The Late Mr. Matt. Morgan, The Graphic, 14 June 1890: 663 [based on carte-de-visite by Napoleon Sarony].

Matthew Somerville Morgan (1837-1890) was born into a theatrical family in working-class Lambeth on April 27, 1837. His father, Matthew, was an actor and a music teacher, and his mother, Mary Somerville, was an actress and a singer. His paternal aunt had married the painter John Lucas (1807-1874), making Morgan a cousin to the author John Templeton Lucas (1836-1880), the water-colourist William Lucas (1840-1895), and the art publisher Arthur Lucas (b.1842). He was also distantly related to the Royal Academician John Seymour Lucas (1849-1923).

Morgan was ‘cradled in the theatre’, and exhibited an artistic talent from an early age (he may even have decorated the scene-painters’ room of one theatre), and at age 16, gained an apprenticeship with the great masters of scene-painting Thomas Grieve (1799-1882) and William Telbin the Elder (1815-1873). Morgan was therefore an early inductee into one of the theatrical revolutions of his day, as new standards of lavish scene paintings, together with improved lighting, remarkable new standards of costuming, and an effusion of new acting and writing talent re-shaped the Victorian stage. Eventually working with William Roxley Beverley (1814-1889), Morgan honed his talents and was making a name for himself with the painted scenes for ‘Arthur Sketchley’s New Entertainment’ at the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly (1864), imagining the journey from London to Paris.

Matt Morgan with Harvey Orrin Smith, by Horace Harral, an albumen print on a card mount, of 1863, 6 3/4 in. x 6 1/8 in., © National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG x21409), given by Jane Souter Hipkins in 1930.

Morgan was sufficiently well-off by the early 1860s to have married (on January 19, 1860) and started a family. His wife, Caroline Orrin Smith, was the daughter of the engraver John Orrin Smith, who had taught John Leech to draw on the woodblock, was a business partner to William James Linton (husband of Eliza Lynn Linton), and had himself been taught by the great engraver William Harvey (1796-1866). His circles were thus not only theatrical, but also encompassed the world of publishing and illustration, which became his parallel career. An offshoot of both – the brief period in 1862-3 when he owned a gallery in Berners Street, and painted large ‘society’ canvases – was significant in building his social networks (Whistler exhibited there; as did Millais, Frith, and John Phillip; with the likes of Leighton, Prinsep, and also many Punch artists in regular attendance).

Early work for the Illustrated Times, and its more successful rival, the Illustrated London News, took Morgan to southern France and northern Italy, following the outbreak of the war between Napoleon III and Franz Joseph of Austria (1859). He drew scenes of French soldiers crossing rivers, and carousing at farewell concerts, before returning to continue sketching at home (cadets at Portsmouth, and Derby Day). He then joined Fun from 1861 – the rival to Punch founded by Henry J. Byron the previous year – joining the likes of W. S. Gilbert, Francis C. Burnand, E. L. Blanchard, Tom Hood the Younger, and Tom Robertson, on a staff that was heavily involved in the theatre.

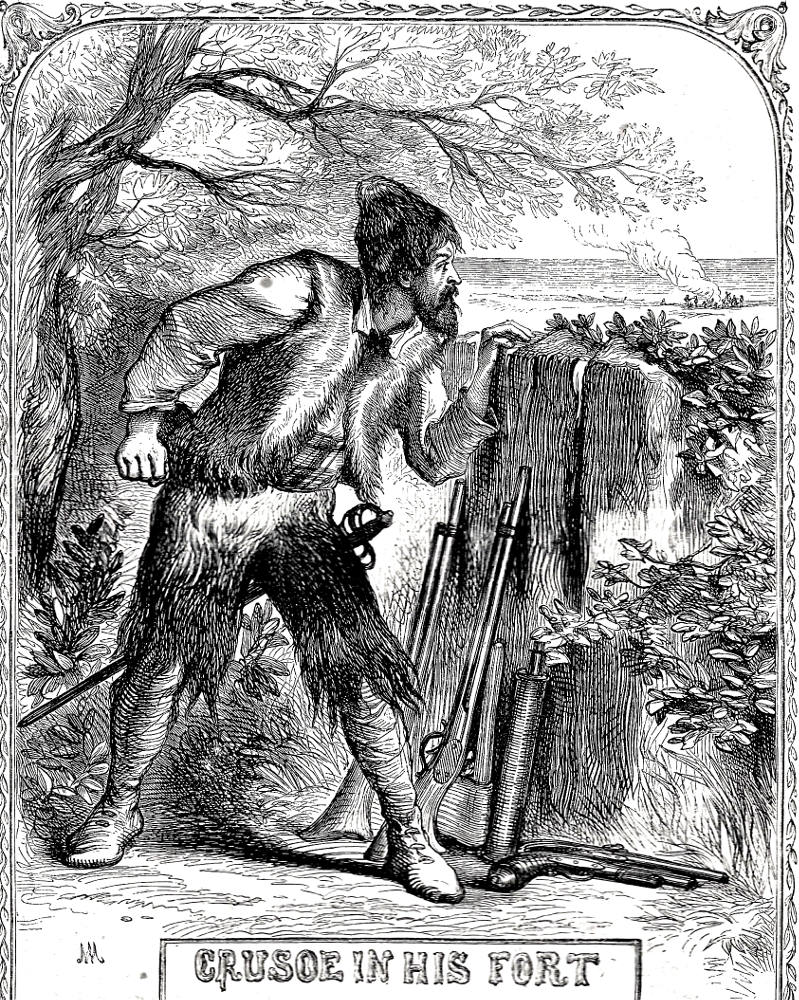

Crusoe in His Fort, one of Morgan's illustrations for the Cassell, Petter, and Galpin ed. of Robinson Crusoe (1863-64), p. 121).

Between 1861 and 1864, Morgan drew rather uneven cartoons on Fun, admitting later to tracing John Tenniel’s depictions of important figures. His main concerns were the unfolding American Civil War, demonising Napoleon III, and chronicling events in Central Europe, as well as the domestic politics of Lord Palmerston’s second government (of which Fun was a die-hard supporter), and regular attacks on the Tory opposition of Lord Derby and Benjamin Disraeli. By 1864, he carried over his much-improved talents to two short-lived comic papers The Arrow (1864) and The Comic News (1863-1865), founded by playwrights Henry S. Leigh and Henry J. Byron, respectively. The latter paper, having briefly been renamed The Bubble, promptly burst.

There was a two-year hiatus in Morgan’s cartooning career, during which he concentrated on his theatrical work. Christmas pantomimes were Morgan’s metier, and especially the lavish, balletic ‘Transformation Scenes’ that characterised them. Successive seasons saw growing success with E. L. Blanchard’s Cinderella (1864-1865), Gilbert Arthur à Beckett’s Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves (1866-1867) and Babes in the Wood (1867-1868), Henry Byron’s Robinson Crusoe (1868-1869) and The Yellow Dwarf (1869-1870). These were staged at Covent Garden, and drew considerable praise, as did the production of Romeo e Guilieta (1867) by the Royal Italian Opera.

Firm friends from the pantomimes, in 1867, Morgan began collaborating with Gilbert Arthur à Beckett on a new satirical paper The Tomahawk, which was designed to rival Punch (and be cheaper at 2d to Punch’s 3d). The high moral tone of the paper reflected the aspirational, middle-class pretension of Morgan as much as the Roman Catholic conservatism of à Beckett, but this was a conservatism as much aimed at the stuffiness of the establishment as anything else. As might be expected, given the theatrical experience of the editor and cartoonist, the Lord Chamberlain was attacked for his attempts to censor the costumes and scenery of the theatre (especially efforts at forcing ballet-girls to wear more clothing), but it was the assault on Queen Victoria that made Tomahawk a sensation.

Left to right: (a) Morgan’s signature from his Illustrated London News work (1859). (b) Morgan’s monogram from his signed Fun (1861-1864), Arrow (1864), Comic News (1863-1865), Judy (1867), and Tomahawk (1867) work. (c) The ‘tomahawk’ signature of Morgan’s early work on the eponymous magazine (1867). (d) Morgan’s self-confident signature of 1867-1870, and his work on Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (post-1871).

‘Where is Britannia?’ (8 June 1867, p.55) imagined the throne vacant; while ‘A Brown Study’ (10 August 1867, pp.151-152) went further, and showed John Brown leaning on the throne and playing with the British Lion. The cartoons apparently lifted sales of the Tomahawk to 50,000 (approaching Punch’s own), but for the moment, the cartoonist’s identity was concealed: Morgan signed them with a small tomahawk, not with his own initials or name. There was outrage in the press, and around the Punch table, as well as in other cartoons. In the arch-Conservative Judy, ‘The Widow’s Home’ and ‘Slandered by Traitors’ attacked the Tomahawk and the other papers for their disloyalty to the Queen; the irony being that both cartoons were drawn by Judy’s chief cartoonist of the time: Matthew Somerville Morgan. As Tomahawk grew in stature, Morgan felt able to leave Judy, and – from late August 1867 – begin to append his own initials ‘MM’, or full signature ‘Matt Morgan’ to his Tomahawk cartoons.

While Tomahawk flourished for a time, Morgan seems to have aspired to a lifestyle beyond his station. He moved his family from Islington to Bloomsbury, joined a Volunteer regiment (along with à Beckett), and took up hunting and frequenting the races. His cartoons were increasingly on the grand scale: no only double-pages, but also printed in colour, and highly theatrical. Domestic concerns and the foreign politics of the late 1860s gave room to criticise the lifestyle of the Prince of Wales, express great fears at the revolution in Spain, and chronicle the brief rise of Disraeli to the top of the ‘greasy pole’ before Gladstone’s first premiership. His last cartoons were evocative imaginings of the Rhine frontiers and the beginnings of the Franco-Prussian War, before Tomahawk folded in murky financial crisis. Morgan himself had been chased by creditors for some time (he was arrested in 1869), and seems to have fled to the Continent in 1870, sending sketches back to à Beckett of gypsy dancers in Spain. His wife, Caroline, disappears from the record around this time, and by the time Morgan himself arrived in the United States, she had been replaced by Susan Elizabeth Slade (1850-1903), a beautiful young actress from the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden.

Morgan was lured across the Atlantic by Frank Leslie (1821-1880), whose Illustrated Newspaper (founded 1855) was the central pivot in a growing periodicals empire. Apparently for a salary of $10,000 a year, and with the story that his cartoons of Queen Victoria had led to his exile from Britain, Morgan soon found a place in New York’s journalistic and theatrical circles. During the presidential election of 1872, he served as the foil to Thomas Nast (Harper’s Weekly), supporting the Democrat, Horace Greeley, against the eventual easy victor, General Ulysses S. Grant. Early involvement in a divorce case in 1873 (the chief beneficiary of which was Leslie, who then married the complainant), was followed by pushing the boundaries of propriety with a revival of The Black Crook (1873) and 1875’s ‘Mr Matt Morgan’s Magnificent Classical Tableaux’ (tableaux vivants of near-naked actresses).

Morgan’s American career was as varied as his British one, with his New York period followed by tours to Pittsburgh and Louisville, and then a more permanent move to Cincinnati (1879), where he founded the Strobridge Lithographing Company. Also founding an art school and a pottery company, he supplemented his income by continuing to draw cartoons (even sending some back to Britain for the St. Stephen’s Review), and painting enormous canvases, including panoramas of Civil War battle scenes (1886-1887), and on religious themes (Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem, 1888). The new American arena extravaganzas were a perfect forum for Morgan’s scene-painting, and he contributed the scenes for James Steel MacKaye’s The Drama of Civilization, (1886), and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Back in New York City, Morgan was completing scenes for a new series of ballets at Madison Square Garden when he was felled by a heart attack, dying at home on Lexington Avenue and Seventy-First Street, on 2 June 1890. He was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery.

Morgan’s family – including his second wife (Susan Elizabeth Slade and he had married on September 24, 1886, just across the border in London, Ontario), and seven children by her – were shocked by his sudden death. To secure their finances, Mrs Morgan eventually acquired all rights to the name ‘Matt Morgan’, possibly arising out of conflict with Matt’s son Fred from his first marriage (who often signed his work as ‘Matt Morgan Junior’). Morgan was sufficiently well-known to merit obituaries on both sides of the Atlantic, and was remembered fondly in memoirs published by George Du Maurier, Arthur William à Beckett, and others from his London days).

Bibliography

Bunker, Gary L., ‘The Comic News, Lincoln, and the Civil War’, xJournal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 17, no.1 (Winter 1996): 53-87.

Kemnitz, Thomas Milton, ‘Matt Morgan of “Tomahawk” and English Cartooning, 1867-1870’, Victorian Studies XIX, no.1, (September 1975): 5-34.

Kent, Christopher, ‘Spectacular History as an Ocular Discipline’, Wide Angle 18, no.3 (July 1996): 1-21.

_____. ‘The Angry Young Gentlemen of Tomahawk’, in Barbara Garlick & Margaret Harris (eds), Victorian Journalism: Exotic and Domestic. Essays in Honour of P. D. Edwards. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 1998. 75-94.

_____. ‘War Cartooned/Cartoon War: Matt Morgan and the American Civil War in Fun and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Victorian Periodicals Review 36, no.2 (Summer, 2003). 153-181.

_____. ‘Matt Morgan and Transatlantic Illustrated Journalism, 1850-90’, in Joel H. Wiener & Mark Hampton (eds). Anglo-American Media Interactions, 1850-2000. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. 69-92.

Scully, Richard. ‘The Epitheatrical Cartoonist: Matthew Somerville Morgan and the World of Theatre, Art and Journalism in Victorian London’, Journal of Victorian Culture 16, no.3 (December 2011): 363-384.

_____. ‘Sex, Art and the Victorian Cartoonist: Matthew Somerville Morgan in Victorian Britain and America’. International Journal of Comic Art. 13, no.1 (Spring 2011): 291-325.

_____. Eminent Victorian Cartoonists – Volume II: The Rivals of ‘Mr Punch’. London: Political Cartoon Society, 2018 (esp. pp.8-50).

Created 21 February 2022