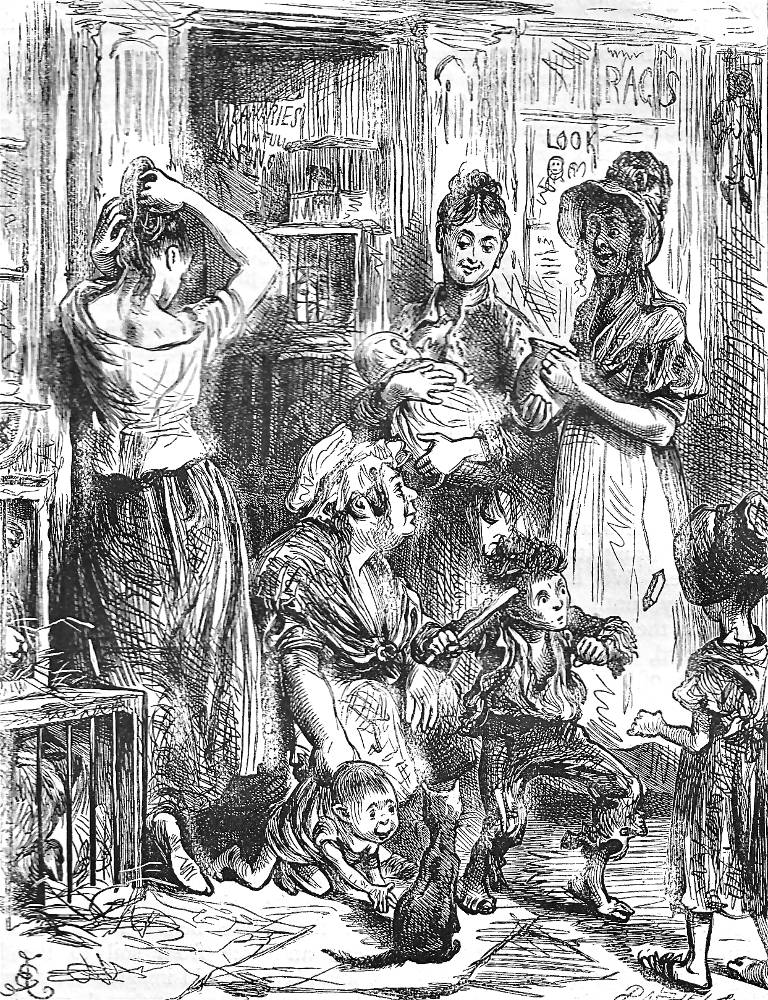

Meditations in Monmouth Street (half-page vignette) by George Cruikshank. Copper-engraving (1836): 8.5 cm high by 8.3 cm wide (3 ⅜ by 3 ⅛ inches), vignetted, facing p. 97. Steel-engraving (1839): 12 by 9.9 cm wide (4 ½ by 3 ¾ inches), vignetted, facing p. 54. In re-engraving the 1836 copper-plate Cruikshank enlarged the gutter in the foreground, and added the word "Monmouth" to the street sign, upper left. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: A Dreary Used-Clothing Street

We have always entertained a particular attachment towards Monmouth Street, as the only true and real emporium for second-hand wearing apparel. Monmouth Street is venerable from its antiquity, and respectable from its usefulness. Holywell Street we despise; the red-headed and red-whiskered Jews who forcibly haul you into their squalid houses, and thrust you into a suit of clothes, whether you will or not, we detest.

The inhabitants of Monmouth Street are a distinct class; a peaceable and retiring race, who immure themselves for the most part in deep cellars, or small back parlours, and who seldom come forth into the world, except in the dusk and coolness of the evening, when they may be seen seated, in chairs on the pavement, smoking their pipes, or watching the gambols of their engaging children as they revel in the gutter, a happy troop of infantine scavengers. Their countenances bear a thoughtful and a dirty cast, certain indications of their love of traffic; and their habitations are distinguished by that disregard of outward appearance and neglect of personal comfort, so common among people who are constantly immersed in profound speculations, and deeply engaged in sedentary pursuits.

We have hinted at the antiquity of our favourite spot. "A Monmouth-street laced coat" was a by-word a century ago; and still we find Monmouth-street the same. Pilot great-coats with wooden buttons, have usurped the place of the ponderous laced coats with full skirts; embroidered waistcoats with large flaps, have yielded to double-breasted checks with roll-collars; and three-cornered hats of quaint appearance, have given place to the low crowns and broad brims of the coachman school; but it is the times that have changed, not Monmouth-street. Through every alteration and every change, Monmouth Street has still remained the burial-place of the fashions; and such, to judge from all present appearances, it will remain until there are no more fashions to bury. ["Scenes," Chapter 6, "Meditations in Monmouth Street," pp. 34-35 in the 1839 edition; pp. 95-97]

Commentary

Originally published in the Morning Chronicle (September 24, 1836) as "Sketches by Boz, New Series No. 1." At the second-hand clothing shops in Monmouth Street, "the burial-place of the fashions," Boz imagines the former owners of the clothes and shoes that are for sale. In particular he constructs the life story from boyhood to death of one man whose lifetime of suits are hanging together in one of the shops.[Davis, 240]

One cannot simply walk down Monmouth Street in present-day London and see the very buildings that Dickens described in 1836 because it was subsumed into the newly designed Shaftesbury Avenue by architect George Vulliamy and urban civil engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette between 1877 and 1886 to speed arterial traffic through St. Giles and Soho, an urban renewal project designed to clear away the lawless, unsanitary slums, and dislocate the working poor who had lived there for generations:

The first Monmouth Street ran approximately where the middle stretch of Shaftesbury Avenue now is (until it was obliterated by the controversial Metropolitan Board of Works renovations in the late 19th Century). The current Monmouth Street has existed for many years, it was formerly called Little and Great St Andrew’s Streets and only took its current name in 1930.

As a scion to the clothing trade, around 1840 there sprung up a number of cobblers on Monmouth Street. Boots and shoes were bought, sold and repaired here, although much of the 'cobbling' was just brown paper and blacking. Around this time, "Monmouth Street finery" was a common phrase used as a euphemism for tat. ["In and Around Covent Garden"]

Although the descriptions of various shops in the nearby Seven Dials are not strictly speaking part of Dickens's description of the group of women gosipping on the stoop, in the Household Edition illustration of 1874 Now anybody who passed through the Dials on a hot summer's evening, and saw the different women of the house gossiping on the steps, would be apt to think that all was harmony among them, and that a more primitive set of people than the native Diallers could not be imagined. Fred Barnard has inserted signage for "Canaries" and "Rags" to suggest that the multi-generation household occupies a building partly given over to commercial activity of a sordid variety that are aspects of what we today term "recycling" as rags were employed in paper-making and bones in china manufacture. Although surely as much a residential as well as a business area, Monmouth Street in Cruikshank's 1839 illustration Sfocuses as much on the three families as it does on the three businesses: P. Patch (second-hand clothing, centre), the boot and shoe shop (right, but displaying two women's dresses and a large bonnet), and a used hat-shop (left) run by two Jewish entrepreneurs, "Moses & Levy" (the second-hand clothing trade being a niche in the 19th century British economy dominated by Jewish families). Under the watchful eyes of three mothers and three fathers, scruffy boys and little girls in frocks play and explore the world in the stream of the kennel, communally floating a toy boat and fishing as if they were denizens of the Upper Thames. While the men desultorily smoke long-stemmed pipes, the young women tend infants and (presumably) assist in the administration of these "family businesses" in the graveyard of old clothes, in which children play happily, blissfully unaware of the revenants of past lives hanging up behind them.

Hogarth was also highly influential on Dickens in formal terms. His Progress paintings and their wide dissemination as prints provided Dickens with models for constructing a narrative as a sequence of significant scenes, especially in cautionary fables. One early example can be seen in "Meditations in Monmouth Street." In this sketch, Boz puts an imaginary inhabitant into a second-hand suit of boy's clothes and fancies he can trace the growth and development of that boy, stage by stage through other sets of second-hand clothes, into a delinquent man and eventually into a hardened criminal. The sequence is strongly visualized as if a succession of scenes were literally being paraded before Boz: "We knew at once, as anybody would, who glanced at that broad-skirted green coat, with the large metal buttons . . . We saw the bare and miserable room . . . crowded with his wife and children, pale, hungry and emaciated; the man . . . staggering to the tap-room” (Sketches by Boz 100–1). The tableauesque format of the narrative, the attention to telling small details, and the over-arching didactic agenda all derive from Hogarth and from Hogarth’s descendants in that graphic tradition. [Malcolm Andrews, Ch. 7, p. 13]

Relevant Illustrations from The Household and Charles Dickens Library Editions

Left: Fred Barnard's more benign and charming view of urban poverty, Now anybody who passed through the Dials on a hot summer's evening, and saw the different women of the house gossiping on the steps, would be apt to think that all was harmony among them, and that a more primitive set of people than the native Diallers could not be imagined — a picture situated in the midst of the sixth chapter rather than the fifth. Right: Harry Furniss's realisation of Dickens's reverie about dancing boots and shoes outside the shops on Monmouth Street, Meditations in Monmouth Street. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Dudley Street, Seven Dials by French social realist Gustave Doré — a busy street scene with sets of shops which can be seen on the right. The shops are selling shoes which are lining up on the floor around the opening from under the ground. Children and their mothers are in front of them. This image was first published in Blanchard Jerrold's London: A Pilgrimage (1872), on p. 158. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned images, formatting and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Andrews, Malcolm. "Illustrations." University of Kent. Web. Accessed 30 April 2017.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Chapter Seven, "Meditations in Monmouth-Street." Sketches by Boz. Second series. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: John Macrone, 1836. Pp. 93-112.

Dickens, Charles. "Meditations in Monmouth Street," Chapter 6 in "Scenes," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 54-59.

Dickens, Charles. "Meditations in Monmouth Street," Chapter 6 in "Scenes," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Pp. 34-38.

Dickens, Charles. "Meditations in Monmouth Street," Chapter 6 in "Scenes," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 1. Pp. 70-76.

Dickens, Charles, and Fred Barnard. The Dickens Souvenir Book. London: Chapman & Hall, 1912.

Hawksley, Lucinda Dickens. Chapter 3, "Sketches by Boz." Dickens Bicentenary 1812-2012: Charles Dickens. San Rafael, California: Insight, 2011. Pp. 12-15.

"In and Around Covent Garden." Web. Accessed 23 April 2017.

Jerrold, William Blanchard. London: A Pilgrimage. Illustrated by Gustav Doré. London: Grant & Co., 1872.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Created 26 April 2017 last updated 17 May 2023