[The decorative initial "T" incorporates Thomas Woolner's medallion portrait of Tennyson. GPL]

ennyson’s poetry was interpreted by a number of visual artists and his subjects were presented as paintings on canvas and in the form of illustrations. The most celebrated book was the edition published by Edward Moxon in 1857; usually known as the ‘Moxon Tennyson’, it contained wood-engravings by Dante Rossetti, J.E. Millais, and William Holman Hunt. On no other occasion were all three of the founding members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood brought together to embellish a single text, and Moxon’s anthology is widely regarded as a work of crucial importance.

ennyson’s poetry was interpreted by a number of visual artists and his subjects were presented as paintings on canvas and in the form of illustrations. The most celebrated book was the edition published by Edward Moxon in 1857; usually known as the ‘Moxon Tennyson’, it contained wood-engravings by Dante Rossetti, J.E. Millais, and William Holman Hunt. On no other occasion were all three of the founding members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood brought together to embellish a single text, and Moxon’s anthology is widely regarded as a work of crucial importance.

Tennyson was revered by the Brothers and had a significant impact on the development of Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics. The Brotherhood’s focus on psychological drama combined with medievalism and ‘truth to nature’ were key elements in Tennyson’s verse, and the poet was often described as a practitioner of Pre-Raphaelitism before the event. Tennyson acknowledged the link and although a number of established artists provided the majority of the illustrations, he wanted the Pre-Raphaelites to be given the opportunity to explore the consonance between styles. On his insistence, Moxon signed them up.

Yet the poet’s response to the completed work was far from an ringing endorsement. Although he recognized the compatibility between the Pre-Raphaelites’ imagery and the tenor of his poems, he was baffled by the extent to which they had used the verse as an opportunity to make their own, idiosyncratic readings. As far as the Pre-Raphaelites were concerned, his verse was just an imaginative starting point, a hint from which they proceeded to create a new, visual text which was not always obviously linked to the source material; for the poet, on the other hand, the illustrator’s task was entirely a matter of visualizing the writer’s ideas, and not his own. His bewilderment is preserved in a conversation with William Holman Hunt, in which he quizzes the artist as to why he deployed an interpretive approach.

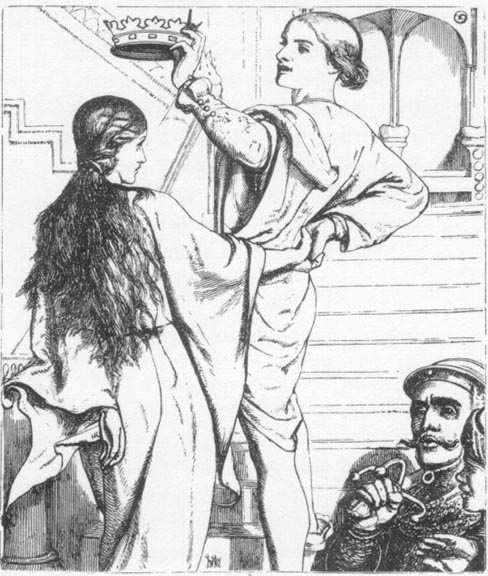

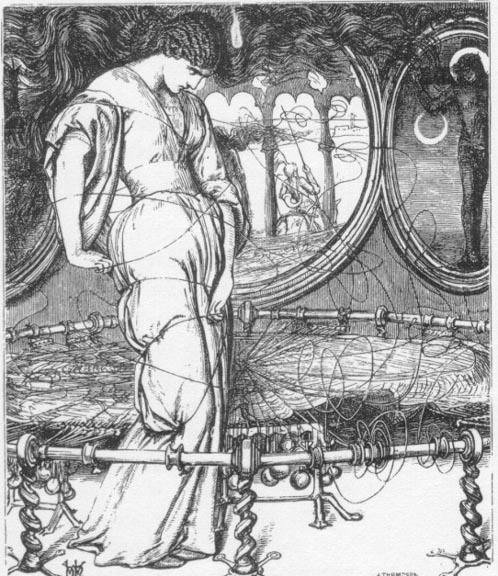

Left: The Beggar Maid. Right: The Lady of Shalott. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Tennyson’s contribution embodies the orthodox early-Victorian belief in the artist as the author’s servant, while Hunt outlines the new ethos of the middle of the century, which highlights the illustrator as a creator in his own right. Their focus is on the visual treatment of ‘The Lady of Shalott’ and ‘The Beggar Maid’, and how they could or should have been illustrated. Tennyson opens the conversation, noting how he ‘was always interested in your paintings, and lately your illustrations to my poems, which strongly engaged my attention!’ After some general talk he said, “I must now ask you why did you make the Lady of Shalott, in the illustration, with her hair wildly tossed about as if by a tornado?”’ The painter tells us that he found himself ‘rather perplexed’ by the poet’s query and tried to explain his reason for depicting the lady that way.

I replied that I had wished to convey the idea of her threatened fatality by reversing the ordinary peace of the room and of the lady herself; that while she recognised that the moment of her catastrophe had come, the spectator might also understand it.

‘But I didn’t say that her hair was blown about like this. The there is another question … Why did you make the web wind around and round her like the threads of a cocoon?’

Now, I exclaimed, ‘surely that may be justified, for you say –

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack’d from side to side;

a mark of the dire calamity that had come upon her.’

But Tennyson broke in with, ‘But I did not say it floated round and round her.’ My defence was, ‘May I not urge that I have only half a page on which to convey the impression of weird fate, whereas you use about fifteen pages to give expression to the complete idea?’ But Tennyson laid it down that ‘an illustrator ought never to add anything to what he finds in the text.’ The leaving the question of the fated lady, he persisted. ‘Why did you make Copetua leading the beggar maid up a flight of steps?’

‘Don’t you say –

In robe and crown

The King stepped down,

To meet and greet her

On her way.

Does not the old ballad originally giving the story say something clearly to this effect? If so, I claim double warrant for my interpretation. I feel that you do not enough allow for the difference of requirements in our two arts. In mine it is needful to trace the end from the beginning in one representation. You can dispense with such a licence. In both arts it is essential that the meaning should appear both clear and strong. Am I not right?’

‘Yes’, he said, ‘but I think the illustrator should always adhere to the words of the poet!’

‘Ah, if so, I am afraid I was not a suitable designer for the book’ [Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood 2: 124–25]

Works Cited

Holman Hunt, William. Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. 2 Vols. London: Macmillan, 1905.

Tennyson, Alfred. Poems. London: Moxon, 1857.

Last modified Created 17 May 2015