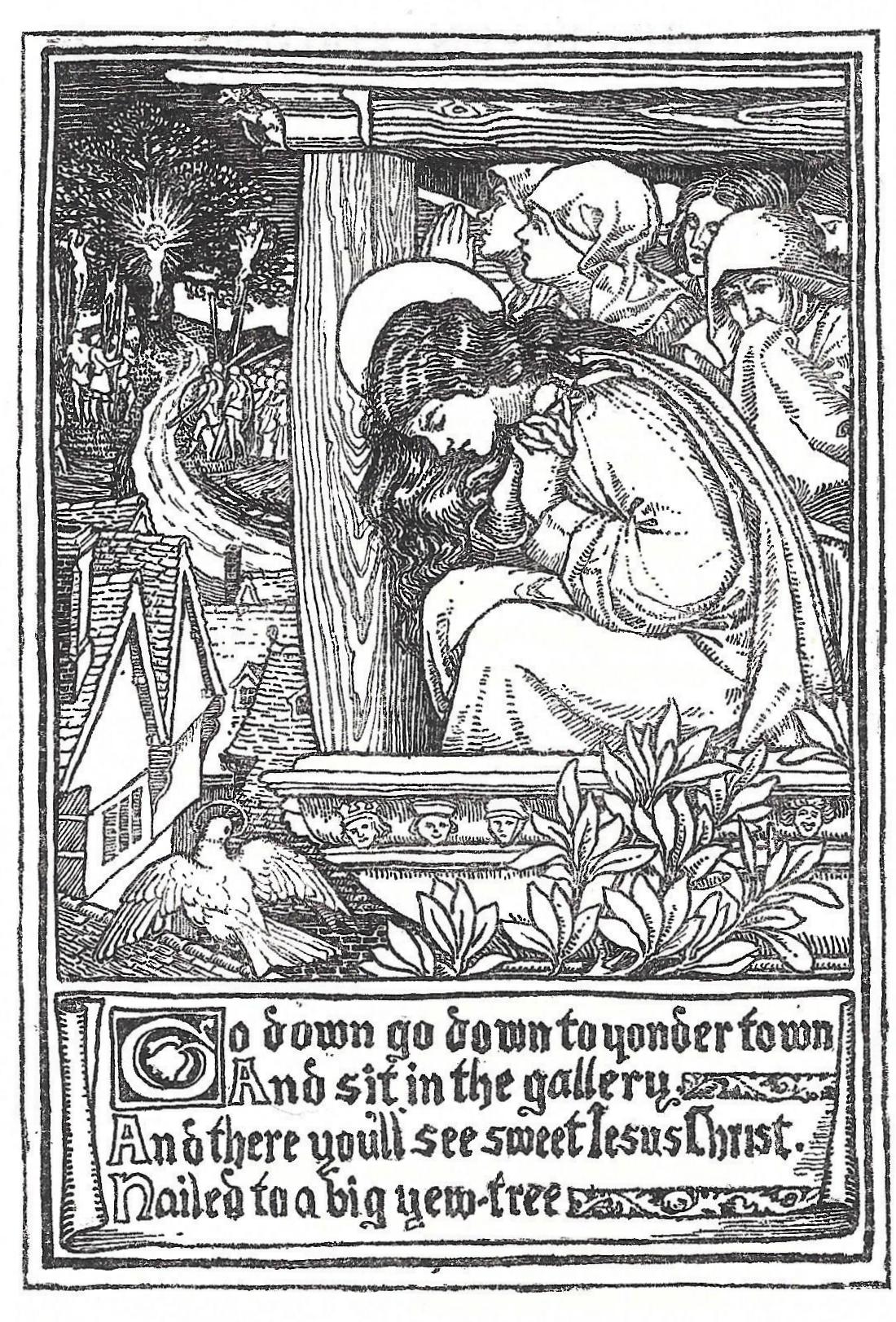

Frederick Mason’s published work combines the figurative devices of Pre-Raphaelitism and the decorative motifs of Morris. Inspired by his teacher Arthur Gaskin, Mason’s illustrations encapsulate this type of synthesis, breathing new life into the conventions of earlier design. His deployment of Pre-Raphaelite imagery is exemplified by his single illustration for Gaskin’s Book of Pictured Carols (1893), The Seven Virgins. The engraving illustrates the scene of the virgins watching Christ’s crucifixion:

Go down, go down to yonder town

And sit in the gallery

And there you’ll see sweet Jesus Christ

Nailed to a big yew tree. [69]

Left: Mason’s The Seven Virgins. Right two: Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s The Palace of Art from the Moxon Tennyson and the title-page for his sister’s Goblin Market. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Mason matches the medieval rhyme with a self-consciously archaic image in the manner of Rossetti. The prime figure, wracked by grief, is closely modelled on the older artist’s drawing of Jane Morris, complete with the distinctive facial features, mobile hands and extravagant dark hair that can be seen, for example, in Rossetti’s Prosperpine (1874, Tate Britain) and in the pictorial title-page for Christina Rossetti’s The Prince’s Progress (1866). The organization of space is likewise Rossettian in the style of his illustrations for the ‘Moxon Tennyson’: the main character is placed in the extreme foreground, and is seemingly too large for the space available, while the background is shown at an extreme distance, in minute detail. Produced under the spell of the Moxon illustrations, Mason’s design is closely linked to the over-large figures, compressed space and Lilliputian detail in Rossetti’s picturing of St Cecilia, Mariana in the South and The Lady of Shalott.

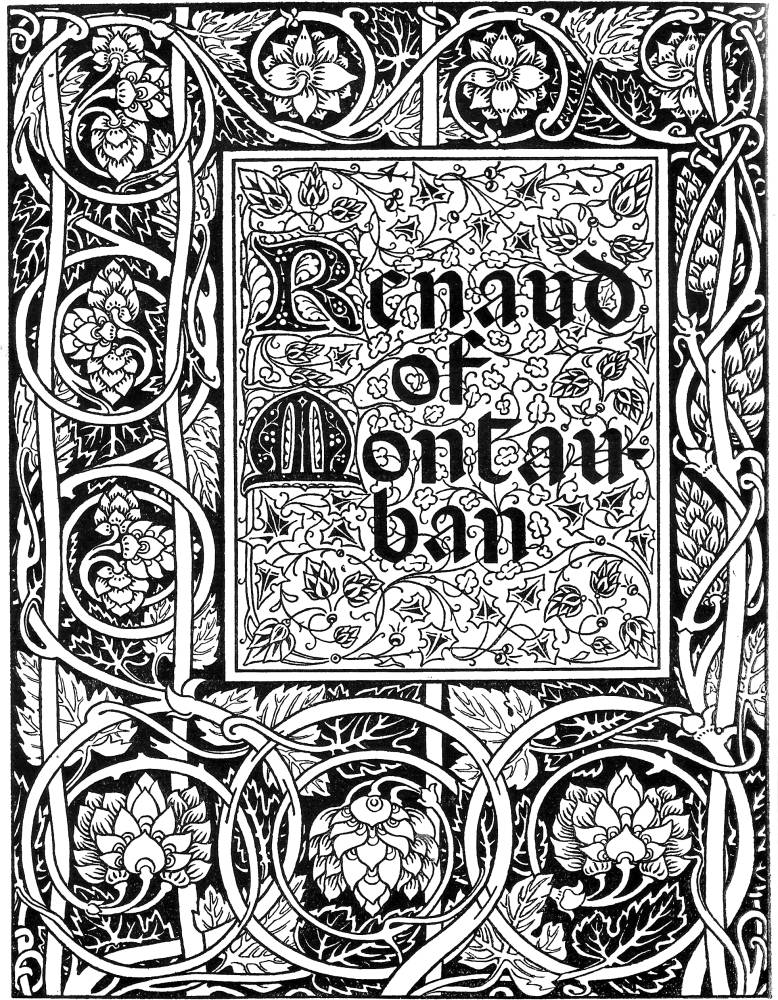

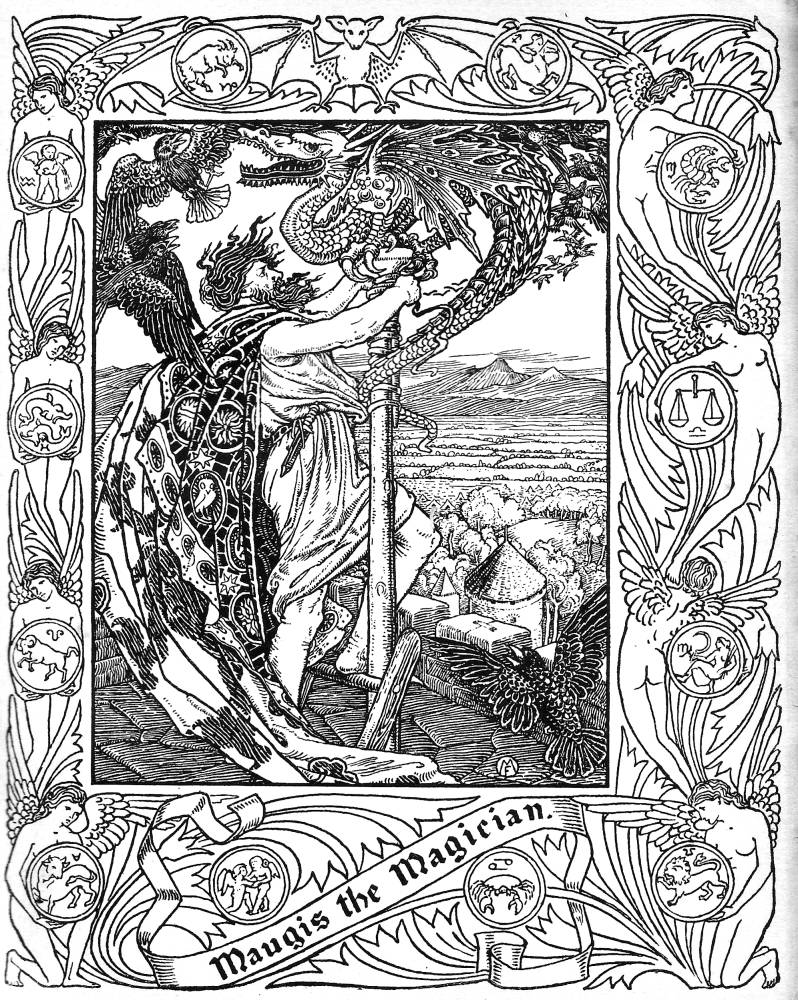

Left: Title-page for Renaud of Montauban. Middle: Maugis the Magician. Right: Selwyn’s Image’s brambles on the The Century Guild Hobby Horse. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Drawing on these examples, Mason’s design is an elegant homage which still has currency and manages to convey personal feeling. Using Rossetti’s style as a pre-existing language, Mason maintains the psychological focus that underpins neo-medieval Pre-Raphaelitism. Indeed, the chief characteristic of his work is its concentrated intensity. In his visualization of Renaud of Montauban he focuses the fast-moving narrative by concentrating on key moments of heightened feeling. In Renaud helps to build the cathedral, for example, he amplifies the scene’s emotional content by emphasising the sheer difficulty of the character’s toil as he works within a limited space. The ‘other labourers’ were are told, had ‘great envy’ for his efforts, and Mason conveys the depth of his spiritual commitment by showing the hero in a tense pose as he struggles with a block of stone. Positioned against a geometrical background of squared masonry and the everyday accoutrements of the masons’ yard, Renaud’s physical efforts are the material sign of his state of mind as he works ‘for the love of God’ (275).

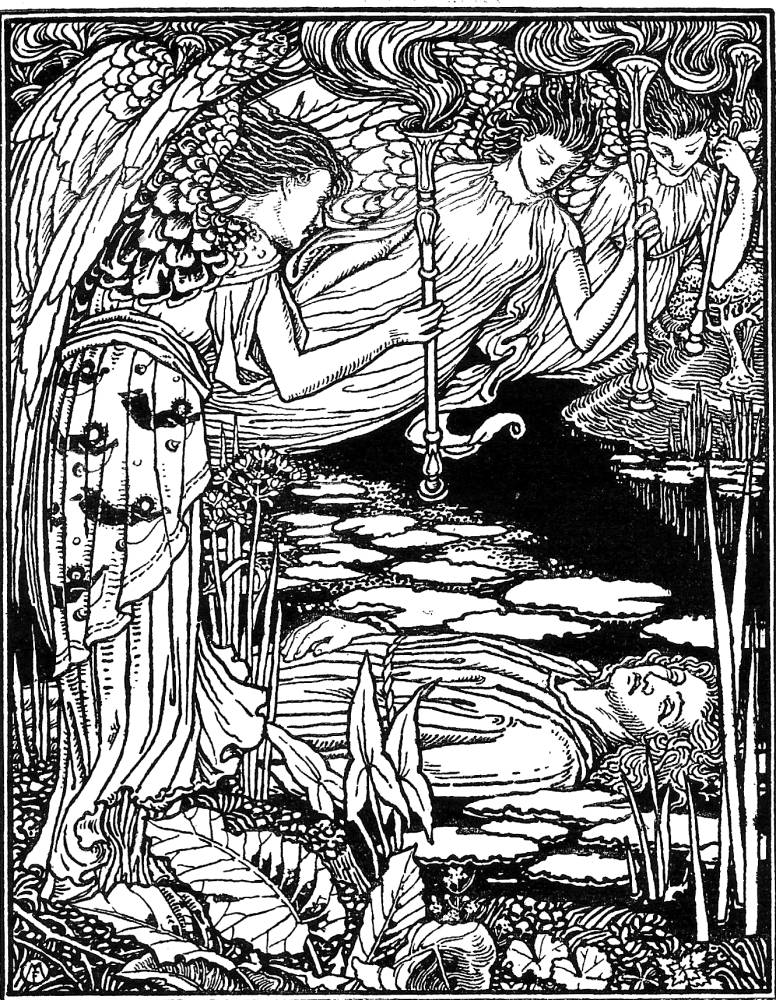

Angels Holding Torches are Seen with Renaud.

Mason also represents the psychological in Angels holding torches are seen with Renaud. The text specifies that Renaud’s body is cast into the Rhine and is borne up by the fishes, with a ‘great light’ (279) appearing around him. In the illustration, however, the artist ignores the detail of the piscine support and adds the figures of angels, missing from the text, to explain the illumination. The aim, once again, is one of intensification: the medieval text specifies the characters’ responses, but Mason represents the sense of loss in the intimate arrangement of the angels, who encircle the dead hero and look tenderly at his face.

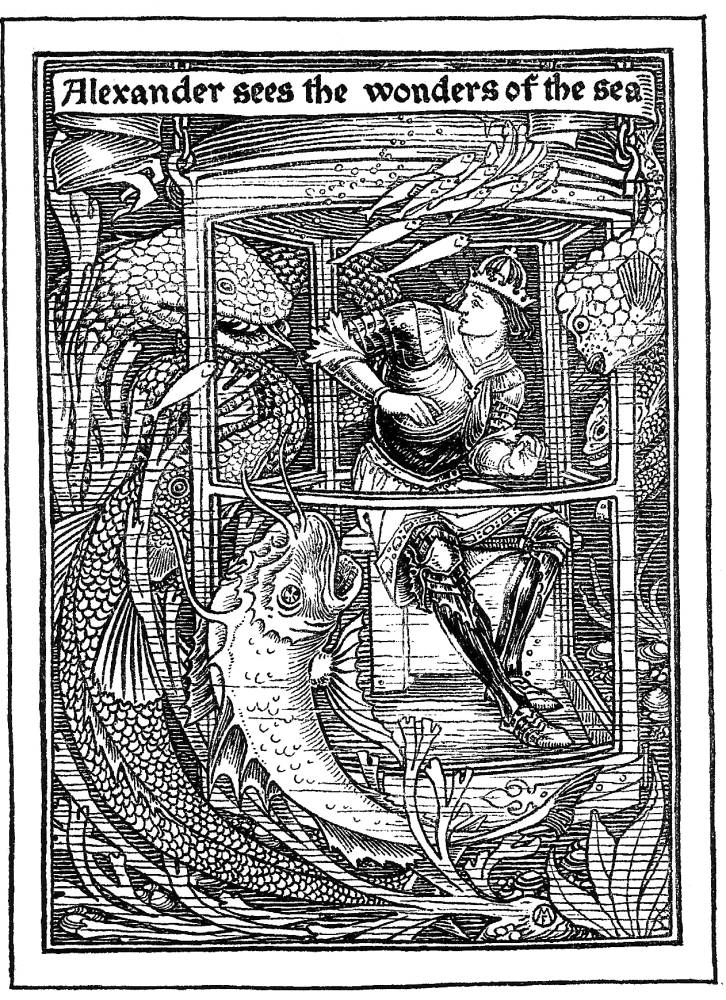

Alexander sees the Wonders of the Sea

The effect is hallucinatory, drawing the reader/viewer into a moment of dream-like perception, and Mason’s designs often proceed well beyond the limits of their texts to suggest a mental landscape. In The Story of Alexander he uses a number of strategies to suggest an archaic, otherworldly innerness, ranging from a curiosity-shop particularization to the imagining of the downright weird. In Anectanabus telleth the Queen’s fate he foregrounds the seer’s paraphanelia, focusing on the box and dice while placing them in an overcrowded room where the costumes and carvings are cloyingly intense, challenging the eye to see everything, foreground, middle and far distance, in the manner of Pre-Raphaelite over-specification which pretends to be ‘real’ but is far beyond reality. Strange exaggeration is also used in Alexander sees the wonders of the sea. The text evokes the encounter, when, sitting in a ‘vessel of glass’ the hero is immersed in a world where he sees

fish whose figures he had never dreamed of, with forms diverse and horrible, and creeping things and four-footed things crawling on the sea bottom … and great monsters came sailing up to the side of the cage and looked in … and other sights he saw such that would never tell to any man till the day of his death, for they were so horrible that tongue could not tell … [202]

The key-note is horrified wonder, and Mason amplifies the sense of the ‘forms diverse and horrible’ by giving them an exaggerated, scaly physicality, seemingly more reptile than fish-like and suggestive of the undulating sea-monsters so often reported in the earlier part of the nineteenth century. Once again, space is important and Mason accentuates Alexander’s sense of fearfulness, literally in the creatures’ mouths, by squeezing the monsters into another impossibly constricted scene.

Mason’s illustrations are figured, in short, as thoughtful, evocative readings of their texts. Drawing on Pre-Raphaelite imagery, his drawing have a rough-edged intensity which is partly the result of his formal inventiveness, partly their imaginative use of an existing lexicon, and partly the result of the bold engraving on wood, which does not resemble the smooth, painterly effects of engravers such as the Dalziels, but has an almost primitive directness; no engraver is identified in any of Mason’s books, but the assumption must be that he did it himself, a practice adopted by the other members of the Birmingham School in Gaskin’s Book of Pictured Carols. All of his books are printed on coarse paper with large print, and taken with the illustrations the publications evoke the incunabula in which the stories originally appeared.

Related material

- Frederick Godwin Mason (homepage)

- Fred Mason’s Training and Illustrations

- Fred Mason, William Morris, and Decorative Features of Mason’s Books

Bibliography: Archival Material

Ancestry.co.uk.

Material in Minutes Books and slide collection of the Art and Design Archive, City University, Birmingham, UK.

Bibliography: Primary Material

A Book of Pictured Carols. London: George Allen, 1893.

The Century Guild Hobby Horse (1886–92).

Field, Michael [Katherine Harris Bradley & Edith Emma Cooper]. The Tragic Mary. London: George Bell, 1890.

The Quarto.Birmingham: Cornish Brothers, 1894–6.

Steele, Robert (translator). Huon of Bordeaux. London: George Allen, 1895.

Steele, Robert (translator). Renaud of Montauban. London: George Allen, 1897.

Steele, Robert (translator). The Story of Alexander. London: David Nutt, 1894.

Wilde, Oscar. Poems. London: Elkin Matthews & John Lane, 1892.

Bibliography: Secondary Material

‘Birmingham Municipal School of Art.’ Birmingham Daily Post (26 July 1892): 5.

Haslam, Malcolm. Arts and Crafts Book Covers. Shepton Beauchamp: Richard Dennis, 2012.

Morris, William. An Address by William Norris at the Distribution of Prizes to Students of the Birmingham Municipal School of Art. London: Longmans, 1898.

Valance, Aymer. ‘A Provincial School of Art.’ Art Journal (1892): 344–8.

Created 11 September 2019