Hardy aptly named the intense investigation of upper-middle class marriage and conflicting aspirations "An Imaginative Woman," since that title focuses the reader's attention on Ella Marchmill's unrealized artistic yearnings and contrasts her to her singularly unimaginative, prosaic husband. This theme appears again in Hardy's work, and if he had muted the subtheme of the literary rake's being punished by circumstances in "On the Western Circuit," he might have as easily used the title "An Imaginative Woman" for that story in connection with the fate of Edith Harnham, the simple-minded maid's employer and romantic letter-writer. However, Edith's unfulfilled emotional life is less bohemian and more conventionally romantic in its imaginings than Ella's. As in so many if Hardy's stories, conventional marriage proves an imposition to both partners, but the problems of marital discord increase ten-fold if the woman is "imaginative." Had Hardy placed less emphasis on the rake punished by circumstances and more on the intense inner life of Edith Harnham, he might well have entitled "On the Western Circuit" "An Imaginative Woman" instead. The husband and the poet are one-dimensional figures alongside the titular character in the 1893 story published in April 1894 in the Pall Mall Magazine.

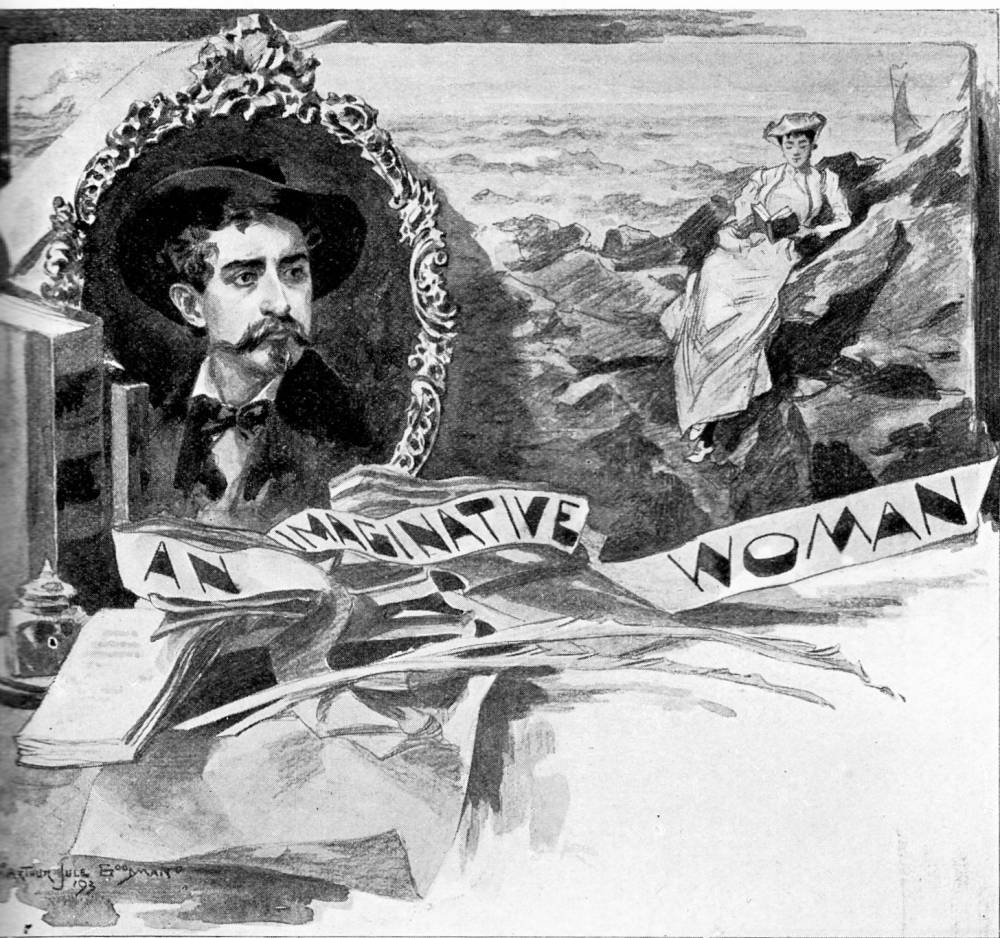

The fine illustrations by Arthur Jule Goodman (-1926) consist of an illustrated headpiece, six plates ranging in size from a third of a page to a full page, and ornamental initial letter "W" (this initial letter coincidentally being the first in the husband's Christian name). Ella Marchmill is initially depicted reading, Robert Trewe in a head-and-shoulders portrait study, and William Marchmill in leisure suit and cap, his back towards the reader. The only secondary characters depicted are the landlady, Mrs. Hooper ("I know his name very well; . . . and his writings." 954) with Ella in what had been the bachelor's back sitting-room, and Ella's fourth child as a toddler (uncaptioned, 969) with his father, who erroneously detects a facial resemble to the poet.

Each of the three principals in the romantic triangle is in a sense incomplete or not thoroughly revealed visually. Even the most frequently occurring character, Ella Marchmill, who appears in six illustrations (including one in which she appears alone), is introduced in the letterpress as "Mrs. Marchmill" (951), an extension of her husband William (who is introduced in the opening line) without her own Christian name. The illustration in which she appears by herself is significant in that her tracing the writing on the wall behind her ("Then she scanned again . . . the half-obliterated penciling on the wall." 961) implies the presence of the dead poet. Only the headpiece depicts her entirely free of the roles of wife and mother.

In the headpiece, Robert Trewe is (except for head and shoulders) without body; he possesses a romantic, cavalier-like face, affecting a Van Dyke beard, abundant moustache, and wide-brimmed hat, in contrast to William Marchmill's mere cap in the second illustration and businessman's top hat in the sixth. Goodman consistently depicts Ella's husband full-length and interacting with other characters: with Ella herself (plates 2, 4, and 6), and with the child in whose face he erroneously traces the features of the dead poet (plate 7). Trewe's informing presence is implied in plate 4, in which Ella admires herself in the poet's macintosh, and again in plate 6, lying in the grave that occupies the centre of the picture, the space between the standing, accusatory husband and the kneeling, startled wife. She is indeed becoming one with "John Ivy" (Trewe's pseudonym) in that she clings to the ground under which her imaginary "Trewe" beloved lies, slain by his own hand in a depressive fit. In "Enter a Dragoon" (1900), contend Gilmartin and Mengham, "The ivy [on the dead beloved's grave] symbolizes attachment, fidelity, constancy, all translated into forms of self-deception by disclosure of another narrative" (128); here, there is no other genuine narrative of infidelity, but the scene lays the basis for one in William Marchmill's imagination. Appropriately, Trewe is present in the text as text and in the illustrations as a visual symbol, "a photograph . . . in the ornamental frame on the mantlepiece" (959) in Ella's bedroom, a seductive talisman that works upon Ella's imagination in the fifth plate.

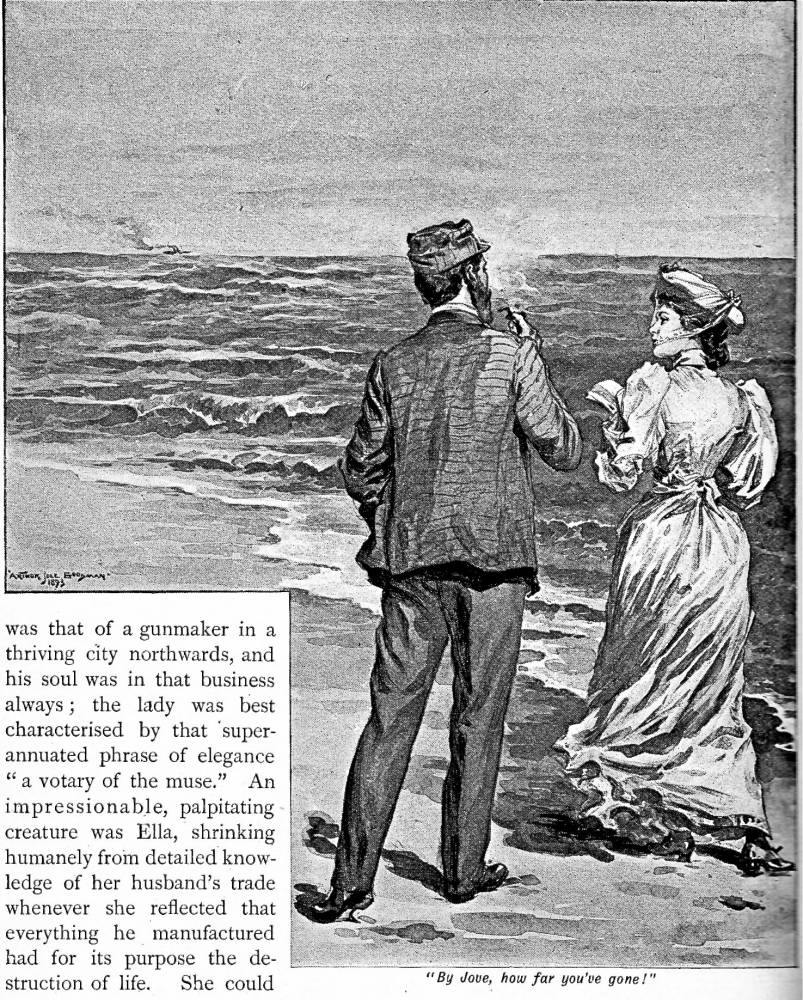

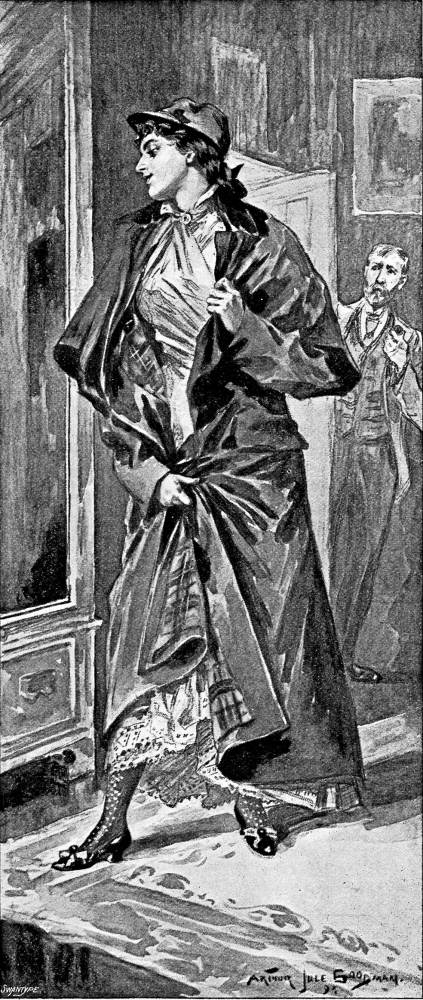

In contrast to the self-absorbed Ella, who dreams of the poet waking and sleeping (but only as a projection of her own poetical, intellectual, and Bohemian aspirations) and admires herself in his position (plates 4 and 5), translating her imaginative self-identification with him into a physical synthesis, the practical, is the active, outgoing William Marchmill. To emphasize his real but often ignored or minimized presence in Ella's emotional life, Goodman represents him as a full-bodied figure in three of his four appearances. Initially a mere pillar, his back to us, he acquires interest in the reader's eyes through his strongly felt emotions of jealousy in his last three appearances.

If the headpiece is in essence an overview of the story, then, despite his frequent appearances in the seven illustrations and scenes in the letterpress, William Marchmill must have seemed far less important than the object of Ella's adolescent infatuation. For the sake of continuity and emphasis, Goodman has Ella in the same dress throughout, except for the scene in which she muses on the pencillings on the wall (p. 961), and she wears the same hat in her first two appearances. The implied comraderie of husband and wife on the beach ("By Jove, how far you've gone!" 952) proves deceptive, for lost in a textual "reverie" (951) she has wandered far down the beach without paying attention to her children and the nurse, not depicted since Hardy tells us they are "considerably farther ahead" (951). The second full illustration shows apparent unanimity between the Marchmills, but the seeds of marital discontent are already present.

Kristin Brady interprets the theme of "An Imaginative Woman" in its revised state as the lead story for Life's Little Ironies (1912) as

the futility of imagining that life will conform to private dreams. Its plot is a carefully wrought inversion of the conventions of sentimental fiction and drama: the gradual building up of romantic expectations is met not by happy fulfilment but by disappointment and regret. Ella Marchmill . . . is at once a victim of circumstances and the builder of her own unhappy fate. Her inner life, like that of many of Ibsen's heroines, is made up of conflicting forces: romantic fantasizing and the practical business of living; intellectual and physical passion; conjugal, maternal, and Platonic love. [98]

However, to assert that the story's "subject is the failure of a nineteenth-century middle-class marriage" (98) is not merely to over-generalize or to make Hardy into an English Ibsen; rather, to lay the blame for marital blame equally on Ella and William Marchmill is to deny the original periodical version's overall effect. The 1894 story and its illustrations largely exonerate the practical and active husband, even though he all too often seems "oblivious to her emotional needs" (99).

The third illustration takes us further into Ella's constructed world of books and papers, in contrast to the natural world of the second plate which is William's appropriate arena. Books are carelessly strewn across the floor and writing desk, as well as piled irregularly on the shelves behind Ella, as if to imply the mental state of the previous occupant. "Herself the only daughter of a struggling man of letters" (951), Ella feels a natural (perhaps even Freudian) affinity for Trewe. We wonder precisely where Ella in this illustration is looking, for her gaze is directed neither to the book she holds nor to Mrs. Hooper; rather, in responding to just having read "the owner's name written on the title-page" (954) she seems to be conjuring up an image of the previous occupant in her mind's eye, integrating her experience of the room and her experience of Trewe through memory of his texts as she attempts to construct a picture of him reading and writing in this very room. Her legs parallel the one belonging to the writing desk, as if she is one with it, the object on which Trewe has written. Mrs. Hooper, in a dark gown and with sleeves rolled up, contrasts the figure of Ella in Goodman's third illustration, for she represents the mundane reality of the work-a-day world; to her, Trewe is merely a young man with too many books and not enough income for cutting a figure in the world beyond this little study.

The fourth illustration is pivotal in the process of Ella's identifying herself with Trewe and of her husband's later misreading of her relationship with Trewe. The upshot of her having discovered that she has taken possession of Trewe's study is that she withdraws from outer world, "possessed by an inner flame which left her hardly conscious of what was proceeding around her" (957), as in the headpiece's thumbnail of her. Enacting her fancy of becoming an established poet like Trewe, she hopes wearing the macintosh that the children stumble upon will "inspire" with his "glorious genius" (957). Like her children, she is playing a game when she dons the "mantle of Elijah" (moment realized, p. 957; illustration, p. 958). In Goodman's fourth illustration she is so self-absorbed in studying her face inside Trewe's clothes that she fails to apprehend her husband's arrival. The artist's focus here is not the image Ella is admiring, but the contrasting expressions and attitudes of husband (left, rear) and the foregrounded wife. The plate is a conflation of two separate and distinct textual moments, for the caption points to Ella's talking to herself as she sees herself in the raincoat and waterproof cap, but the arrival of her husband occurs when, the initial sense of elation of "wearing" Trewe having past, "The consciousness of her weakness [as a creative intellect] beside him made her feel quite sick" (957). Already as her husband enters she is starting to take off the cap and coat. The picture, thus combining the discrete moments, shows Ella not yet conscious of her "weakness" and blushing at having been caught by her husband thus engaging with her image of Trewe.

That process, although interrupted by William's unexpected appearance, continues into the fifth plate, "Then she scanned again . . . the half-obliterated penciling on the wall" (moment realized, p. 960; facing picture, p. 961). We encounter Goodman's interpretation of the moment just minutes before encountering it in the text, so that we are left to wonder for almost a page about the significance of the "penciling" (more verbal than nominal in force, and pluralized only in the letterpress) that she is so intently studying on the wall behind her bed. Particularly telling is the prominence that Goodman has accorded the books and Ella's bedside table, and the marginalized location of Trewe's framed photograph on the coverlet at the very bottom of the bed and barely recognizable as such, perhaps because the illustrator conceives of Ella's being infatuated not so much with the man's face as with his texts. We have visual continuity in Ella's face, but a discontinuity in her hair being untied. In this highly private moment, the details of the bedroom are indistinct, except for the bedstead; she holds up her candle to read Trewe's words, and has not yet extended her own arm to emulate his posture. While the free indirect discourse of the narrative penetrates Ella's thinking about Trewe, the image is an objectified version of this powerful scene. The artist captures the opening of Ella's reverie, and leaves the letterpress to explore it.

The last pair of images are separated from the previous five by six full pages of letterpress, during the course of which Trewe has committed suicide and Ella has denied Will's accusation that her relationship with the dead poet "didn't go far" (967) after he has caught her in the cemetery. Thus, the full-page illustration captioned "He . . . beheld a crouching object beside a newly made grave" (968) occurs after we have already encountered the moment textually. At least, Goodman has humanized the "object" in his illustration to present Ella's perspective as well as her husband's.

Left to right: (a) . (b) . [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

The late afternoon fall scene at the graveside transpires back in the Wessex seaside resort of Solentsea, to which first Ella and then William Marchmill travel by rail; however, since he travels by a fast train and she by a slower, he catches up to her shortly after her arrival in the cemetery. "Although it was not late, the autumnal darkness had now become intense" (967), rendering this time of day and season so appropriate for the husband's confronting his wife on the very grave of the man whom he suspects was her lover. Gilmartin and Mengham contend that "The closest that Ella gets to a physical reality in her relationship with Trewe is in tracing the outlines of his writing on the wall above her bed" (114); in fact, the closest she comes to Trewe is, as Goodman underscores, is lying on his grave, again imitating his posture and enacting a standard romantic role, that of the living Juliet to Trewe's dead Romeo in the Capulet monument in the closing scene of Romeo and Juliet.

In the gloom of the late afternoon, William Marchmill at first fails to see clearly even his way among the serpentine paths; then, he fails to see a person on "the newly made grave" (967). However, once she has suddenly arisen from her supine posture, he recognizes her, even calling her by the pet-name "Ell," even as he "indignantly" reproves her for "Running away from home" and therefore from her domestic responsibilities. However, he specifically denies that he is "jealous of this unfortunate man" (967). All of this has transpired on the page previous to the periodical version's only full-page illustration; in fact, as she dies at the bottom of that page, she neither 'admits' nor 'denies' her husband's suggestion that she is still thinking "about that — poetical friend" — he dash implying that William had momentarily been tempted to describe Trewe as her "lover."

Already in the penultimate illustration Ella is rising from the grave in the right foreground as her husband gestures towards her and she points at the grave. The scene is played out against a backdrop of white tombstones and black, leafless trees, the characters' costumes repeating the black-white dichotomy. The situation morally, however, is hardly black-and-white; despite the accusatory gesture, Ella is not guilty of any physical act of adultery, even in her imagination. Goodman has given Ella a travelling veil and dark cape, but the white dress she wears beneath it resembles the dress she wears in the opening plates. Significantly, Goodman has not depicted her in deep mourning, for even she realizes that her relationship with the deceased is at best one of shared emotional and artistic perceptions. The coat, tie, jacket, and trousers worn by her husband, repeated in the final plate for the sake of visual continuity, nevertheless emphasize the husband's bourgeois status and business success. Indoors and therefore hatless in the final illustration, he is a widower with responsibility for bringing up a child he does not believe is his. Between these two illustrations (the latter a tailpiece in that it has been placed after the author's name), Ella dies without being able to reveal the limited extent of her harmless infatuation with the poet and leaving her husband suspecting from her tone and manner that she had committed adultery.

Thus, the scene depicted in the cemetery includes qualities associated with traditional husband-and-wife "caught-in-the-act" adultery scenarios, such as "The Screen Scene" in Richard Brinsley Sheridan's The School for Scandal (1777) on stage and "The Letter" in Augustus Egg's narrative-pictorial sequence Past and Present (1858) in the fine arts. Goodman's husband is not, like either Sir Peter Teazle or Egg's reader of the letter, momentarily stupefied, and this scene is neither pure comedy nor straight melodrama. Although neither angry nor despondent, William Marchmill is accusatory and indignant as he gestures towards the other man. Ella Marchmill cringes before the father of her children, embarrassed and unable to defend herself in speech, so ludicrous is her position. In this illustration as in the last, Goodman emphasizes the deceptive nature of appearances; the irony is dramatic since the reader knows the truth about Ella's arm's-length infatuation, but her husband (like the reader who constructs a narratively only from Goodman's illustrations and without regard to Hardy's letterpress) remains deluded by the circumstantial evidence of adultery, including a previously unnoticed facial resemblance between the child and the poet's photograph, and the colour of the toddler's hair and that of the lock of the poet's hair that Ella had innocently enough acquired. Ironically, Hardy remarks parethetically, immediately above the tailpiece depicting the precise moment of misapprehension, he had never before really thought there was any resemblance. He regards the child not by the clear light of day but by the distorting light of a desk-lamp in a darkened room (recalling Ella's tracing Trewe's pencillings), and ha — not an epiphany, for that would imply a sudden, dazzling perception of a fundamental self-truth — a moment of intense rejection, suggesting that he, the spectre of adultery raised by his imagination, will now perpetuate the careless parent role of his dead wife. Relentlessly, as in Jude the Obscure, Hardy once again denies the reader any form of romantic or emotionally satisfying closure. Thus, in her study of Hardy's short fiction Brady finds Hardy's relocating the story to the very beginning of Life's Little Ironies highly appropriate, since in volume form it serves as an effective induction to a short story anthology thematically organized to inculcate the notion that "imagined happiness always fails to be realized in conventionally sentimental terms" (104).

Bibliography

Brady, Kristin. The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy. London and Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1982.

Hardy, Thomas. "An Imaginative Woman." The Pall Mall Magazine 2.12 (April 1894): 951-69.

Last modified 1 June 2014