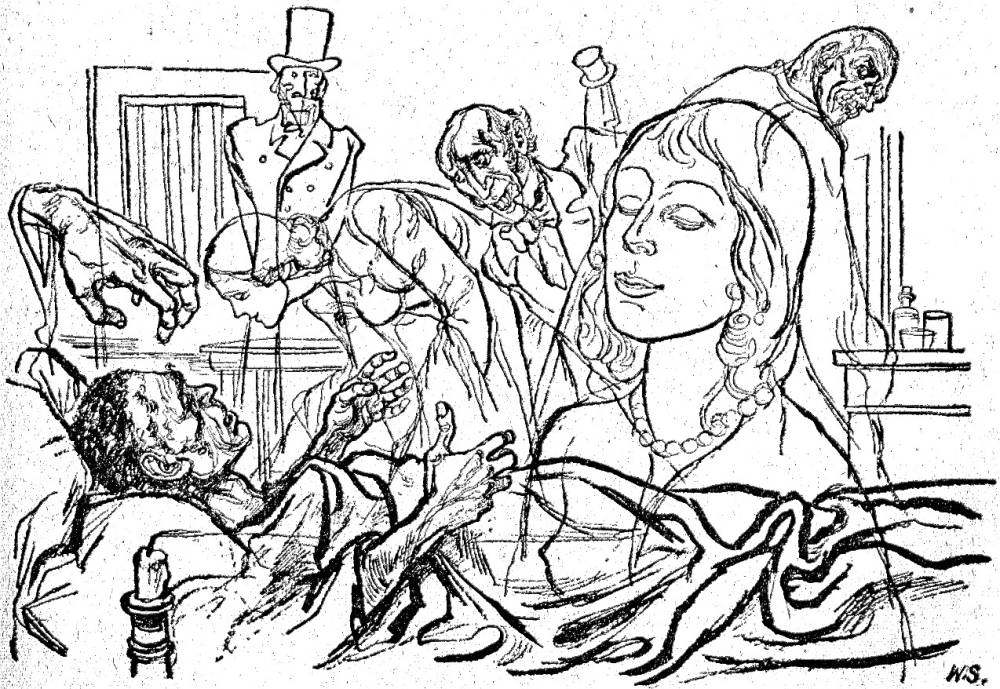

Dr. Candy's Delirium — uncaptioned vignette for the "The Story. Second Period," positioned in "The Fourth Narrative. Extracted from the Journal of Ezra Jennings," p. 373, in the Doubleday (New York) 1946 edition of The Moonstone. 7.1 x 10.4 cm. [Doubtless feeling guilty about having surreptitiously administered a draught of laudanum to counteract the effects of nicotine withdrawal in Franklin Blake after the birthday dinner, Dr. Candy is visited by phantasms in his fever. His contracting the deadly fever and subsequently being unable to recall what he did to Blake (with Godfrey Ablewhite's assistance) is a coincidence of Dickensian proportions necessary to drive the plot forward and ultimately to exonerate Blake of the theft of the Moonstone.] Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Suggested by the Illustration

Ezra Jennings took up his notes from the table, and placed them in my hands.

"Mr. Blake,"he said, “if you read those notes now, by the light which my questions and your answers have thrown on them, you will make two astounding discoveries concerning yourself. You will find — First, that you entered Miss Verinder's sitting-room and took the Diamond, in a state of trance, produced by opium. Secondly, that the opium was given to you by Mr. Candy — without your own knowledge — as a practical refutation of the opinions which you had expressed to him at the birthday dinner."

I sat with the papers in my hand completely stupefied.

"Try and forgive poor Mr. Candy," said the assistant gently. "He has done dreadful mischief, I own; but he has done it innocently. If you will look at the notes, you will see that — but for his illness — he would have returned to Lady Verinder's the morning after the party, and would have acknowledged the trick that he had played you. Miss Verinder would have heard of it, and Miss Verinder would have questioned him — and the truth which has laid hidden for a year would have been discovered in a day."

I began to regain my self-possession. "Mr. Candy is beyond the reach of my resentment," I said angrily. "But the trick that he played me is not the less an act of treachery, for all that. I may forgive, but I shall not forget it."

"Every medical man commits that act of treachery, Mr. Blake, in the course of his practice. The ignorant distrust of opium (in England) is by no means confined to the lower and less cultivated classes. Every doctor in large practice finds himself, every now and then, obliged to deceive his patients, as Mr. Candy deceived you. I don't defend the folly of playing you a trick under the circumstances. I only plead with you for a more accurate and more merciful construction of motives."

"How was it done?" I asked. "Who gave me the laudanum, without my knowing it myself?"

"I am not able to tell you. Nothing relating to that part of the matter dropped from Mr. Candy's lips, all through his illness. Perhaps your own memory may point to the person to be suspected.

"No."

"It is useless, in that case, to pursue the inquiry. The laudanum was secretly given to you in some way. Let us leave it there, and go on to matters of more immediate importance. Read my notes, if you can. Familiarise your mind with what has happened in the past. I have something very bold and very startling to propose to you, which relates to the future."

Those last words roused me.

"I looked at the papers, in the order in which Ezra Jennings had placed them in my hands. The paper which contained the smaller quantity of writing was the uppermost of the two. On this, the disconnected words, and fragments of sentences, which had dropped from Mr. Candy in his delirium, appeared as follows:

"... Mr. Franklin Blake ... and agreeable ... down a peg ... medicine ... confesses ... sleep at night ... tell him ... out of order ... medicine ... he tells me ... and groping in the dark mean one and the same thing ... all the company at the dinner-table ... I say ... groping after sleep ... nothing but medicine ... he says ... leading the blind ... know what it means ... witty ... a night's rest in spite of his teeth ... wants sleep ... Lady Verinder's medicine chest ... five-and-twenty minims ... without his knowing it ... to-morrow morning ... Well, Mr. Blake ... medicine to-day ... never ... without it ... out, Mr. Candy ... excellent ... without it ... down on him ... truth ... something besides ... excellent ... dose of laudanum, sir ... bed ... what ... medicine now."

"There, the first of the two sheets of paper came to an end. I handed it back to Ezra Jennings.

"That is what you heard at his bedside?" I said.

"Literally and exactly what I heard,” he answered—“except that the epetitions are not transferred here from my short-hand notes. He reiterated certain words and phrases a dozen times over, fifty times over, just as he attached more or less importance to the idea which they represented. The repetitions, in this sense, were of some assistance to me in putting together those fragments. Don't suppose," he added, pointing to the second sheet of paper, "that I claim to have reproduced the expressions which Mr. Candy himself would have used if he had been capable of speaking connectedly. I only say that I have penetrated through the obstacle of the disconnected expression, to the thought which was underlying it connectedly all the time. Judge for yourself."

I turned to the second sheet of paper, which I now knew to be the key to the first.

"Once more, Mr. Candy's wanderings appeared, copied in black ink; the intervals between the phrases being filled up by Ezra Jennings in red ink. I reproduce the result here, in one plain form; the original language and the interpretation of it coming close enough together in these pages to be easily compared and verified.

"... Mr. Franklin Blake is clever and agreeable, but he wants taking down a peg when he talks of medicine. He confesses that he has been suffering from want of sleep at night. I tell him that his nerves are out of order, and that he ought to take medicine. He tells me that taking medicine and groping in the dark mean one and the same thing. This before all the company at the dinner-table. I say to him, you are groping after sleep, and nothing but medicine can help you to find it. He says to me, I have heard of the blind leading the blind, and now I know what it means. Witty — but I can give him a night's rest in spite of his teeth. He really wants sleep; and Lady Verinder's medicine chest is at my disposal. Give him five-and-twenty minims of laudanum to-night, without his knowing it; and then call to-morrow morning. 'Well, Mr. Blake, will you try a little medicine to-day? You will never sleep without it.' — 'There you are out, Mr. Candy: I have had an excellent night's rest without it.' Then, come down on him with the truth! ‘You have had something besides an excellent night’s rest; you had a dose of laudanum, sir, before you went to bed. What do you say to the art of medicine, now?'"— "The Second Period. The Truth Discovered (1848-1849). Third Narrative, Contributed by Franklin Blake," Chapter 10, p. 360-363.

Commentary

Although the Harper's Weekly illustrators were competent artists, their conceptions of the characters are limited by pre-Freudian thinking about the nature of human consciousness. Indeed, although they show the results of Dr. Candy's illness, they did not and probably could not provide an image of what he was experiencing in his feverous state. The figures in Dr. Candy's delirium show that William Sharp was aware of the psychological complexity of the material he chose to illustrate, so that the recumbent figure of the suffering Dr. Candy is solid and therefore physically present, whereas the phantasms are sketched in, charming and even seductive, but confusing in their variety: he reaches up at a young woman bending over him, and that same young woman (possibly Rachel verinder) is repeated in the right foreground; in contrast, the three men in his dream are hideous manifestations of his own feelings of vanity, wounded professional pride, and determination to punish Franklin Blake for his presumptious criticism of medicine. The point hand above the dreamer's head may represent self-accusation or guilt at how he abused his professional knowledge in order to chastise Franklin Blake, for he did not have the patient's informed consent to administer the laudanum.

Relevant Serial Illustrations, 1868

Left: Franklin Blake is shocked to see the deterioration in Dr. Candy's condition, "He started impulsively to his feet and looked at me." (27 June 1868, p. 405).Centre: The original 1868 Jewett and C. B. illustration of Ezra Jennings: "Have you been accustomed to the use of laudanum?" (3 July 1868). Right: Uncaptioned headnote vignette, Franklin Blake reading Ezra Jennings' notes (11 July 1868, p. 437). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Related Materials

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- Introduction to the Sixty-six Harper's Weekly Illustrations for The Moonstone (1868)

- The Harper's Weekly Illustrations for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone (1868)

- George Du Maurier, "Do you think a young lady's advice worth having?" — p. 94.

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- 1910 illustrations by Alfred Pearse for The Moonstone.

Bibliography

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. with sixty-six illustrations. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. Vol. 12 (1868), 4 January through 8 August, pp. 5-503.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. All the Year Round. 1 January-8 August 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Novel. With many illustrations. First edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, [July] 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Novel. With 19 illustrations. Second edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1874.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by George Du Maurier and F. A. Fraser. London: Chatto and Windus, 1890.

_________. The Moonstone. With 19 illustrations. The Works of Wilkie Collins. New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, 1900. Volumes 6 and 7.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. With four illustrations by John Sloan. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1908.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by A. S. Pearse. London & Glasgow: Collins, 1910, rpt. 1930.

_________. The Moonstone. Illustrated by William Sharp. New York: Doubleday, 1946.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. With nine illustrations by Edwin La Dell. London: Folio Society, 1951.

Karl, Frederick R. "Introduction." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Scarborough, Ontario: Signet, 1984. Pp. 1-21.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review Volume 42, Number 3 (Fall 2009): pp. 207-243. Accessed 1 July 2016. http://englishnovel2.qwriting.qc.cuny.edu/files/2014/01/42.3.leighton-moonstone-serializatation.pdf

Nayder, Lillian. Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, & Victorian Authorship. London and Ithaca, NY: Cornll U. P., 2001.

Peters, Catherine. The King of the Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins. London: Minerva, 1991.

Reed, John R. "English Imperialism and the Unacknowledged crime of The Moonstone." Clio 2, 3 (June, 1973): 281-290.

Richardson, Betty. "Prisons and Prison Reform." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. London and New York: Garland, 1988. Pp. 638-640.

Stewart, J. I. M. "Introduction." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966, rpt. 1973. Pp. 7-24.

Stewart, J. I. M. "A Note on Sources." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966, rpt. 1973. Pp. 527-8.

Vann, J. Don. "The Moonstone in All the Year Round, 4 January-8 1868." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 48-50.

Winter, William. "Wilkie Collins." Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard, & Co., 1909. Pp. 203-219.

Last updated 1 November 2016