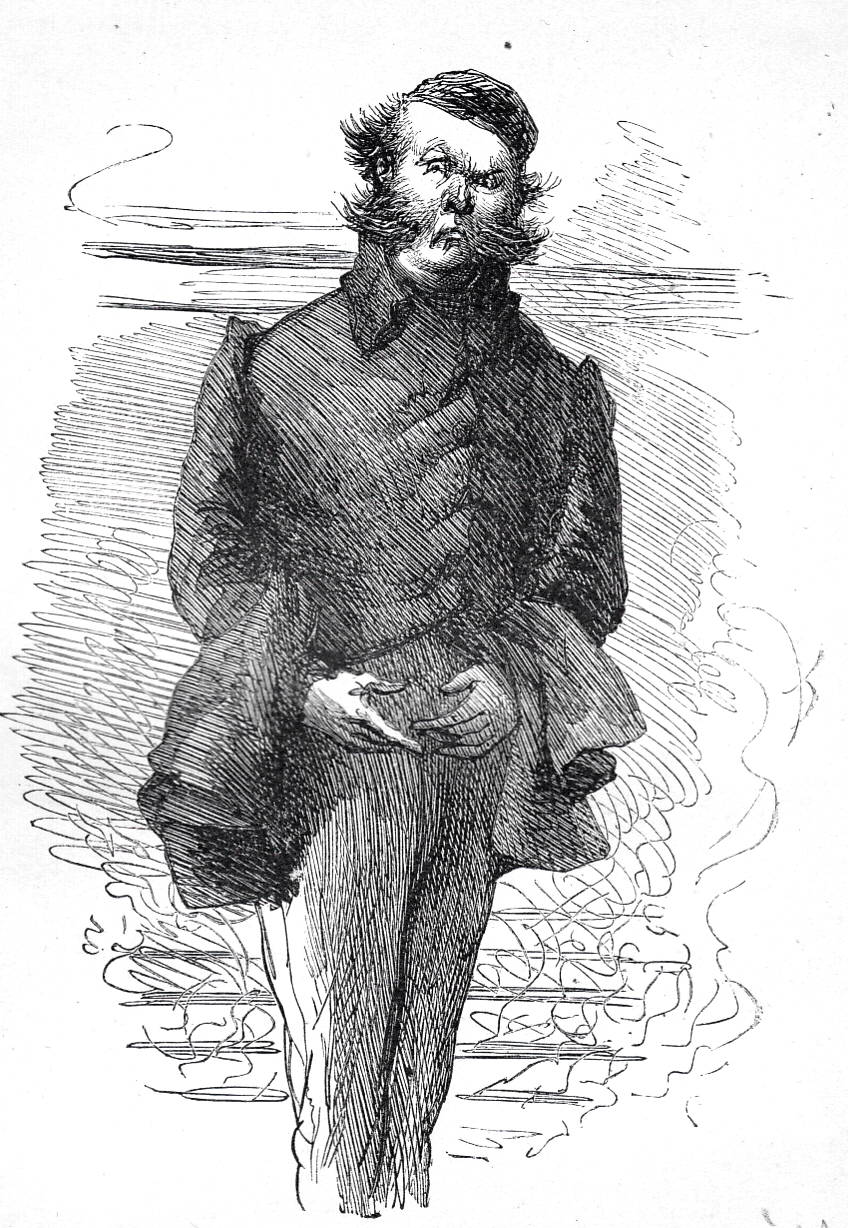

Captain Dowler

Sol Eytinge

Wood engraving, approximately 10 cm high by 7.5 cm wide (framed)

Illustration for Dickens's The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club in the Ticknor and Fields (Boston, 1867) Diamond Edition, facing p. 291.

In this eleventh full-page character study for the last novel in the compact American publication, Eytinge focus on a single character whom the Pickwickians encounter on their journeys. "A stern-eyed man of about five and forty, who had a bald and glossy forehead, a good deal of black hair at the sides and back of his head and large black whiskers" (291). [continued below]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Mr. Dowler is but one in a long line of choleric types who go all the way back to Homer's Polyphemus, and who are well represented in Dickens's early works with such figures as Captain Waters in "The Tuggses at Ramsgate" (31 March 1836), the Pugnacious Cabman (April 1836), and Dr. Slammer earlier in The Pickwick Papers. We meet the type countless times in the Dickens canon, but he is perhaps best represented by the irascible Major Joseph Bagstock in Dombey and Son — also retired from the military and inclined to treat social inferiors with contempt — and the thoroughly unpleasant, black-whiskered Edward Murdstone in David Copperfield.

An interesting wrinkle in the cloth from which Boz cuts him is that, like the Reverend Stiggins, Dowler is essentially a hypocrite in that he rants like a modern Miles Gloriosus, particularly (like Captain Waters in "The Tuggses") in defence of his wife's honour, but runs like Sir John Falstaff when he believes he is in danger. Ironically, in running away to Bristol to avoid confronting Winkle, whom he challenges to a duel, Dowler goes precisely where Winkle has fled. Dickens initially describes Dowler as "strange," then as "fierce," but does not specify anything about him except that his whiskers are "military," so that Eytinge has taken a liberty in interpreting Dowler's costume as that of an officer in the British army of the period. Dowler is the first new character whom Dickens introduces after the trial scene, and his introduction here is perfectly consistent with the novel's picaresque character and episodic structure. The passage realised in this image comes from chapter 35.

The Pickwickians first encounter the gruff-voiced, fierce-visaged Dowler, a former military officer who has gone in for a commercial career, in the travellers' room at The White Horse or White House Cellar, a London coaching office at Arington Street and Piccadilly, where The Ritz Hotel presently stands. This was the starting point for coaches bound for the west of England, including Bath and Bristol. They will have further adventures in Bath's Royal Crescent with the Dowlers when the retired Captain mistakenly believes that Winkle is about to run off with his wife.

"I wonder whereabouts in Bath this coach puts up," said Mr. Pickwick, mildly addressing Mr. Winkle.

"Hum — eh — what's that?" said the strange man.

"I made an observation to my friend, sir," replied Mr. Pickwick, always ready to enter into conversation. "I wondered at what house the Bath coach put up. Perhaps you can inform me."

"Are you going to Bath?" said the strange man.

"I am, sir," replied Mr. Pickwick.

"And those other gentlemen?"

"'They are going also," said Mr. Pickwick.

"Not inside — I'll be damned if you're going inside," said the strange man.

"Not all of us," said Mr. Pickwick.

"No, not all of you," said the strange man emphatically. 'I've taken two places. If they try to squeeze six people into an infernal box that only holds four, I'll take a post-chaise and bring an action. I've paid my fare. It won't do; I told the clerk when I took my places that it wouldn't do. I know these things have been done. I know they are done every day; but I never was done, and I never will be. Those who know me best, best know it; crush me!" Here the fierce gentleman rang the bell with great violence, and told the waiter he'd better bring the toast in five seconds, or he'd know the reason why.

"My good sir," said Mr. Pickwick, "you will allow me to observe that this is a very unnecessary display of excitement. I have only taken places inside for two."

"I am glad to hear it," said the fierce man. "I ithdraw my expressions. I tender an apology. There's my card. Give me your acquaintance."

'With great pleasure, Sir,' replied Mr. Pickwick. "We are to be fellow-travellers, and I hope we shall find each other's society mutually agreeable.""I hope we shall," said the fierce gentleman. "I know we shall. I like your looks; they please me. Gentlemen, your hands and names. Know me."

Of course, an interchange of friendly salutations followed this gracious speech; and the fierce gentleman immediately proceeded to inform the friends, in the same short, abrupt, jerking sentences, that his name was Dowler; that he was going to Bath on pleasure; that he was formerly in the army; that he had now set up in business as a gentleman; that he lived upon the profits; and that the individual for whom the second place was taken, was a personage no less illustrious than Mrs. Dowler, his lady wife.

"She's a fine woman," said Mr. Dowler. "I am proud of her. I have reason."

"I hope I shall have the pleasure of judging," said Mr. Pickwick, with a smile.

"You shall," replied Dowler. "She shall know you. She shall esteem you. I courted her under singular circumstances. I won her through a rash vow. Thus. I saw her; I loved her; I proposed; she refused me. — "You love another?" — "Spare my blushes." — "I know him." — "You do." — "Very good; if he remains here, I'll skin him."'

"Lord bless me!" exclaimed Mr. Pickwick involuntarily.

"Did you skin the gentleman, Sir?" inquired Mr. Winkle, with a very pale face.

"I wrote him a note, I said it was a painful thing. And so it was."

"Certainly," interposed Mr. Winkle.

"I said I had pledged my word as a gentleman to skin him. My character was at stake. I had no alternative. As an officer in His Majesty's service, I was bound to skin him. I regretted the necessity, but it must be done. He was open to conviction. He saw that the rules of the service were imperative. He fled. I married her. Here's the coach. That's her head." [Chapter 35, p. 291-292]

Other artists who illustrated this work

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Adventures of the Pickwick Club. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1869.

Dickens, Charles. "Pickwick Papers (1836-37). Il. Hablot Knight Browne. The Charles Dickens Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. "Pickwick Papers (1836-37). Il. Hablot Knight Browne. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873.

Dickens, Charles. "Pickwick Papers (1836-37). Il. Thomas Nast. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Bros., 1873.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens. Vol. 1. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978.

Victorian

Web

Illus-

tration

Pickwick

Papers

Sol

Eytinge

Next

Last modified 22 February 2012