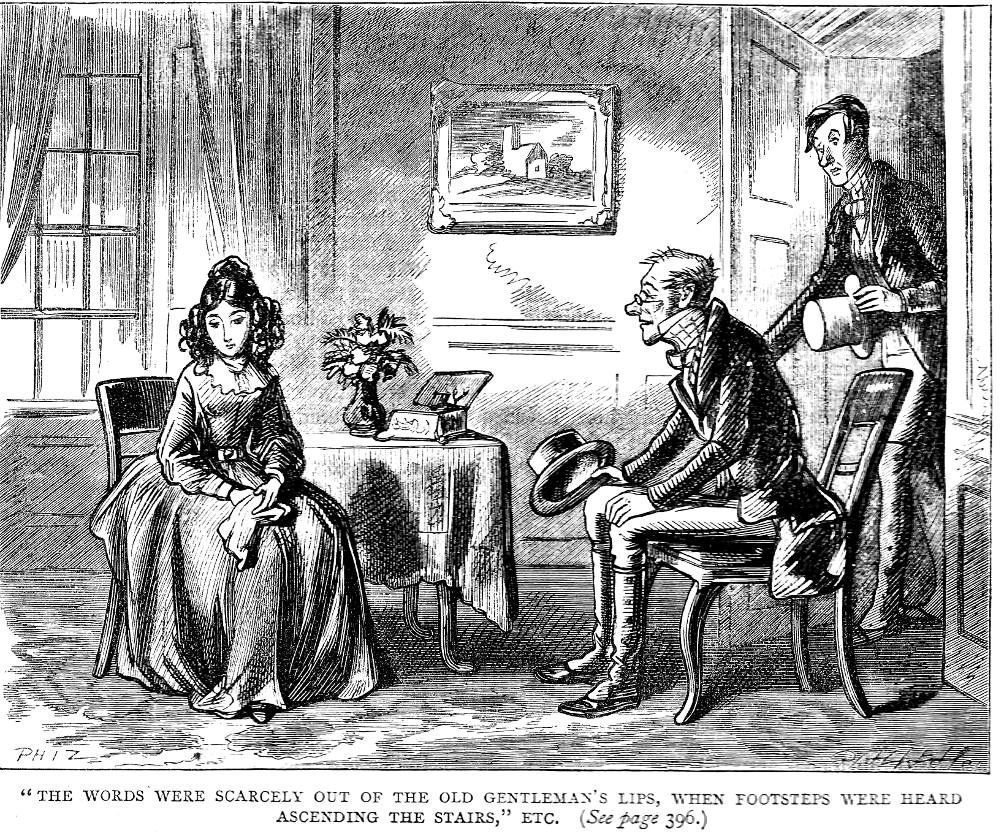

The words were scarcely out of the old gentleman's lips, when footsteps were heard ascending the stairs by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) in the Household Edition (1874) of Dickens's Pickwick Papers, p. 397. Engraved by one of the Dalziels. Chapter LVI, “An important Conference takes place between Mr. Pickwick and Samuel Weller, at which his Parent assists. An old Gentleman in a snuff-coloured suit arrives unexpectedly,” on page 397. The illustration is 11.1 cm high by 14.3 cm wide (4 ¼ by 5 ½ inches), framed. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated: Nathaniel Winkle obtains Parental Approval for his marriage

While this conversation [with the Wellers] was passing in Mr. Pickwick's room, a little old gentleman in a suit of snuff-coloured clothes, followed by a porter carrying a small portmanteau, presented himself below; and, after securing a bed for the night, inquired of the waiter whether one Mrs. Winkle was staying there, to which question the waiter of course responded in the affirmative.

[Upon being admitted to her room, the old gentleman, merely designated as "The Unknown," ascertains that she is Mrs. Winkle and that she expects her husband to return momentarily. Since the elderly visitor seems charmed by Arabella, the reader anticipates that he has travelled by coach all the way from Birmingham to give the young couple his blessing, although he is a little resentful that his son failed to consult him prior to the wedding, or, for that matter, invite him.]

"It was my fault; all my fault, sir," replied poor Arabella, weeping.

"Nonsense," said the old gentleman; "it was not your fault that he fell in love with you, I suppose? Yes, it was, though," said the old gentleman, looking rather slily at Arabella. "It was your fault. He couldn’t help it."

This little compliment, or the little gentleman's odd way of paying it, or his altered manner — so much kinder than it was, at first — or all three together, forced a smile from Arabella in the midst of her tears.

"Where’s your husband?" inquired the old gentleman, abruptly; stopping a smile which was just coming over his own face.

"I expect him every instant, sir," said Arabella. "I persuaded him to take a walk this morning. He is very low and wretched at not having heard from his father."

"Low, is he?" said the old gentlemen. "Serve him right!"

"He feels it on my account, I am afraid," said Arabella; "and indeed, sir, I feel it deeply on his. I have been the sole means of bringing him to his present condition."

"Don't mind it on his account, my dear," said the old gentleman. "It serves him right. I am glad of it — actually glad of it, as far as he is concerned."

The words were scarcely out of the old gentleman's lips, when footsteps were heard ascending the stairs, which he and Arabella seemed both to recognise at the same moment. The little gentleman turned pale; and, making a strong effort to appear composed, stood up, as Mr. Winkle entered the room.

"Father!" cried Mr. Winkle, recoiling in amazement.

"Yes, sir," replied the little old gentleman. "Well, sir, what have you got to say to me?" [The British Household Edition, Chapter LVI, “An important Conference takes place between Mr. Pickwick and Samuel Weller, at which his Parent assists. An old Gentleman in a snuff-coloured suit arrives unexpectedly,” pp. 395-396]

Commentary: A Family Reunion

Dodson and Fogg — to say nothing of their client, Mrs. Bardell — disposed of, and Jingle and his mulberry-liveried servant Job Trotter assisted with passage to Demerara in the West Indies, Dickens in Chapter LVI turns the reader's attention to the resolution of the novel's romantic plots (i. e., the relationships between Nathaniel Winkle and Arabella Allen; Augustus Snodgrass and Emily Winkle; and Sam Weller and the Ipswich maid, Mary, who thus becomes "Mary Weller," the name of the young woman who was young Charles Dickens's nurse), and the disposition of Tony's Weller's inheritance from his late wife, a wealthy publican.

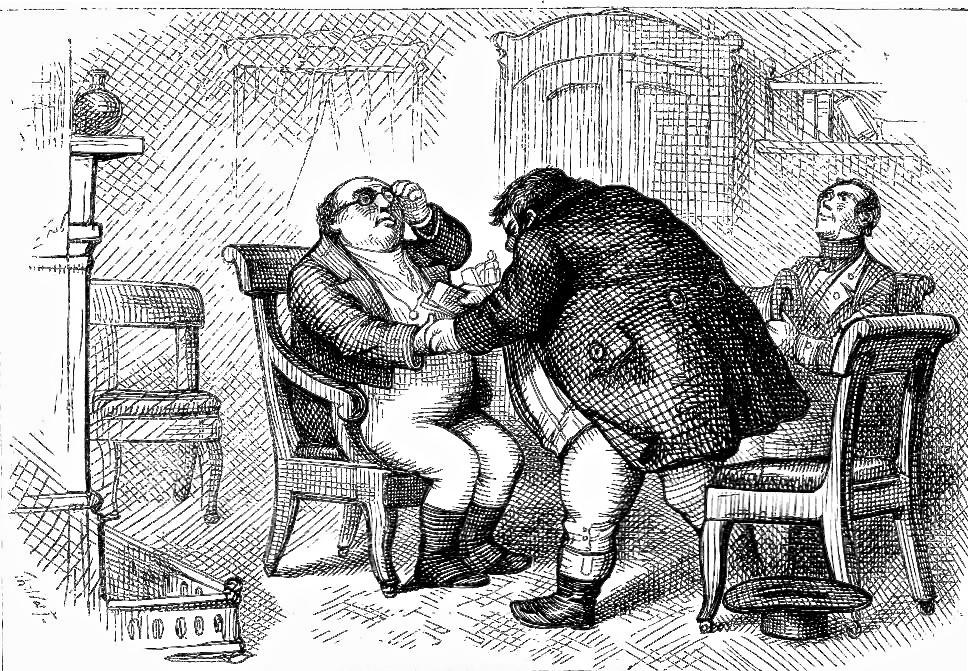

"All I can say is, just you keep it till I ask you for it again" by Thomas Nast in the American Household Edition (1873).

In the American Household Edition, not much interested in these romances, Thomas Nast realises instead the passage in Ch. LVI concerning Tony Weller's consigning his estate to Pickwick for investment in the antepenultimate illustration, "All I can say is, just you keep it till I ask you for it again" (page 324):

"This here money," said Sam, with a little hesitation, "he's anxious to put someveres, vere he knows it'll be safe, and I'm wery anxious too, for if he keeps it, he'll go a-lendin' it to somebody, or inwestin' property in horses, or droppin' his pocket-book down an airy, or makin' a Egyptian mummy of his-self in some vay or another."

"Wery good, Samivel," observed Mr. Weller, in as complacent a manner as if Sam had been passing the highest eulogiums on his prudence and foresight. "Wery good."

"For vich reasons," continued Sam, plucking nervously at the brim of his hat — "for vich reasons, he's drawn it out to-day, and come here vith me to say, leastvays to offer, or in other vords —"

"To say this here," said the elder Mr. Weller impatiently, "that it ain't o' no use to me. I'm a-goin' to vork a coach reg'lar, and ha'n't got noveres to keep it in, unless I vos to pay the guard for takin' care on it, or to put it in vun o' the coach pockets, vich 'ud be a temptation to the insides. If you'll take care on it for me, sir, I shall be wery much obliged to you. P'raps," said Mr. Weller, walking up to Mr. Pickwick and whispering in his ear — "p'raps it'll go a little vay towards the expenses o' that 'ere conwiction. All I say is, just you keep it till I ask you for it again." With these words, Mr. Weller placed the pocket-book in Mr. Pickwick's hands, caught up his hat, and ran out of the room with a celerity scarcely to be expected from so corpulent a subject.

"Stop him, Sam!" exclaimed Mr. Pickwick earnestly. "Overtake him; bring him back instantly! Mr. Weller — here — come back!"

Sam saw that his master's injunctions were not to be disobeyed; and, catching his father by the arm as he was descending the stairs, dragged him back by main force.

"My good friend," said Mr. Pickwick, taking the old man by the hand, "your honest confidence overpowers me." [The American Household Edition, p. 323]

On the other hand, with a view to resolving in his narrative-pictorial program the many romances in progress at the end of the novel (and given the greater freedom of the Household Edition to address what he must have regarded as a deficiency in the original serial program of illustration of forty-four engravings), Phiz focuses on the reconciliation of Mr. Winkle and his son Nathaniel, and the old man's acceptance of Arabella as a daughter-in-law, in spite of what he considers to be his son's misconduct.

Although Nast's final illustrations round out the issue of the Weller investment in a relatively straight-forward manner, with "All I can say is, just you keep it till I ask you for it again", and while obliquely representing the multiple romances there is only the contemplative writer , Phiz lets one romantic relationship — that of Nathaniel Winkle and Arabella Allen — stand for all the novel's romantic relationships, including those between Sam and Mary, and between Augustus Snodgrass and Emily Wardle.

Even if Dickens places Tracy Tupman outside this magic circle of romance in the bachelor's retirement at Richmond, Nast implies that, after the dissolution of the Pickwick Club, Augustus Snodgrass returns to the isolation of poetic reverie, although the text makes plain that he is merely "occasionally abstracted and melancholy" (American Household Edition, p. 331, facing the illustration), presumably as he gazes out the window of his cottage at Dingley Dell, his inordinately large waste-paper basket beside his desk strongly suggests that the "melancholy" is mere writer's block. Whereas there is little continuity between Nast's Snodgrass and earlier representations of Pickwick's followers, Phiz strengthens the connection between the senior and junior Winkle in this final illustration by dressing them identically and making the father's face strongly resemble (with the inevitable signs of aging, such as a receding hairline) the son's, a resemblance which the reader remarks through the juxtaposition of the pair to the right. Between the male figures and Arabella a picture of a cottage dominates the space in the centre, implying a positive domestic and financial outcome for the newlyweds. For the sake of visual continuity, in this final illustration Phiz has endowed Arabella with the same face and expression seen in Mr. Pickwick could scarcely believe the evidence of his own senses and the same hairstyle glimpses in "My dear," said Mr. Pickwick, looking over the wall, and catching sight of Arabella on the other side. "Don't be frightened, my dear, 'tis only me.". The hairstyle alone connects the present image of the black-eyed beauty, Arabella Winkle, and the young woman behind one of the Wardle girls in the Christmas Eve party, however.

Commentary: The Relatively Minor Roles of Women in Dickens's Break-out Novel

Quite in keeping with the marriage motif of the concluding chapters, women appear more frequently in these final plates than in any previous series except the Dingley Dell Christmas woodcuts: no. 48 has two, no. 55 has two, and no. 57, one. Those illustrations with a significant proportion of young women include the frontispiece (no. 1), the election scene (no. 13), the garden party (no. 16), the ladies' seminary (no. 18), Lobbs's discovering Pipkin (no. 19), Pickwick surrounded by the young women at Wardle's (no. 28), Pickwick sliding (no. 30), Tony Weller's first assault of Stiggins (no. 33), and the card room at Bath (no. 35). The mature women in the second prison recognition scene, Mrs. Bardell screamed violently; Tommy roared; Mrs. Cluppins shrunk within herself; and Mrs. Sanders made off without more ado, dominate the right half of the scene, and equal the number of men. To view the matter another way, male characters dominate the action of all three Pickwick Papers narrative-pictorial sequences: in the original forty-four engravings, women appear as supporting characters in a few scenes such as Dr. Slammer's Defiance and Pickwick in chase of his hat, and in positions of importance in a very few, such as Mrs. Bardell faints in Mr. Pickwick's arms, and young women enter the program later than Sam Weller, in Mrs. Leo Hunter's fancy-dress dejeuner, and very rarely &mndash; as in The Unexpected Breaking Up of the Seminary for Young Ladies — do women actually dominate a scene. Accordingly, might one conclude that, whatever the appeal of its humour, pathos, and romance, the novel in serial reified the nineteenth-century doctrine of separate spheres, with the external world of business, law, commerce, and politics dominated by upper- and upper-middle-class males, and the "internal" world of child-rearing, family, cooking, and domestic activity generally dominated by females.

In the overwhelming number of the 1836-37 series of forty-four illustrations, Seymour and Browne depict the story's male characters as consistently active: travelling, consuming food and especially drink, combative, and constantly having new experiences; in contrast, the female characters are passive, often attractive ornaments to the scene, and they are almost always depicted in domestic situations (many of these being indoors: dances, drawing-rooms, kitchens, dining-rooms, card-rooms, and tap-rooms), in which situations they are usually serving men, either by being spectacles of beauty or by providing food and drink, as in Mary and the Fat Boy. In most of the original serial confrontations illustrated, the antagonists are male; in social situations, the principals are largely male, although the spectators may be both male and female (if present at altercations, the women are often passively escaping by fainting, as in The Rival Editors). Only very late in the original program do the young women appear prominently, the turning point being Mr. Winkle Returns under extraordinary circumstances. Most notably, attractive women are objects of male courtship and appropriation, as in The Ghostly Passengers of a Ghost of a Mail. Indeed, in seven of the original forty-four illustrations women of any age or condition are not present at all.

In this respect, the British Household Edition is similar in its construction of women as objects of beauty and purveyors of masculine comforts, but women appear in thirty of the fifty-seven woodcuts, six of which they actually dominate. Perhaps owing to the growing literacy rates among females, then, the British Household Edition of The Pickwick Papers represents something of an advance for women; although the text has, of course, not changed over forty years, the program of illustration has admitted females in great numbers, perhaps a mute but palpable acknowledgement of the growing importance of the female readership in the latter part of the Victorian period. In Nast's program for Harper and Brothers, women rarely appear in prominent positions, for the American satirist seems to have conceived of the novel as an almost exclusively male story in which women, even if present, consistently play subordinate roles — female characters appear in only one-third of Nast's fifty-two illustrations, in fact. Rarely does Nast show a capacity for depicting physically attractive female characters: women appear in supporting roles in his frontispiece, Tupman's courting Rachael Wardle (no. 13), "Mr. Winkle, take your hands off me. Mr. Pickwick, let me go, sir!" (no. 15), Pickwick's obliquely sounding out Mrs. Bardell about hiring Sam (no. 17), the candidate's kissing infants at Eatanswill (no. 18), Pickwick's inadvertent trespass in the bedroom of Peter Magnus's fiancée in her hotel room (no. 27), "What is the meaning of this, sir?" (no. 28), in Muzzle's kitchen (no. 29), "I suppose you've heard what's going forward, Mr. Weller?" said Mrs. Bardell (no. 30), Sam's interrupting Stiggins and his mother-in-law at the Marquis of Granby (no. 31), and most notably the four women in Nast's version of the Dingley Dell Christmas party, It was a pleasant thing to see Mr. Pickwick in the center of this group (no. 32), in which two young women catch the protagonist under the misteltoe, and "Lord do adun, Mr. Weller" (no. 43). In the background of the ice-sliding at Dingley Dell (no. 34), and in the scene in front of the window of card-shop (no. 37), at church (no. 42), and in the Wellers' visit with Stiggins to the Fleet (no. 46), as in most of the earlier Nast woodcuts, the female characters play minor roles, so that the overall impression in the American Household Edition is of a middle-class society in which women play a relatively insignificant part outside the home. In fact, in less than ten of Nast's illustrations do women appear at all, and, if it is fair to judge by such a woodcut as "Will you have some of this?" said the Fat Boy (no. 49), Nast had neither a predilection nor the ability to draft feminine beauty and distinguish female characters, in contrast to Phiz, who throughout his career seems to have enjoyed a fair feminine face and form, and to have been able to draft these effectively.

Related Material

- The complete list of illustrations by Seymour and Phiz for the original edition

- An introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

Other artists who illustrated this work, 1836-1910

- Robert Seymour (1836)

- Thomas Onwhyn (1837)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1861)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1867)

- Thomas Nast (1873)

- Harry Furniss (1910)

- Clayton J. Clarke's Extra Illustrations for Player's Cigarettes (1910)

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the images, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File and Checkmark Books, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Robert Seymour, Robert Buss, and Phiz. London: Chapman and Hall, November 1837. With 32 additional illustrations by Thomas Onwhyn (London: E. Grattan, April-November 1837).

_____. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. Vol. 1.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. The Household Edition. 16 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1873. Vol. 4.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. Vol. 6.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 2.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens.2 vols. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. I.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Johnannsen, Albert. "The Posthumous Papers of The Pickwick Club." Phiz Illustrations from the Novels of Charles Dickens. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; Toronto: The University of Toronto Press, 1956. Pp. 1-74.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 2. "The Beginnings of 'Phiz': Pickwick, Nickleby, and the Emergence from Caricature." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. Pp. 24-50.

Created 23 April 2012

Last modified 3 April 2024