The following paragraphs come from the Introduction to Literary Appropriations of Myth and Legend in the poetry of Alfred Lord Tennyson, William Morris, Algernon Charles Swinburne and William Butler Yeats, by Ewa Młynarczyk (1982-2022). See bibliography for details. This was written as a doctoral thesis for the Institute of English Studies, University of Warsaw, but, very sadly, Ewa died before she was able to defend it. Her supervisor, Professor Grażyna Bystydzieńska, having given it a final edit, the institute has now made it available as a book. The proceeds of the paperback edition will – in accordance with the wish of Ewa's parents – support the Avalon Foundation in Warsaw, which helps people with disabilities. A free electronic version can also be downloaded (click on the title in the bibliography). — Links and illustration added, and footnotes incorporated, by JB

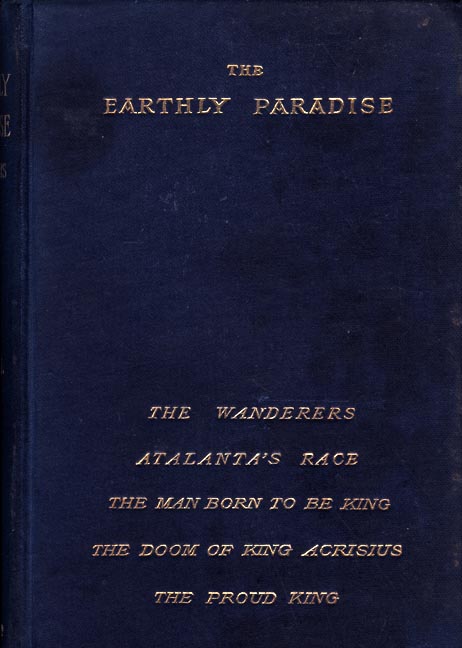

illiam Morris’s sympathies clearly lay with medieval times. In fact, he may be considered as one of the most prominent representatives of a cultural phenomenon known as Victorian medievalism. His interest in the Middle Ages manifested itself as early as his first literary endeavours of 1856 when he published his short stories in the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, as well as in his first volume of poetry, The Defence of Guenevere and Other Poems (1858). Yet, it was in his most popular work of his times, The Earthly Paradise (1868-1870), that Morris's fascination with legend and mythology found its fullest expression: after the publication of the work, he came to be known as "The William Morris, Author of The Earthly Paradise (cf. Maurer 247, n.2). A similar great popularity was only achieved by Tennyson’s In Memoriam and John Keble’s The Christian Year.

This four-volume work may be described as a year of storytelling, as it is neatly divided into twelve months, each including two tales — one taken from classical mythology and the other being a medieval legend. Such a diversity of stories has been accounted for in the introductory tale “Prologue: The Wanderers,” where it is reflected in the cultural backgrounds of its three main protagonists, Rolf of Greek and Norse origin, who was born in Byzantium and later travelled to his father’s origin, native Norway, Nicholas, a Breton squire, and Laurence, a Swabian priest and alchemist in search of the philosopher’s stone. The three companions were united by their great love of old lore, and in particular, tales of the fabulous Earthly Paradise, a world immune to aging and death....

While the retellings of the classical tales may at times sound somewhat lifeless, The Earthly Paradise is noteworthy for its tales based on medieval northern themes. One such example is “The Lovers of Gudrun,” the medieval tale for November, which marks one of Morris’s most successful attempts at recasting an Old Norse saga directly from its Icelandic sources, the tale which Morris himself considered his best piece of the whole third volume: he described “The Lovers of Gudrun” to Charles Eliot Norton as “the best thing I have done” (Letters I: 98); and, again, in a letter to Algernon Charles Swinburne of the same date, thanks the other poet for his critical remarks about the third part of The Earthly Paradise and observes, “I am rather painfully conscious myself that the book would have done me more credit if there had been nothing in it but the Gudrun” (Letters 1: 100)....

Morris was not the first nineteenth-century English writer to make use of Old Norse legends. The revival of interest in the ancient poetry of the North was part of a larger European phenomenon of the late eighteenth century which aimed to help shape national identities through the study of the origins of local languages and cultures. As explained by Heather O’Donogue (on whose work this discussion is mainly based):

Old Norse texts were presented as a significant and valuable alternative to the body of Greek and Roman literature, a status backed up by ideas which were beginning to circulate about the early Germanic languages being on a par with Latin and Greek as equal Indo-European descendants from Sanskrit. In Britain, Old Norse-Icelandic texts could provide information about the early history of England and Scotland, and insights into the culture and mentalité of ancestral nations. [110]....

[Yet] "no other English poet,” writes Charles Harold Herford, “has felt so keenly the power of Norse myth; none has done so much to restore its terrible beauty, its heroism, its earth-shaking humour, and its heights of tragic passion and pathos, to a place in our memories, and a home in our hearts” (75). Morris’s lifetime fascination with the Old North, its medieval literature and culture led to the publication of over fifty pieces in prose and verse, stylised or directly based on Old Norse literature” (for a full list of these works see Litzenberg 93-105)....

It may be posited that myths and legends served as sources of inspiration for Morris’s central literary works. The tales of The Earthly Paradise gave a respite from the ugly reality of Industrial England and Morris's easy manner of storytelling met with enthusiastic responses from his Victorian readers. Yet, contrary to the opinions of some critics, this interest in myth and legend was not merely driven by Morris’s escapism. His in-depth study of medieval literature of the North gave shape to Morris’s ideas about the perfect society of the future, while the immense work he put in the retellings and translations of Old Norse sagas helped to introduce Icelandic literature to a wider audience. Moreover, as Dinah Birch rightly observes, even though Morris was not directly involved with the scholarly comparative studies of myth which developed in his times, the comprehensive approach to myth and legend which he shows in the compilation of the tales in The Earthly Paradise, encompassing stories of various cultural backgrounds, in a way makes him a comparative mythologist, too: “His syncretic thought enabled him to blur the edges of differing bodies of myth: classical, Icelandic, Christian — taking what he needed and making it his own” (10). She also points out that what Morris found of particular interest in myth was its timeless, ahistorical nature, its roots in the popular folk tales, which excluded a single authorship, and the element of the sacred wisdom, which was not restricted by Christian dogma, the features which had also been important to the Romantic poets (6). Interestingly, a similar view of myth and legend as both a folk story of the people and a repository of sacred images was what also attracted Morris’s one-time follower, William Butler Yeats. [Młynarczyk 36-43]

Links ti Related Materialk

- Myths and Legends in Victorian Literature (an excerpt from the Preface)

- George Eliot's Casaubon, the Scholar-Mythologist (an excerpt from the Introduction)

Bibliography

Birch, Dinah. “Morris and Myth: A Romantic Heritage.” Journal of William Morris Studies 7/1 (1986): 5-11.

Herford, Charles Harold. Norse Myth in English Poetry. Manchester: Longmans, Green and Co., 1919.

Litzenberg, Karl. “William Morris and Scandinavian Literature: A Bibliographical Essay.” Scandinavian Studies and Notes 13 (1933): 93-105.

Maurer, Oscar, Jr. “William Morris and the Poetry of Escape.” In Nineteenth Century Studies. Edited by Herbert Davis, William C. DeVane, and Robert Cecil Bald. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1940. 247-276.

Młynarczyk, Ewa. hereLiterary Appropriations of Myth and Legend in the poetry of Alfred Lord Tennyson, William Morris, Algernon Charles Swinburne and William Butler Yeats. Warsaw: Institute of English Studies, University of Warsaw, 2024.

Morris, William. The Collected Letters of William Morris. Edited by Norman Kelvin. 4 vols. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984-96.

____. The Earthly Paradise. Edited by Florence Saunders Boos. 2 vols. New York, London: Routledge, 2002.

O'Donoghue, Heather. Old Norse-Icelandic Literature. A Short Introduction. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishing, 2004.

Last modified 19 January 2004