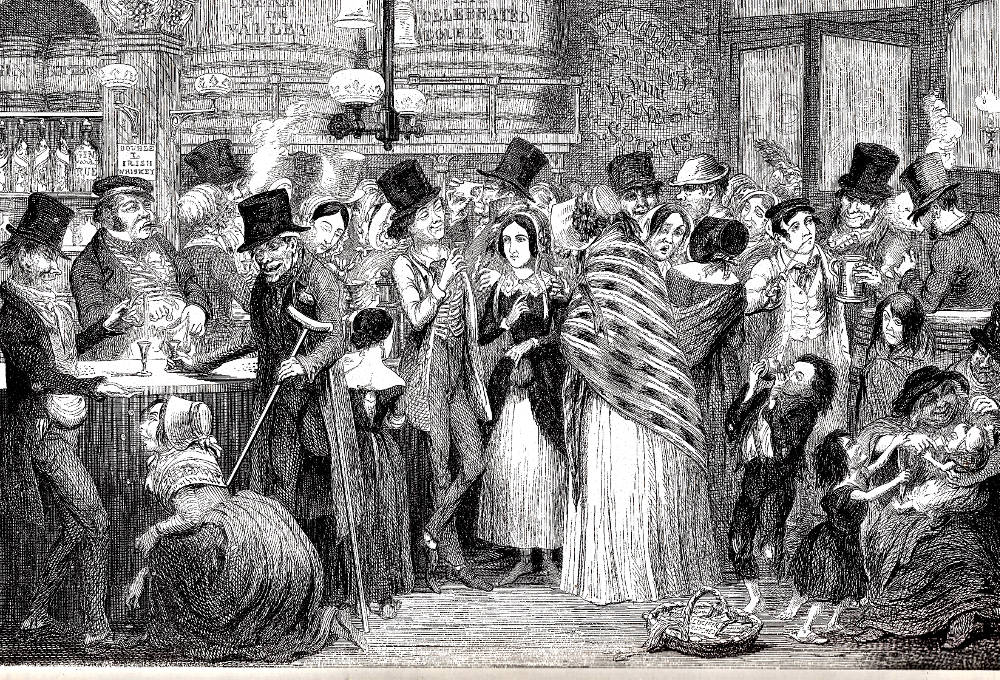

Neglected by Their Parents, Educated Only in the Streets and Falling into the Hands of Wretches Who Live Upon The Vices of Others, They Are Led to the Gin Shop, to Drink at That Fountain Which Nourishes Every Species of Crime. — George Cruikshank. 1848. First illustration in The Drunkard's Children. Folio page: 46 x 36 cm (24 inches by 14.5 inches), framed. The etchings were reproduced by glyphography, "enabling the publisher [David Bogue, London] to sell the entire series for one shilling" (Vogler, p. 159). "This suite appeared in similar size and editions to that of The Bottle, but it was never reissued in smaller format" (Vogler, p. 161), except that throughout this sequel the majority of the scenes are not individually signed. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Drunkard's Children: An Introduction

In the concluding plate of the previous series, The Bottle Has Done Its Work — It Has Destroyed the Infant and the Mother, It Has Brought the Son and the Daughter to Vice and to the Streets, and Has Left the Father a Hopeless Maniac (1847), Cruikshank had anticipated the trajectory of the sequel, from the adolescent son and daughter's visiting their crazed father in the asylum for the criminally insane through to consorting and carousing with criminal types in the first three scenes of The Drunkard's Children, continuing the downward spiral of the gin bottle to the utter destruction of the next generation. As inevitable as the father's gin-madness and the mother's murder are the son's being transported and the daughter's drowning herself in the Thames after becoming a prostitute. Perhaps what is not so inevitable is the son's death in the infirmary on the prison ship rather than joining such notable London thieves and pickpockets as Jack Dawkins ("The Artful Dodger") from Oliver Twist down under at Botany Bay. Cruikshank precludes the possibility of any sort of happy ending for the wayward son. In a later Dickens novel, the street-thug Abel Magwitch makes the same journey but redeems himself by labouring on behalf of the blacksmith's boy who assisted him after his escape. Cruikshank, in contrast, consigns his boy-thief to the oblivion of the Atlantic.

After Cruikshank "took the pledge" to abstain from imbibing spiritous liquors in 1848, the calibre of his work began a long, slow decline. Despite his mistaken notion that drink causes social problems rather than that alcoholism is one of the consequences of poverty, his second sequence derives considerable narrative power from the double tragedy of two young lives wasted in the Great Sink of London. With its perfect realisations of the low life of the metropolis — the gin-palace, beer-shop, betting-parlour, dance-hall, and three-penny lodging-house, The Drunkard's Children proved as popular as The Bottle with the lower-middle and working classes. David Kunzle in "Cruikshank's Strike for Independence" has labelled the 1848 folio "perhaps the artist's last truly creative performance, and his only truly successful attempt to combine the covered dual role of artist-as-author" (p. 169). But, engaging as the eight images are, Cruikshank leaves narrative gaps between them that even his longer captions fail to fill. How, for example, does the daughter become a prostitute and for what crimes is the son sentenced at the Old Bailey to transportation? The result is a hyper-realistic comic strip with holes that the viewers must fill for themselves. Otherwise, however, The Drunkard's Children should be regarded as a sequel to The Bottle in that it follows the curse of alcoholism from the older to the younger generation, wiping out both parents and children.

Analysis of the illustration

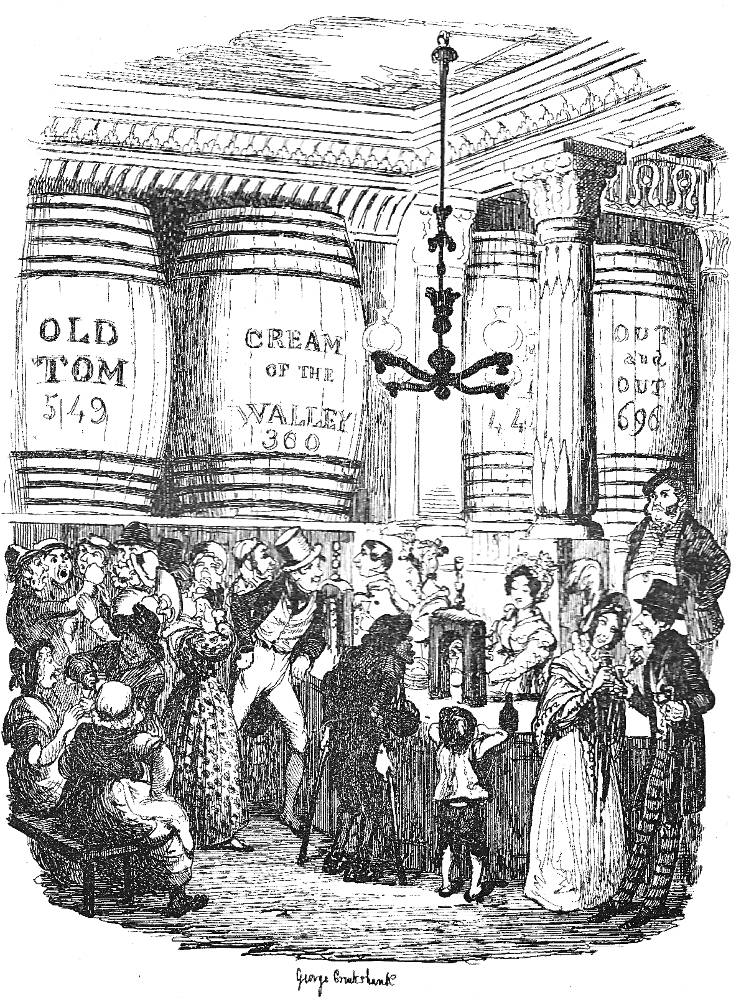

The gin shop depicted here has customers that are not quite on a par socially with those of the establishment that Cruikshank drew for Dickens's Sketches by Boz in 1836, — and the lame and even children are imbibing greedily. However, whereas the huge barrels of gin with fanciful titles dominate the establishment in the 1836 illustration, here Cruikshank's focus is the mixed-gender crowd of drinkers. Thirteen of the figures (including the cigarette-smoking manager, left) are males, fifteen females — so that one might conclude that alcoholism, the bane of the working classes, afflicted members of both sexes about equally. At the very centre, with a serious and thoughtful expression is the drunkard's daughter, small glass in hand. The brother, smoking a long-stemmed pipe, is in front of the door to the right; apparently an older man is trying to persuade him to drink from a substantial tankard. (In the interim between his work on the previous series and this, in addition to taking the Temperance pledge, George Cruikshank, a life-long smoker, had renounced the smoking of tobacco as a noxious, filthy habit.) The long-haired youth immediately beside the daughter here appears again in the dance-hall (Plate 3), although there she is dancing a polka with another well-dressed artisan. In the dancing scene, Cruikshank individualises the animated dancers by the variety of their movements and poses, but only such details as the huge shawl (right of centre) readily enable him to distinguish individuals who are neither grotesques nor children.

Commentary by Richard A. Vogler (1979)

In his "Notes on the Illustrations," Vogler describes the particulars of each scene, focussing on the recurring figures of the Drunkard's son and the Drunkard's daughter, who are almost lost in the crowded rooms of the first three illustrations, in contrast to their isolation in the cold cell of their maniac father in the last scene of The Bottle. Curiously, he does not describe the setting of this first, densely-packed barroom scene as a "gin-palace," although its detailing suggests that it is somewhat like Cruikshank's illustration of such a place in Sketches by Boz (1836), with its gigantic barrels of gin dwarfing the imbibers.

By this time Cruikshank had become a convert to the temperance movement and thus had anassured audience for this work regardless of whether it attained the success of its predecessor.. . . . Once again the work is most effective in the expensive hand-colored issues. There seems to be no appreciable difference in the artist's attitude towards his subject in the two suites. The sequel, neither more nor less doctrinaire than the original work, is more dramatic and createsmore historical interest than the original because its designs portray a variety of settings and are replete with character types. The drunkard's son appears in six of the designs; the daughter, in only five. Since the captions for The Drunkard's Children are longer and of more importance than those for the first series, the second suite becomes more of a narrative. . . . . This suite gives scenes of lower-class Victorian life that were seldom portrayed in the arts of the period. [p. 161].

[Cruikshank sets the scene in a] typical low-class tavern. The daughter stands in the middle of the crowd. The son, who has now taken up smoking, stands on the right, facing two older, hardened, and, perhaps, criminal types, one of whom offers the youngster a mug of ale. A wretched family huddles in the right foreground, the mother pouring gin into the mouth of her daughter, as was commonly done to pacify children and ward off their hunger pangs. Behind the counter a rotund, evil-looking publican drops money into his coin purse. As is usual with Cruikshank, all of the names of the liquor in the shop are intended to show the irony of the wretched-looking group disporting themselves before encomiums such as "Cream of the Valley," "The Celebrated Double Gin," and "Families Supplied with Wines and Spirits" [as in Cruikshank's liquor emporium in the first series, Unable to Obtain Employment, They Are Driven by Poverty into the Streets to Beg, and by This Means They Still Supply the Bottle]. On the left a drunken gin lover spills his drink and drops the money probably intended to entice the tipsy woman picking it up, while a snaggletoothed cripple already in his cups looks on with envy. The young daughter, holding a glass of gin but looking strangely aloof, is being counseled by an older woman, her face hidden by a large bonnet, and ogled by a young man on her right. The meaning of this scene becomes clear after scrutiny of Plate III. With this series the prints become more meaningful when studied in sequence and when carefully compared with one another. [p. 163]

Blanchard Jerrold on Cruikshank's similar illustrations of Dickens

In his illustrations to Sketches by Boz, Cruikshank first approached intemperance from that point of view in which he treated it afterwards in The Bottle. His view of the gin-shop [above, left] comprehends a complete story.

"We have sketched this subject," says Dickens, "very slightly, not only because our limits compel us to do so, but because, if it were pursued further, it would be painful and repulsive. Well-disposed gentlemen and charitable ladies would alike turn with coldness and disgust from a description of the drunken besotted men and wretched, broken-down, miserable women, who form no inconsiderable portion of the frequenters of these haunts; forgetting, in the pleasant consciousness of their own high rectitude, the poverty of the one and the temptation of the other. Gin-drinking is a great vice in England, but poverty is a greater; and until you can cure it, or persuade a half-famished wretch not to seek relief in the temporary oblivion of his own misery with the pittance which, divided among his family, would just furnish a morsel of bread for each, gin-shops will increase in number and splendour. If Temperance Societies could suggest an antidote against hunger and distress, or establish dispensaries for the gratuitous distribution of bottles of Lethe-water, gin palaces would be numbered among the things that were. Until then, their decrease may be despaired of." Dickens here glanced, and only carelessly, at the surface of the great question. This poverty which he deplored was the result of the drink. The Lethe-water would be unnecessary if the gin-and-water were stopped. Poverty, dirt, hunger, promote the publican’s trade; but this trade breeds the misery on which it thrives. The quartern which the father drinks, helps to raise a customer in his son, for the trade of the publican's son. More than ten years elapsed before this view of the Temperance question was destined to have complete sway and mastery over the genius of Dickens's illustrator; but already he saw deeper into it, because he looked more earnestly into it than the writer, who had not yet done with the comedy element of drunkenness. [cited by Jerroldin "Epoch II: 1848-1878: Chapter 1, 'At Gillray's Grave,'" p. 84]

Visual Continuity in the Second Sequence

Whereas in illustrating Dickens Cruikshank had to attend to the details in the text and shape his conception of the drinking scene accordingly, much to his delight in his project for the Temperance Union he could control the storyline in his own "wordless" novella, The Drunkard's Children. In his continuation of this sordid tale of two generations destroyed by gin, Cruikshank had to rely only on repeating characters, whereas, in The Bottle, he was able to repeat a single room to demonstrate the family's decline. Moreover, in the 1848 sequence a number of the scenes are so highly crowded that the viewer sometimes has to search for the continuing figures of the Drunkard's son and daughter, upon whom the illustrator is relying to provide visual continuity.In this sequel, Cruikshank employs a number of settings associated with proletarian London: a gin-palace here, a beer-shop, the dancing-rooms, a three-penny lodging house, the courtroom of the Old Bailey, a lockup, an infirmary aboard a prison transport, and one of the newer bridges across the Thames in The Maniac Father and the Convict Brother are gone — the Poor Girl, Homeless, Friendless and Deserted, Destitute, and Gin-mad Commits Self Murder.

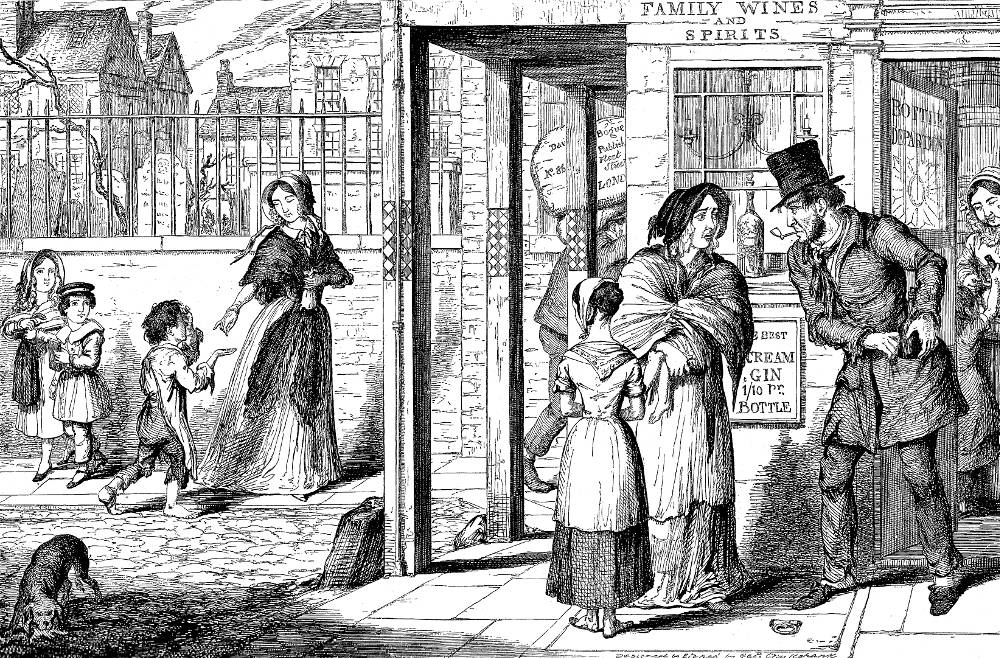

Cruikshank's illustrations of other drink shops, bars, and taverns, 1836-37

Left: The original Cruikshank engraving of an 1830s "Gin Palace," The Gin Shop (1836). Centre: Cruikshank's cancelled plate from Sketches by Boz of a social club whose principal activities are smoking and drinking, The Free and Easy (8 February 1836). Right: Cruikshank's illustration of one of the boozey haunts of housebreaker Bill Sikes, a beer shop, in Oliver claimed by his affectionate friends (September 1837). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Cruikshank's external description of the drink-shop, juxtaposed against a cemetery, in The Bottle: Unable to Obtain Employment, They Are Driven by Poverty into the Streets to Beg, and by This Means They Still Supply the Bottle. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Related Material

- George Cruikshank and Charles Dickens

- The Gin-Shop

- "Great is thy power, O Gin" — Reynold's sermon on the harm it does to the poor

- London Gin Shops

- Victorian Dancing: The Waltz and the Polka

- "Frauds on the Fairies" (1 October 1853)

- Temperance, Teetotalism, and Addiction in the Nineteenth Century

- Addiction in the Nineteenth Century

- Drunkedness and the ease of obtaining alcohol

- Alcohol and Alcoholism in Victorian England

- The Band of Hope Review

Bibliography

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Cruikshank, George. The Drunkard's Children. A Sequel to "The Bottle." London: David Bogue, 1848.

James, Louis. "An Artist in Time: George Cruikshank in Three Eras." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 156-187.

Jerrold, Blanchard. The Life of George Cruikshank. In Two Epochs. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. 2 vols. London: Chatto and Windus, 1882.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

Kunzle, David. "Mr. Lambkin: Cruikshank's Strike for Independence." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 169-88.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Meisel, Martin. Chapter 7, "From Hogarth to Cruikshank." Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1989. Pp. 97-141.

Mellby, Julie L. "More than 100,000 copies sold in the first few days." Graphic Arts: Exhibitions, acquisitions, and other highlights from the Graphic Arts Collection, Princeton University Library. Web. 13 April 2011. https://blogs.princeton.edu/graphicarts/2011/04/the_bottle.html

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Last modified 17 August 2017