This is a condensed and edited version of a very interesting discussion on the window by Ray Brown in Stained Glass Australia: Historical Stained Glass Windows. Where necessary, the original footnotes have been incorporated. We are very grateful to Ray for allowing us to draw on his material. Photographs © Ray Brown, all rights reserved. [Click on the images to enlarge them]. — Jacqueline Banerjee

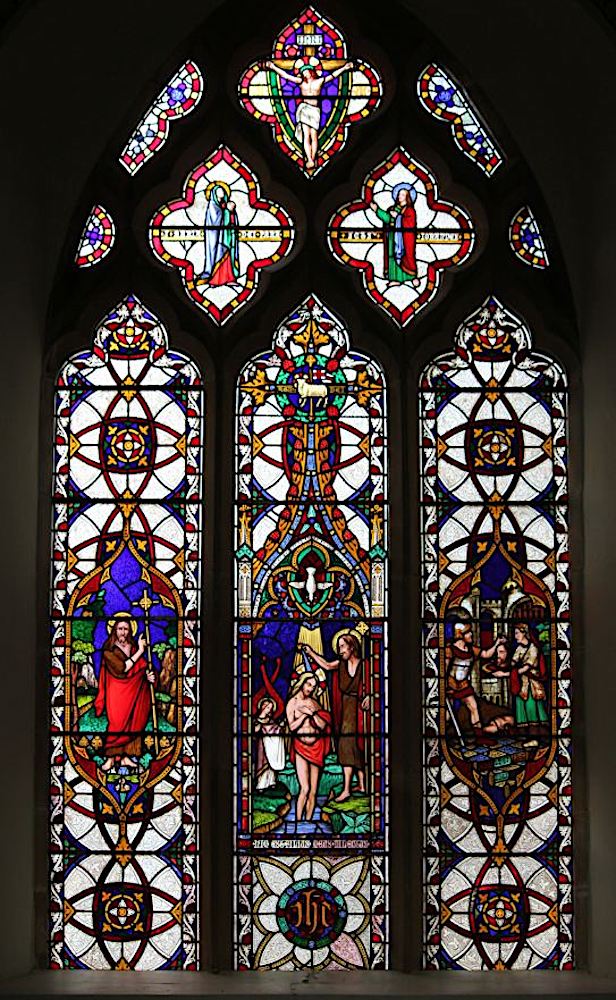

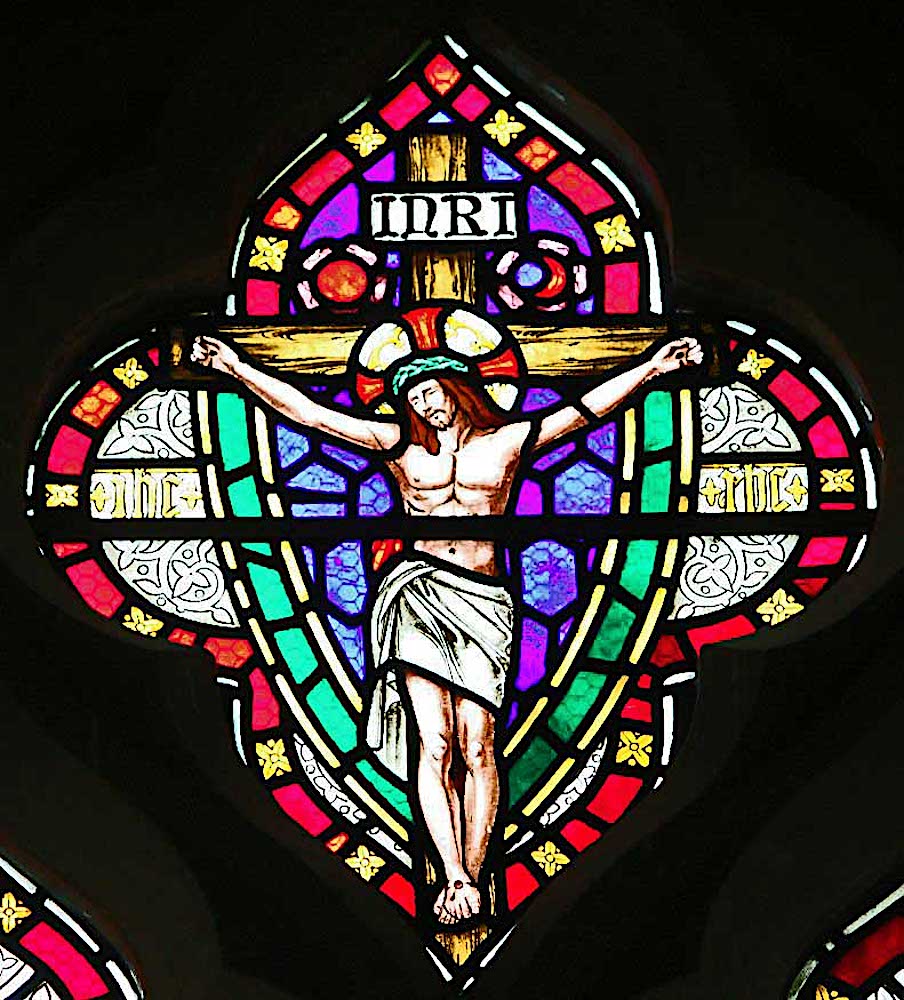

East Window, at St John the Baptist, Buckland, Tasmania, by Michael O'Connor, featuring the crucifixion of Jesus in the top tracery light, Mary and St John the Evangelist on either side in the lower tracery lights, and the life and death of St John the Baptist in the three main panels below. Nothing is very remarkable in this, except, as Ray Brown says, "the gory graphical detail of St John’s beheading." Not only is a soldier holding the severed head by the hair as he places it on a platter, in fulfilment of Salome's request, but the headless torso is seen on the ground, blood still pouring from the severed neck. Both the origins and the quality of this window have produced an extraordinary amount of controversy over many years.

As for its provenance, Brown describes and dismisses various myths surrounding O'Connor's work in the church — for example, that the stained glass came from pre-Reformation days — and quotes from A.L. Wayn of Lower Sandy Bay who stated in The Mercury, Hobart, on 5 January 1935 that the maker was, in fact, "O’Connor, of Berners Street, London" (8). Brown firmly supports this statement by citing an article about the church consecration published in the Hobart Courier of 23 January 1850, to the effect that "a large eastern window of three lights, and a smaller one of two lights in the northern side.... are filled with stained glass, the work of Mr. O’Connor, a London artist…" (2). Brown is, in fact, able to provide further proof of this in another letter in The Mercury, from 28 January 1935, in which the correspondent refers to "a letter written from London by [the first incumbent] Mr Cox to the Bishop in which he says: 'I have placed an order for the east window with the respectable and well-known firm of O’Connor'" (6).

Even the repairs to the glass became a matter of argument, again resolved by Brown, who found that they were effected in 1904 by stained glass firm in Tasmania itself.

The quality of the glass has also provoked debate. A write-up of Buckland in The Mercury of 4 April 1933 complained, "No painter would be permitted to show in any modern exhibition such distorted, angular, cramped, ridiculous figures, as our newest stained glass windows present to the eyes of wondering congregations" (12). But to another visitor, its beautiful colouring seems to have been result of using "crushed gems" (see The Advertiser, Friday 28 July 1950: 4). Brown is more sympathetic to the latter point of view, pointing out that indeed "ground glass, various minerals, such as cobalt, and even silver and gold are amongst the many materials that are sometimes used in small amounts to create certain colours and effects during the painting and firing process of the glass."

It is surprising that there was so much speculation about this stained glass, over such a long period, and wonderful that evidence was brought forward to settle its origins, even if different opinions are still entertained about the depiction of its figures.

Created 16 October 2023