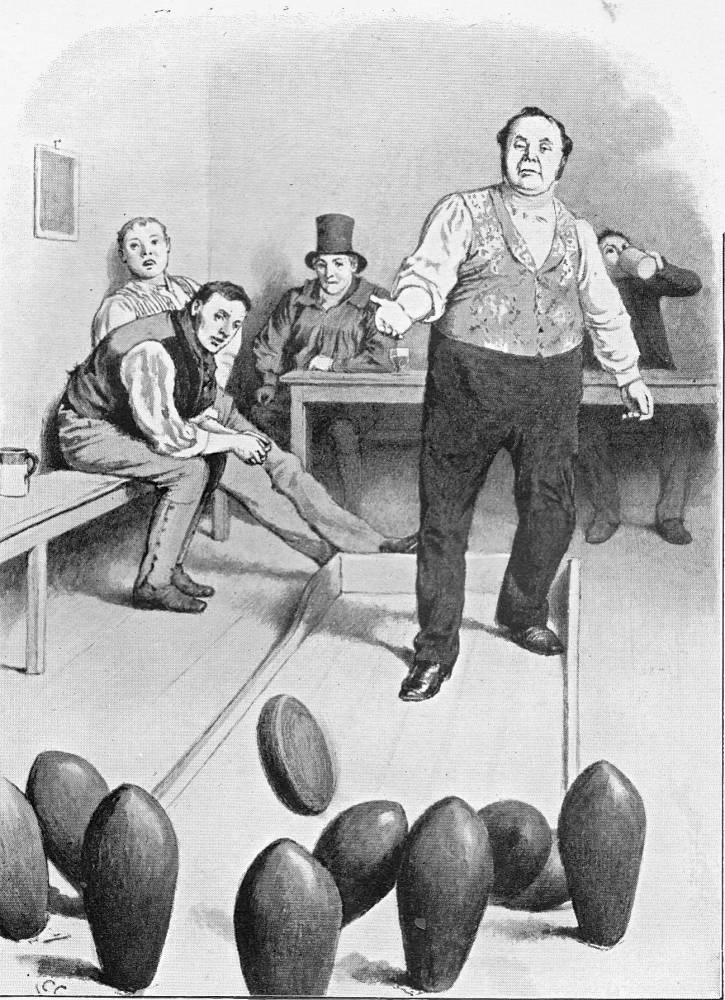

Sir Joseph Bowley at Skittles

Charles Green

1912

14.7 x 11.1 cm, vignetted

Dickens's The Chimes, The Pears' Centenary Edition, II, 96.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.].

Passage Illustrated

There was to be a great dinner in the Great Hall. At which Sir Joseph Bowley, in his celebrated character of Friend and Father of the Poor, was to make his great speech. Certain plum-puddings were to be eaten by his Friends and Children in another Hall first; and, at a given signal, Friends and Children flocking in among their Friends and Fathers, were to form a family assemblage, with not one manly eye therein unmoistened by emotion.

But, there was more than this to happen. Even more than this. Sir Joseph Bowley, Baronet and Member of Parliament, was to play a match at skittles — real skittles — with his tenants! ["Third Quarter," 97, 1912 edition]

Commentary

The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang An Old Year Out and a New Year In (1844) provides no equivalent for this illustration of Sir Joseph's playing the traditional game of skittles with his tenants, by their garb, farmers. In fact, this scene does not occur within the text, but is only projected, as it were, since the bowling match is scheduled to transpire as the acme of Sir Joseph's paternalistic celebration of a traditional New Year's Day on his estate. Green has perhaps chosen the scene to represent Dickens's satire of the Young England Movement, a nostalgic initiative to restore the "good old days" of the sharply defined feudal relationships between the upper and lower classes. As a political radical and staunch supporter of Reform both electoral and social, Dickens was incensed at this Conservative movement's desire to turn back the clock on parliamentary and social reforms, because he earnestly believed that "the good old times" vaunted by the "red-faced gentleman" (42) who is part of Alderman Cute's entourage were neither "grand" nor "great," except for the privileged few. Sir Joseph's contemplating the restoration of the old custom of playing skittles with his tenants is another remnant of Dickens's cancelled satire on The Young England Movement, an ultra-Conservative, Sir Benjamin Disraeli-led splinter group of young, aristocratic Members of Parliament, educated in the post-secondary institutions that were upper-class bastions of privilege, Eton and Cambridge. Their imaginative but simplistic cure for the general dissatisfaction of the labouring classes so evident in the 1840s was to restore power to the Church, the aristocracy, and the monarchy, while severely limiting the powers of the middle-class-dominated House of Commons. According to Michael Slater, Young England believed that "the natural protectors of the poor — a noblesse oblige aristocracy and an almsgiving church — needed to be recalled to their duties" (247).

The closest that the original program of illustration comes to the noblesse oblige of Sir Joseph's skittles competition is the scene of the drawing party by Clarkson Stanfield, Will Fern's Cottage ("Third Quarter," p. 120), in which the picture celebrates a picturesque cottage amidst a traditional English landscape, but which is undercut by the social critique of Dickens's text. The full caption of Green's illustration of the Poor Man's Friend condescending to socialise with his tenants is "Sir Joseph Bowley, Baronet and Member of Parliament, was to play a match at skittles — real skittles — with his tenants" (96), the full text appearing immediately opposite the full-page lithograph. Green has positioned the viewer at the end of the bowling alley as the wooden skittle hurtles towards the nine pins. The bowler in elegant flowered waistcoat and shirt sleeves contrasts in size and fashion the four tenants of the yeomanry in the background. Two of the spectators wear agricultural linen smockfrocks, and two drink Sir Joseph's health with either beer or cider. Since Dickens does not actually describe such a scene, the illustrator has presumably constructed it from a scene he has witnessed or imagined as occurring in the Home Counties, or perhaps in that most traditional county of all, Dorset, the county, according to Michael Slater “where the peasantry existed in the utmost squalor and poverty. See a letter signed 'A Dorsetshire Landlord' in Lloyd's Weekly London Newspaper (28 April 1844), which asserted that if the farm-labourers' condition were not swiftly ameliorated, it 'must . . . produce a revolution not less frightful than that which France has been subjected to'” (266n30).

In reviewing the proofs in London in December 1844, Dickens changed Will Fern's county from Hertfordshire to Dorset, where recent rick-burning and assaults on bridges were obvious signs of proletarian discontent, reflected in Thomas Hood's November 1844 satirical poem "The Lay of the Labourer" in Hood's Magazine. Slater notes that the Annual Register published in 1844 reported over a hundred cases of arson in the counties during the previous year (note 26, p. 265).

Other illustrators have generally not dwelt upon this aspect of Dickens's social critique, but Fred Barnard's "Whither thou goest, I can Not go; where thou lodgest, I do Not lodge; thy people are Not my people; Nor thy God my God!" (citing "The Book of Ruth") depicts a haggard Will Fern, but recently released from prison, denouncing Sir Joseph Bowley and his dinner guests as callous, unfeeling aristocrats who do not care about the welfare of the workers whose labouring in the fields has made these aristocrats rich and powerful for generations. There is no hint of the impending rebellion in Green's large-scale lithograph of "The Good Old Times."

Illustrations from the first edition (1844) and the British Household Edition (1878)

Left: Maclise's scene of Trotty entertaining the two travellers from Dorset, Trotty at Home. Centre: Barnard's Gothic interpretation of Will's denouncing Sir Joseph and his guests, "Whither thou goest, I can Not go; where thou lodgest, I do Not lodge; thy people are Not my people; Nor thy God my God!" Right: Right: Stanfield's picturesque study of a Dorset cottage and cottager being sketched by an aristocratic party, Will Fern's Cottage (1844).

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Chimes. Introduction by Clement Shorter. Illustrated by Charles Green. The Pears' Centenary Edition. London: A & F Pears, [?1912].

_____. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang An Old Year Out and a New Year In. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Daniel Maclise. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1844.

_____. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang An Old Year Out and a New Year In. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Daniel Maclise. (1844). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978. 137-252.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated byHarry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated byE. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-118.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Welsh, Alexander. "Time and the City in The Chimes." Dickensian 73, 1 (January 1977): 8-17.

Victorian

Web

Illustration

Charles

Green

The Chimes

Next

Created 7 April 2015

Last modified 11 March 2020