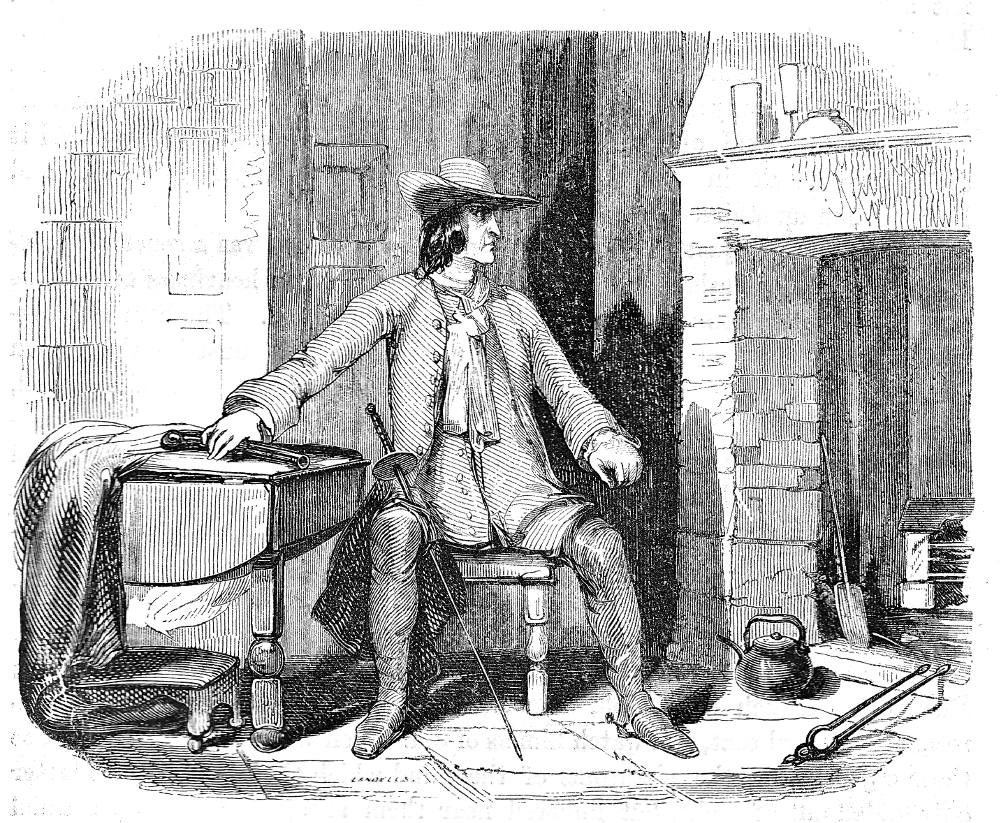

Mr. Haredale's Lonely Watch by George Cattermole. 3 ⅝ x 4 ½ inches (9.3 cm by 11.5 cm). Vignetted, wood-engraved. Tailpiece for Chapter XLII, Barnaby Rudge. 10 July 1841 in serial publication (fortieth plate in the series). Part 22 in the novel, serialised in Master Humphrey's Clock, Vol. III (part 66), 180. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated: Mr. Haredale bent on solving a Mystery

"But this is a dull place, sir," said Gabriel lingering; "may no one share your watch?"

He shook his head, and so plainly evinced his wish to be alone, that Gabriel could say no more. In another moment the locksmith was standing in the street, whence he could see that the light once more travelled upstairs, and soon returning to the room below, shone brightly through the chinks of the shutters.

If ever man were sorely puzzled and perplexed, the locksmith was, that night. Even when snugly seated by his own fireside, with Mrs Varden opposite in a nightcap and night-jacket, and Dolly beside him (in a most distracting dishabille) curling her hair, and smiling as if she had never cried in all her life and never could — even then, with Toby at his elbow and his pipe in his mouth, and Miggs (but that perhaps was not much) falling asleep in the background, he could not quite discard his wonder and uneasiness. So in his dreams — still there was Mr Haredale, haggard and careworn, listening in the solitary house to every sound that stirred, with the taper shining through the chinks until the day should turn it pale and end his lonely watching. [Chapter the Forty-second, 180]

Commentary: Portraiture plus Suspense

It has been five years since Mary Rudge decided to go into hiding, to avoid being blackmailed by her estranged husband. She had renounced her widow's pension from the Haredale family so that Old Rudge would have no tangible motive for extorting her, but she was still apprehensive about her ex-husband's threats against Barnaby. For five years the house provided her by Geoffrey Haredale has remained uninhabited, and signs of decay and neglect are everywhere as Gabriel Varden and Haredale search the vacant building, trying to ascertain what became of Barnaby and his mother. Cattermole shows us Varden's parting view of the Catholic nobleman as he turns to go home.

On the evening of the day on which the East London Volunteers have held their annual military exercises, and "Serjeant" Varden returns home to find that his family have gone out (likely to a meeting of the Protestant Association) and that Haredale is waiting for him in a Hackney cab. Over the course of their ride to the Rudges' in Southwark, Hardeale closely interrogates the locksmith about the mysterious old ruffian who appeared five years before at The Maypole and apparently assaulted Edward Chester in town; Haredale seems determined to solve the mystery of this highwayman's identity, and the reader suspects that Haredale knows that Old Rudge is that enigmatic traveller — and that Old Rudge killed his brother. Cattermole takes his cue from Dickens in describing the pensive, resolute figure of the self-appointed detective who has determined to spend whole nights in the deserted Southwark house:

With that, as if to change the theme, he led the astounded locksmith back to the night of the Maypole highwayman, to the robbery of Edward Chester, to the reappearance of the man at Mrs. Rudge’s house, and to all the strange circumstances which afterwards occurred. He even asked him carelessly about the man’s height, his face, his figure, whether he was like any one he had ever seen—like Hugh, for instance, or any man he had known at any time—and put many questions of that sort, which the locksmith, considering them as mere devices to engage his attention and prevent his expressing the astonishment he felt, answered pretty much at random.

At length, they arrived at the corner of the street in which the house stood, where Mr. Haredale, alighting, dismissed the coach. "If you desire to see me safely lodged," he said, turning to the locksmith with a gloomy smile, "you can." [XLII, 178-79]

However, the pistols and the sword are not merely lying on the table; rather, Haredale reaches for one of the pistols and has the sword at the ready, as if he has detected some sound indicative of a nocturnal visitor. Thus, the illustrator heightens the suspense of the text as he leads readers to expect a confrontation between Haredale and Old Rudge. Cattermole has captured the determination but not the haunted quality of his subject in the portrait of Geoffrey Haredale:

Here Mr. Haredale struck a light, and kindled a pocket taper he had brought with him for the purpose. It was then, when the flame was full upon him, that the locksmith saw for the first time how haggard, pale, and changed he looked; how worn and thin he was; how perfectly his whole appearance coincided with all that he had said so strangely as they rode along. It was not an unnatural impulse in Gabriel, after what he had heard, to note curiously the expression of his eyes. [179]

Related Material including Other Illustrated Editions of Barnaby Rudge

- Dickens's Barnaby Rudge (homepage)

- George Cattermole, 1800-1868; A Brief Biography

- Phiz's Original Serial Illustrations (1841)

- Cattermole and Phiz: The First Illustrators — A Team Effort by "The Clock Works" (1841)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley's six illustrations (1865 and 1888)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition illustrations (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 46 illustrations for the Household Edition (1874)

- A. H. Buckland's 6 illustrations for the Collins' Clear-type Pocket Edition (1900)

- Harry Furniss's 28 illustrations for The Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Barnaby Rudge. Illustrated by Hablot K. Browne ('Phiz') and George Cattermole. London: Chapman and Hall, 1841; rpt., Bradbury & Evans, 1849.

________. Barnaby Rudge — A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. VII.

Hammerton, J. A. "Ch. XIV. Barnaby Rudge." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition, illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. 213-55.

Vann, J. Don. "Barnaby Rudge in Master Humphrey's Clock, 13 February 1841-27 November 1841." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. 65-6.

Created 4 January 2006

Last modified 15 December 2020