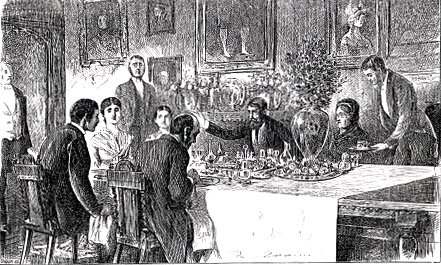

"Fine Old Screen, Sir!" [Luncheon in Castle de Stancy, Hosted by Paula Power] by George Du Maurier for Harper's New Monthly Magazine (1880). Plate 2 Thomas Hardy's A Laodicean.

Moving from the interior of a Baptist chapel to something more within Du Maurier's métier, the gathering of figures from high society in a great house, we encounter Paula Power surrounded by guests and servants. The backdrop contains five family portraits in the variety of styles and sizes delineated early in the second instalment: "Holbein, Jansen, and Vandyck; Sir Peter, Sir Godfrey, Sir Joshua, and Sir Thomas." The catalogue of de Stancy paintings in the long gallery (not the dining room, as in the plate) stamps the castle as a seat of patriarchy, of masculine authority. Among the portraits, women have identity only in so far as they are hanging by their husbands’ sides. While the male visages from the Elizabethan period through the eighteenth century have a common "nobility stamped upon them beyond that conferred by their robes and orders" in the text, Hardy categorizes the females depicted as "feeble and watery, or fat and comfortable." Paula, of course, as a modern woman falls into neither category.

The famous paintings, on which much of the action turns, appear in two drawings . . . , and for that Du Maurier is to be commended because the illustrations thus keep the novel's central conflict (of aristocratic privilege and the past, versus modern industry and self-help) alive in the reader's mind. [Jackson 126]

Du Maurier's rendition of these ancestral portraits here, however, is incidental and indistinct. Had he depicted the women's faces, Du Maurier could have offered a significant contrast to the youthful heroine seated at the head of the table. Since nobody sits at the other end of the table, she is markedly in loco hominis in a scene dominated by male figures (three diners and three servants). The printed text identifies the diners as Paula Power; her friend, Charlotte De Stancy (left of Paula at the table in the plate) seated beside her; the local architect and Somerset's professional rival from their first meeting, Mr. Havill (the bearded man, centre, gesturing towards the screen, off left); an elderly, dignified matron in black satin (Mrs. Goodman, Paula's chaperon); Mr. Woodwell, the Baptist minister, identifiable from the first plate by his balding head and distinctive side-whiskers (in the text, seated beyond the widow, but for convenience of conversation and to make the scene more compact, beside Somerset in the plate); and George Somerset, to the immediate right of Paula, who responds to Havill's remark about the screen. Du Maurier has provided the servants, not specifically alluded to in the text, and his signature (conspicuous on the table-cloth, down centre). He has chosen this scene in order to make Paula a continuing character, to introduce Somerset more closely, to provide continuity with the first plate through the faces of Paula and the minister, and to introduce Havill as one of the antagonists. We have yet to meet De Stancy, William Dare, and Abner Power, the other villains of the tale.

Although Du Maurier complained to Hardy about the number of figures in the scenes suitable for illustration, and lamented the absence of dramatic incidents in Part II of the instalments, the facts of the matter are that when an instalment of the story did have a dramatic incident, Du Maurier chose a non-dramatic, static situation for his illustration. [Jackson 125]

Image scan, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Created 11 May 2001

Last modified 31 December 2019