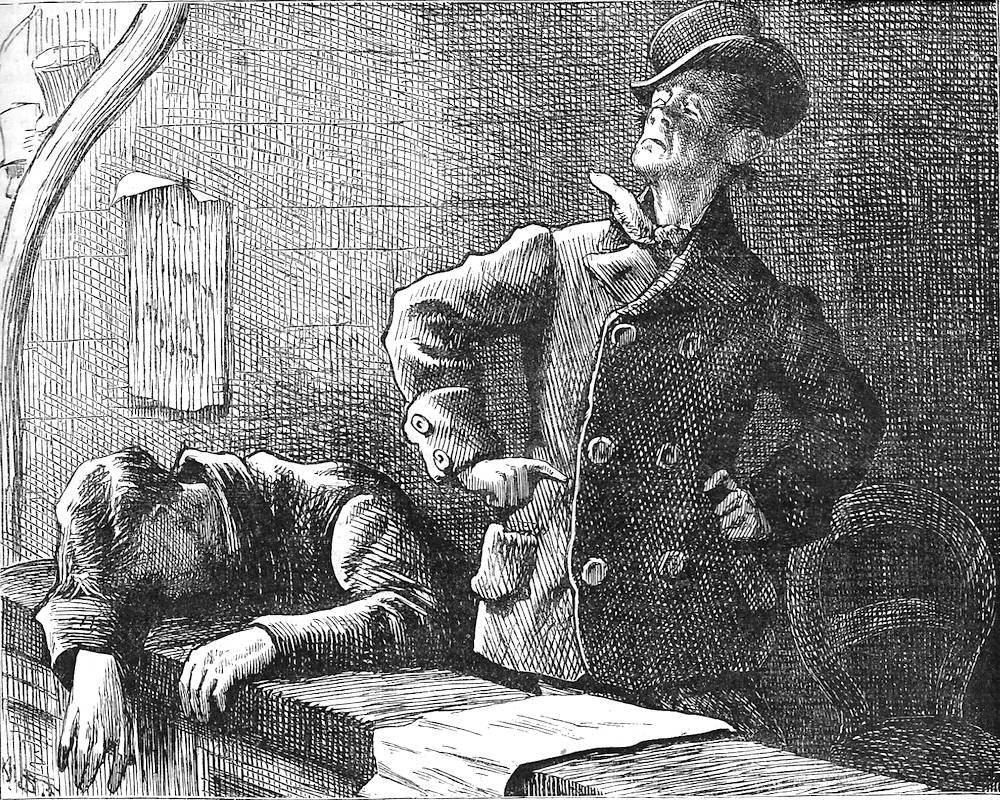

All these taunts Mr. Thomas Potter received with supreme contempt by A. B. Frost, in Charles Dickens's Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day People and Every-day Life, Pictures from Italy, and American Notes (1877), Section III. "Characters," Chapter XI: "Making a Night of It," p. 191. Wood-engraving, 4 ⅛ by 5 ⅛ inches (10.5 cm high by 13 cm wide), framed. Whereas George Cruikshank in the original anthology merely used the illustration Making a Night of It (1836) to introduce the principal characters in the context of a working-house playhouse, Frost has returned to Dickens's principal intention, satirizing the character of a young clerk who goes from bad to worse over the course of the evening (and early morning) on Quarter Day. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliographical Information

The sketch originally appeared in Bell's Life in London (18 October 1835) as "Scenes and Characters No. 4." Neither Fred Barnard (1876) nor Harry Furniss (1910) provided an illustration for this penultimate of the sketches in the "Characters" section, the former artist preferring to realise the lively group scene in The Prisoners' Van. The 1876 and 1877 Household Editions of Dickens's Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People contain only a single wood-engraving between them to illustrate this character sketch, namely Frost's study of the belligerent clerk in the theatre.

Passage Illustrated: Thomas Potter's Defiance in The City Theatre

Such was the quiet demeanour of the unassuming Smithers, and such were the happy effects of Scotch whiskey and Havannahs on that interesting person! But Mr. Thomas Potter, whose great aim it was to be considered as a ‘knowing card,’ a ‘fast-goer,’ and so forth, conducted himself in a very different manner, and commenced going very fast indeed — rather too fast at last, for the patience of the audience to keep pace with him. On his first entry, he contented himself by earnestly calling upon the gentlemen in the gallery to "flare up," accompanying the demand with another request, expressive of his wish that they would instantaneously ‘form a union,’ both which requisitions were responded to, in the manner most in vogue on such occasions.

"Give that dog a bone!" cried one gentleman in his shirt-sleeves.

"Where have you been a having half a pint of intermediate beer?" cried a second. "Tailor!' screamed a third. 'Barber’s clerk!" shouted a fourth. "Throw him O—VER!" roared a fifth; while numerous voices concurred in desiring Mr. Thomas Potter to "go home to his mother!" All these taunts Mr. Thomas Potter received with supreme contempt, cocking the low-crowned hat a little more on one side, whenever any reference was made to his personal appearance, and, standing up with his arms a-kimbo, expressing defiance melodramatically. Chapter XI, "Making a Night of It," p. 191]

Commentary: Thomas Potter to a "T"

Thus we encounter A. B. Frost's depiction the supercilious Thomas Potter, drunk in the balcony of the City Theatre on Quarter Day with fellow clerk Robert Smithers, on the same page as we encounter the passage illustrated. Smithers, who has passed out under the influence of Scotch and water, Havana cigars, and "a pot of the real draught stout" (190) is not so much a person as an object, and Potter is not looking at him, but down to the main auditorium from which his detractors hurl insults in an effort to shut him up. Frost has paid strict attention to Dickens's earlier description of Potter's hat and coat, as he depicts Potter's drunken defiance of other theatre patrons. What initially appears to be the table at which Smithers has passed out is the edge of the balcony: "embellishing theatre by falling asleep with his head and both arms gracefully drooping over the front of the boxes" (190). Frost indicates the wall of their box by showing the several gentlemen in the next box (far left). He has also depicted both Smithers' conventional fashions and Potter's peculiar mode of dress precisely:

The peculiarity of their respective dispositions, extended itself to their individual costume. Mr. Smithers generally appeared in public in a surtout and shoes, with a narrow black neckerchief and a brown hat, very much turned up at the sides — peculiarities which Mr. Potter wholly eschewed, for it was his ambition to do something in the celebrated ‘kiddy’ or stage-coach way, and he had even gone so far as to invest capital in the purchase of a rough blue coat with wooden buttons, made upon the fireman’s principle, in which, with the addition of a low-crowned, flower-pot-saucer-shaped hat, he had created no inconsiderable sensation at the Albion in Little Russell-street, and divers other places of public and fashionable resort. [190]

George Cruikshank's Making A Night of It from Sketches (1836).

In the sketch, the careful observer of London middle-class life, manners, and mores once again presents a portrait of young urbanites breaking the restraints of their boring jobs and stifling lifestyle to behave outrageously — indeed, Mr. Thomas Potter behaves so badly at The City Theatre that even the unruly working-class audience demands that he and his comatose companion be ejected — and the pair suddenly find themselves in the middle of the street. Although Dickens focuses on the clerks and does not indicate that anybody else is in their box, Cruikshank, perhaps drawing the scene from life, includes others watch Potter's performance aghast. Frost is far more realistic in his contrasting studies of the inebriated clerks, and places no one else in their box.

A young bourgeois's idea of a "night of it" in London of the 1830s on "quarter-day" (that is, the day once every three months on which government clerks such as John Dickens were paid) apparently included a large meal of chops and pickled walnuts, washed down by beakers of Scotch whiskey and followed by a visit to a working-class theatre to interrupt the performance with taunts and derogatory comments, as one sees in Pip's hilarious visit to the theatre to see the former village clerk, Mr. Wopsle, in Hamlet, in Great Expectations, Chapter 30.

Frost may have selected the moment illustrated from studying the original Cruikshank illustration, Making a Night of It. However, whereas Cruikshank emphasized the somewhat disreputable audience and its unseemly conduct as suggested by Dickens's description of its behaviour, but not improbably "drawn from life." In all likelihood, the venue which Cruikshank had in mind was The City Theatre, a disused club in Grub Street converted into a theatre in 1829; it later became The Pantheon, and saw performances by the celebrated Edmund Kean in 1831. Shortly after Dickens wrote this sketch, the theatre closed, and became a warehouse.

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicholas; Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens: Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Bratton, Jacky. ""Theatre in the 19th c." British Library Newsletter: Discovering Romantics & Victorians. Web. Posted 15 March 2014. Accessed 18 April 2019.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z. The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. "Characters," Chapter 11, "Making A Night of It," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 198-202.

Last modified 18 April 2019