"Macaulay, with unerring inaccuracy, called Hard Times 'sullen socialism.' If he had called it rampant anarchism, he would have been nearer the mark, if still wide of the target" — Hesketh Pearson, 212.

lthough he had launched his career as a writer in the 1830s with comic vignettes of London characters in Sketches by Boz and Pickwick Papers, by mid-century, however, Dickens's work as a quaint anecdotalist--"The Fielding of the Nineteenth Century"--was over. Gradually the vivacious young writer had become a satirical and sometimes bitter critic of social vices, as in Bleak House (published monthly from March 1852 to September 1853) and an analytical novelist trying to sift the meaning of his own anguished childhood and rise to stardom in David Copperfield (again, published monthly--from May 1849 to November 1850). The year prior to his attempting his first weekly serialization for his journal Household Words, Dickens had begun his celebrated public readings which brought to life such memorable characters as Scrooge, Fagin, Nancy, and Sykes. Three years prior to Hard Times his father (one of the originals of Copperfield's Wilkins Micawber) had died. Charles Dickens's third and final daughter, Dora, was born and died in 1850; his seventh and last child, a boy, had been born in 1852.

lthough he had launched his career as a writer in the 1830s with comic vignettes of London characters in Sketches by Boz and Pickwick Papers, by mid-century, however, Dickens's work as a quaint anecdotalist--"The Fielding of the Nineteenth Century"--was over. Gradually the vivacious young writer had become a satirical and sometimes bitter critic of social vices, as in Bleak House (published monthly from March 1852 to September 1853) and an analytical novelist trying to sift the meaning of his own anguished childhood and rise to stardom in David Copperfield (again, published monthly--from May 1849 to November 1850). The year prior to his attempting his first weekly serialization for his journal Household Words, Dickens had begun his celebrated public readings which brought to life such memorable characters as Scrooge, Fagin, Nancy, and Sykes. Three years prior to Hard Times his father (one of the originals of Copperfield's Wilkins Micawber) had died. Charles Dickens's third and final daughter, Dora, was born and died in 1850; his seventh and last child, a boy, had been born in 1852.

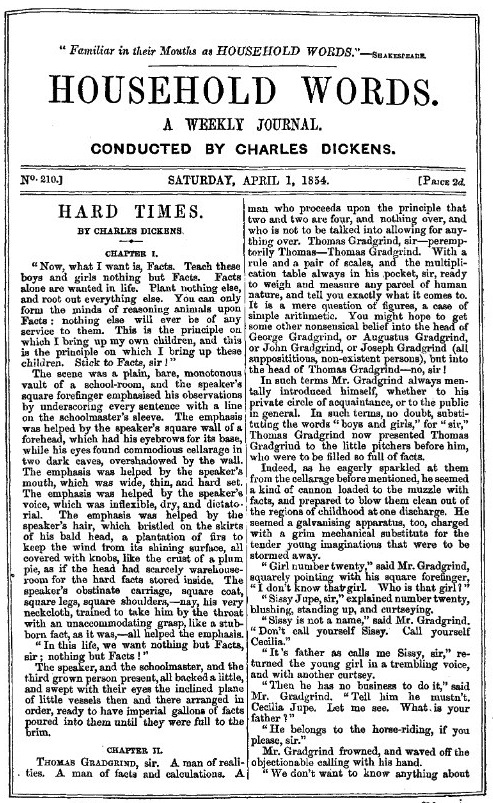

First page of the first instalment in Household Words, from a copy in Stanford University Library. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Thus, when, exhausted from the mammoth labour of writing Bleak House, he began writing his new industrial novel in January 1854, death, parents, parenting, and children were much on his mind. So, too, were the money morality of the factory system, the protracted mill strike at Preston in Lancashire, and the problems of the working poor: "They are born at the oar, and they live and die at it," he wrote to a correspondent. "Good God, what would we have of them!" Hard Times, serialised from 1 April to 12 August 1854, is set in the mythical Coketown (named after the coking coal used in the blast furnaces of northern England's industrial revolution), based in part on Preston, which he had visited in January of that year. With its blend of fairytale characters in modern dress and the moral indignation of investigative journalism, Hard Times more than doubled the circulation of Household Words. Dedicating the short novel to Carlyle, Dickens sought to expose the appalling conditions of life in the factory towns he had recently visited when investigating the Preston strike. He preached against unhealthy conditions in which the labouring poor lived, conditions enmgendered by the greed of factory owners, and "ridiculed the typical bureaucratic mentality which substituted scientific accuracy for imaginative reality, convinced that facts and figures were all-important, while fancies were beneath contempt" (Pearson, p. 211).

In terms of length, the average monthly instalment of a Dickens novel is 18,500 words, whereas the average weekly instalment of Hard Times runs a mere 5,000. At 117,400 words, Hard Timesis shorter than either 1859's A Tale of Two Cities (146,500 words) or 1861's Great Expectations (189,000 words), both serialized in Dickens's second weekly periodical, All The Year Round. Hard Times is also much shorter than its weekly predecessors, The Old Curiosity Shop (227,500 words) and Barnaby Rudge (263,650 words), both published in Master Humphrey's Clock (1840-1841). Since Dickens's average monthly novel runs 357,000 words, Hard Times is roughly one-third the length of his average monthly. It has roughly two dozen characters, half of whom are principals. The average length of a Dickens novel published in weekly instalments is roughly forty per cent that of a novel published monthly (1126 pages). Since the weekly Great Expectations has 59 episodes in as many chapters, and the monthly Dombey and Son has 62 episodes in as many chapters, what Dickens seems to have cut out of his weekly serialisations was not plot but character, there being only twenty characters in Hard Times, for example.

As Gerald Giles Grubb in "Dickens' Pattern of Weekly Serialization" (English Literary History 9: 141-156) notes, the proposal to publish Hard Times in weekly serial did not come from Dickens but from the printers of his magazine, Household Words, who were concerned about declining sales. Forster in his biography reports that the novel had the desired effect, more than doubling the journal's circulation. Even though Dickens, now forty-one, had hoped for a year's rest after his labours on Bleak House, he had written a children's history of England, edited articles for his weekly journal, and plunged into amateur theatricals after August, 1853. Acceding to his printers' proposal, he wrote the first page of Hard Times on 23 January, 1854.

The semi-annual meeting of the meeting of the joint proprietors of Household Words (established in 1850), determined to stem the magazine's sagging sales and profits, exhorted Dickens, its editor, to write a serialized novel for the weekly. In response to that December 28, 1853, resolution (Dickens having absented himself from the meeting to read A Christmas Carol and The Cricket on the Hearth in Birmingham), on January 20, 1854, he sent ten of twenty possible titles for the new novel to Forster, asking him to select the best three. Dickens also short-listed three: the common title between the two lists was Hard Times. On the 29th of January 1854, Dickens visited Preston, reporting by correspondence to Forster that the Lancashire industrial town was remarkable in respect to others of its kind only in its absence of smoke.This first 'Industrial' Dickens novel appears to be modelled in part on Elizabeth Gaskell's Ruth (published in three volumes in January, 1853), according to Norman Page in the November, 1971, issue of Notes and Queries. Mrs. Gaskell's Bradshaw, for example, corresponds to Dickens's Gradgrind. K. J. Fielding in "The Battle for Preston" suggests that Hard Times has its origin in the Preston weavers' strike, which began in October 1853, over the workers' demand for a ten per cent wage increase. The work stoppage idled some 20,000 mill workers for at least thirty-seven weeks. The Preston strike may also be reflected in the industrial novel North and South, which Dickens published for Mrs. Gaskell in Volume Ten of Household Words, immediately upon the conclusion of Hard Times in Volume Nine.

Like Mr. Gradgrind's prize pupil, Bitzer, Coketown is the product of Thomas Gradgrind's system of facts. It opposes the world of fancy and illusion that Sleary's circus (with whom we enter the town and the story) represents; its only purpose is to enrich the factory owners, epitomized by Josiah Bounderby. However, Bounderby is not the story's only villain: young Tom Gradgrind, amoral and egocentric (like Bitzer), uses Stephen Blackpool as a scapegoat; James Harthouse, the capable but indolent aristocrat, attempts to seduce Louisa; and Slackbridge, the union demagogue, ostracizes Stephen to maintain the honour and solidarity of Coketown's workers. The last of these villains is probably based on Grimshaw, an actual union agitator whom Dickens satirized on the article "On Strike" as "Gruffshaw."

Aside from its offering what K. J. Fielding terms "a comprehensive vision of [Dickens'] contemporary society" ("Practical Art" 270), Dickens's tenth novel, Hard Times for These Times (1 April-12 August, 1854) provides a glimpse into its author's moribund marital relations at the time. Married on 2 April, 1836, when Charles was just 24 and Catherine 20, daughter of Scottish literary man, the young Dickenses had begun having children almost right away. By the time he was 42, the couple had had eight children. "With a sharp twist of the knife of his imagination, his view of Catherine's incompetence, clumsiness, withdrawal from responsibility, and unsuitability as his wife appears in his depiction of Sephen Blackpool's alcoholic wife, from whom he is separated" (Kaplan 309-310). Although Charles and Catherine Dickens did not formalize their separation until May 1858, by 1854 Dickens felt himself trapped in a miserable marriage and yoked to an intellectual and aesthetic inferior for life. That deep dissatisfaction, that "want of something," lies behind the unsuitable marriages of Stephen Blackpool and of Louisa Bounderby, whose twin plights become dramatic essays about the need for humane divorce laws.

References

[Illustration source] Dickens, Charles. Hard Times. In Household Words, IX, 210: 141. Online at Stanford University's "Discovering Dickens: A Community Reading Project." Web. 1 April 2017.

Fielding, K. J. "The Battle for Preston." Dickensian 50 (September 1954): 159-162.

_____. "Dickens and the Department of Practical Art." Modern Language Review 48, 3 (July, 1953): 270-277.

Kaplan, Fred. Dickens: A Biography. New York: William Morrow, 1988.

Pearson, Hesketh. Dickens. London: Cassell, 1949.

Illustration added 1 April 2017