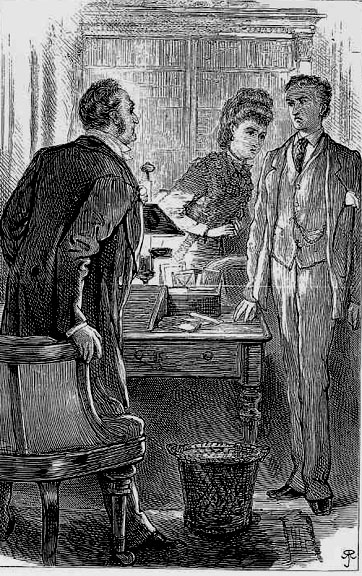

The Vicar is Indignant

James Abbott Pasquier

November 1872

Illustration for Thomas Hardy's A Pair of Blue Eyes, Tinsley's Magazine, chapters 9-11, XI, 82

11.4 cm wide and approximately 17.6 cm high

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> James Abbott Pasquier—> Next]

The Vicar is Indignant

James Abbott Pasquier

November 1872

Illustration for Thomas Hardy's A Pair of Blue Eyes, Tinsley's Magazine, chapters 9-11, XI, 82

11.4 cm wide and approximately 17.6 cm high

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Apparently Thomas Hardy's first father-in-law, retired solicitor John Attersoll Gifford, was not overjoyed at the prospect of welcoming the thirty-two-year-old architect with literary pretensions into his family, so that the scene in Rev. Swancourt's study may be an understated recollection of the novelist's making his proposal for Emma's hand to Mr. Gifford. As Michael Millgate remarksin Thomas Hardy: His Career as a Novelist (1971), it is not "surprising that Hardy, writing his first serial with inadequate preparation and under constant pressure from the printer, should resort to fictional exploitation of his own experiences" (67). In writing both the anonymously published Desperate Remedies (25 March 1871) and Under the Greenwood Tree (June 1872), to which volume works each month's bannerhead of A Pair of Blue Eyes in Tinsley's Magazine alludes, Hardy did not have to contend with the stresses inherent in serial composition. It is likely that in writing A Pair of Blue Eyes he was also mining his first (unpublished) novel, The Poor Man and the Lady (1867-9), in which class-consciousness likewise separates the lovers. For the first time in the publication of a novel, Hardy is credited with authorship. That both Henry Knight and Elfride Swancourt are proto-novelists once again reflects the quasi-autobiographical nature of this third published Hardy novel.

No sooner has Elfride resolved the mystery of the woman on the shade than another impediment to her loving Stephen presents itself: her father's refusal based on Stephen's declaration that his father is no Caxbury aristocratic scion but the mason on Lord Luxellian's estate. In the November 1872 illustration, when suddenly made aware of Stephen Smith's plebeian background, Reverend Swancourt (whose appreciation of aristocratic birth Hardy early established by the parson's referring in Chapter III to the Landed Gentry for the origins of "Stephen Fitzmaurice Smith of Caxbury") rebuffs Stephen's offer of marriage. This is the conventional proposal scene of Victorian romance in which the young suitor asks the permission of the stern Pater Familias to marry his only child -- the situation being a far cry from the many-daughtered Reverend Mr. Bennet in Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice (1813). Elfride's hairdo and clothing suggest the formality of the scene, and her downcast look betokens Stephen's failure. Whereas Stephen and Rev. Swancourt look directly at one another, the disappointed architect lightly touching the desk but the indignant Anglican clergyman clutching the arm of his chair, Elfride looks off-stage left, signalling her intention to quit the room. The parson's frock-coat and Stephen's modern business suit convey their relative ages as well as their professions. The chapter title, "Her Father Did Fume" and the expressions on the characters' faces and their relative juxtapositions telegraph to the reader the outcome of Stephen's proposal. Elfride, although occupying the space between the two men, is moving towards Stephen and away from her father, foreshadowing the couple's elopement, perhaps. Although Pasquier does not depict the vicar's straw hat, it must be just off the left of the frame because, immediately after expressing his determination to conduct no "private business" with the London architect's man, he puts it on and strides through the drawing-room (stage-right, behind Stephen) and out onto the verandah. The empty wastepaper basket may be merely a realistic detail, or a symbol of the futility of Stephen's actions. Like Elfride, the wastepaper basket in the foreground separates the contending males, its two handles suggesting the tug-of-war of emotions and loyalties.

The picture's proportions are a little off, for in attempting to show Elfride as equal to Stephen in terms of importance in this scene Pasquier has neglected to show her skirts and feet on the other side of the desk. The basket, writing materials, large desk, and book-lined shelves in the rear are all consonant with the setting, but they also serve to hem the young couple in: as they seem penned in by material objects connected with her father's profession, in their attempt to marry they are restricted by the conventions of the materialistic class system. Stephen appears to be wearing the same clothing that he had on when he and Elfride visited the cliffs in the second plate, providing continuity between the two illustrations. Although Hardy describes Stephen as having a moustache in Ch. 2, none is evident in this third plate. Although Stephen's tweed waistcoat and suit certainly suggest "the London professional man," and his rounded cheeks his relative youth, Hardy describes only the last of these elements of the character.

Created 21 June 2003

Last modified 4 January 2020