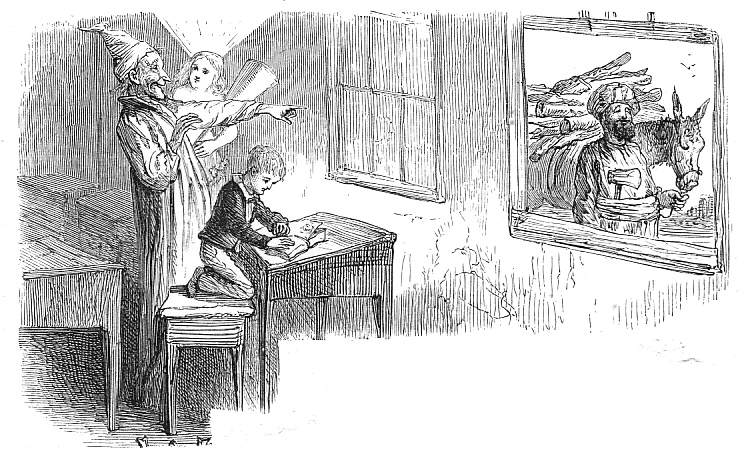

The Child Scrooge and His Sister

Charles Green

c. 1912

9.3 x 7.5 cm. vignetted

Dickens's A Christmas Carol, The Pears' Centenary Edition of The Christmas Books, vol. 1, page 54.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.].

Passage Illustrated

He was not reading now, but walking up and down despairingly. Scrooge looked at the Ghost, and with a mournful shaking of his head, glanced anxiously towards the door.

It opened; and a little girl, much younger than the boy, came darting in, and putting her arms about his neck, and often kissing him, addressed him as her "Dear, dear brother."

"I have come to bring you home, dear brother!" said the child, clapping her tiny hands, and bending down to laugh. "To bring you home, home, home!"

"Home, little Fan?" returned the boy.

"Yes!" said the child, brimful of glee. "Home, for good and all. Home, for ever and ever. Father is so much kinder than he used to be, that home's like Heaven! He spoke so gently to me one dear night when I was going to bed, that I was not afraid to ask him once more if you might come home; and he said Yes, you should; and sent me in a coach to bring you. And you're to be a man!" said the child, opening her eyes, "and are never to come back here; but first, we're to be together all the Christmas long, and have the merriest time in all the world."

"You are quite a woman, little Fan!" exclaimed the boy.

She clapped her hands and laughed, and tried to touch his head; but being too little, laughed again, and stood on tiptoe to embrace him. Then she began to drag him, in her childish eagerness, towards the door; and he, nothing loth to go, accompanied her.

A terrible voice in the hall cried. "Bring down Master Scrooge's box, there!" And in the hall appeared the schoolmaster himself, who glared on Master Scrooge with a ferocious condescension, and threw him into a dreadful state of mind by shaking hands with him. He then conveyed him and his sister into the veriest old well of a shivering best-parlour that ever was seen, where the maps upon the wall, and the celestial and terrestrial globes in the windows, were waxy with cold. Here he produced a decanter of curiously light wine, and a block of curiously heavy cake, and administered instalments of those dainties to the young people: at the same time, sending out a meagre servant to offer a glass of "something" to the postboy, who answered that he thanked the gentleman, but if it was the same tap as he had tasted before, he had rather not. Master Scrooge's trunk being by this time tied on to the top of the chaise, the children bade the schoolmaster good-bye right willingly; and getting into it, drove gaily down the garden-sweep: the quick wheels dashing the hoar-frost and snow from off the dark leaves of the evergreens like spray. ["Stave Two: The First of the Three Spirits," p. 52-53]

Commentary

The title in the "List of Illustrations," "The Child Scrooge and His Sister," is augmented by a quotation that serves as the picture's caption on page 54, although the schoolmaster with the brazen voice is nowhere evident in the illustration:

He produced a decanter of curiously light wine, and a block of curiously heavy cake. [based on text, p. 53]

Although Dickens's original illustrator, John Leech, did not develop a realisation of this significant moment from Scrooge's childhood, the early modern artist Arthur Rackham has provided a similar illustration to the passage that, in a Freudian sense at least, points the reader towards Ebenezer Scrooge's back-story, his father's rejection (which modern film adaptations imply that he suffered as a result of his mother's having died in childbirth). However, Rackham's illustration exploits the com,icx potential of the scene, whereas, as is consistent with the text, Green's intention is to generate pathos for Scrooge as a boy. His sole sibling, Fan, is smaller and younger than her brother as they are entertained by the head-master in his study .Whereas the 1867 Ticknor-Fields edition contains a headpiece for the second stave, a wood-engraving entitled The Vision of Ali Baba, vignette for "Stave 2. The First of the Three Spirits" that underscores young Scrooge's imaginative nature and social isolation, Green here notes how younger sister Fan intervened on her brother's behalf, entreating her father to permit the boy to come home for the holidays. Neither the illustration nor the text clarifies the nature of the father's animosity nor the boy's reception when he arrived home for the holidays.

Whereas Sol Eytinge, Jr., presents a cartoon-like, turbanned Ali Baba as a portrait and focuses instead upon Scrooge's joyful response, Green follows up his realisation of the visit from the imaginary characters from Scrooge's childhood reading with this picture of the "delicate creature" (54) who truly loved her brother. Green emphasizes these scenes from Scrooge's past in a way that Leech, with but a very limited number of scenes to draw, could not, showing merely Mr. Fezziwig's Ball as representative of a kinder, gentler time in the annals of business, a golden age from which capitalistic efficiency and the new 'money morality' prevent Scrooge from recapturing. In contrast, Green has provided six pictures to complement the second stave, showing Scrooge as a student in school, a beloved brother, and a young man in love whose suit was ultimately rejected because the golden calf of commerce had replaced the fiancee's image in his heart.

Green prettifies young Fan, dressing her in late Victorian girlish fashion, her extensive curls peeping out from under a stylish hat. The map behind the children establishes the setting as the head-master's office, although the settee is rather more elaborate than one might expect. Scrooge, dressed in the same suit as in the previous illustration showing him as a solitary reader, takes interest in what Fan has to say, so that the illustration suggests further conversation regarding the father's change of heart towards the boy. The picture is juxtaposed not against the passage it realizes, but against Scrooge's subsequent reminiscence that the delicate girl "had a large heart" (54) died young. Green renders her as charming and well-dressed, and genuinely interested in having a congenial relationship with her older brother. Until his partnership with accountant ("clerk") Jacob Marley and his romance with Belle (the subject of the ensuing illustration), little Fan was the most significant person in Scrooge's life.

Relevant Illustrations from the 1843, 1868, and 1910 Editions

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's scene of Scrooge's being visited by the figures from his beloved books, The Vision of Ali Baba. Right: John Leech's interpretation of Scrooge's attempting to suppress painful memories, Scrooge Extinguishes the First of The Three Spirits. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Left: Harry Furniss's The First of the Three Spirits (1910), featuring a psychologically introverted child and a country school in the mists of memory. Right: Arthur Rackham's more humorous scene from Scrooge's school days, He produced a decanter of curiously light wine, and a block of curiously heavy cake (1915).

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustration

Charles

Green

A Christmas

Carol

Next

Last modified 4 August 2015