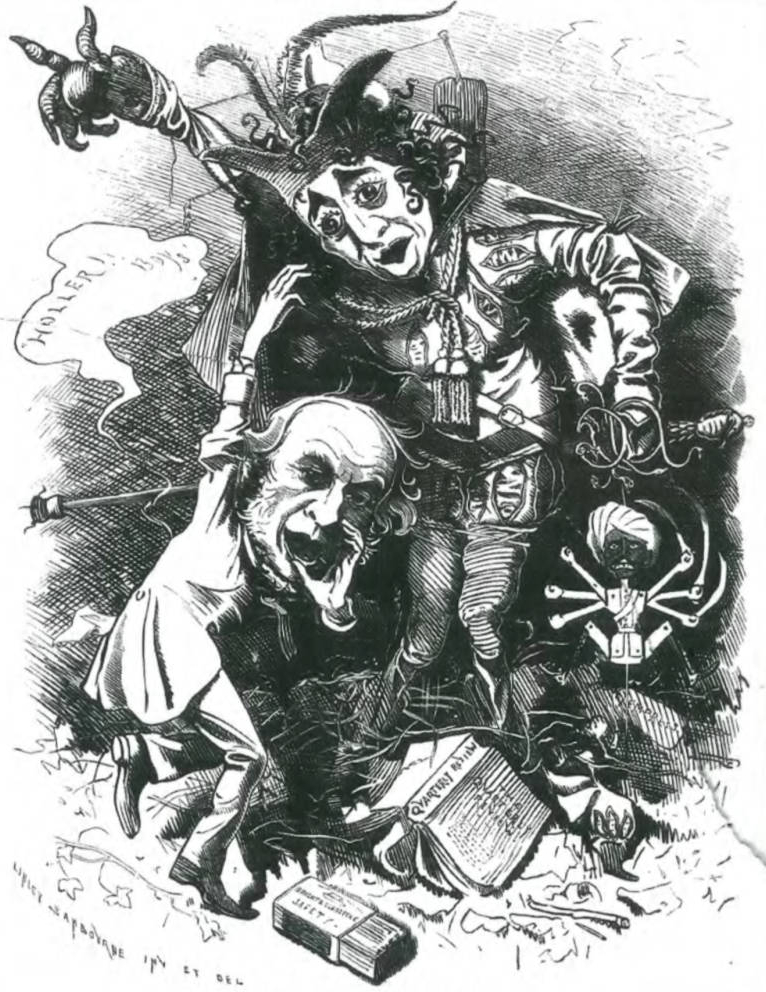

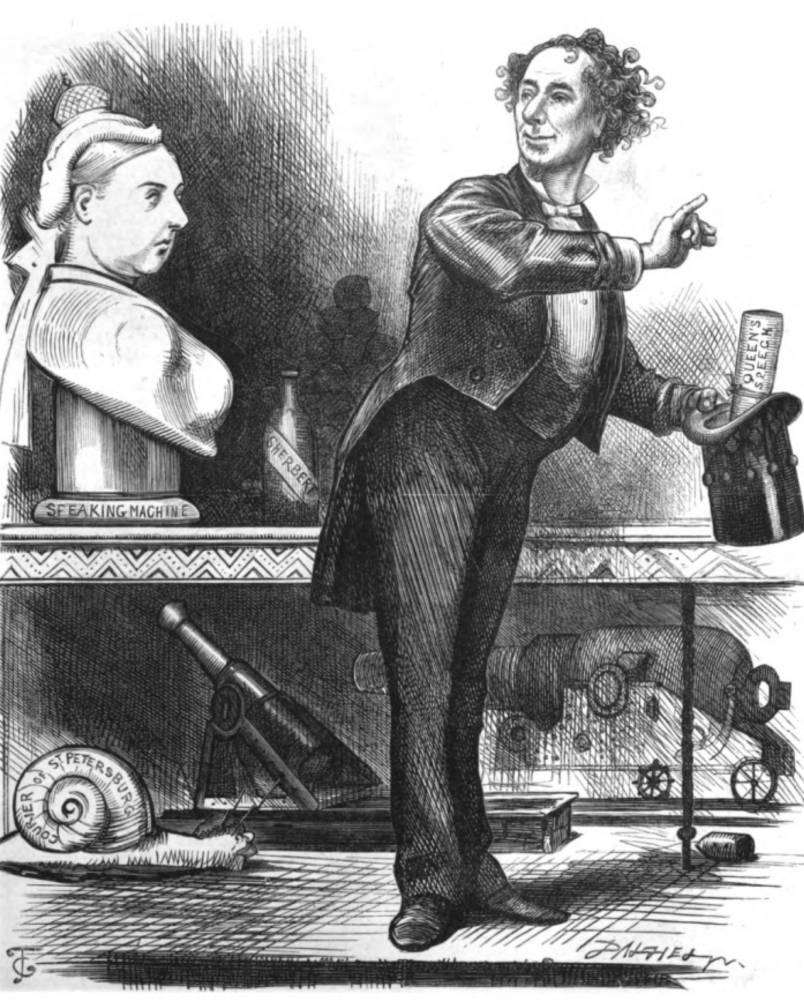

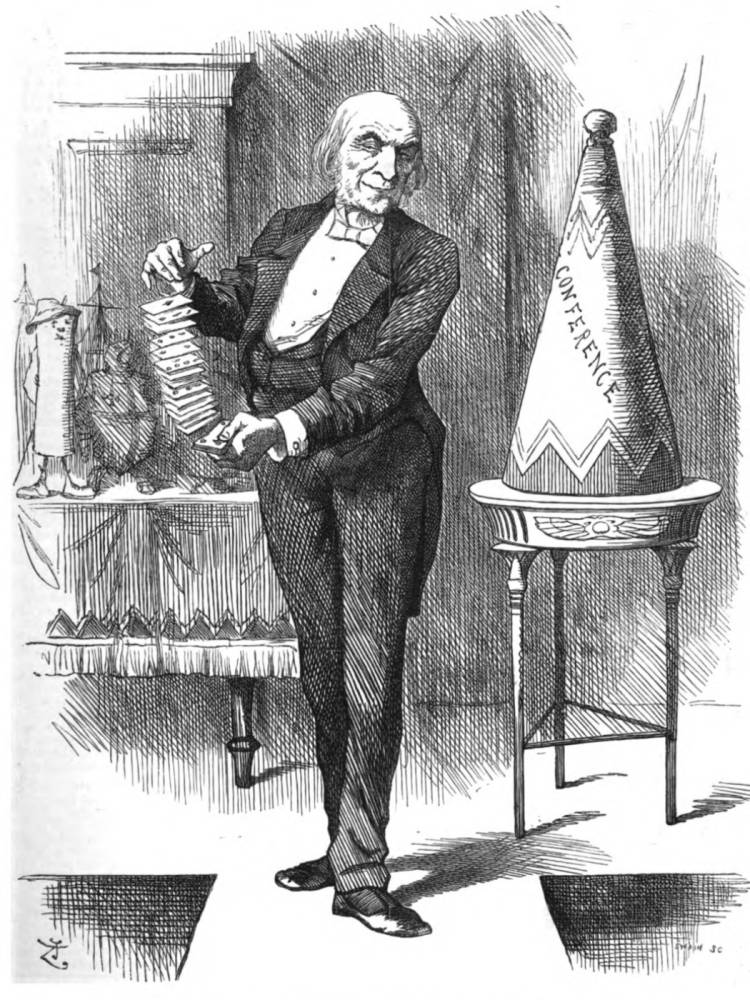

Cartoons criticized both Disraeli at the Berlin Conference and Gladstone later with dealing with similar Egyptian foreign entanglements as dishonest conjurers. Two by John Gordon Thomson in Fun: Left: The Blank Canvas. Middle: The Abode of Mystery. Right: The Westminster Wizard; or, the Downy One of Downing Street. Punch by John Tenniel (5 July 1884).

His efforts not only averted what had seemed inevitable war with Russia, but significantly benefited Britain’s own imperial aspirations, keeping open the sea route to India and the East. (He had proclaimed Victoria Empress of India in the previous year.) The balance he achieved would last for another forty years, until 1914. This second coup outdid even that of the Suez Canal shares. His return to London on 16 July was a personal triumph, loudly cheered by crowds at the docks and the railway station, where he announced to the British populace that he brought “peace with honour”, a phrase Neville Chamberlain would borrow to less effect sixty years later. Reported versions of his words vary - “peace with honour”, “peace in our time” - possibly with changing locales: the docks, the station, even a Downing Street window (Times 17 July 1878; Buckle VI 346; Blake 649). The majority applauded his success; Parliament approved the Treaty; Bismarck, impressed with their confidential talks in Berlin, declared, “Der alte Jude, das ist der Mann” (the old Jew, that is the man). Victoria, who had earlier made him Earl of Beaconsfield and would now reward him with the Order of the Garter, exulted in his achievements. “High and low”, she wrote, ”are delighted, excepting Mr Gladstone, who is frantic” (16 July 1878, quoted Buckle VI 647; Hibbert 364-65. See also Aldous 283-87).

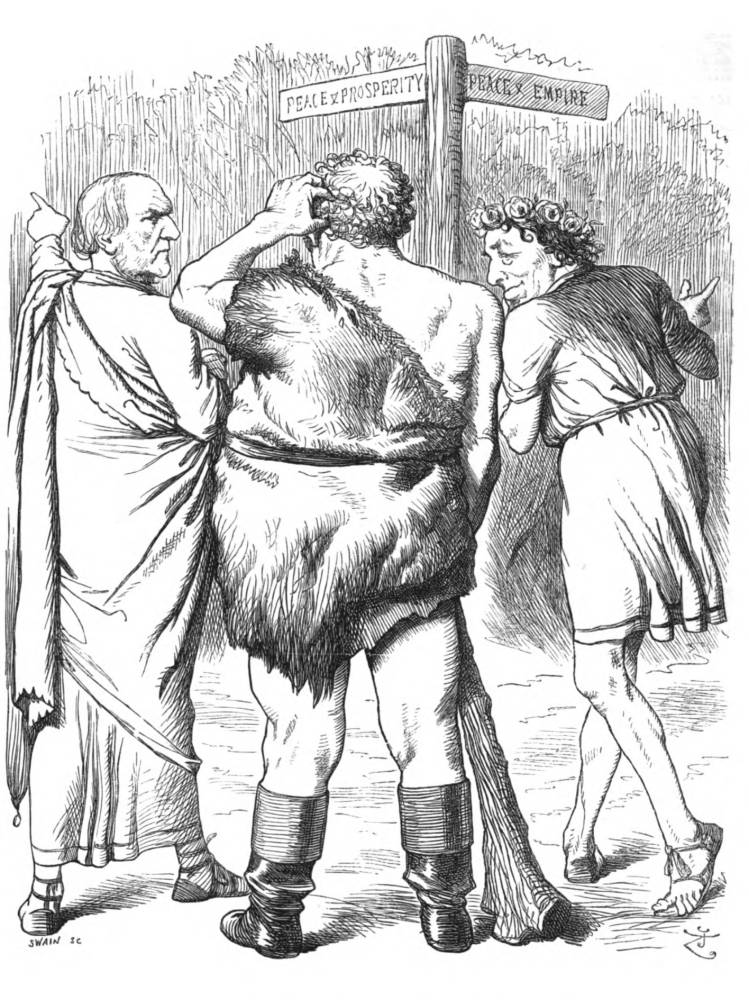

Punch cartoons by John Tenniel emphasizing the rivalry of Disraeli and Gladstone: Left: The Two Augurs. Middle: Performer and Critic. Right: The Choice of Hercules, asking if England choose empire or general prosperity.

Gladstone rejected the triumph. At Oxford in January, he had already broadcast his antipathy, vowed openly to “counterwork” Disraeli’s foreign policy, and dubbed him a “dangerous, devilish character” (Buckle VI 239) . After Berlin, his public attacks became even cruder and more savagely personal, while each politician eviscerated the other. On 21 July, Gladstone loudly condemned as an “act of duplicity” the backstage negotiations with which, he said, Disraeli had fabricated a totally “insane covenant” with Europe (Buckle VI 355 ff.). Disraeli retorted on the 27th that his adversary had maligned him. He himself, he said coolly, was “not pretending to be as competent a judge of insanity” as Gladstone; but then, switching his tone, he denounced him as a “sophistical rhetorician inebriated with his own verbosity”. Incredibly, when Gladstone hit back on the 30th he demanded hard evidence that he had maligned his foe. Disraeli quickly cited the “dangerous, devilish character” sobriquet and the accusation that he had “degraded and debased” the “great name of England.” In distasteful language, Gladstone also decried the “most deadly mischief into which that alien would drag” the country. (So italicized in Weintraub 601). On 1 August, without comment, he recorded in his diary, “read the Fortnightly [Review] on Earl B[eaconsfield]”, an anonymous attack entitled “The Political Adventures of Lord Beaconsfield” (Matthew 334) This, if not written by Gladstone himself, certainly shared his ferocious criticism of Disraeli, a mere “fashionable entertainer … mountebank to the last degree” who had committed his country to a task “not simply difficult and dangerous ... but to obligations which it is impossible to discharge”, a reference to Britain’s future role in maintaining the new boundaries ( Fortnightly Review 24 (Jul-Dec 1878): 250-70). These insulting exchanges became known abroad, to damaging effect. Disraeli dubbing Gladstone a “designing politician”, a “Tartuffe” working for his own “sinister ends”, or Gladstone alleging that Disraeli’s government worked against its own country, produced an international perception that Britain was a divided nation incapable of resisting Russia (Blake 603).

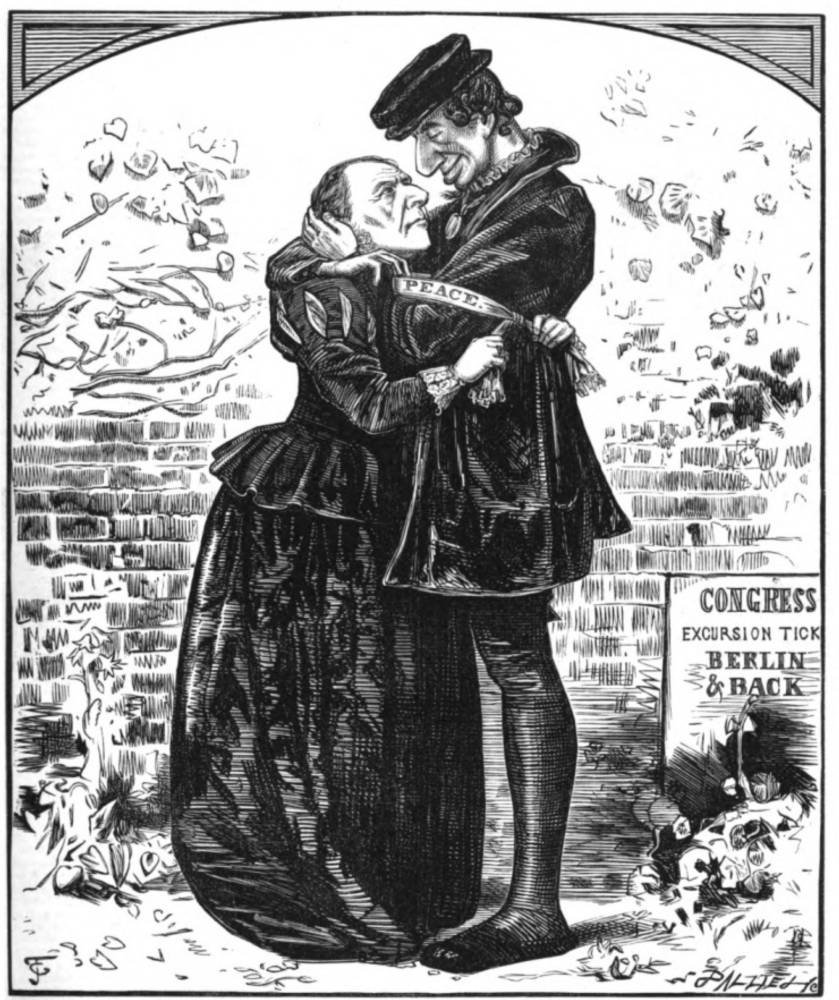

Three cartons by John Gordon Thomson (1841-1911) from Fun: Left: Going to the Congress. Middle: Compliments before parting. Right: The Rival Sandwiches: A Slanging Duet. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Nevertheless, domestic enthusiasm for Disraeli continued to rise; he had, as it were, scrubbed Gladstone’s ears. This background now lets us firmly identify the figures in the cartoon: Faustin knew these faces well, although up till now he had portrayed them as belonging to political aristocrats. Now, in “You Dirty Boy”, Faustin depicts Disraeli as a lowly scrubwoman, while retaining a devilish grin and the black ringlet over his brow. Victoria affectionately recalled his way of saying “‘Dear Madam’ so persuasively as he put his head on one side, his ringlets … falling over his temples” (quoted Hibbert 360). Gladstone becomes a callow urchin, uselessly frowning and caterwauling, restrained only by the woman’s heavy hand. Faustin’s insertion of his subjects’ faces onto other figures was a treatment popular with visual satirists. An instance in a U.S. magazine, The Illustrated American, “Our National Gallery of Sculpture”, uses the “Dirty Boy” figures but attaches faces of American politicians to bodies from classical sculpture. In that version, the woman’s face is different, while the boy’s is that of Republican Joseph G. Cannon, Speaker of the House of Representatives 1903-11. The attached commentary oddly calls the image “pornographic” and therefore unsuitable for young ladies. Perhaps this was text that rightly belongs to other statues in the series: Perseus , or Ajax , who appear in the complete buff, or The Wrestlers, where Republicans James G. Blaine and Thomas Reed are entwined naked in a pose that recalls Faustin’s risqué cartoon of Thiers and Bismarck (Illustrated American [25 October 1890]: 228, 226).

Left: Ay! There’s the Rub!” — You Can't change the Nature of the Animal. Thomas Nast Harper’s Weekly. (21 October 1881): 236. Right: Professor Darwin. The London Sketchbook. 1879.

But why do both Faustin and the Illustrated American use what is, bar the faces, the identical grouping of woman scrubbing boy? The grouping also provides the format of the Nast cartoon. These cartoonists are applying new faces to something so immediate to the public of their time as to be instantly recognizable. This facet of the context derives from the Exposition Universelle de Paris , which took place from May to November 1878, while Gladstone and Disraeli were loudly denigrating each other. The Exposition was huge. It covered more than 66 acres: its many buildings and palaces housed arts, sculptures, new inventions such as an ice machine, a typewriter, Edison’s phonograph, and, not least, the head of the Statue of Liberty. By the time it closed, it had sold tickets to 13 million visitors from all round the world (Illustrated Catalogue of the Paris International Exhibition 1878). Among all these exhibits, there was one that created a huge sensation: a comic statue by Italian sculptor Giovanni Focardi (1842-1903) called “You Dirty Boy”. Public reaction was unprecedented. As one visitor described it, this “uncompromisingly comic statue … set so many hundreds of thousands folks [sic], gentle and simple, screaming with merriment” (Sala I 258-59). And, as befits a statue, it stood on a raised plinth. Here is the inspiration for Faustin’s cartoon.

Left: Faustin Betbeder’s caricature. Middle: Giovanni Focardi’s You Dirty Boy (as sold at Sotheby’s) and the Pear’s Soap advertisement created from it by Thomas J. Barratt. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Focardi’s own inspiration for his statue was banal enough, a glimpse of his landlady, Elizabeth Langley, scrubbing her grimy grandson and saying, “Drat the boy! Will he never come clean?” Opinions differ on the location of the sighting. According to one source, it took place in Preston, Lancashire, while Focardi lived there, but the landlady’s great-great-granddaughter has since counter-claimed that it happened while both Focardi and Langley lived in Thornton Heath, Croydon (Leo H. Grindon, Lancashire: Brief Historical and Descriptive Notes 1892; www.weekly.com/722-you-dirty-boy; Turner 109; 1878 Post Office Directory). At any rate, Focardi’s sculpture immortalised landlady and grandson. The Paris Exposition version was his first, a model in plaster, but the crowds’ enthusiasm was so prevalent that it caught the attention of Thomas J. Barratt, marketing head of the Pears’ Soap company and later considered the “father of modern advertising” for his aggressive methods. The phrase has been attributed to newspaper magnate Lord Northcliffe (Zachary Petit Print Magazine 27 June 2014). Barratt immediately saw the potential for a soap advertisement, telegraphed Focardi and commissioned a marble version for £500 (about $55,000 today). The plaster cast fetched 100 guineas (about £6,000). Later Barratt advertisements would also become famous, as in the famous words: “Good morning! Have you used Pears Soap?”. Celebrities such as Lily Langtry endorsed the soap; Barratt later appropriated John Everett Millais’ well-known painting Bubbles, a desecration that provoked heated disapproval of its use in advertising.

Barratt then vigorously pursued a modern program of saturation, with color posters, placards for shop counters or windows, and enamel signs at railway stations, all stressing the desirability of cleanliness and the purity of his product. Some years later, he presented the statue at the International Health Exhibition of 1884, complete with a medical opinion on the benefits of maintaining healthy skin. He even had magic lantern slides made, to project the Pears’ image of “a mother scrubbing her son” onto the exterior walls of convenient houses (Sweet 44). Photographs of the advertisement were provided for shop windows; smaller (6½ x 10cm) trade cards followed, with or without the Pears lettering. There can seldom have been a more popular statue. Focardi delivered it to Barratt in late 1879, meanwhile selling thousands of terra cotta versions to eager customers worldwide, including Alexandra, Princess of Wales (McQueen 312). In February, before delivery, Focardi had carefully patented it (Franchi 978-94; Chemist and Druggist December 1879), though copyright for the popular cards later reverted to Barratt and to Woodbury and Ramsden publishers. Copies in marble, terra cotta, bronze and stamped metal can still be found today fetching high auction prices. One sold at Sotheby’s in 2008 for $4,750. A website a few years ago listed for sale copies digitally transferred to posters, throw pillows and tote bags. A short film (alas, now lost) was made in 1896, tantalizingly described as “Famous Statue Comes to Life” (www.redbubble.com/people/albutross/works/654290-you-dirty-boy ; IMDb).

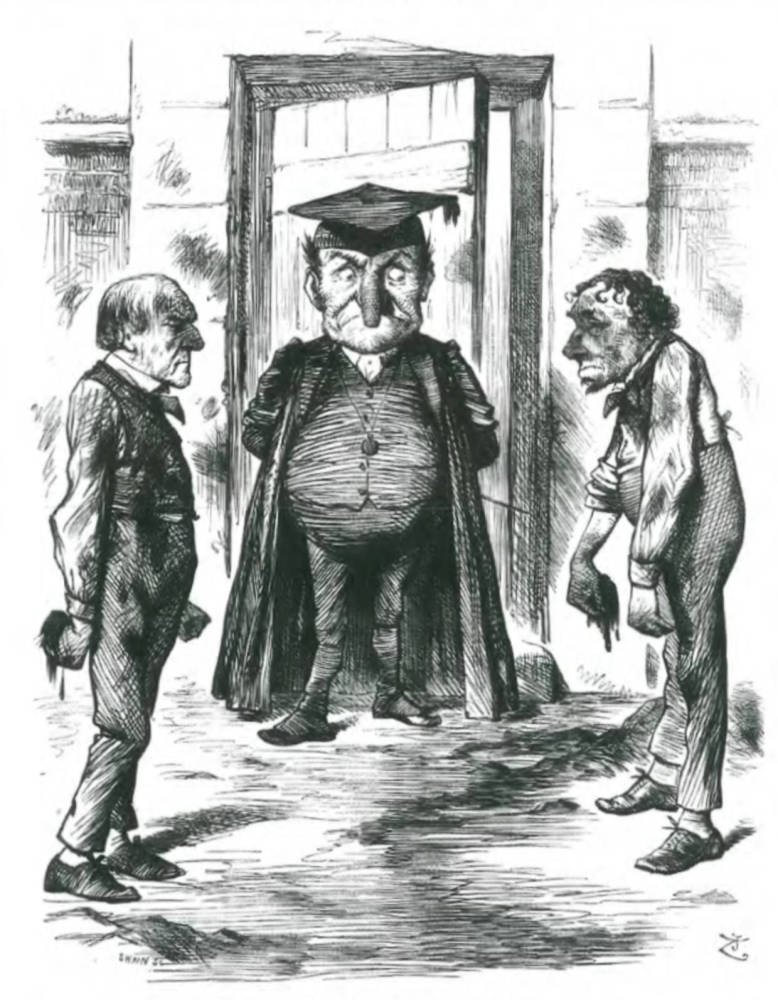

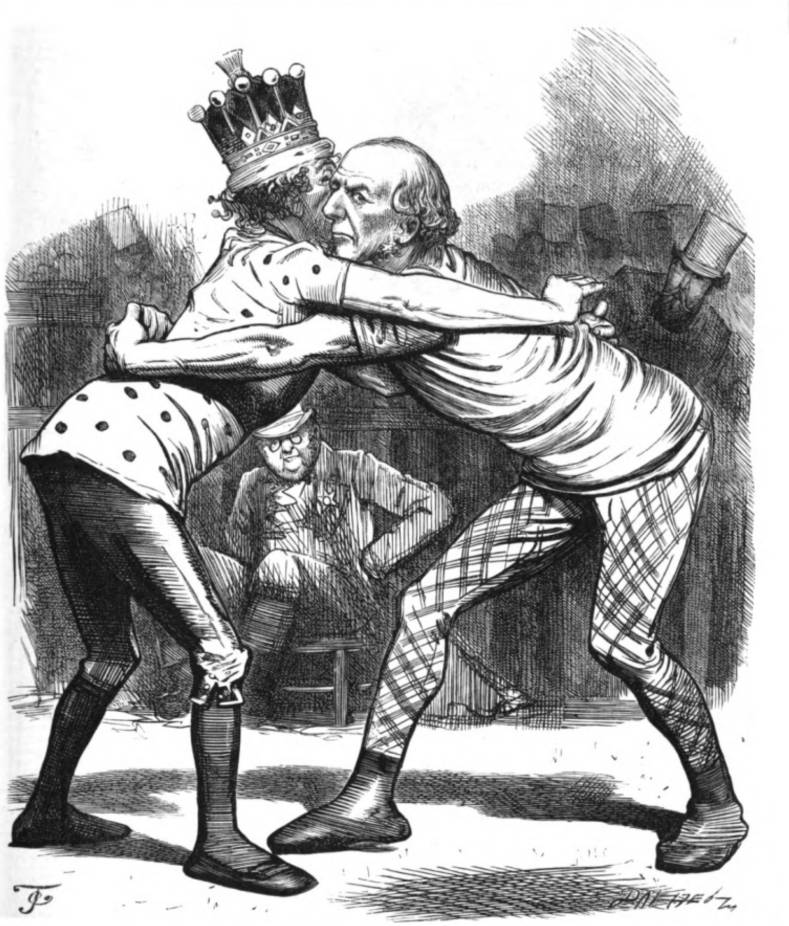

Left: Great National Wrestling Match: The Election Grip. Fun by John Gordon Thomson (31 March 1880). Right: A Bad Example, Mr. Punch dressed as a schoolmaster lectures them, “What’s all this? You, the two head boys of the school, throwing mud! You ought to be ashamed of yourselves!” Punch by John Tenniel (10 August 1878)

Such universal exposure meant that Faustin, Nast and the portrayer of Speaker Cannon could count on immediate recognition of the grouping by the public, readers and viewers who would appreciate the witty commentary on newsworthy people achieved by the superimposed faces. A clue to an approximate dating of Faustin’s cartoon appeared in August 1878, in a Punch cartoon labelled “A Bad Example”, showing Disraeli and Gladstone as extremely dirty schoolboys, with Mr Punch himself as schoolmaster angrily berating: “What’s all this? You, the two Head Boys of the School, throwing Mud! You ought to be ashamed of yourselves!”. In November, Judy comically drew attention to photographs of Faustin’s cartoon displayed in London shop windows: “Monsieur Faustin’s dirty boy is Master William Gladstone, and that is Lord Beaconsfield who is scrubbing him ... [Gladstone] has been throwing mud again, and it has stuck to him. Scrub him hard, scrub him hard, and don’t mind his little tempers” (Judy “Thumbmarks,” 27 November 1878 222) Both cartoons and comments indicate the public’s full awareness of the point in Faustin’s cartoon. Like Focardi’s statue and the image’s surface, it is comic – Disraeli as stern landlady holding down Gladstone as whining urchin – but there is yet another layer: it is reductive. In the Illustrated American, the vast contrast between the classical statues and the present-day politicians severely reduces the politicians. The Nast cartoon is similarly reductive: Governor Cleveland as determined grandmother scrubs corruption off Tweed, the Democratic tiger, though Nast obviously felt his cartoon needed numerous pieces of explanatory text. Taylor discusses the reductive force of the political cartoon in “Cartoon Politics: the literary ghosts of elections past and present”. The Conversation 21 April 2015.

With its context, the full subversive quality of the Faustin cartoon can be seen. In art as in life, neither figure wins. The artist’s visual image is a downmarket satire on both Gladstone and Disraeli, its figures a far cry from Gladstone as “Grand Old Man” or Disraeli as Knight of the Garter. Faustin reminds his public that the exchanges between them are, at the least, undignified, unworthy of their positions in the government of the country, but possibly also deleterious, domestically divisive and internationally begriming Britain’s status in Europe. These two prominent men should, as Punch thinks, be acting as befits Head Boys: running the school, not slinging mud at one another. Like the best political cartoons, this one is packed; it contains volumes, and its ultimate meaning goes much deeper than a comic sketch. And Faustin achieves it without a single word of text.

Sources for Information about Faustin’s Career

“Faustin Betbeder”, Wikipédie; Bulletin de la Société archéologique, historique et scientifique de Soissons Bibliothèque Nationale de France; Civil Registration of Marriages England 1873; Census of England and Wales 1881, 1901, 1911; Index of Deaths England 17 July 1919; “Londres pittoresque: album par Faustin.” Bodleian Library, Oxford; “April Showers Bring May Flowers,” MissJaneblog.blogspot.com (2014).

Bibliography

Aldous, Richard. The Lion and the Unicorn: Gladstone vs Disraeli. London, 2006.

Betbeder, Faustin Gabriel. Londres pittoresque: album par Faustin. Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Blake, Robert. Disraeli. New York, 1967.

Buckle, G.E. The Life of Benjamin Disraeli Earl of Beaconsfield VI 1876-1881. London, 1920.

Bulletin de la Société archéologique, historique et scientifique de Soissons. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1862.

Dickinson, H.T. Caricatures and the Constitution 1760-1832. Cambridge, 1986.

Disraeli, Benjamin. Letters [BDL], VI 1852-1856. Ed. M.G. Wiebe, Mary S. Millar, Ann P. Robson. Toronto, 1997.

Feuchtwanger, Edgar. Disraeli. London, 2000.

Flint, Kate. Victorians and the Visual Imagination. Cambridge, 2000.

Franchi, Allessandro. “A Rebellious Artist” XXth Century II. 1903.

Grindon, Leo H. Lancashire: Brief Historical and Descriptive Notes. 1892.

Harper’s Weekly . 21 October 1882.

Hibbert, Christopher. Queen Victoria: A Personal History. London, 2000.

The Illustrated American. (Oct-Dec 1890). Hathi Trust Digital Library. Web.

Illustrated Catalogue of the Paris International Exhibition 1878. London, 1878.

Illustrated London News. (2 August 1884): f6

Judy, or the London Serio-Comic Journal. 27 November 1878.

Keller, Morton. The Art and Politics of Thomas Nast. Oxford, 1968.

The London Sketchbook. 1874.

McPhee, Constance, and Nadine M. Orenstein. Infinite Jest: Caricature and Satire from Leonardo to Levine. New York, 2011.

McQueen, Alison. Empress Eugénie and the Arts. London, 2011.

Gladstone, William E. Diaries of William Gladstone. Ed. H.C.G. Matthew. 1868-94 IX. Oxford 1986.

Monypenny, William Flavelle, and Buckle, George Earle. Life of Disraeli III. London, 1914.

Osborne, Harold, ed. Oxford Companion to Art. Oxford, 1970.

Passeron, Roger. Daumier. New York, 1981.

Punch, or The London Charivari. 1878.

Sala, G.A. Paris Herself Again in 1878-9. London, 1879.

Sweet, Matthew. Inventing the Victorians. London, 2002.

Taylor, David Francis. “Cartoon Politics: The literary ghosts of elections past and present”. The Conversation. 21 April 2015);

Taylor, David Francis. The Politics of Parody: A Literary History of Caricature, 1760-1830. Yale, 2018.

Turner, E.S. The Shocking History of Advertising. London, 1952.

Weintraub, Stanley. Disraeli: A Biography. New York, 1993.

Last modified 24 July 2022