[John McDonnell has graciously shared with readers of the Victorian Web his website with the electronic text, including scanned images, of the anonymous London Characters and the Humourous Side of London Life. With Upwards of 70 Illustrations apparently by a "Mr. Jones," which the London firm Stanley Rivers & Co. published in 1871. Brackets indicate explanatory material, such as interpretations of contemporary slang, by Mr. McDonnell.

![]() indicates a link to material not in the

original print version. — George P. Landow]

indicates a link to material not in the

original print version. — George P. Landow]

n discoursing concerning witnesses only a few days back, I took the opportunity of broaching the theory that the givers of evidence in the courts of justice were so far like true poets in that they were born, not made. Testis nascitur, non fit.

The first person who steps into the box on the present occasion is a remarkable example in point. He is "the witness who causes considerable amusement in court." Some persons may be disposed to find fault with the reporter for his uniform adherence to the use of the word "considerable." Why not "much," or "great?" No; the reporter is right. Other persons might cause "much," or "great," or "little" amusement; but "considerable" is the exact measure of this person's power of exciting risibility combined with perplexity and wonder. He does not do it intentionally; he does not know that he is doing it, and his fun is of a very dubious kind. Therefore the amazement which it causes is "considerable." Some laugh at him, others think him a fool; and the counsel who is cross-examining him is probably a little out of temper. This witness is not a complete success one way or another. He is neither a triumph to his own party, nor a defeat to the opposite side. All that he does in a definite way is to "cause considerable amusement in court."

The odd, unique, and almost paradoxical thing about this witness is that he never causes amusement in any degree,

considerable or otherwise, anywhere else. At home he is simply happy and stupid; abroad in the world, he is a heavy

impediment in everybody's way. He is a very unlikely flint indeed, and no one thinks of attempting to strike fire out of

him. He is about as likely a medium for that purpose as a slice of Dutch cheese. It is only when you pen him in a

witness-box, and strike him stupid with your legal eye, in presence of judge and jury, that you can make him yield anything

that is at all calculated to afford either amusement or instruction.

The odd, unique, and almost paradoxical thing about this witness is that he never causes amusement in any degree,

considerable or otherwise, anywhere else. At home he is simply happy and stupid; abroad in the world, he is a heavy

impediment in everybody's way. He is a very unlikely flint indeed, and no one thinks of attempting to strike fire out of

him. He is about as likely a medium for that purpose as a slice of Dutch cheese. It is only when you pen him in a

witness-box, and strike him stupid with your legal eye, in presence of judge and jury, that you can make him yield anything

that is at all calculated to afford either amusement or instruction.

He produces his considerable amusement (not with any design on his part, however,) by means well known to the two end men in a band of [Negro] serenaders.

Counsel screwing his glass in his eye, and putting on his most searching expression, says:---

"Now, sir; on your oath, did you not know that the deceased had made a will?" The witness hesitates and looks idiotic.

"Answer me, sir," roars the counsel, "and remember you are on your oath. Did you not know that the deceased had made a will?"

The witness answers at last, "Well, sir, I was;" which "causes considerable amusement in court," and greatly provokes the examining counsel.

"Now, sir, since I have been able to screw so much out of you, perhaps you will answer me this question: "What did the deceased die of?"

The witness does not appear to understand.

"What did the deceased die of?" the counsel repeats.

"He died of a Tuesday, sir," says the witness with the utmost gravity. And of course the audience go into convulsions and the crier has to restore order in court.

This witness is never of the slightest service in elucidating a case, and counsel are generally glad to get rid of him, except when the proceedings are getting flat, and want enlivening. Some counsel like a butt of this kind to shoot the arrows of their wit at; just as wanton street-boys like to tease and make sport of an idiot.

The next witness who steps into the box is a charge-sheet in himself, so expressive is he in every feature, and in his whole

style, of a tipsy row in the Haymarket, with beating of the police, and attempts to rescue from custody. It is quite

unnecessary for the active and intelligent officer to enter into details. We see the case at a glance. Mr. Slapbang has been

making free. He has visited a music hall or two, where he has joined in the chorus; he has danced at a casino; he has

partaken of devilled kidneys at a night supper-room; and visiting all these places in a jovial and reckless humour, he has

disregarded that wholesome convivial maxim which says that you should never mix your liquors. Mr. Slapbang has

mixed his liquors, the consequence being a disposition to beat his stick against lamp-posts, to wake the midnight echoes

with "lul-li-e-ty," and to show his independence by resisting the authority of the police, and perhaps offering them that

most unpardonable of all insults, known to the force---"voilence."

The next witness who steps into the box is a charge-sheet in himself, so expressive is he in every feature, and in his whole

style, of a tipsy row in the Haymarket, with beating of the police, and attempts to rescue from custody. It is quite

unnecessary for the active and intelligent officer to enter into details. We see the case at a glance. Mr. Slapbang has been

making free. He has visited a music hall or two, where he has joined in the chorus; he has danced at a casino; he has

partaken of devilled kidneys at a night supper-room; and visiting all these places in a jovial and reckless humour, he has

disregarded that wholesome convivial maxim which says that you should never mix your liquors. Mr. Slapbang has

mixed his liquors, the consequence being a disposition to beat his stick against lamp-posts, to wake the midnight echoes

with "lul-li-e-ty," and to show his independence by resisting the authority of the police, and perhaps offering them that

most unpardonable of all insults, known to the force---"voilence."

When Mr. Slapbang appears in the dock he makes a great effort, conscious of the presence of his friends, to keep his "pecker" [nose] up. The gloss and glory of his attire have been somewhat dimmed by a night's durance in the cells; but what he has lost in this respect he endeavours to make up for by a jaunty devil-may-care manner. He says he was "fresh," or "sprung," and "didn't know what he was doing," with quite a grand air, as if it were a high privilege of his order to get drunk and resist the police. His manner almost implies that it is quite a condescension on his part to come there and allow the magistrate to have anything to say in the matter. There is not such a very great difference between the conduct of this gentlemanly offender and that of the hardened criminal who throws his shoe at the judge, or declares, when sentence is pronounced, that he "could do that little lot on his head." Mr. Slapbang throws insolent glances at the bench, and when he is fined, instantly brings out a handful of money with an air that says plainly---"Fine away; make it double if you like: it's nothing to me." When Mr. Slapbang "leaves the court with his friends," he is the centre of a sort of triumphal procession: you would not think that he had been subjugated to the authority of the law, but rather that he had triumphed over it. His "friends" are very like himself. In most cases they are the companions of his revelry, who have been more fortunate than Mr. Slapbang in eluding the clutches of the police. When Mr. Slapbang leaves the court with his friends, he usually proceeds direct to the first public-house, where the company sarcastically drink to the jolly good health of the "beak" [magistrate].

The witness who insists that black is white is one of those self-conceited persons, who, when they once say a thing, stick to

it at all hazards. He has no intention of being dishonest, or of saying that which is not true, but he has a great idea of his

own infallibility, and a nervous dread of being thought the weak-minded person that he really is. He is the sort of person

who likes to be an authority in a public-house parlour; who cannot bear to be contradicted, and who will not allow any

authority to overweigh his own. I have heard him in the pride of his knowledge---for he pretends to know

everything---and in the fulness of his conceit, make a bet that "between you and I" is correct, and refuse to be convinced of

his error, even when the decision has been given against him by a referee of his own choosing.

The witness who insists that black is white is one of those self-conceited persons, who, when they once say a thing, stick to

it at all hazards. He has no intention of being dishonest, or of saying that which is not true, but he has a great idea of his

own infallibility, and a nervous dread of being thought the weak-minded person that he really is. He is the sort of person

who likes to be an authority in a public-house parlour; who cannot bear to be contradicted, and who will not allow any

authority to overweigh his own. I have heard him in the pride of his knowledge---for he pretends to know

everything---and in the fulness of his conceit, make a bet that "between you and I" is correct, and refuse to be convinced of

his error, even when the decision has been given against him by a referee of his own choosing.

"Sir," he said, rising and addressing the chairman one evening when a new comer in the parlour ventured to disagree with his view of a certain matter---"Sir, I have used this room now for five-and twenty years. Is that so, sir?"

The chairman admitted that it was so---with much respect for the fact.

"And in all that time, have you ever heard me contradicted before?"

"No," says the chairman, "never."

"Very well, then," says our friend. And with that sits down, satisfied that the bare mention of the fact will be sufficient to deter any one from a repetition of the offense which has just roused his indignation.

This witness always enters the box with the fond idea that he will prove "too much" for the counsel, but in the end it generally happens that counsel prove too much for him. Conceit is like pride---liable to have a fall; but, unlike pride, it does not always feel the smart. It has a thick skin.

The witness who expresses astonishment and indignation at the doubts which counsel throw upon his accuracy and

veracity is a variety of the same type. He is also conceited, but he has, at the same time, an inordinate idea of his own

importance. He is a man who studies appearances, and "makes up" for the character which he delights to enact through

life. He loves to be grumpy and testy, and in his own sphere he is a sort of Scotch thistle who allows no one to meddle with

him with impunity. Naturally when an audacious hand, gloved with the protection of the law, rudely seizes hold of him,

and blunts the points of his bristles, he doesn't like it. He is an easy prey to counsel, as every witness is who stands upon his

dignity or importance, and gets upset from that high pedestal.

The witness who expresses astonishment and indignation at the doubts which counsel throw upon his accuracy and

veracity is a variety of the same type. He is also conceited, but he has, at the same time, an inordinate idea of his own

importance. He is a man who studies appearances, and "makes up" for the character which he delights to enact through

life. He loves to be grumpy and testy, and in his own sphere he is a sort of Scotch thistle who allows no one to meddle with

him with impunity. Naturally when an audacious hand, gloved with the protection of the law, rudely seizes hold of him,

and blunts the points of his bristles, he doesn't like it. He is an easy prey to counsel, as every witness is who stands upon his

dignity or importance, and gets upset from that high pedestal.

The young lady whose affections the defendant has trifled with and blighted is generally of the order of female known as "interesting." And when she is interesting she always gains the day. A judge recently stated---almost complained---that there is no getting juries to find a young and interesting female guilty of anything---even when guilt is brought home to her without the possibility of doubt. Counsel know this well, and, I am told, always instruct a young and interesting female how to comport herself so as to make an impression upon the jury.

The stage directions, I believe, are something like this. "Enter the box (or the dock, as the case may be) with your veil down. This gives me occasion to tell you to raise your veil, and show your face to the jury. When you do this burst into tears and use your white cambric pocket handherchief. Then let the jury see your pretty eyes red with weeping, and your damask cheek blanched with anguish and coursed with bitter tears. When you are hard pressed by the opposing counsel, begin to sob, and grasp the rail as if for support. You will then be accommodated with a scent-bottle and a chair; and the jury will think the cross-examining counsel a brute, and you an injured angel."

Observation of these directions by a young and interesting female never fails. She will get clear off, even if she has murdered her grandmother.

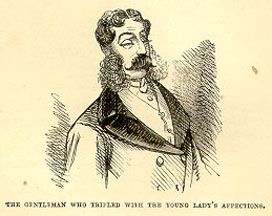

In a simple case of blighted affection, there is no need to take so much trouble. Only let the lady be well dressed, and look

pretty, and it is obvious at once (to the jury) that the defendant is not only heartless and cruel in the last degree, but utterly

insensible to the charms of youth and innocence. Yet in nine cases out of ten this interesting female who weeps and sobs,

and uses her smelling bottle, is an artful schemer. Look at the gentleman who trifled with her affections. Is that the sort of

person to kindle in any female breast the devouring flame of love? Is he the sort of person to love any one but himself, or

cherish anything but his whiskers? He is a trifler, it is true, but he has not trifled with that interesting and artful female's

heart, because she has no heart to trifle with. She might sue him for wasting her time, but not for breaking her heart.

In a simple case of blighted affection, there is no need to take so much trouble. Only let the lady be well dressed, and look

pretty, and it is obvious at once (to the jury) that the defendant is not only heartless and cruel in the last degree, but utterly

insensible to the charms of youth and innocence. Yet in nine cases out of ten this interesting female who weeps and sobs,

and uses her smelling bottle, is an artful schemer. Look at the gentleman who trifled with her affections. Is that the sort of

person to kindle in any female breast the devouring flame of love? Is he the sort of person to love any one but himself, or

cherish anything but his whiskers? He is a trifler, it is true, but he has not trifled with that interesting and artful female's

heart, because she has no heart to trifle with. She might sue him for wasting her time, but not for breaking her heart.

Entered the Victorian Web 20 October 2001; last modified 19 July 2014