"Do you always smoke after you goes to bed, old cock?" inquired Mr. Weller of his land-lord, when they had both retired for the night (See page 308.) by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) on page 321 in the Household Edition (1874) of Dickens's Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, Chapter XLIV, “Treats of divers little Matters which occurred in the Fleet, and of Mr. Winkle's mysterious Behaviour; and shows how the poor Chancery Prisoner obtained his Release at last.” Wood-engraving, 4 ⅜ inches high by 5 ½ inches wide (11.1 cm high by 14.1 cm wide), framed, half-page; descriptive headline: "How the Cobbler was Ruined" (p. 309). [Click on the illustration to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated: Sam encounters a long-term prisoner, a Cobbler

Finding all gentle remonstrance useless, Mr. Pickwick at length yielded a reluctant consent to his taking lodgings by the week, of a bald-headed cobbler, who rented a small slip room in one of the upper galleries. To this humble apartment Mr. Weller moved a mattress and bedding, which he hired of Mr. Roker; and, by the time he lay down upon it at night, was as much at home as if he had been bred in the prison, and his whole family had vegetated therein for three generations.

"Do you always smoke arter you goes to bed, old cock?" inquired Mr. Weller of his landlord, when they had both retired for the night.

"Yes, I does, young bantam," replied the cobbler.

"Will you allow me to in-quire wy you make up your bed under that 'ere deal table?" said Sam.

"Cause I was always used to a four-poster afore I came here, and I find the legs of the table answer just as well," replied the cobbler.

"You're a character, sir," said Sam.

"I haven't got anything of the kind belonging to me," rejoined the cobbler, shaking his head; "and if you want to meet with a good one, I'm afraid you'll find some difficulty in suiting yourself at this register office."

The above short dialogue took place as Mr. Weller lay extended on his mattress at one end of the room, and the cobbler on his, at the other; the apartment being illumined by the light of a rush-candle, and the cobbler's pipe, which was glowing below the table, like a red-hot coal. The conversation, brief as it was, predisposed Mr. Weller strongly in his landlord's favour; and, raising himself on his elbow, he took a more lengthened survey of his appearance than he had yet had either time or inclination to make.

He was a sallow man — all cobblers are; and had a strong bristly beard — all cobblers have. His face was a queer, good- tempered, crooked-featured piece of workmanship, ornamented with a couple of eyes that must have worn a very joyous expression at one time, for they sparkled yet. The man was sixty, by years, and Heaven knows how old by imprisonment, so that his having any look approaching to mirth or contentment, was singular enough. He was a little man, and, being half doubled up as he lay in bed, looked about as long as he ought to have been without his legs. He had a great red pipe in his mouth, and was smoking, and staring at the rush-light, in a state of enviable placidity. [Chapman & Hall Household Edition, Ch. XLIV, “Treats of divers little Matters which occurred in the Fleet, and of Mr. Winkle's mysterious Behaviour; and shows how the poor Chancery Prisoner obtained his Release at last,” pp. 308-309]

Commentary: Phiz's version of "The Chancery Prisoner"

Phiz's American counterpart, Thomas Nast in his 1873 series for Harper and Brothers offers illustrations neither for Chapter XLIII nor for XLIV in his somewhat cartoonish interpretation of The Pickwick Papers, providing instead a woodcut relating to the comic Reverent Stiggins subplot in Chapter XLV. Here, however, in his expanded series for the Household Edition Phiz took this opportunity to create entirely new illustrations for these chapters. Neither illustration has a counterpart in the original serial illustrations for instalments fifteen and sixteen (July-August 1837), and both are among the seventeen entirely new illustrations that Phiz developed for the Household Edition. The expanded program gave Phiz the opportunity to balance the fortunes of Samuel Pickwick and those of Sam Weller, making the latter in essence the novel's co-protagonist.

Neither this nor the previous illustration, "Sam, having been formally introduced . . . . as the offspring of Mr. Weller, of the Belle Savage, was treated with marked distinction", has a counterpart in the original serial illustrations, and both are among the seventeen entirely original illustrations that Phiz developed for the Household Edition, giving him the opportunity to focus on the character and fortunes of Sam Weller, making him in essence the novel's co-protagonist. In fact, in the fifty-seven illustrations in the Chapman and Hall Household Edition, Pickwick appears in just twenty-two, Sam (despite the fact that he doesn't make an appearance in the initial chapters) in twenty-two — the pair together in eight of the woodcuts.

In Chapter XLIV, although Nathaniel Winkle requests Sam's assistance in prosecuting his romantic pursuit of Arabella Allen, Sam is not free to leave the Fleet, where he settles in comfortably, as always making the best of a bad lot (in this case, being incarcerated for a debt he owes his father), as we see in the 1873 illustration and Sam's dialogue with his landlord, an old cobbler who has fallen victim to Doctors' Commons and the Court of Chancery over legal actions brought against him when he became the executor of a relative's estate.

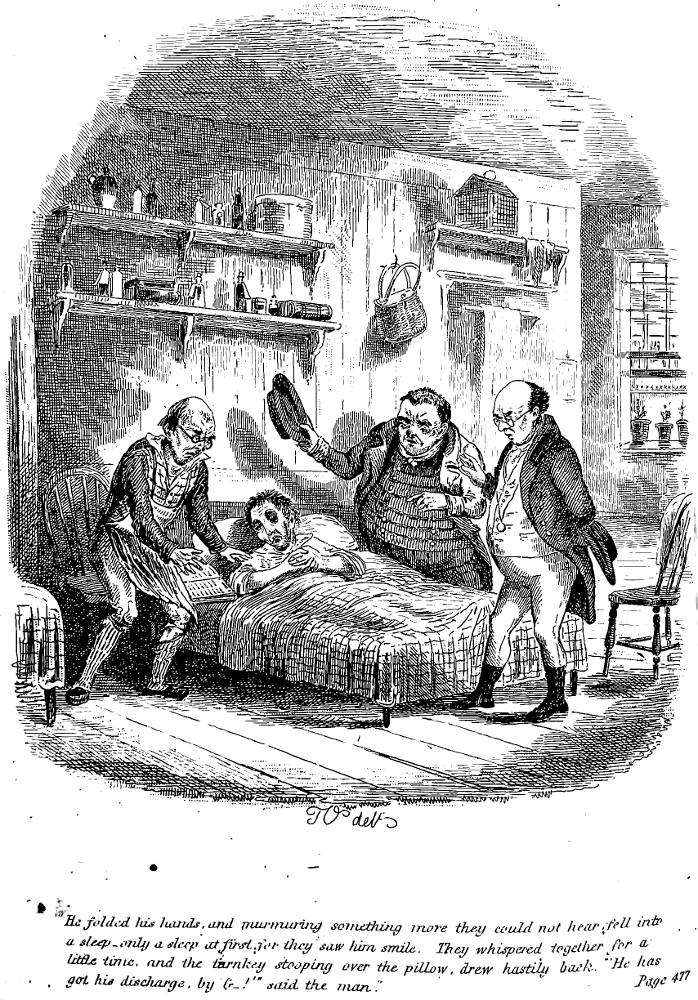

Left: Thomas Onwhyn's "extra" illustration for the original 1836-37 series

is the first visual treatment of the Chancery Prisoner, “He

folded his hands, and murmuring something more they could not hear, fell into a sleep —

only a sleep at first, for they saw him smile.

They whispered together for a little

time, and the turnkey, stooping over the pillow, drew hastily back. He has got his

discharge, by G_.” (15 November 1837).

There follows what amounts to an integrated first-person narrative on the vagaries of the English legal system. The illustration conveys a sense of both characters, the sanguine old cobbler and the equally sanguine Sam Weller, both sleeping on the floor of a spacious furnished apartment. Although the rush light is positioned on the mantelpiece, the room seems much better lit than Dickens describes. Whereas the cobbler's pipe is "glowing below the table, like a red-hot coal" (308) because the room is in near darkness, Phiz communicates the effect through its billowing smoke, somewhat altering the atmosphere of the ensuing dialogue. The old man's attitudes about the injustices of the property-inheritance system and his gradually revealed bitterness are not suggested, so that the illustration does not seem to be referring to anything of substance, whereas the cobbler's tale is Dickens's indictment of a system he knew so well as a legal clerk and then a reporter. Unfortunately, although this illustration conveys an accurate image of the physical particulars of the old cobbler, it presents a "sanitized" image of life in a debtors' prison, suggesting that Phiz (unlike Boz) was unfamiliar with conditions in such places in the 1830s, the misery, the dinginess, the lack of sanitation, and the all-consuming desperation rampant in these deplorable institutions.

Related Material

- The complete list of illustrations by Seymour and Phiz for the original edition

- An introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

- Harry Furniss's illustrations for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Other artists who illustrated this work, 1836-1910

- Robert Seymour (1836)

- Thomas Onwhyn (1837)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1861)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1867)

- Thomas Nast (1873)

- Harry Furniss (1910)

- Clayton J. Clarke's Extra Illustrations for Player's Cigarettes (1910)

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. Formatting by George P. Landow. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File and Checkmark Books, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Robert Seymour, Robert Buss, and Phiz. London: Chapman and Hall, November 1837. With 32 additional illustrations by Thomas Onwhyn (London: E. Grattan, April-November 1837).

_____. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

_____. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. The Household Edition. 22 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1873. Vol. 2.

_____. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. Vol. 5.

_____. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 2.

_____. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. Vol. 1.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. The Household Edition. 16 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1873. Vol. 4.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. Vol. 6.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 2.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens. 2 vols. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. I.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 2. "The Beginnings of 'Phiz': Pickwick, Nickleby, and the Emergence from Caricature." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. Pp. 24-50.

Created 20 April 2012

Last modified 26 April 2024