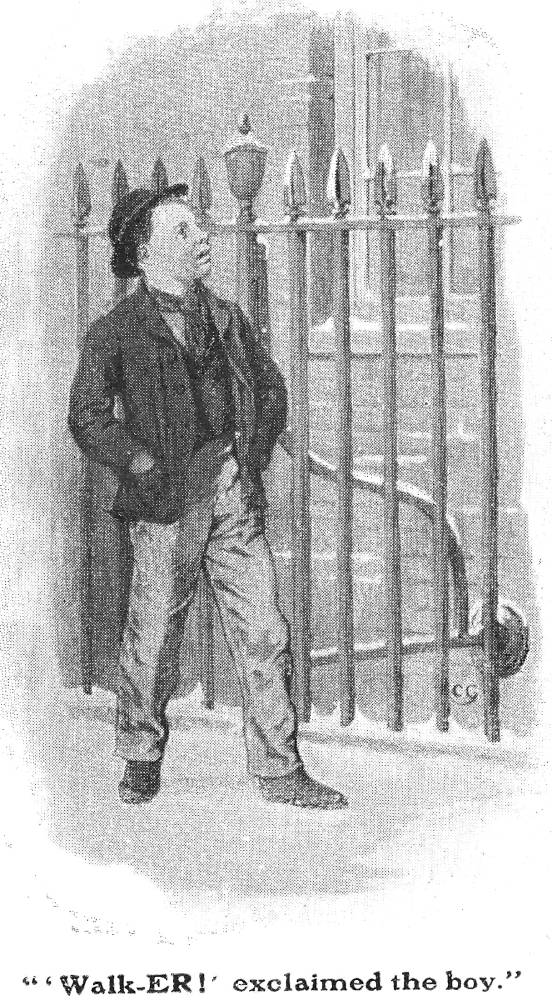

"Walk-ER!" exclaimed the boy.

Charles Green

c. 1912

8.5 x 4.8 cm. vignetted

Dickens's A Christmas Carol, The Pears' Centenary Edition of The Christmas Books, vol. 1, page 130.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.].

Passage Illustrated

"Do you know the Poulterer's, in the next street but one, at the corner?" Scrooge inquired.

"I should hope I did," replied the lad.

"An intelligent boy!" said Scrooge. "A remarkable boy! Do you know whether they've sold the prize Turkey that was hanging up there — Not the little prize Turkey: the big one?"

"What, the one as big as me?" returned the boy.

"What a delightful boy!" said Scrooge. "It's a pleasure to talk to him. Yes, my buck."

"It's hanging there now," replied the boy.

"Is it?" said Scrooge. "Go and buy it."

"Walk-ER!" exclaimed the boy.

No, no," said Scrooge, "I am in earnest. Go and buy it, and tell 'em to bring it here, that I may give them the direction where toi take it. Come back with the man, and I'll give you a shilling. Come back with him in less than five minutes, and I'll give you half-a-crown!"

The boy was off like a shot. ["Stave Five: The End of It," p. 129-131]

Commentary

The second of the five scenes that Green has included for the final stave is a vignette (integrated into the very dialogue it realises) intended to communicate how profoundly the visitations have affected Scrooge, who (textually at least) is now full of bonhommie rather than curt, anti-Christmas sentiment. His new attitude towards Christmas is signalled by his engaging in a dialogue with a passing boy, dressed as if going to church in his "Sunday clothes" (129). Punch cartoonist John Leech provided only a single image of the post-visitation Scrooge, but Green, with a much longer program of illustration, feels that the conversation between redeemed Scrooge and the kind of child he formerly dismissed is worthy of visual comment. The whole turkey-ordering episode, foregrounded to demonstrate Scrooge's social re-integration is curiously devoid of religious overtones, despite the street-boy's presumably being on his way to church. The stout iron bars of Scrooge's area railing immediately behind the incredulous boy, standing on the snowy pavement, implies Scrooge's former alienation, his rejection of anything not immediately associated with business and commerce.

The original illustrator, John Leech, included just one small wood-block engraving to demonstrate Scrooge's change of heart as an employer, Scrooge and Bob Cratchit, or The Christmas Bowl, but, of the other nineteenth-century illustrators of the novella, only Sol Eytinge, Junior in the 1868 Ticknor and Fields edition has devoted a significant proportion of his program to the new, improved Scrooge, showing him joyfully putting on his socks on Christmas morning and smiling broadly as he digs into his pocket to find the coins to pay the poulterer for the prize bird he intends to send anonymously to the Cratchits in The Prize Turkey. Green utilizes the detailing of the wrought-iron area railing to convince us of the reality of the new behaviour that signals Scrooge's social re-integration. Green has moved in for a close-up at street level of the boy, hands in his pockets to keep them warm, the plucky and street-smart Cockney "Boy Who Gets Turkey," (1984 film cast) or the "Boy Sent to Buy Turkey" (1951 film cast). Whereas the boy in scarf and cap is seen from Scrooge's aerial perspective in the 1951 and 1984 films, Green gives us the boy as seen by passersby, and shortly by Scrooge himself. In other words, the two illustrations of Scrooge and then of the boy, taken together, give the reader a sense of a genuine communication between the interrogative Scrooge from above and the boy below, responding in the language of the street, Cockney slang ("Hookee Walker" being proverbial for a bald-faced liar and, by extension, a "whopper" or enormous deceit, which the lad initially senses Scrooge's request to be; Michael Slater, citing noted Dickensian T. W. Hill, glosses "Walk-ER" as suggestive of "amused credulity," 261).

However, it is one thing to hire a boy and engineer the delivery of an anonymous gift — cash transactions not so very different from the kind that the businessman has been making most of his adult life — and quite another to apologise to another young man whom he has consistently rejected — his sister's son, Fred. As E. A. Abbey realised in the 1876 American Household Edition, the most important scene in this stave is his reconciliation with his nephew, "It's I. Your Uncle Scrooge! I have come to dinner. Will you let me in, Fred?". The turkey episode is, after all, merely another series of cash transactions, giving the lad a bonus of half-a-crown if he returns quickly with the poulterer's man, then buying the bird and sending it to Camden Town in a cab; this is generosity, but not contrition, because it is further evidence of Scrooge's operating the old dispensation, what the Chelsea Sage, Thomas Carlyle, terms "the cash nexus." Nevertheless, Scrooge's child-like wonder at the brightness of the cold, crisp morning, his joy at being alive after all, and his new-found ability to relate to children augur well for his rejoining the human family as "Uncle" Scrooge to that other significant child of the tale, Tiny Tim.

Images from the original (1843), the Ticknor & Fields (1867), and American Household Editions (1876) of the Reformed Scrooge

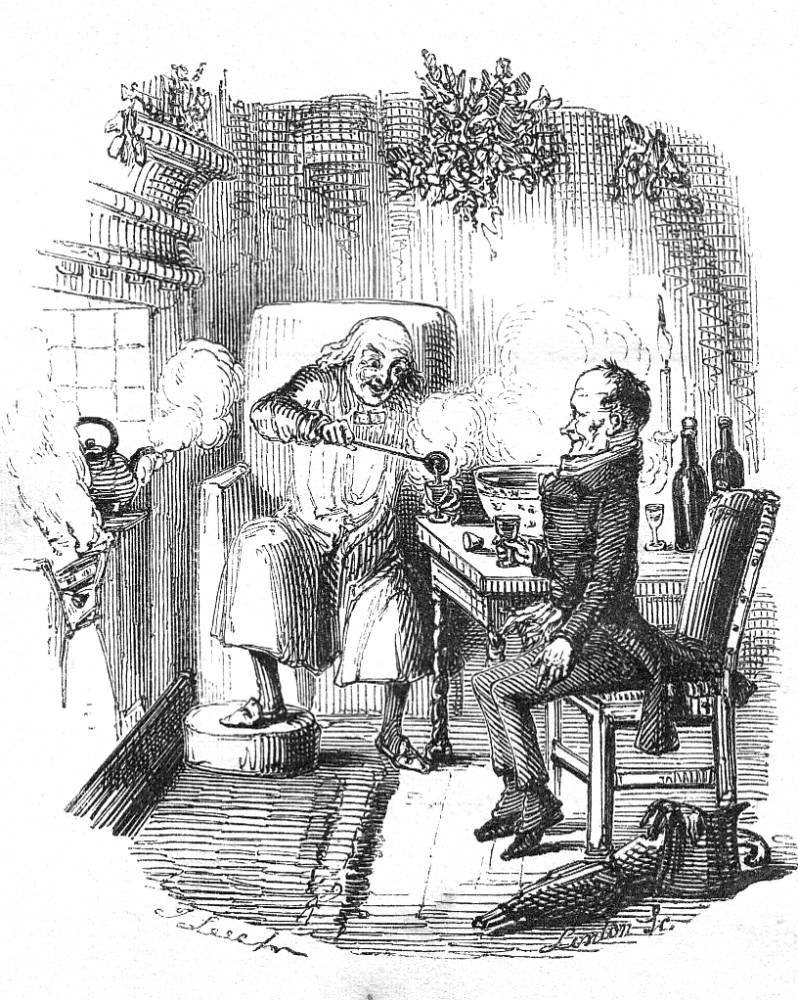

Left: John Leech's tailpiece of Scrooge and his employee sharing punch, Scrooge and Bob Cratchit, or The Christmas Bowl. Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's attempt to capture the reformed Scrooge's child-like ebullience, The Prize Turkey.

Above: E. A. Abbey's 1876 engraving of Scrooge's "mending fences" with his nephew, "It's I. Your Uncle Scrooge! I have come to dinner. Will you let me in, Fred?" [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

____. A Christmas Carol. With 27 illustrations by Charles Green, R. I. Pears' Christmas Annual. London: A & F Pears, 1892.

____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Victorian

Web

Illustration

Charles

Green

A Christmas

Carol

Next

Last modified 30 August 2015