Tom Puss, catching a Rabbit..in the Rabbit Warren (7 cm high by 9.8 cm wide, framed, facing page 8) — the second illustration for both the single-volume edition of 1864 and for the fourth and final tale in the 1865 anthology, George Cruikshank's Fairy Library. Dressed in a suit of clothes worthy of a courtier, Tom Puss makes his way from the mill belonging to the three sons and the father, the miller, passing though a dense, enchanted wood. Discovering in its midst a massive rabbit warren, Puss traps two enormous rabbits as presents for the king. Cruiikshank explains that, as a consequence of a spell cast by an ogre, for some time in the kingdom there has been a shortage of rabbits, the favourite meat of the ruler. Consequently, a present to the king of a brace of rabbits from the Marquis of Carabas (in other words, Tom's master, Caraba) will pave the way for Tom's creating a positive relationship between Caraba and the royal family.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

The illustrations appearing here are from the collection of the commentator.

Cruikshank, George. Puss in Boots. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London & Edinburgh: Routledge, Warne, and Routledge. 40 pages; with six etching plates on steel by George Cruikshank (1792-1878) famed English caricaturist, illustrator with 'fine artistic power' [Chambers]; here, with suitably humorous and sarcastic Cruikshank caricatures throughout in black and white in the classic children's fable of the jaunty Cat, the plate pages often with more than one image; this being one of the "George Cruikshank's Fairy Library" books; original illustrated light blue paper wraps.

Passage Illustrated

"Now, let's to work. In the first place, Master, I must have a dress with a cap and feather, and though last, not least, a pair of Boots!"

"Where am I to get these things?" said Caraba. "Go look in the little oak box in the lumber cupboard under the mill, where I sleep and you will find all I want." Caraba did as he was told, and sure enough there were the clothes and a little pair of boots that fitted Puss like a pair of gloves.

The cat, with the assistance of his master, was soon dressed. "And now," said Puss, " hand me that little bag that hangs up there behind the door, and give me that little bit of a stick that you tickle the donkey's ribs with when you want him to go faster, and I am off;" and going to the door, said, "Good-bye, master, say nothing to nobody about this, but keep your spirits up till I come back."

Caraba was lost in wonder, as he saw Puss walking along just like a little man, and wondered what he could be going to do with the bag; but he could not form a guess. So, having watched Master Tom Puss out of sight, and having duties to attend to, he went to his work.

Between the mill and the Kinir's castle there was a wood, and one part of it was so thick with trees and bushes that no one could pass through it; and although the woodmen had often tried to clear this part, it appears they found that what they cut down in the day-time, always grew up again in the night, and so they gave it up; but Tom found his way through this thicket, and not only that, but also found some rabbits inside. Yes, there was a large rabbit-warren in the centre, with thousands of "bunnies" playing about in all directions. Puss crept in very gently, placed the bag on the ground, propped the mouth of it open with a bit of stick, to which was tied a string, and having put some nice cabbage-leaves at the end, thus made a sort of trap of it ; then lying down upon the ground with the end of the string in his paw, watched to see if any of the rabbits would be tempted to go into the bag after the cabbage-leaves, which one soon did. Tom pulled the string: down came the stick, and Puss had thus, as the sportsmen say, "bagged" a fine rabbit ! And having trapped another one, Puss came out of the warren, not to take the rabbits to his master ; no, Tom Puss not only knew his way through the thicket, and that there was a rabbit-warren inside of it, but he also knew that the king was extremely fond of that sort of food, and although always wanting it, could never get any, for not one of those little creatures had been seen in his kingdom for many years. It was found out afterwards that a wicked Ogre, who was a sorcerer, had shut in all the rabbits in this warren, out of spite to the King, because he was a very good man, and because no one should have any rabbits but himself. — "Puss in Boots," pp. 7-9.

The Context in Perrault

"Do not be so concerned, my good master. If you will but give me a bag, and have a pair of boots made for me, that I may scamper through the dirt and the brambles, then you shall see that you are not so poorly off with me as you imagine."

The cat's master did not build very much upon what he said. However, he had often seen him play a great many cunning tricks to catch rats and mice, such as hanging by his heels, or hiding himself in the meal, and pretending to be dead; so he did take some hope that he might give him some help in his miserable condition.

After receiving what he had asked for, the cat gallantly pulled on the boots and slung the bag about his neck. Holding its drawstrings in his forepaws, he went to a place where there was a great abundance of rabbits. He put some bran and greens into his bag, then stretched himself out as if he were dead. He thus waited for some young rabbits, not yet acquainted with the deceits of the world, to come and look into his bag.

He had scarcely lain down before he had what he wanted. A rash and foolish young rabbit jumped into his bag, and the master cat, immediately closed the strings, then took and killed him without pity. — Charles Perrault, "The Master Cat or, Puss in Boots."

Commentary

After the former illustration, Tom Puss, consoling his Master, and asking for a Pair of Boots & a suit of Clothes, the reader is prepared for Tom Puss to show himself a shrewd strategist. However, the creature's discovery of the densely populated rabbit-warren in the midst of an impenetrable thicket does strike one as something of a coincidence. Nevertheless, Cruikshank presents the episode with sufficient detail in both the text and the illustration to render it plausible. The dense oak forest in the backdrop contrasts effectively with the sunlit rabbit-warren, and Cruikshank individualizes the rabbits by their postures and features. But the chief figure is Tom Puss, pretending to be asleep as he waits for the unsuspecting rabbit, right of centre, to enter the trap. Cruikshank even injects an element of suspense as the reader wonders whether the large white rabbit, standing on his hind legs (and therefore, perhaps, possessed of something of Tom Puss's human intelligence), will alert his comrade in the nick of time and prevent his going into the bag.

Bravely Cruikshank issued his Cinderella later in 1854, though Dickens had parodied it, as if in advance, in "Frauds on the Fairies". . . . Not only did the artist refuse to compromise his editing principles, but appended a note "To the Public" in which readers who might fall into same heresies as "my friend Charles Dickens" were advised to read his "Letter" to that gentleman. But, for whatever reason, interest in Cruikshank's fairy tales seems to have diminished; for his next contribution, Puss in Boots, though probably completed in 1853 or 1854, was not published until 1864. The artist probably held Dickens responsible for the hiatus; certainly he was still smarting from the artist's reprimand. — Jane Rabb Cohen, p. 35.

Indeed, the composition of the duel-scene illustration has much in common with the series for for Cinderella and The Glass Slipper as the illustrator repeats the figures of Cinderella and Tom Puss to maintain pictorial-narrative continuity, and thereby reveal the protagonist's relationships with all the other characters in the story. Whereas in Hop-0' My-Thumb and the Seven-League Boots Cruikshank had split his pages in three, producing tiny plates with difficult-to-read captions, in the last two in the 1865 anthology he divides three pages into two illustrations and just one (The Orgre's transformations into three, so that the narrative-pictorial sequence is quite clear. George Cruikshank, not showing himself much of a hand at landscape in illustrating Dickens's Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People and Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress (consider the ineffective use of perspective and the natural setting, for example, in Sikes attempting to destroy his dog, Part 21, January 1839), provides scenicl backdrops every bit as credible and engaging as those by seascape artist Clarkson Stanfield in Dickens's The Haunted Man; or, The Ghost's Bargain (December 1848) — for example, The Lighthouse. In fact, in the six full pages of illustration for Puss in Boots (probably composed in 1854 or 1855, but not published until ten years later), seven of the eleven panels are exterior scenes showing the varied countryside beyond the mill and the market-town, and thereby increasing the credibility of a story in which the cat turns out to be a depressed game-keeper and the miller the rightful Marquis of Carabas, usurped by an ogre (not unlike the situation involving the Danish Giant and Sir Ethelbert in Cruikshank's Jack and the Bean-stalk).

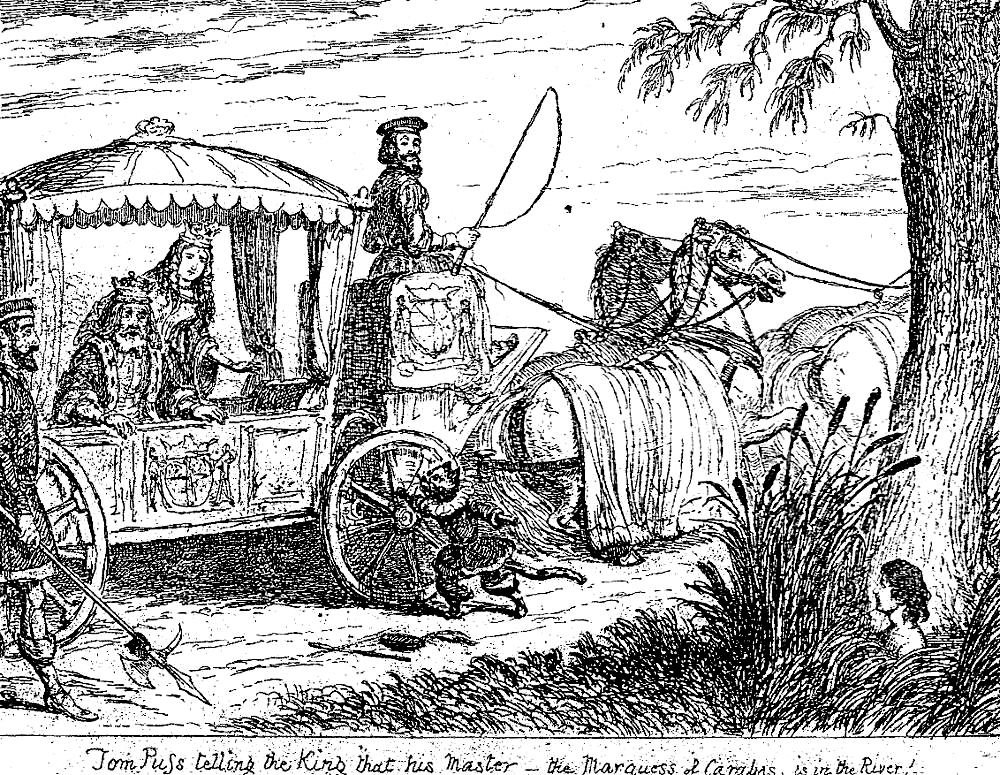

The other scenes containing the convincing landscapes

Left: Cruikdshank's theatrical cutaway of the granary showing the high country beyond the mill, Tom Puss, consoling his Master, and asking for a Pair of Boots & a suit of Clothes (facing p. 3). Centre: Cruikshank's roadside scene in which Tom Puss waylays the King's carriage, Tom Puss telling the King that his Master .. the Marquiss of Carabas, is in the River (facing p. 12). Right: George Cruikshank's beautifully detailed, Tennysonian description of the peasantry in the fields, Tom Puss commands the Reapers to tell the King that All the fields belong to the Most Noble, the Marquess of Carabas (1854). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Related Materials

- "Frauds on the Fairies" (1 October 1853)

- Editor's Note on "Frauds on the Fairies"

- Defending the Imagination: Charles Dickens, Children's Literature, and the Fairy Tale Wars

- George Cruikshank and Charles Dickens

- Fairy Tales: Surviving the Evangelical Attack

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas; Michael Slater and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

British Library. "George Cruikshank's Fairy Library." Romantics and Victorians. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/george-cruikshanks-fairy-library

Carpenter, Humphrey, and Mari Pritchard. The Oxford Companion to Children's Literature. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1984.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Cruikshank, George. Puss in Boots. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. The fourth volume in George Cruikshank's Fairy Library. London: Routledge, Warne & Routledge, 1864. (Price one shilling) 11 etchings on 6 tipped-in pages, including frontispiece.

Cruikshank, George. George Cruikshank's Fairy Library: "Hop-O'-My-Thumb," "Jack and the Bean-Stalk," "Cinderella," "Puss in Boots". London: George Bell, 1865.

Daniels, Morna. "The Tale of Charles Perrault and Puss in Boots." Electronic British Library Journal. 2002. pp. 1-14. http://docplayer.net/21672800-The-tale-of-charles-perrault-and-puss-in-boots.html

Guildhall Library blog. "A Gem from Guildhall Library's Shelves: George Cruikshank's Fairy Library by George Cruikshank published by Routledge in London (c. 1870)." 8 August 2014. https://guildhalllibrarynewsletter.wordpress.com/2016/08/08/a-gem-from-guildhall-librarys-shelves-george-cruikshanks-fairy-library-by-george-cruikshank-published-by-routledge-in-london-c1870/

Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University. "George Cruikshank." http://library.tulane.edu/exhibits/exhibits/show/fairy_tales/george_cruikshank

Hubert, Judd D. "George Cruikshank's Graphic and Textual Reactions to Mother Goose." Marvels & Tales, Volume 25, Number 2, 2011 (pp. 286-297). Project Muse. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/462736/pdf

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

Kotzin, Michael C. Dickens and the Fairy Tale. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1972.

Perrault, Charles. "The Master Cat or, Puss in Boots." Folklore and Mythology Electronic Texts, University of Pittsburgh, 2002. From Andrew Lang's The Blue Fairy Book (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., ca. 1889), pp. 141-147. Edited by D. L. Ashliman. http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/perrault04.html

Schlicke, Paul. "

Stone, Harry. Dickens and the Invisible World: Fairy Tales, Fantasy, and Novel-Making. Bloomington, IN: Indiana U. P., 1979.

Vogler, Richard, The Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. New York: Dover, 1979.

Last modified 5 July 2017