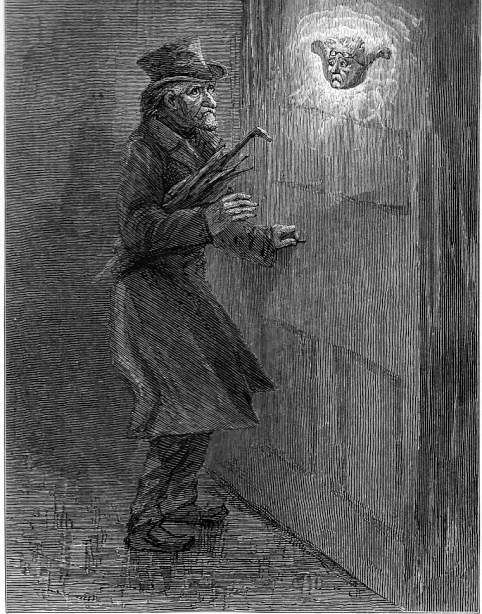

Scrooge's knocker

Charles Green

c. 1912

7.2 x 5.5 cm, vignetted

Dickens's A Christmas Carol, The Pears' Centenary Edition of The Christmas Books, I, 29.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Charles Green —> A Christmas Carol —> Charles Dickens —> Next]

Scrooge's knocker

Charles Green

c. 1912

7.2 x 5.5 cm, vignetted

Dickens's A Christmas Carol, The Pears' Centenary Edition of The Christmas Books, I, 29.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Now, it is a fact, that there was nothing at all particular about the knocker on the door, except that it was very large. It is also a fact, that Scrooge had seen it, night and morning, during his whole residence in that place; also that Scrooge had as little of what is called fancy about him as any man in the city of London, even including — which is a bold word — the corporation, aldermen, and livery. Let it also be borne in mind that Scrooge had not bestowed one thought on Marley, since his last mention of his seven years' dead partner that afternoon. And then let any man explain to me, if he can, how it happened that Scrooge, having his key in the lock of the door, saw in the knocker, without its undergoing any intermediate process of change — not a knocker, but Marley's face.

Marley's face. It was not in impenetrable shadow as the other objects in the yard were, but had a dismal light about it, like a bad lobster in a dark cellar. It was not angry or ferocious, but looked at Scrooge as Marley used to look: with ghostly spectacles turned up on its ghostly forehead. The hair was curiously stirred, as if by breath or hot air; and, though the eyes were wide open, they were perfectly motionless. That, and its livid colour, made it horrible; but its horror seemed to be in spite of the face and beyond its control, rather than a part or its own expression.

As Scrooge looked fixedly at this phenomenon, it was a knocker again.

To say that he was not startled, or that his blood was not conscious of a terrible sensation to which it had been a stranger from infancy, would be untrue. But he put his hand upon the key he had relinquished, turned it sturdily, walked in, and lighted his candle.

He did pause, with a moment's irresolution, before he shut the door; and he did look cautiously behind it first, as if he half-expected to be terrified with the sight of Marley's pigtail sticking out into the hall. But there was nothing on the back of the door, except the screws and nuts that held the knocker on, so he said "Pooh, pooh!" and closed it with a bang.["Stave One: Marley's Ghost," 29-30]

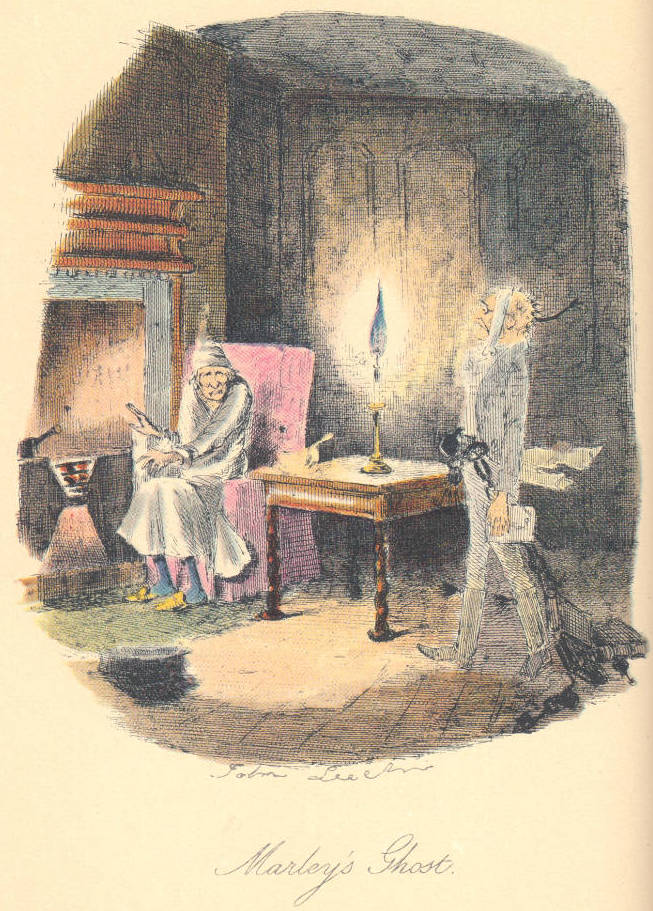

John Leech in the original edition focussed not on this preliminary warning of Marley's arrival from the depths of Scrooge's subconscious and the grave, but rather on the arrival of the chain-dragging spirit himself several pages later. In fact,Sol Eytinge, Junior, in his twenty-fifth anniversary Christmas Carol, seems to have been the first illustrator to consider the transformation scene as worthy of pictorial comment; certainly it is important in that it marks the point at which Scrooge departs from strict reality through a metaphysical portal into a world of vivid memories and terrifying nightmares. Few artists have had the opportunity to provide such a realisation, the other exception to this observation being Arthur Rackham in his 1915 tour de force. Both of the Household Edition illustrators, having the space for only a few illustrations, like Leech have chosen to show Scrooge's reaction to the Ghost's arrival as Scrooge sits, trying to get comfortable in front of a weak fire after the disturbing initial visitation. Neither Eytinge's realistic treatment, with Scrooge in a topcoat and carrying an umbrella, nor Rackham's study of the knocker itself in a simple pen-and-ink drawing captures the psychological dimension of Scrooge's confrontation with the metaphysical world — and neither possesses Furniss's abundant humour, although the expression on Marley's face in Rackham's line drawing suggests the ghost's dissatisfaction or discomfort with having materialised as a door-knocker.

The knocker as envisaged by Green is neither psychologically magnified nor animated, but resembles the actual door-knocker that Dickens had in mind and described, a knocker with a man's face rather than (as was usual) a lion's. It was the doorknocker on a house in eighteenth-century Craven Street that gave Charles Dickens the idea for one of the most memorable scenes in all of Dickens. T. W. Tyrell in "The 'Marley' Knocker" in the Dickensian (October 1924) has suggested that Dickens's transformation of bronze door-knocker into Marley's face was influenced by an unusual knocker with a man's face "that hung on the front door of No. 8 Craven Street when it was occupied by one Dr. David Rees in the 1840s" (cited in Guiliano and Collins, I: 841, and Hearn, Note 55, p. 70]. However, the unwanted attention the door received in the twentieth century has resulted in the owner's having it taken down and placed in a bank vault.

Left: Eytinge's scene of Scrooge's shock at seeing Old Marley's likeness on his own door, Marley's Face. Right: Leech's interpretation of the arrival of the shade of Scrooge's former partner, Marley's Ghost.

Left: Furniss's The Ghostly Knocker (1910), featuring a psychologically magnified version of the knocker. Right: Rackham's simple line-drawing of the dour-faced knocker, Heading to Stave One (1912).

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books, illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books, illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878. Vol. XVII.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. VIII.

_____. Christmas Books, illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. 16 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Created 28 July 2015

Last modified 29 February 2020