[The uppercase "W" comes from the print version of this essay. Page breaks are indicated in the following manner [263/264] so readers can cite locations in the original text. GPL]

HEN I first knew Thomas Hood, his star was but rising;

when I saw him last, he was on his death-bed; his

forty-six years of life from the cradle to the grave having

been passed in so weak a state of health, that day by day

there was perpetual dread that at any moment might "the

silver cord be loosed, and the golden bowl be broken." Continual bodily suffering was not the only trial to which this

fine spirit was subjected. The world heard no wail from

his lips; no appeal for sympathy ever came from his pen;

his high heart endured in silence; and, without a murmur of complaint, he died. Yet it is no secret now that for many years he had a

fierce struggle with poverty; enjoying no luxuries and few comforts; his

"means" derived from "daily toil for daily bread." A skeleton stood ever

beside his bed, mocking his "infinite jest and most excellent fancy:" converting into a succession of sobs those "flashes of merriment that were wont

to set the table in a roar." At the time when nearly every drawing-room, attic

and kitchen — when every class and order of society — was made merry and happy

by the brilliant fancies and genuine humour, of Thomas Hood, he was enduring

pain of body and anguish of mind. Nearly all his quaint conceits, his playful

sallies, and his sparks from words were given to the printer from the bed on which [135/136] he wrote, propped up by pillows; continually, continually, it was the same, up to the day that gave him freedom from the flesh.

HEN I first knew Thomas Hood, his star was but rising;

when I saw him last, he was on his death-bed; his

forty-six years of life from the cradle to the grave having

been passed in so weak a state of health, that day by day

there was perpetual dread that at any moment might "the

silver cord be loosed, and the golden bowl be broken." Continual bodily suffering was not the only trial to which this

fine spirit was subjected. The world heard no wail from

his lips; no appeal for sympathy ever came from his pen;

his high heart endured in silence; and, without a murmur of complaint, he died. Yet it is no secret now that for many years he had a

fierce struggle with poverty; enjoying no luxuries and few comforts; his

"means" derived from "daily toil for daily bread." A skeleton stood ever

beside his bed, mocking his "infinite jest and most excellent fancy:" converting into a succession of sobs those "flashes of merriment that were wont

to set the table in a roar." At the time when nearly every drawing-room, attic

and kitchen — when every class and order of society — was made merry and happy

by the brilliant fancies and genuine humour, of Thomas Hood, he was enduring

pain of body and anguish of mind. Nearly all his quaint conceits, his playful

sallies, and his sparks from words were given to the printer from the bed on which [135/136] he wrote, propped up by pillows; continually, continually, it was the same, up to the day that gave him freedom from the flesh.

Yet it was a genial and kindly spirit that dwelt in so frail a tenement of clay. Although his existence was a long disease rather than a life, he was singularly free from all cumbrance of bitterness and harshness. Feeling strongly for the sufferings of others, he was entirely unselfish, ever gracious, considerate, and kind. Though perpetually dealing with the burlesque, he never indulged in personal satire. We find no passage that could have injured a single living person. Never did his wit verge upon indelicacy; never did his facetious muse treat a solemn or sacred theme with levity or indifference.

In old Brandenburgh House there was once a bust of Comus; the pedestal, according to Lysons, bore this inscription: it comes in so aptly when writing of Hood, that I quote it: —

"Come, every muse, without restraint;

Let genius prompt and fancy paint;

Let wit and mirth, and friendly strife,

Chase the dull gloom that saddens life

True wit, that firm to virtue's cause,

Eespects religion and the laws;

True mirth, that cheerfulness supplies

To modest ears and decent eyes."

The world has, however, done justice to Thomas Hood; and he is not "deaf to the voice of the charmer." Reason, no less than Holy Writ, will tell us we plant that we may reap; that the knowledge of good or evil done is retained in a state after life; that death cannot destroy consciousness. We learn from the Divine Word that our works do follow us. Humanity is — and will be as long as men and women can read or hear — the debtor of Thomas Hood.

Why come not spirits from the realms of glory

To visit earth as in the days of old —

The times of ancient writ and sacred story?

Is heaven more distant 1 or has earth grown cold?

"To Bethlehem's air was their last anthem given,

When other stars before the One grew dim?

Was their last presence known in Peter's prison!

Or where exalting martyrs raised the hymn?"

Hood was born "a cockney," on the 23rd of May, 1799, in the Poultry, close to Bow Bells. His father dwelt there as one of the partners in a firm of publishers — Verner, Hood, and Sharpe. He was articled to his uncle, Mr. Eobert Sands, an engraver, and seems to have worked a while with the burin; but the specimens he has given us, however redolent of humour and rich in fancy, do not supply evidence that he would have excelled as an artist. It is obvious, indeed, that he did not "take" to the profession, for he deserted it early, and became a man of letters, finding his first employment in 1821, as a sort of-sub-editor of the London Magazine.

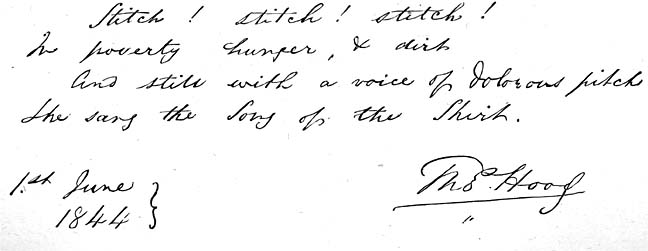

Manuscript in Hood's writing of "The Song of the Shirt" (in the original it is printed sideways on page 137).

"One who knew him in his childhood described him to me as a singular child — silent and retired — with much quiet humour, and apparently delicate health. I knew another friend of his youth, a Mr. Mason, a wood engraver, who told me much of the "earlier ways " of the boy-poet; that when a mere boy he was continually making shrewd and pointed remarks upon topics on which he was presumed to know nothing; that while he seemed a heedless listener, out would come some observation which showed he had taken in all that had been said ; and that, when a very child, he would often make some pertinent remark which excited either a smile or a laugh.

"He married, on the 5th of May, 1824, the sister of his "friend" Reynolds. It was a happy marriage, although both were poor; and it was "Love" who was "to light a fire in their kitchen." She was his companion, counsellor, and friend during the remainder of his troubled life — the comforter in whom he trusted; in mutual love and mutual faith realising, all through their weary pilgrimage, the picture drawn by another poet: —

"As unto the bow the cord is

So unto the man Is woman.

Though she bends him she obeys him;

Though she draws him, yet she follows;

Useless one without the other."

Left: Hood's Residence at Winchmore Hall. Right: Hood's Residence at Wanstead. Click on image for larger picture.

When first I knew them they resided in chambers, No. 2, Robert Street, Adelphi. While writing for the London Magazine, his labours must have been remunerative, for he removed from his "lodgings" in the Adelphi (where a child was born to him, who died in infancy), first to a pleasant cottage (then called "Eose Cottage") at Winchmore Hill (where his daughter Fanny — Mrs. Broderip — was born), and not long afterwards to a really large house at Wanstead — "Lake House" — with ample "grounds." He lost a considerable sum in some publishing speculation; and that loss early in his career was the cause of his subsequent embarrassment. At Lake House the younger "Tom" was born. It was originally the Banquet Hall of Wanstead House (Wellesley Pole's mansion), and there was a lake between [137/138] the two — now dwindled to a ditch. Both these dwelling-houses of the poet I have engraved.

His connection with the London Magazine led to intimacy with many of the finer spirits of his time, who appreciated the genius and loved the genial nature of the man. Foremost of those who exchanged warm friendship with him was Charles Lamb.

Owing mainly to his ill-health, he and his wife went but little into society; so, indeed, it was at all periods of their lives. Comparative solitude was, therefore, the lot of the poet. But the sacrifice implied little of self-denial. With wife, children, and friends, he could easily be made content; and, although no doubt fully appreciating praise, he never had much appetite for applause.

His long residence abroad — at Coblentz and Ostend — was, in a degree, compulsory. His publisher was a craving creditor — if, indeed, he ever was really a "creditor" at all, which I have reason to doubt. It was not without difficulty his return to England was effected in the year 1839. My intercourse with him was renewed in the small dwelling he occupied at Camberwell. He was there to be near [138/139] his kind friend, Dr. Eobert Elliot (brother of Dr. William Elliot, both of whom dearly loved the poet), "friend in need and a friend indeed."

It is in no degree necessary to my purpose to pass under review the works of Thomas Hood. They were very varied — novels, poems (serious as well as comic) filling seven volumes (exclusive of the two volumes of " Hood's Own"), collected by his daughter and his son. Nearly the whole of these were written, not only while haunted by pecuniary troubles, but while under the depressing influence of great bodily suffering, So it was with the merriest of his poems, " Miss Kilmansegg," composed (during brief intermissions of bodily pain which would have been accepted [139/140] by almost any other person as sufficient excuse for entire cessation from work; and, perhaps, might have been by him, but that it was absolutely necessary the day's toil should bring the day's food. Yet at this very time a sum of �50 was transmitted to him, without application, by the Literary Fund. Hood returned it, "hoping to get through his troubles as he had done heretofore." There was then a gleam of brightness in the long-darkened sky. In 1841 Theodore Hook died, and Hood became editor of the new Monthly Magazine. "Just then," as Mrs. Hood writes," poverty had come very near." He removed from Camberwell to 17, Elm-Tree Boad, St. John's Wood. He did not long keep his editorship, however: differences having arisen between him and Mr. Golburn, he was induced to start a magazine of his own.

Meanwhile, an accident, totally unanticipated, did that which years of labour had not done — made him famous. In the Christmas number of Punch, in 1843, appeared the "Song of a Shirt." It ran through the land like wildfire; was reprinted in every newspaper in the kingdom, although anonymous; and there was intense desire to know who was the author. He had been so long absent from the active exercise of his "calling," that when the poem burst upon world, there were many to whom the writer's name was "new."

In January, 1844, Hood's Magazine was issued. He laboured like a slave to give success to that speculation. It was in a melancholy sense "Hood's Own:" there was a "proprietor," but he was without " means;" there was an effort to do without a publisher; printer after printer was changed; the magazine was rarely "up to time," vexation brought on illness; he "fretted dreadfully; there was alarm as to the solvency of his co-proprietor, a man who had "lived too long in the world to be the slave of his conscience." Unhappy authors, who are their own publishers — lords of land in Utopia — will take warning by the fate of Thomas Hood and his "speculation" for his own behoof. It was a failure, and therefore his: had it been a success, no doubt it would have become the property of a publisher.

The number for June — the sixth number of Hood's Magazine — contained an announcement that on the 23rd of May he had been striving to continue a novel he had commenced; that on the 25th, "sitting up in bed, he tried to invent and sketch a few comic designs, but the effort exceeded his strength, and was followed by the wandering delirium of utter nervous exhaustion." Two of the "sick-room fancies" were published with the June number: the one is "Hood's Mag." — a magpie with a hawk's hood on; the other, "The Editor's Apologies," is a drawing of a plate of leeches, a blister, a cup of water-gruel, and three labelled vials; suggesting, according to some writing underneath, the sad thought by what harrassing efforts the food of mirth is furnished, and how often the pleasures of the many are obtained by the bitter suffering and mournful endurance of the ONE.

Yet three of the pleasantest letters he ever penned were written soon afterwards to the three children of his dear and constant friend, Dr. Elliot.

He rallied, however, sufficiently to resume work for his magazine, and many valued friends were willing and ready to help him — authors who were amply recompensed by the knowledge that they could thus serve the author of "The Song of a [140/141] Shirt." "I must die in Harness, like a Hero or a Horse," he writes to Bulwer Lytton on October 30th, 1844. Death was drawing nearer and nearer, but before its close approach there came a ray of sunshine to his death-bed — Sir Robert Peel granted to him a pension of �100 a year, or rather to his widow, for she was almost so. It was a small sum — a poor gift from his country in compensation for the work he had done; but it was very welcome, for it was the only boon he had ever received that was not payment for immediate toil — " toil hard and incessant" to the last. He was dying when the " glad tidings " came ; yet in the middle of November, 1844, he "pumped out a sheet of Christmas fun," and " drew some cuts " for his magazine. He was, as he said, "so near death's door, that he could almost fancy he heard the creaking of the hinges!" His friends were about him with small gifts of love: they came to give him "farewells;" and for all of them he had kind words and thoughts.

On the 3rd of May, 1845, he died, and on the 10th he was buried in the graveyard at Kensal Green.

Some seven years afterwards, subscriptions were raised, chiefly owing to the exertions of a kindred spirit, Eliza Cook (with whom the thought originated), and a monument was erected to his memory, designed and executed by the sculptor, Matthew Noble. On the 18th of July, 1854, it was unveiled in the presence of many of the poet's friends, Monckton Milnes (now Lord Houghton) "delivering an oration" over the grave that covered his remains. To raise that monument, peers and many men of mark contributed; but surely even higher honour was rendered to him — a yet purer and better homage to his memory — by the "poor needlewomen," whose offerings were a few pence, laid in reverence and affection upon the grave of their great advocate — a fellow-worker, whose toil had been as hard, as continuous, and as ill rewarded as their own.

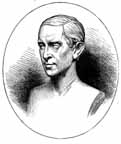

Thomas Hood. In the original publication this portrait appears centered above the title. Click on image for larger picture.

Thomas Hood. In the original publication this portrait appears centered above the title. Click on image for larger picture.

In person Hood was of middle height, slender and sickly-looking, of sallow complexion and plain features, quiet in expression, and very rarely excited, so as to give indication of either the pathos or the humour that must ever have been working in his soul. His was, indeed, a countenance rather of melancholy than of mirth : there was something calm, even to solemnity, in the upper portion of the face, seldom relieved, in society, by the eloquent play of the mouth, or the sparkle of an observant eye. In conversation he was by no means brilliant. When inclined to pun, which was not often, it seemed as if his wit was the issue of thought, and not an instinctive produce, such as I have noticed in other men who have thus become famous; who are admirable in crowds; whose animation is like that of the sounding-board, which makes a great noise at a small touch when listeners are many and applause is sure.

We have been so much in the habit of treating Tom Hood as a "joker," that we lose sight of the deep and touching pathos of his more serious poems. All are, indeed, acquainted with "The Song of a Shirt" and "The Bridge of Sighs," but throughout his many volumes there are poems of surpassing worth, full of the highest refinement — of sentiment the purest and the most chaste.

The house in which Hood died. Click on image for larger picture.

In writing a memoir of him in the "Book of Gems," for which, in consequence of his absence from England, I received no suggestions from himself, I took that view, and sometime afterwards I received from him a letter strongly expressive of [141/142] the gratification I had thus afforded him. His nature was, I believe, not to be a punster, perhaps not to be a wit. [Halls's note: Talfourd thus pictures him: — "Hood, so grave, andsad, that you were astonished to recognise in him the outpourer of a thousand wild fancies, the detector of the inmost springs of pathos, and the powerful vindicator of poverty and toil before the hearts of the prosperous."] The best things I have ever heard Hood say are those which he said when I was with him alone. I have never known him laugh heartily, either in society or in rhyme. The themes he selected for "talk" were usually of a grave and sombre cast; yet his playful fancy dealt with frivolities sometimes, and sometimes his imagination frolicked with nature in a way peculiarly his own. He was, however, generally cheerful, and often merry when in " the bosom of his family," and could, I am told, laugh heartily then; that when in reasonably good health, he was " as full of fun as a schoolboy." He loved children with all his heart; loved to gambol with them as if he were a child himself; to chat with them in a way they understood; and to tell them stories, drawn either from old sources, or invented for the occasion, such as they could comprehend and remember. [Hall's note: The son and daughter have preserved and printed some of these "impromptu" stories.] There was more than mere poetry in his verse —

"A blessing on their merry hearts,

Such readers I would choose,

Because they seldom criticise,

And never write reviews!" [142/143]

Literature was, as he expresses it, his "solace and comfort through the extremes of worldly trouble and sickness," "maintaining him in a cheerfulness, a perfect sunshine, of the mind." Well might he add, "My humble works have flowed from my heart as well as my head, and, whatever their errors, are such as I have been able to contemplate with composure when more than once the Destroyer assumed' almost a visible presence."

Poor fellow! He was longing to be away from earth when I saw him last; struggling to set free the

"Vital spark of heavenly flame;"

lying on his death-bed, watched and tended by his good and loving wife, who survived him only a few brief months: —

"She for a little tried To live without him — liked it not — and died!"

But he lived long enough to know that a pension had been settled upon her by Sir Robert Peel — a pension subsequently continued to his children. That comfort, that consolation, that blessing, came from his country to his bed of death!

Honoured be the name of Sir Robert Peel! great statesman and good man! It is not often that men such as he sit in highest places. Let Science, Art, and Letters consecrate his memory! It was he who whispered "peace" to Felicia Hemans, dying; bidding her have no care for those she loved and left on earth. It was he who enabled great Wordsworth to woo Nature undisturbed; he who lightened the drudgery of the desk to the Quaker poet, Bernard Barton; he who upheld the tottering steps, and made tranquility take the place of terror in the overtaxed brain of Robert Southey. From him came the sunshine in the shady place that was the home of James Montgomery. It was his hand that opened the sick-room shutters, and let in the light of hope and heaven to the death-bed of Thomas Hood.

Whether it be or be not true that Addison sent for his step-son, Lord Warwick, to his death-bed, "that he might see how a Christian could die," certain it is that the anecdote is often quoted as an encouragement and an example. We have, in the instance of Thomas Hood, such a case occurring under our immediate view, closing a life, not of glory and triumph, not of prosperity and reward, but of long-suffering in body and mind, of patient endurance, of humble confidence, of sure and certain hope, in the perfectness of holy faith. Ay, he was tried in the furnace of tribulation ; and his battle of life ended in according, while receiving, "Peace." [143/144]

These are the last lines he wrote: —

Farewell, Life! my senses swim,

And the world is growing' dim;

Thronging shadows cloud the light,

lake the advent of the night, —

Colder, colder, colder still,

Upward steals a vapour chill;

Strong the earthly odour grows, —

I smell the mould above the Rose!

"Welcome, Life! the spirit strives,

Strength returns and hope revives;

Cloudy fears and shapes fornlorn

Fly like shadows of the morn —

O'er the earth there comes a bloom, —

Sunny light for sullen gloom,

Warm perfume for vapours cold, —

I smell the Eose above the mould:"

In one of the letters I received about this time from his true and faithful and constant friend, F. O. Ward, he writes to me: — "He saw the on-coming of death with great cheerfulness, though without anything approaching to levity; and last night, when his friends, Harvey and another, came, he bade them come up, had wine brought, and made us all drink a glass with him, 'that he might know us for friends, as of old, and not undertakers.' He conversed for about an hour in his old playful way, with now and then a word or two full of deep and tender feeling. When I left he bade me good-bye, and kissed me, shedding tears, and saying that perhaps we never should meet again."

I have his own copy of the last letter he ever wrote : it is to Sir Robert Peel: —

"DEAR SIR, — "We are not to meet in the flesh. Given over "by physicians and by myself, in this extremity I feel a comfort for -which I cannot refrain from again thanking you with all the sincerity of a dying man, at the same time bidding you a respectful farewell.

"Thank God, my mind is composed, and my reason undisturbed; but my race as an author is run. My physical debility finds no tonic virtue in a steel pen, otherwise I would have written one more paper — a forewarning against an evil, or the danger of it, arising from a literary movement in which I have had some share; a one-sided humanity, opposite to that catholic, Shakspearian sympathy which felt with king as well as peasant, duly estimating the moral temptations of both stations. Certain classes at the poles of society are already too far asunder. It should he the duty of our writers to draw them together by kindly attraction — not to aggravate the existing repulsion, and place a wider moral gulf between rich and poor — hate on the one side, and fear on the other. But I am too weak for this task — the last I had set myself. It is death that stops my pen, you see, and not my pension. God bless you, sir, and prosper all your measures for the benefit of my beloved country!"

Almost his latest act was to obtain some proofs of his portrait, recently engraved, and to send one to each of his most esteemed friends, marked by some line of affectionate reminiscence. The one he sent to us I have engraved at the head of this memory.

.His daughter writes me thus of his last hour on earth: — " Those who lectured him on his merry sallies and innocent gaiety should have been present at his deathbed, to see how the gentlest and most loving heart in the world could die!" " Thinking himself dying, he called us round him — my mother, my little brother, and myself — to receive his last kiss and blessing, tenderly and fondly given; and gently clasping my mother's hand, he said, Remember, Jane, I forgive all — all! He lay for, some time calmly and quietly, but breathing painfully and slowly; and my mother, [144/145] bending over him, heard him murmur faintly,' O Lord, say, Arise, take up thy cross and follow Me!'"

The Tomb of Thomas Hood. Click on image for larger picture.

He died at Devonshire Lodge, in the New Finchley Boad. Of that house we procured a drawing, and have engraved it.

He left one son and one daughter.

Genius is not often hereditary. There are but few immortal names, the glory of which has been "continued." It is gratifying to know that the seed planted by Thomas Hood and" his estimable wife has borne fruit in due season. The daughter (Fanny) wedded a good clergyman in Somersetshire, and, though now a widow, is the happy mother of children (one of whom, by the way, is our god-daughter) : she is the author of many valuable works, the greater number of them being specially designed for the young. The name of "Fanny Broderip " is honoured in letters. To the son — another " Tom " — it is needless to refer. He has added renown to the venerated name he bears, and has written much that his great father himself might have owned with pride. They have had. a sacred trust committed to them, and so far have nobly redeemed it. [145/146]

Alas! since this Memory was first published, the son, "Tom Hood the younger," has also been called from earth, dying in the prime of life.

Tom much resembled the father in mind; he was gently genial — if the term may pass. His wit also was calm, not loud: it was not of the character that can set the table in a roar. He had, I believe, a stern struggle with life — a wrestle, indeed, in which he was worsted. I knew but little of him towards the close of his somewhat brief career; he seemed absorbed by requisite labour to satisfy present and, it may be, pressing, needs, and did not give himself the fair play that might have led to a far higher position than he was destined to occupy. Tom had one advantage which his father had not: his personal appearance was much in his favour. He was handsome: the outline of his face was singularly fine; the features were regular, and the expression indicated the kindly nature of the man ; while his form was tall, straight, and not without natural grace.

In this Memory of Thomas Hood I have printed his last letter, and quoted his latest words. They are such as must, in the estimation of all readers, raise him even higher than he yet stands. The world owes him much; Humanity is his debtor; and who will not exclaim, borrowing from another poet —

"The thoughts of gratitude shall fall like dew

Upon thy grave, good creature!"

References

Hall, S. C. A Book of Memories of Great Men and Women of the Age, from Personal Acquaintance. 3rd ed. London: J. S. Virtue, [1871].

Last modified 25 March 2005