We take public parks for granted now, but they only go back to the nineteenth century. Moor Park in Preston, dating from 1833, is widely seen as the first. Most others were established in the later Victorian era, as great estates were broken up, and civic authorities bought their land. Their aim was an idealistic one: to offer amenities that would improve the physical, mental and moral well-being of the townsfolk, and help to bring communities together. In most respects, Ellington Park is a typical example of this movement, and this short book about it is instructive on that score alone. But the park also has some unique points, and these add considerably both to the park's and the book's appeal.

The first such point is the park's connection with the architect A. W. N. Pugin. The author, Catriona Blaker, is best known for her involvement with the Pugin Society, of which she was a co-founder in 1995. The society's publications and programmes of activities have helped enormously to promote the appreciation of Pugin's work and influence. Like Pugin himself, the society is a-brim with enthusiasm, and it is no coincidence that some of it has spilled over into this celebratory account. Pugin and his second wife Louisa lived in a cottage on the old Ellington estate in 1834, when the inspirational Gothic Revivalist was delighted to discover in the garden the remains of a fourteenth-century chapel. He settled down in Ramsgate later on, building his own house there in 1844-45 for his third wife Jane and their family. The style of Pugin's iconic Grange may even have influenced the design of the park-keeper's lodge.

When the Ellington estate, with its main house and twelve-acre parcel of land, came on the market in 1892, the Ramsgate Corporation bought it for the then princely sum of £12,000. Pugin's brief stay in Ellington Cottage is a small but pleasing part of the park's history. Another part is more sensational but less wholesome: in the seventeenth century, the main house itself was the scene of a particularly gruesome crime, when its current owner did away with his wife in a fit of drunken rage. Nothing remains to bear witness to the episode because the old Ellington House was later demolished and rebuilt on another part of the estate. When the Corporation took over, there was talk of turning the more recent establishment into a museum, but, for better or for worse, this one too was demolished.

Starting anew, the Corporation installed all the usual features of such a space: a pleasant terrace bordered with flowers and a retaining wall (thought to be constructed with knapped flint from the old house), a fountain and a drinking fountain, a bandstand, shelters, benches, a lake with an ornamental bridge, a menagerie and an aviary. Not all of these have survived. The original Doulton fountain was moved to make way for a new bandstand, the lake was filled in to provide a rockery, and so on. Although the park-keeper's lodge is still there, it was sold to private owners. Sometimes the change was all to the good. The new bandstand, dating from 1899 and recently restored, is rightly described here as "the jewel in the crown" of the park today: it was, we learn, "Pattern no. 279 from Macfarlane's catalogue" (23). Specimens of Macfarlane's decorative cast iron can be see all over the country, and indeed the world. Sometimes, losses have been made good in ways which appeal to today's visitors: one recent development has been the construction of a wildlife area, and a new pond.

Illustrations from the book, sourced from the archives of the "Friends of Ellington Park." Left: View of the terrace prior to 1896, showing the original bandstand at the side, with some "rather temporary looking extensions" behind it (p. 21). Right: The lost Doulton fountain, when it was the park's central feature. The man in uniform behind it was the park-keeper. The old bandstand can again be seen beyond it (p. 25).

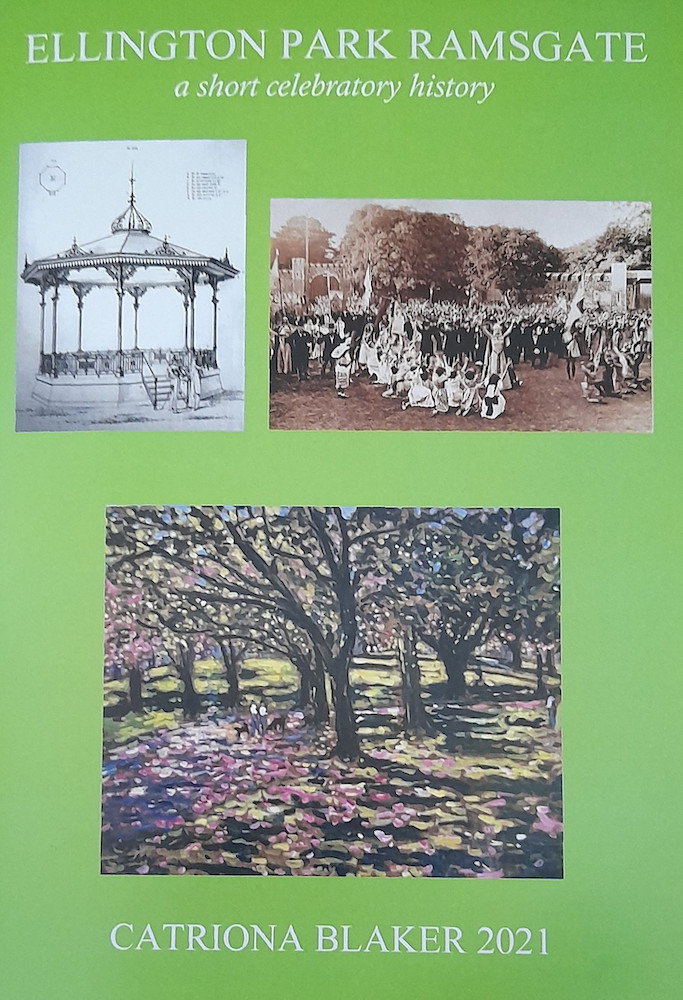

Over the years, the park has fulfilled all the Corporation's original aims. As well as providing pleasant walks, views and a refreshing green space for its visitors, it quickly became a place where the community could gather on special occasions. Pageants, fairs, firework displays, open-air theatre, concerts, carol-singing and other activities have all been enjoyed here. Art in the park, a common and very welcome slogan these days, also flourishes, and another of the unique points here is that some of the many illustrations are etchings and paintings of the park by the author's husband, Michael Blaker. Sadly, Michael passed away in 2018, but he had been a valued contributor to the Victorian Web, and it is heartwarming to see his work in this new context.

Two more illustrations showing the park in more recent times. Left: The bandstand of 1899, now "gloriously restored" (23), facing p. 24. Right: Autumn in the Park, oil on board, by Michael Blaker (p. 49), showing some of the park's fine trees, both old and new, in their most colourful dress. Photographs by Catriona Blaker.

Thanks to the volunteer group, "Friends of Ellington Park," and heritage grants, regeneration of this Ramsgate attraction continues. As everyone knows, maintenance and improvements are both costly. Funds arising from sales of the book will all go to the "Friends," so that they can carry on the Victorians' good work.

Bibliography

Blaker, Catriona. Ellington Park Ramsgate: A Short Celebratory History. Ramsgate: Potmetal Press, 2021. 52 pp. Available from the author at catrona@tiscali.co.uk, for £6.00, including postage.

Created 4 July 2022