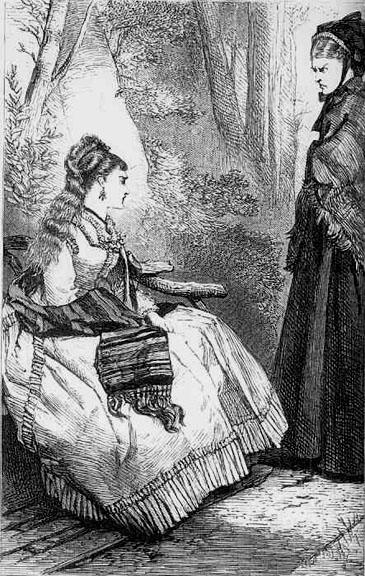

Mrs. Jethway's Accusation

James Abbott Pasquier

April 1873

11.4 and approximately 17.6 cm high

Illustration for Thomas Hardy's A Pair of Blue Eyes in Tinsley's Magazine, chapters 26-28, XII, 272

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> James Abbott Pasquier—> Next]

Mrs. Jethway's Accusation

James Abbott Pasquier

April 1873

11.4 and approximately 17.6 cm high

Illustration for Thomas Hardy's A Pair of Blue Eyes in Tinsley's Magazine, chapters 26-28, XII, 272

But Mrs. Jethway, silently apostrophising the house, with actions which seemed dictated by a half-overturned reason, had discerned the girl, and immediately came up and stood in front of her. (Ch. XXVIII, the last chapter in the April 1873 instalment)

Although the setting is the grounds of Elfride's step-mother's mansion adjacent to the vicarage of her father, the sketched-in trees and closely juxtaposed figures of the two women impart a distinctly theatrical quality to Pasquier's eighth illustration for Thomas Hardy's first serialised novel. An ebony column blending into the right-hand margin, the Widow Jethway is a reification of Elfride's ever-active guilty conscience, so that, although the older woman glares at her, Elfride in the plate seems powerless to make direct eye-contact with her as she nervously grips her shawl. Appropriately, the heroine's coiffure is a combination of free-flowing locks (suggestive of her determination to love where she will, maugre the opinions and proprieties of society in general, and the aggrieved mother of her supposed "first love" in particular) and elegantly styled locks and bangs which bespeak not merely the fact that she has a maid and the leisure to indulge in such ornamentation but also her desire to attract the opposite sex. Her hair, indeed, is her chief source of vanity, and the thought that it will soon thin seems to her an indication of her mortality. Pasquier has dressed her in a fashionable gown more suited to the drawing-room than a walk through the grounds of the estate. However, the abundant flounces, seen in the other dress in which she is depicted in earlier plates, are indicative of her love of fashionable clothing and jewelry appropriate to a scion of the aristocracy (she is, we have learned since the March instalment, a cousin on her mother's side of the present Lord Luxellian).

Confronted about her fickleness by the mother of the young farmer who supposedly died of unrequited love rather than consumption, Elfride in Pasquier's April plate appears somewhat older than her twenty years, an age which Hardy underscores in this instalment by having Elfride substitute it for the subject of her appointed " confession " to Knight on the morning preceding this unwanted interview with the late Felix Jethway's aggrieved parent. Throughout the April number, Elfride fears that circumstances will bring to Knight's attention her previous romantic interlude with Stephen Smith. By accident, she and her new beau encounter the young architect at the Luxellian vault, but, given the opportunity to reproach her for having jilted him, Stephen generously pretends not to know her. Although Hardy has hinted many times that Knight will be quite upset if he learns that his beloved has had other admirers and romantic interlocutors prior to him, the reader is kept in doubt as to precisely what Knight's response to Elfride's "secret" will be. At the very close of the April number, she lets slip a remark about losing an earring that threatens to reveal that past relationship she has so assiduously avoided confessing to Knight, so that the serial "curtain " precipitates the reader ahead to the next monthly instalment.

The immediate textual context of the April plate is that, since Knight has offered to take her for a tranquil walk by the river, she has asked that he wait at the bench while she retrieves an appropriate hat from the house. The smitten Knight, however, has gallantly offered to let her rest on the bench while he procures the hat for her. (One speculates as to why she has not already been wearing one, and how Knight will know which hat to select, but, of course, her father's recent marriage means that she has numerous servants to assist Knight.) Detecting the approaching widow before Mrs. Jethway has seen her sitting amidst the shrubberies, Elfride hopes to avoid a disturbing interview with the "unpleasant woman." Ironically, the widow begins by accusing Elfride of intruding upon her solitude: "Why did you disturb me? Mustn't I trespass here?" The word "trespass" implies the speaker's resentment in the disparity in their social positions since her father's recent marriage has elevated her into the land-owning class. Mrs. Jethway then accuses the hapless girl of having killed her son by proving false after agreeing to be his sweetheart. Elfride's rejoinder certainly indicates that the grieving mother has vastly overstated the case, and that Elfride's showing modest marks of favour to the boy (such as permitting him to hold her pony as she dismounted) was hardly tantamount to accepting an offer of marriage. Not only the widow's footsteps but her thoughts, implies Hardy, are "irregular."

Although Elfride's assumption that a medical rather than a nervous disorder carried off Felix Jethway, her intense guilt at her treatment of Stephen and her keeping Knight in ignorance of the prior attachment prevent her from maintaining her indignation at this ridiculous accusation. But Mrs. Jethway knows her weakness, and threatens to expose her "would-be runaway marriage" to the unknowing "new man" in her life. With Knight expected any moment, the reader anticipates that Elfride will be rudely unmasked as a mantrap. However, surprisingly (or not, given the serial novel's need to generate suspense from one instalment to the next by maintaining such secrets) the widow elects to grant the fickle girl a temporary reprieve; Mrs. Jethway thus conveniently disappears down the garden path as Knight returns with Elfride's hat. That the plate illustrates a point earlier rather than later in the interview is signaled by the absence of Knight in the background.

Rather, the moment realised must be Elfride's indignant response to the widow's charge: "I defy you as a slanderous woman!" she cries in anguish, her voice nonetheless trembling in her apprehension that Knight may return momentarily. All that Hardy has given Pasquier to work with is Elfride's not wearing a hat, the rusticated bench (which the artist represents as made of boughs), the shrubberies, and the path. Since Mrs. Jethway is a widow and is, moreover, undoubtedly wearing mourning, the illustrator has dressed her in weeds and a severe bonnet with a black ribbon tie. Both women, walking out-of-doors, are wearing fashionable Indian shawls (an interesting visual reminder of how Stephen Smith intends to render himself a suitable wooer for a parson's daughter, money being a socially sanctioned substitute for birth). Elfride is clearly the focal character as she occupies so much of the picture and her head is framed by the crossing diagonals of the crossing the light-coloured tree-trunks, both presumably poplars or birches. The forms of the tree-trunks in the background seem to press in on Elfride, underscoring the pressure under which the widow is placing her. The binary opposites of the scene render the construction of the scene effective: the youthful, bare-headed, fashionably coiffed Elfride is shown in profile (perhaps to suggest the secretive aspect of her nature), seated, wearing a light, voluminous, expensive dress; the middle-aged, severely-capped, Spartanly dressed Mrs. Jethway is shown occupying most of the height of the plate, looking down physically as well as morally upon the woman whom she blames for son's death.

canned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Last modified 11 July 2003