HE WISHES FOR THE CLOTHS OF HEAVEN

Had I the heavens' embroidered cloths,

Enwrought with golden and silver light,

The blue and the dim and the dark cloths

Of night and light and the half light,

I would spread the cloths under your feet:

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

In the lyrical opening lines of "He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven," W. B. Yeats exalts his own love and his beloved alike, by expressing his longing to woo her with ethereal riches, glowing with the changing colours of the over-arching skies. The imagery is vast in its connotations, veering between different kinds of splendour, from the brightness of day to the plush, velvety tones of night. The poet then abases himself by admitting the reality: that he only has his dreams to offer. He seems to have come down to earth. But his estimation of his love has not changed, and nor has his view of the woman he loves. His love (the main preoccupation here) remains deep and intense, for he puts these fragile dreams completely at the woman's disposal, to "tread on" gently if she cares for him. Here is romantic longing figuratively clothed in fine words, and expressing itself in a fine gesture. His request in the last line carries the equally romantic implication of possible pain.

Th poem appears in W. B. Yeats's The Wanderings of Oisin and Other Poems, which was published in 1889.The volume as a whole brought together from this decade Yeats's youthful verse, often with a fin de siècle preoccupation with hopeless love, and a yearning for death. The two preoccupations were fused in "He Wishes His Beloved Were Dead":

Were you but lying cold and dead,

And lights were paling out of the West,

You would come hither, and bend your head,

And I would lay my head on your breast;

And you would murmur tender words,

Forgiving me, because you were dead....

Nothing could better encapsulate the fin de siècle mood of the late 80s and 90s. But "He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven" belongs here just as much, except insofar as, like "The Lake Isle of Innisfree," it was destined to outlive its era and capture the imagination of future generations. It also contains the seeds of his future development as a poet.

Yeats in the nineties

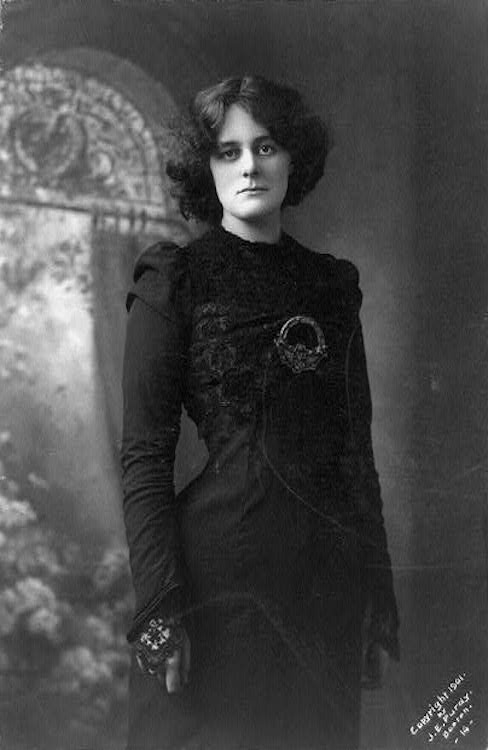

Maud Gonne, c. 1901.

Library of Congress,

Washington (repro. no. LC-DIG-ds-14057).

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

The nineties were a momentous decade for Yeats in every way, not only in his romantic and writing life, but also in his ideological development. In 1891, Maud Gonne, whom he had met in 1889, rejected his marriage proposal, something he perhaps feared when writing, "He Wishes He Had the Cloths of Heaven." In between these two important life events, he had confirmed his occult interests by joining the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in 1890. In the following year, he helped to found the Rhymers' Club in London, and followed this up by founding the Irish Literary Society in London as well. After this, in 1892, came the founding of the Irish Literary Society in Dublin. In this year too he published The Countess Cathleen and Various Legends and Lyrics. His writing output at this time was prodigious. The next milestone was the production of his play The Land of Heart's Desire in London in 1894. Then a collection of his poems came out in 1895.

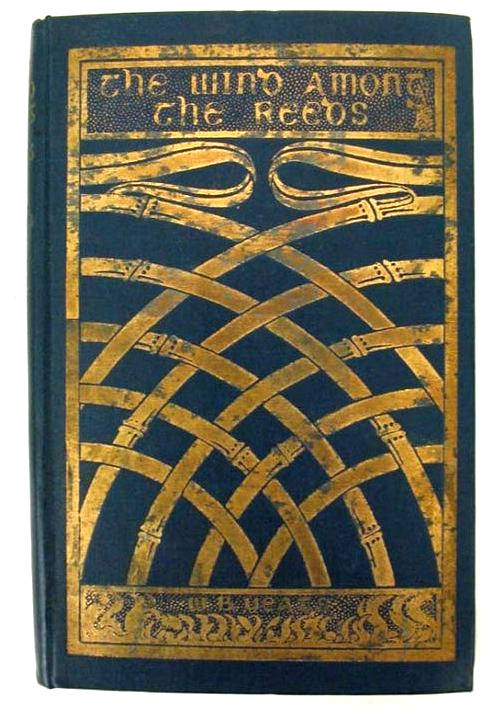

In 1896 he met two people who, like Maud Gonne, would have a huge influence on him — the widowed Lady Gregory, with her wonderful estate at Coole Park in Galway, who would support and advise him, and nurture his dreams of an Irish literary Renaissance; and the Irish dramatist, J. M. Synge, who would turn him towards unflinchingly direct speech in his dialogues. Another source of inspiration found its outlet a year later, when he published The Secret Rose, a collection of his stories of the occult — often with Irish folklore elements. In 1897 too he helped found the Irish Literary Theatre, its manifesto drawn up in his own handwriting (see Foster 184). And in 1899 its inaugural plays, including Yeats's own The Countess Cathleen, were staged, and Yeats's new collection of poems, The Wind among the Reeds, was published.

Bindings designed for the early books by Yeats's friend, Althea Gyles. Left to right: (a) Poems (1895). (b) TThe Secret Rose (1897). (c) The Wind among the Reeds (1899). Click on the images to enlarge them and for more information.

Yeats in the early twentieth century

Having been operating in the larger world and coming under diverse influences, Yeats emerged from those packed years with a growing reputation, a changing approach to poetry, and a wider vision, encompassing nationalist concerns at one extreme, and esoteric forays at the other. There was already a glimpse of this turn from enchantment in the way he relinquished "the heavens' embroidered cloths" in "He Wishes He Had the Cloths of Heaven," but it developed further and is much more keenly felt in a later poem entitled "The Cold Heaven." This poem's date of composition is unknown, but it was eventually published in Responsibilities in 1914.

Suddenly I saw the cold and rook-delighting heaven

That seemed as though ice burned and was but the more ice,

And thereupon imagination and heart were driven

So wild that every casual thought of that and this

Vanished, and left but memories, that should be out of season

With the hot blood of youth, of love crossed long ago;

And I took all the blame out of all sense and reason,

Until I cried and trembled and rocked to and fro,

Riddled with light. Ah! when the ghost begins to quicken,

Confusion of the death-bed over, is it sent

Out naked on the roads, as the books say, and stricken

By the injustice of the skies for punishment?

Roy Foster's analysis of this brings out the changes now taking place in his approach:

In relation to Yeats's artistic problems, "The Cold Heaven" is the most significant poem in the book and points the way to his later development. The heaven which he now sees in vision is not that which he had imagined in the 'nineties, a pretty heaven of "embroidered cloths," but a cruel and remorseless one of burning ice; for a staggering instant he beholds himself shorn of all his accomplishments and defences, with no memory left except that all-important one of love crossed long ago, for which he feels inexplicably compelled to take all the blame. The poem ends in terror.... the question at the end forces itself out like an exclamation; instead of reluctantly admiring the poet's facility, we are swept into the poem, and find his reaction dramatically possible and meaningful for ourselves. "We sing amid our uncertainty," Yeats wrote in Per Amica Silentia Lunae [an exploration of the self, divided between the natural and supernatural worlds, in 1917]. Much uncertainty can be found in "The Cold Heaven."

There is less uncertainty in the short poem, "A Coat," the last in Responsibilities apart from the epilogue. It was, in fact, the poem with which he had originally intended to close the volume (see Foster 521):

I made my song a coat

Covered with embroideries

Out of old mythologies

From heel to throat;

But the fools caught it,

Wore it in the world’s eyes

As though they’d wrought it.

Song, let them take it

For there’s more enterprise

In walking naked.

With its reference to "embroideries," this seems to refer directly to "He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven," and, interestingly, gives one important reason for moving on from it: facile imitation by others. "The fools caught it/ As though they'd wrought it." This perhaps implies regret, even bitterness. Even if it meant exposing his vulnerabilities to the world, Yeats now wanted to make his own original, inimitable mark.

The later poetry

And so, indeed, he did. There is no uncertainty in one of his very last poems, written only a year before he died at the age of 74. Moreover, despite the fact that he was now facing his own mortality, there is more sense of agency. He is not shrugging off the "embroideries" but actually in amongst the tatters of his own innermost feelings. In this poem, "The Circus Animals' Desertion," published posthumously in the Last Poems of 1940, he looks back in more detail at his earlier work, again seeing himself as having been distracted and absorbed by the surface of things, and to have employed poetic artifice to showcase it:

I sought a theme and sought for it in vain,

I sought it daily for six weeks or so.

Maybe at last being but a broken man

I must be satisfied with my heart, although

Winter and summer till old age began

My circus animals were all on show,

Those stilted boys, that burnished chariot,

Lion and woman and the Lord knows what.

II

What can I but enumerate old themes,

First that sea-rider Oisin led by the nose

Through three enchanted islands, allegorical dreams,

Vain gaiety, vain battle, vain repose,

Themes of the embittered heart, or so it seems,

That might adorn old songs or courtly shows;

But what cared I that set him on to ride,

I, starved for the bosom of his fairy bride.

And then a counter-truth filled out its play,

"The Countess Cathleen" was the name I gave it,

She, pity-crazed, had given her soul away

But masterful Heaven had intervened to save it.

I thought my dear must her own soul destroy

So did fanaticism and hate enslave it,

And this brought forth a dream and soon enough

This dream itself had all my thought and love.

And when the Fool and Blind Man stole the bread

Cuchulain fought the ungovernable sea;

Heart mysteries there, and yet when all is said

It was the dream itself enchanted me:

Character isolated by a deed

To engross the present and dominate memory.

Players and painted stage took all my love

And not those things that they were emblems of.

III

Those masterful images because complete

Grew in pure mind but out of what began?

A mound of refuse or the sweepings of a street,

Old kettles, old bottles, and a broken can,

Old iron, old bones, old rags, that raving slut

Who keeps the till. Now that my ladder's gone

I must lie down where all the ladders start

In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.

Having introduced his theme in Part I, at the beginning of the next part he refers to "The Wanderings of Oisin," an early work, a long epic poem that he had considered complete in 1887 (see Unterecker 48), although he worked over it thoroughly later. As he reminds us here, the legendary Oisin, "led by the nose" by his immortal lover, Naimh, visited three islands with her, experiencing adventures, and also a long sleep ("vain repose") far from this physical earth. What was all this about? The poet feels now that it was simply the product of an "embittered heart," after the failure of romance in his own life. In a similar vein, the next two stanzas refer to his plays, The Countess Cathleen and On Baile's Strand, in both of which, he realises now, he was again projecting his own personal feelings, but putting all his efforts into the way he presented them. Of his dramatic output, therefore, Yeats says, "Players and painted stage took all my love, / And not those things that they were emblems of."

In this late poem, however, his resolve is firm. He is determined not to lose sight of his true subject. Instead, he will immerse himself in it. The poem ends with the lines: "I must lie down where all the ladders start,/ In the foul rag-and-bone-shop of the heart." John Unterecker notes that the word "heart" is "strategically placed in each section" of this three-section poem (289), and indeed the last lines remind us of the opening stanza, in which he had said, "being but a broken man, / I must be satisfied with my heart." The poet feels that his "circus animals" have left, deserted him, gone for good, along with all the trappings of performance: "Those stilted boys, that burnished chariot," and so on. Nothing could be less romantic than the "foul rag-and-bone shop" he is left with at the end.

Since it has long been a thread in his thinking, this resolution might seem to bring his work full circle. But it is a very far cry from the yearning and pleading of "He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven." It lacks the anguished perturbation of "The Cold Heaven." And it goes beyond the brief, rather huffy, posturing of "The Coat." In short, it marks the end of a process in his poetry, away from poeticising towards the "personal utterance" he aimed at in (Autobiographies 102). Modernism had come and nearly gone during this process. Perhaps the later poetry leaves him closest, not to the inarticulacies and obscurity of T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, but to the romantic poetry of the early 1940s — not in its flamboyance and neo-Apocalyptic portentousness, but in its revolt against materialism, politicisation and all the other -isms that compromise humanity's "heart." The irony is, however, that surely the best-known and most popular of the poems considered here is still "He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven."

Bibliography

Foster, R. F. W. B. Yeats: A Life. Part I: The Apprentice Mage. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Unterecker, John. A Reader's Guide to William Butler Yeats. New York: The Noonday Press, 1959.

Yeats, W. B. Autobiographies. London: Macmillan, 1955.

_____. The Collected Works in Verse and Prose of William Butler Yeats, Vol. 1 (of 8): Poems Lyrical and Narrative. Stratford-on-Avon: Shakespeare Head Press, 1908. (Available on Project Gutenberg.)

Created 3 July 2021