Sandys and Victorian Classicism

Sandys was influenced by a number of contemporary sources. One was the emerging neo-classicism of the 1860s, as exemplified by the paintings of Frederick Leighton, G.F. Watts, and Edward Poynter. He characteristically manipulates the styles of these artists, creating a version of Arcadian idealism which, while clearly part of a wider discourse, is not bound by it and might even be read as a subversion of the mode.

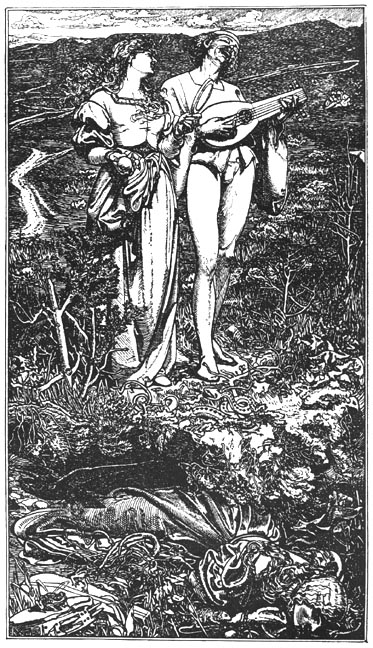

Sandys preserves the antiquarian trappings of the neo-classicists in the form of the architecture and costumes, but injects his own sense of narrative urgency and psychological implication. Though decorative in the manner of Leighton, his illustrations focus absolutely on defining the emotional situation. In Cassandra and Helen the two characters argue petulantly, an image of a ruined idyll, with writhing arabesques in the background suggesting the conflict between them. The Advent of Winter, is also an unusual reflection on contemporary neo-classicism. In this design the style’s static form is replaced by a character walking away from the picture plane, her robes blowing in the wind and the foreground occupied by some swirling plants.

Sandys and Pre-Raphaelitism

Left to right: (a) Sandys, The Nightmare. (b) John Everett Millais, A Dream of the Past -- Sir Isumbras at the Ford. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

More important, though, was the influence of Pre-Raphaelitism. Although he had ridiculed the Brotherhood in his satirical print, The Nightmare, Sandys was essentially a second-generation Pre-Raphaelite, whose imagery draws on the iconographies developed by D. G. Rossetti, J.E. Millais, and William Holman Hunt. Sandys particularly responds to the influence of Rossetti, who was a personal friend and with whom he briefly shared accommodation. Sandys presents his own reading of the older artist’s style and there are numerous points of connection between their works.

Left to right: (a) Rosamund. (b) St Cecilia. (c) Amor Mundi.

Some of this is practically a matter of borrowing, and is close to plagiarism. For example, the drawing of the organ-pipes in Yet once more surely alludes to the curious perspective with which a similar organ is shown in Rossetti’s St Cecilia for Tennyson’s ‘The Palace of Art’ (1857, p.113). The Moxon Tennyson is also the source for Rosamund, this time appropriated from the drawing of the female figure in Rossetti’s Mariana in the South (Tennyson, p.82). The Rossettian idea of the fleshy women is taken up by Sandys, who reproduces the key signs of long swirling hair, well-defined jaw, swan-like neck and pouting lips. This type features not only in the illustrations just mentioned, but also in Amor Mundi and If, where the two woman are monumental figures in the manner of Rossetti’s portraits of the sixties.

Sandys and the Rosetian woman — left to right: (a) If he would come to-day. (b) Rossetti's Lady Lilith and The Blessed Damozel .

Rossetti’s influence also informs Sandys’s fascination with intricate accessories. Like Rossetti’s illustrations, those of Sandys are crammed with Pre-Raphaelite esoterica and decorative items. In the foreground of Rosamund, held behind tiny straps, are a pair of scissors, some notes and an engraving burin (no doubt a private joke referring to wood-engraving), a burning brazier, a carved relief of the Virgin Mary and Child, a rosary and a book-mark hanging out of a book; in the middle-ground, a crucifix, radiating lamp, decorative wallpaper; and in the background a goblet, stool, two vases, another burning lamp and, of course, the figure of the king. This dense catalogue recalls the crowding of the surfaces in Rossetti’s art of the fifties, and there is no doubt that Sandys sets out to generate a mysterious, fairy-tale atmosphere by replicating the curiosity-shop iconographies of his mentor. Such imagery endows Sandys’s designs the sort of dream-like otherworldliness that is so much a part of Rossettian fantasy.

Left to right: (a) Life's Journey. (b) The Old Chartist . (c) W. Holman Hunt's The Awakening Conscience

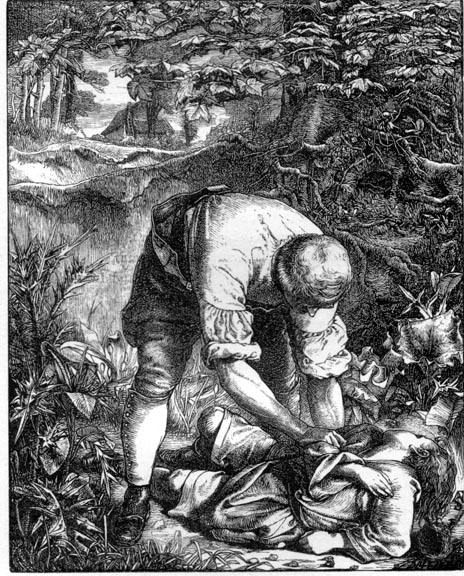

At the same time, he was heavily influenced by the emphasis on verisimilitude and copying from nature. His exemplar this time was Holman Hunt, whose densely detailed paintings, such as The Awakening Conscience(1856), provide a clear inspiration for the microscopic particularization that appears in all of Sandys’s designs. Particularly fine examples are Life’s Journey and The Old Chartist, both of which are figured as a naturalist’s catalogue, an assembling of details that shows the backgrounds in as much detail as the foregrounds. In The Old Chartist, for instance, the grasses, ivies and dock leaves are individually show as discrete items in the manner of Holman Hunt, while it is also possible to see tiny details in the far distance, including a wood with felled trees and a church. In between the two, the artist registers the textures of the trees and even the grain on the rickety bridge crossing the stream.

Such obsessive representation, in the manner of first-state Pre-Raphaelitism, features in all of the illustrations’ landscapes, which are lovingly based on landscapes in East Anglia; speaking of the background to Until her death the artist explains to the Dalziels that it was ‘exact, literal …It was drawn on the spot’ (Cooke, p.180). As Betty Elzea has shown in her catalogue raisonné, Sandys always copied directly from nature, did numerous studies and sketches, and never resorted to lay figures or copy-books; as in the work of his Pre-Raphaelite colleagues, everything seen in his images is indeed a studied transcript of the tangible world.

Yet, in the manner of Pre-Raphaelitism, the detail is more than ‘copying from nature’. Following the example of Hunt and Millais, Sandys fuses nature and idea in the form of ‘symbolic realism’, creating the effect, as William Michael Rossetti describes it, of ‘small actualities mode vocal of lofty meanings’ (p.18). In Sandys’s designs, as in those of the Pre-Raphaelites, ‘facts’ are also emblems, signs of the real world and signs of other meanings. Indeed, all of his designs on wood deploy legible iconographies: in Sleep,notably, the window symbolizes the soul’s release from earthly cares, a passageway to God; the flowers on the ledge signal resurrection and the return to nature; and the tiny detail of the river, glimpsed in the far distance, is a traditional Victorian symbol of the soul’s journey that leads to the universal sea. Amor Mundi, Until her death and other illustrations deploy parallel vocabularies, and can be read in the manner of Victorian painting.

Left to right: (a) Until Her Death. (b) Death on the Barricades from Auch ein Totentanz [Another Dance of Death].

Another influence was German illustration of the thirties and forties. Like many of his contemporaries, Sandys drew heavily on the morbid imagery of Alfred Rethel, especially Another Dance of Death (1847). With its representation of animated corpses and skeletons, Rethel defines and iconography of death that Sandys re-works in Until her death, Yet once more, and Amor Mundi. Death the friend, Rethel’s wood-engraving of 1851, is another influence, and a source of Sleep. The underlying influence was of course Dürer, and Sandys was indebted, in Until her death, to Melancholia (1514).

It short, Sandys engages with a series of contemporary movements. Though frequently described as an original voice, his art is at least in part a sophisticated manipulation of stylistic tendencies of the time. Interestingly, he is always today bracketed as a ‘Pre-Raphaelite illustrator’ (the typography adopted by Goldman and Suriano), although in his own time he was regarded as a ‘Germanic artist’. His relationship with classicism was not observed, and is barely noted today.

His art remains problematic, a combination of a distinct tonal quality, intense drawing, and a synthesis of contemporary influences. Positioned in the mid-Victorian period at a moment of change and development, he absorbs those changes and puts them at the service of a small corpus of themes. Commissioned to visualize mainly inferior writing, he uses the task of illustration as a means to explore his own concerns.

In another sense, however, his art provides a link between the Pre-Raphaelites and the later developments of Art Nouveau. Critics such as John Russell Taylor have noted the connection between Sandys and Charles Ricketts and also between Sandys and the art of Laurence Housman (pp.44–45). Taylor does not make his point explicit, but there can be little doubt, it seems to me, that the sinuous arabesques deployed by Sandys have a direct influence on the style of both of these later practitioners. The ‘flaming line’ (perhaps in imitation of William Blake’s designs) in the background to Cassandra and Helen is surely an influence on the swirling lines of Housman, and the treatment of the flames in Rosamund and again in the Death of King Warwulf are likewise motifs that seem of the nineties rather than the sixties. At once decorative and expressionistic, Sandys’s dramatic illustrations might ultimately be transformed, in a process of appropriation and change, into the pleasing ornateness of British Art Nouveau.

Last modified 15 July 2013