He felt the chilling influence of its death-cold eyes

A. A. Dixon

1906

Lithographic reproduction of watercolour

12.2 cm high x 8.1 cm wide

Frontispiece for The Christmas Books, Collins' Pocket Edition (1906), facing title-page.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

One of the most frequently illustrated moments in the Dickens canon is the scene in which miser and misanthrope Ebenezer Scrooge encounters the ghost of his former business partner, Jacob Marley, now seven-years-dead. [Commentary continued below.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated from Stave One, "Marley's Ghost"

His colour changed though, when, without a pause, it came on through the heavy door, and passed into the room before his eyes. Upon its coming in, the dying flame leaped up, as though it cried, "I know him! Marley's Ghost!" and fell again.

The same face: the very same. Marley in his pigtail, usual waistcoat, tights, and boots; the tassels on the latter bristling, like his pigtail, and his coat-skirts, and the hair upon his head. The chain he drew was clasped about his middle. It was long, and wound about him like a tail; and it was made (for Scrooge observed it closely) of cash-boxes, keys, padlocks, ledgers, deeds, and heavy purses wrought in steel. His body was transparent; so that Scrooge, observing him, and looking through his waistcoat, could see the two buttons on his coat behind.

Scrooge had often heard it said that Marley had no bowels, but he had never believed it until now.

No, nor did he believe it even now. Though he looked the phantom through and through, and saw it standing before him; though he felt the chilling influence of its death-cold eyes; and marked the very texture of the folded kerchief bound about its head and chin, which wrapper he had not observed before; he was still incredulous, and fought against his senses. [Stave One, "Marley's Ghost," p. 22]

Commentary

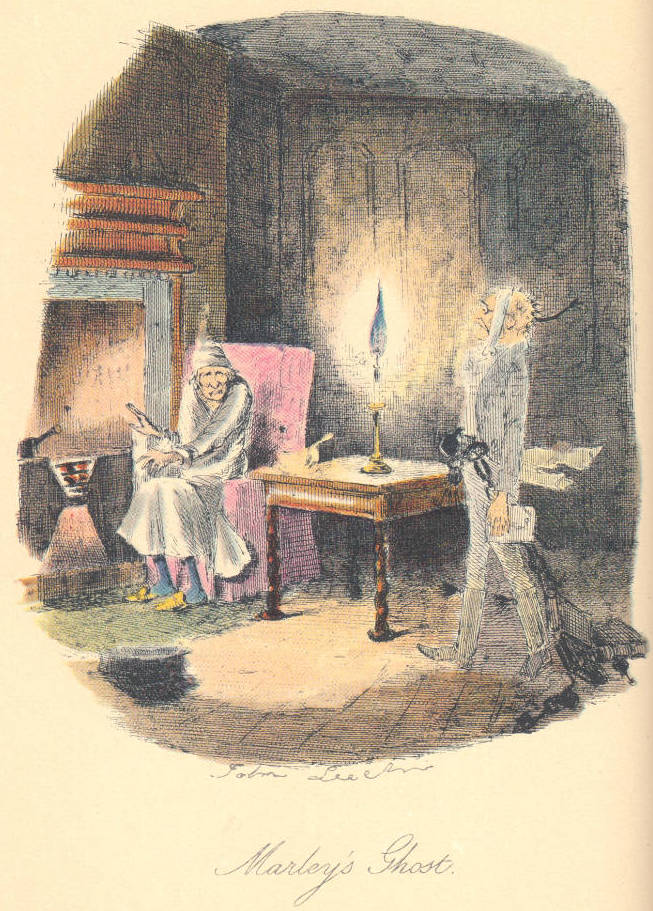

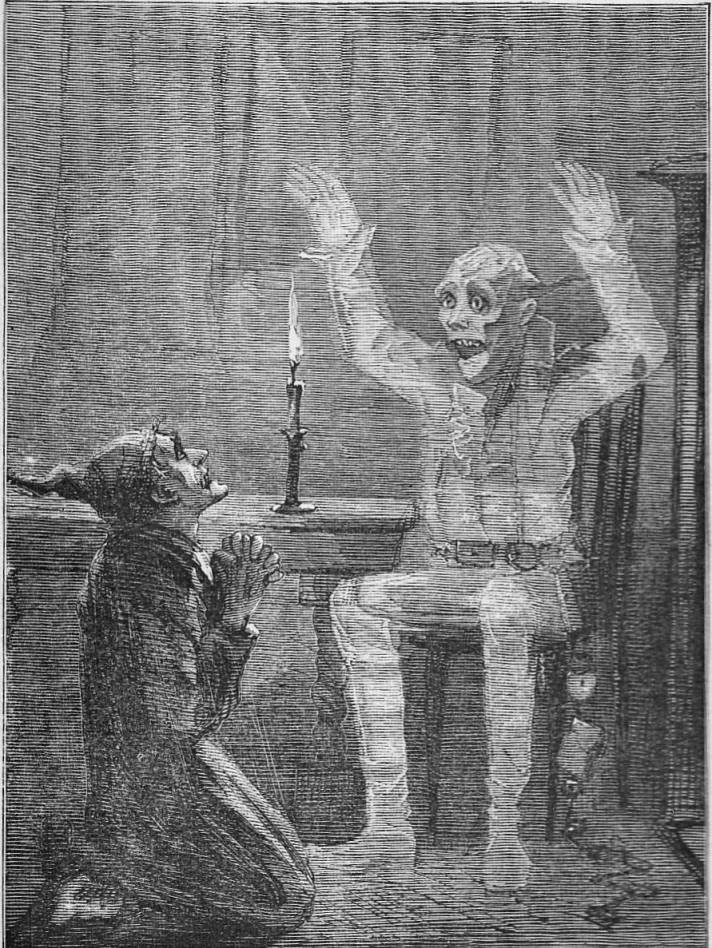

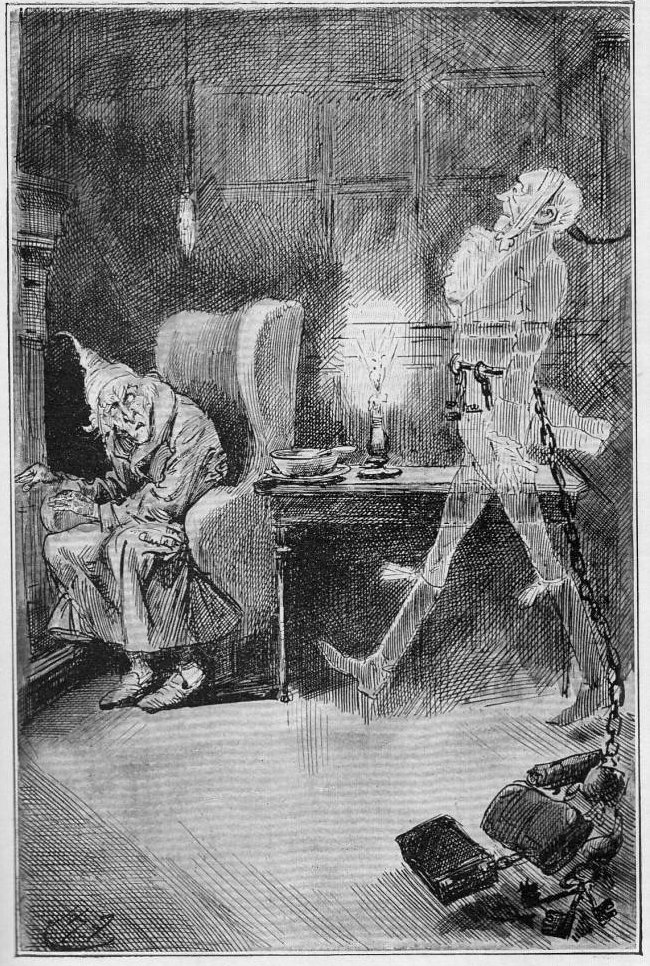

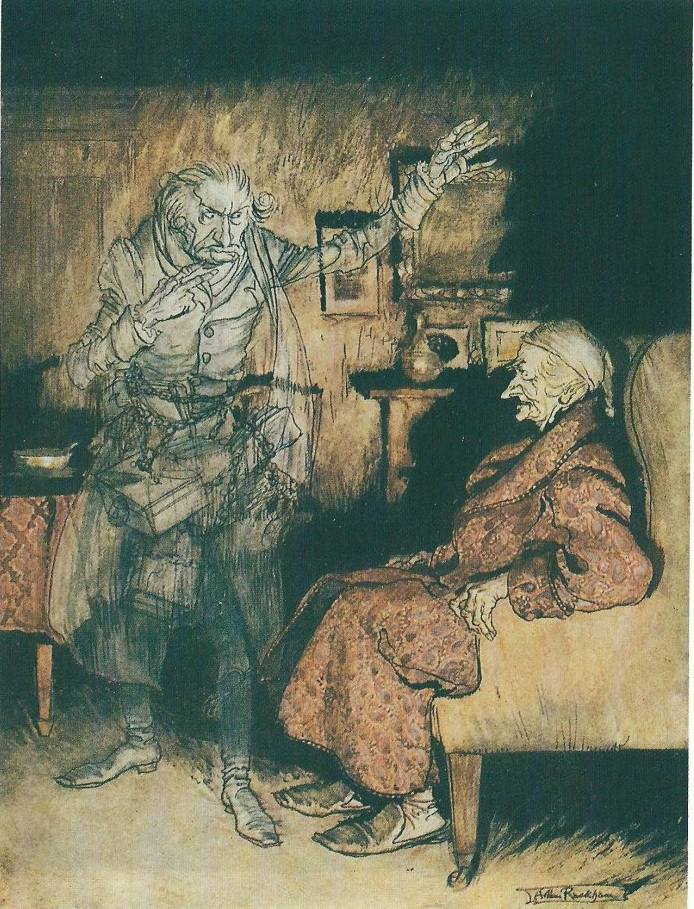

Every major illustrator of A Christmas Carol, including John Leech, has attempted to realise this dramatic metaphysical visitation. Punch cartoonist John Leech in the original scarlet volume published in December 1843 set the terms of illustration for eight of the scenes in the novella, including the arrival of Marley's ghost from the depths of Scrooge's subconscious and the borders of the unseen world, a pictorial rendition to which all subsequent illustrators have in some way responded. Sol Eytinge, Junior, in his wood-engravings for 1867 Diamond Edition of The Christmas Books (the first such anthology of the five novellas written between 1843 and 1848 as "seasonal offerings") and in the twenty-fifth anniversary A Christmas Carol the following year reacted to Leech's composition by moving in for a closeup, first with a repentant and terrified Scrooge on his knees in Scrooge and The Ghost and subsequently with Marley's Ghost, in which the American illustrator's focus is clearly Scrooge's remorse in the former and terror in the latter, the Ghost being transparent and seated in both, but rather more effectively imagined in the 1868 single-volume edition of the novella. In contrast, the other post-Leech illustrators realise the moment when the Ghost enters the room, when Scrooge is still trying to eat his gruel in front of a cold fire (not even shown in the Dixon illustration). As opposed to Eytinge's minimalist treatments and E. A. Abbey's numinous atmosphere and modelled treatment of the mortal and the spirit in the darkened room, Barnard's rather more cartoon-like treatment is highly dynamic as the bed-curtains and bell-pull writhe in the presence of the tortured spirit. Viewed against this pictorial tradition, Dixon's interpretation seems rather pallid, and lacking in the tongue-in-cheek humour of Leech's original conception, which influenced the next major illustrator, Harry Furniss in Marley's Ghost (1910).

With the advantage of being able to review so many earlier interpretations of this telling (one might even say "transformative") moment, Dixon might have achieved an interesting synthesis of the gothic, the humorous, and the naturalistic. Instead, however, he focuses on making the characters look real, that is, three dimensional and natural in their postures and expressions, and thereby fails to realize the chief elements of the text: Scrooge's fear (which he covers up with humorous bravado and clever witticisms) and the gothic atmosphere of the encounter. No agonized former capitalist labours under chains forged in life, and no terror strikes the recipient of the visit here. A. A. Dixon does, however, make these former business partners similar types physically, although the proportions are off: in order to accommodate a seated Scrooge and a standing Marley, Dixon has, in fact, made the ghost much shorter. More to the point, the lithograph based on a water-colour shows a Scrooge too young and not sufficiently affected by the uncanny visitor, who does not seem particularly animated or terrifying. The salient details of Scrooge's sitting room are generally absent, although Dixon has given the bowl of gruel and the candle a central position in the composition. Odd details include Scrooge's fur-collared dressing-gown; rich waitcoast; comfortable, florally embroidered slippers; and the flagstone floor — which occupies rather too much of the picture. Had Dixon been able to study the frontispiece to the American Household Edition (which, owing to restrictive copyright laws on both sides of the Atlantic he likely could not), he might have chosen a vertical orientation and thereby given himself greater scope for depicting the figures more plausibly in their proper proportions in a sufficiently detailed setting. More to the point, he might have sought to capture the eerie atmosphere that Abbey so effectively creates through the use of shadow in that 1876 wood-engraving.

Related Illustrations from Other Editions, 1843-1915

Upper Left: John's Leech's "Marley's Ghost" (1843); upper centre: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s "Scrooge and The Ghost" (1867); upper right: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s "Marley's Ghost" (1868); lower centre: E. A. Abbey's "Marley's Ghost" (1876). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Left: Fred Barnard's "Marley's Ghost" (1878); centre: Harry Furniss's "Marley's Ghost" (1910); right: Arthur Rackham's "'How now' said Scrooge, caustic and cold as ever 'What do you want with me?'" (1915). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

References

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Canton, Ohio: Ohio U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge. New Haven: Yale U. P., 1990.

Dickens, Charles. The Christmas Books. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

Dickens, Charles. The Christmas Books. Il. Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 8.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Il. John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1868.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Il. Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. 1.

Hearn, Michael Patrick, ed. The Annotated Christmas Carol. New York: Avenel, 1976.

Victorian

Web

Illus-

tration

A. A.

Dixon

Great

Expectations

Next

Last modified 26 March 2014