"I realise how how insignificant death is, when I see how vitally alive that dead man is, how much I admire him, listen to his words, try to understand and obey him, more than any other man alive." Proust wrote these words (in French) to his English friend Marie Nordlinger in Manchester shortly after learning of Ruskin's death. And in an obituary article, he concluded: "Dead, [Ruskin] continues to enlighten us, like those dead stars whose light reaches us still, and one may say of him what he said on the occasion of Turner's death: 'Through those eyes, now filled with dust, generations yet unborn will learn to behold the light of nature'."

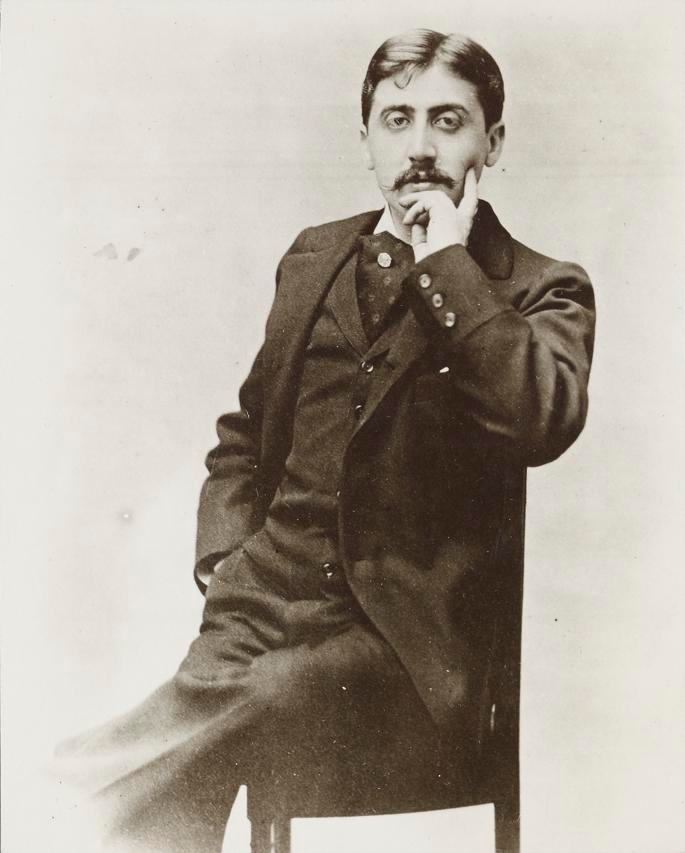

Photo of Marcel Proust in 1895, by Otto Wegener.

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

When Ruskin died, aged 80, on 20 January 1900, Proust was only 28 years old, a virtually unknown writer with a reputation as a social butterfly, still relying on pocket money from his father, the renowned epidemiologist Dr Adrien Proust. He had published his first book Les Plaisirs et les jours in June 1896, preceded by a few short articles with limited circulation. There is no evidence that Ruskin knew of Proust’s existence, let alone any of his writing. We can safely say that Ruskin died without knowing anything about Proust. Yet it was Ruskin’s very death which goaded Proust to work seriously.

The discovery: a first catalyst

Autumn 1899 marked a turning point in Proust’s life. After spending several weeks, without his parents, in the fashionable spa town of Évian-les-Bains on the south side of Lake Geneva, in the company of aristocratic friends, Proust wrote a letter to his mother asking her to send him, urgently, Robert de La Sizeranne's Ruskin et la religion de la beauté that had been published in 1897. Why? Because he wanted "to see the mountains through the eyes of that great man [Ruskin]," through La Sizeranne's sensitive translations of passages of Ruskin. Proust was in a part of France dear to Ruskin, among the majestic Alps, that the 14-year-old boy had first seen from Schaffhausen in Northern Switzerland in 1833, and recalled in a passage in Praeterita, sensitively translated by La Sizeranne:

suddenly – behold – beyond! There was no thought in any of us for a moment of their being clouds. They were as clear as crystal, sharp on the pure horizon sky, and already tinged with rose by the sinking sun. [...] with so much of science mixed with feeling as to make the sight of the Alps not only the revelation of the beauty of the earth, but the opening of the first page of its volume, – I went down that evening from the garden-terrace of Schaffhausen with my destiny fixed in all of it that was to be sacred and useful. [35. 115-115]

Proust did not wait for the book to arrive but returned in haste to Paris where he discovered more of Ruskin in the Bibliothèque nationale – a translation into French, by Olivier Georges Destrée, of "The Lamp of Memory," chapter 6 of The Seven Lamps of Architecture. This episode was transposed in Proust's novel, when, in the library of the Guermantes' Paris residence, the Narrator realises that his vocation is that of a writer and that the content of his proposed work is already within himself, he simply has to begin to write and translate it: "I realised [...] that the essential, the only true book, though in the ordinary sense of the word it does not have to be 'invented' by a great writer – for it exists already in each one of us – has to be translated by him. The function and the task of a writer are those of a translator."

The chapter that Proust was reading, in French, opens with a lyrical description of a landscape, in the French Jura, within proximity of places he had explored during his Évian stay. La Sizeranne too had also translated this opening paragraph and included it in Ruskin et la religion de la beauté as a fine example of Ruskin as a seer and painter in words, even comparing this text to Monet's technique of painting the Haystacks: "he paints what he sees", adding, "Ruskin would not add a blade of grass he had not seen, or before which he had not stood in rapture." In this passage from "The Lamp of Memory," there is also a striking similarity between Ruskin in French translation and Proust's own style at the beginning of Combray:

It was spring time, too; and all were coming forth in clusters crowded for very love; there was room enough for all, but they crushed their leaves into all manner of strange shapes only to be nearer each other. There was the wood anemone, star after star, closing every now and then into nebulae; and there was the oxalis, troop by troop, like virginal processions of the Mois de Marie, the dark vertical clefts in the limestone choked up with them as with heavy snow, and touched with ivy on the edges – ivy as light and lovely as the vine; and, ever and anon, a blue gush of violets, and cowslip bells in sunny places; and in the more open ground, the vetch, and comfrey, and mezereon, and the small sapphire buds of the Polygala Alpina, and the wild strawberry, just a blossom or two, all showered amidst the golden softness of deep, warm, amber-coloured moss. [8. 222-223]

Jonathan Wylder's statue of Robert Grosvenor,

photographed by Beata May. Source:

Wikimedia Commons.

As Proust delved further into the chapter, more themes of memory and time emerged, the very essence of In Search of Lost Time. One of these is Ruskin's belief that architecture preserves or memorialises the past: "We may live without her [architecture], and worship without her, but we cannot remember without her" (8. 224). Likewise his plea for the preservation of buildings, rather than their destruction. On his late twentieth-century statue of Robert Grosvenor, 1st Marquess of Westminster, located at the corner of Wilton and Grosvenor Crescents, Belgravia, London, UK, the sculptor Jonathan Wylder has affixed the following Ruskin quotation from "The Lamp of Memory": "When we build, let us think [that] we build for ever" (8. 233).

A second catalyst

Ruskin's death, a few weeks after this discovery, was a second catalyst for Proust. Proust felt and believed that Ruskin's soul had transmigrated to him, and that he had a duty of care, a duty to obey, and a duty to transmit Ruskin's voice. It was a huge responsibility. Surely such a sentiment is unique in the world of literature? Ruskin was now Proust's supreme spiritual and aesthetic guide in crucial aspects of his life – in art and architecture and in providing a philosophy of life that placed work and sacrifice at the forefront. Proust regained strength and focus, and, with a sustained burst of energy, paid homage to his "maître à penser" in multiple, overlapping ways – by reading and learning by heart nearly all of Ruskin's works (so he claimed!), by writing obituary articles (Proust was the first French person to do so), by completing the enormous task of translating into French The Bible of Amiens and Sesame and Lilies. He made pilgrimages in the steps of Ruskin to Gothic cathedrals and churches in Rouen, Amiens, Chartres, Laon, Beauvais, Caen, Lisieux, Évreux and Venice. He travelled in Burgundy to Avallon and Dijon with Ruskin in pursuit of Ruskin's spirit, seeing architecture through his eyes and absorbing it to use in his novel, the structure of which, Proust maintained, was a cathedral.

Ruskin's watercolour of the Palazzo

Contarini-Fasan, Venice, 1841.

Proust was intoxicated by Ruskin, to such an extent that when he thought his own death was imminent in 1900 (he was wrong about this!), his overwhelming desire was not only to see Venice through Ruskin’s eyes but to be able "before dying to approach, touch, and see incarnated in decaying but still-erect and rosy palaces, Ruskin’s ideas on domestic architecture of the Middle Ages." He absorbed Carpaccio's paintings of the St Ursula cycle, and the Palazzo Contarini Fasan with its traceried parapet; he read aloud passages from St Mark's Rest in the eponymous Basilica, and translated The Bible of Amiens. From Venice, he made a day trip to Padua to see the faded Giotto frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel, and the Virtues and Vices around the walls, in particular the figure of Carità / Charity that Ruskin described in The Stones of Venice. All of these elements are transposed into Proust's novel in which Venice has a central role. Proust felt that Ruskin held the key or sesame to the universe, a powerful reason for wanting to understand and penetrate his thought.

"Work while you have light" was the key message in Ruskin’s preface to the 1871 edition of Sesame and Lilies (18. 37). This was the message that Proust called an "evangelical sermon" in his letter to Georges de Lauris, exhorting him at all times to keep Ruskin’s words before his eyes. Ruskin taught Proust how to work and how to see, and Proust was a willing student: "I had said to myself, in my enthusiasm for Ruskin: He will teach me, for he too, in some portion at least, is he not the truth? He will make my spirit enter where it had no access, for he is the door. He will purify me, for his inspiration is like the lily of the valley. He will intoxicate me and will give me life, for he is the vine and the life.""

Concomitant with work was sacrifice, indeed one of the seven lamps of architecture in the book of the same name that was seminal reading for Proust. Both Ruskin and Proust sacrificed their lives for their work. Proust's last weeks were particularly painful during which he refused medical treatment, food and heating; his only goal was to finish his novel, nothing else mattered.

Ruskin's writings were instrumental in transforming the Parisian dilettante into the greatest French writer of the twentieth century. Ruskin sustained Proust through the deaths of his parents (in 1903 and 1905) and friends, and during the horrors of World War I when he was confined to Paris. Proust died on 18 November 1922, at the age of 51, in a sparsely furnished, cold, rented room at number 44, rue Hamelin.

Related Material

Further reading

Batchelor, John. John Ruskin: No Wealth But Life. London: Pimlico, 2001.

Brownell, Robert. Marriage of Inconvenience. London: Pallas Athene, 2013.

Carter, William C. Marcel Proust: A Life. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013.

Gamble, Cynthia. Proust as Interpreter of Ruskin: The Seven Lamps of Translation. Birmingham, Alabama: Summa, 2002.

Gamble, Cynthia. Voix entrelacées de Proust et de Ruskin. Paris: Classiques Garnier, 2021. [Review.]

Gamble, Cynthia and Matthieu Pinette. L'œil de Ruskin. L'exemple de la Bourgogne. Dijon: Les Presses du réel, 2011.

Hilton, Tim. John Ruskin: The Early Years 1819-1859. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000.

Hilton, Tim. John Ruskin: The Later Years. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000.

Proust, Marcel. The Cambridge Companion to Proust. Ed. by Richard Bales. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Proust, Marcel. In Search of Lost Time. Ed. by Christopher Prendergast. 6 vols. London: Penguin Classics, 2003.

Ruskin, John. Works. Ed. by E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. The Library Edition. 39 vols. London: George Allen, 1903-1912.

Ruskin, John. Praeterita. Ed. by Francis O'Gorman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Ruskin, John. The Cambridge Companion to John Ruskin. Ed. by Francis O'Gorman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Tadié, Jean-Yves. Marcel Proust: Biographie. Paris: Gallimard, 1996.

Tadié, Jean-Yves, Marcel Proust: A Biography. Translated by Euan Cameron. London: Viking, 2000.

Watt, Adam. Marcel Proust. London: Reaktion Books, 2013.

Further listening

I highly recommend the reading and interpretation of Proust's novel by Neville Jason. This unabridged recording runs to 150 hours. It is a remarkable feat and brings the novel to life in all its complexity, with its humour, wit and mystery.

Proust, Marcel. Remembrance of Things Past. 120 CDs, in 7 sets/boxes. London: Naxos AudioBooks, 2012.

Created 5 August 2021