This is a slightly extended version of a review first published under the title of "An Absurd and Brutal Mindset" in the Times Literary Supplement (29 March 2024: 19). Page references, links and illustrations have been added here. [Click on the images for larger pictures and more information where available.]

This is the "true story" of James Pratt and John Smith, two men of previously good character, who were spied on through a keyhole and a gap made in an adjacent stable roof, while engaged in an intimate consensual encounter. They were then reported, arrested and detained in Horsemonger Lane Goal, before being tried at the Old Bailey. Here, on the witnesses' evidence, they were convicted of sodomy. An added complaint was that their activity might have been visible through the upstairs back window from a side street. Despite the determined efforts of James's wife, the testimonies of employers, and the interventions of the more fair-minded among the powerful — notably, Hensleigh Wedgwood, the magistrate who committed them for trial — no reprieve was granted. They were hanged at Newgate on 27 November 1835, the last to be executed for such a "detestable offence" (67). William Bonnell, the elderly silver-haired lodger who had brought Smith and Pratt to his rented room, was transported to Van Diemen's Land, where he died in 1841. He was being spoon-fed in a hospital catering mainly for those with mental health problems.

At the trial, nothing was made of the invasion of John and James's privacy, or the unfair implication that they had endangered public morals. Unequal to speaking for themselves, they had no right to a defence lawyer. They simply pleaded not guilty. But Chris Bryant's concern is not just to reveal a particular injustice. He sets out to expose the failings of the whole official system. The historical context in which he sets this case is staggering in its depth and scope. Anyone interested in nineteenth-century society and its agencies will find it incredibly revealing.

The backgrounds and appearances of all those involved, at every level, are recreated: even Smith, with a name to strike despair into any would-be family historian, emerges as an individual — once a satisfactory employee, the sole support of his aged mother, shortish, stocky and fair-complexioned. From Pratt and Bonnell, about whom much more is known, Bryant creates a picture of the daily lives of the nineteenth-century servant class, the opportunities for like-minded men to meet, and the prevalent attitudes towards them (few as enlightened as Jeremy Bentham's, but then he knew something about human nature). Meanwhile, through the better records available of those higher up in the social order, Bryant conveys a whole official mindset, absurd and brutal in its prejudices. This is not a matter of ahistorical hindsight. The discrimination, between upper-class men like the explorer and Tory M.P. William Bankes (1786-1855) of the grand house of Kingston Lacy in Dorset, whom the jury quickly acquitted of a similar act in 1833, and the struggling poor, blamed for spreading moral decay, was blatant. Added to all this, Bryant explains every part of the legal process and its aftermath, down to the very structure of the gallows and the action of the hangman's rope.

But he never loses sight of the central narrative. Among the many scenes that stay in the mind, one is of Dickens, as a young journalist, glimpsing the dejected men in the condemned cell at Newgate. This is the original account in Dickens's Sketches by Boz (1836) on which Bryant draws:

In the press-room below, were three men, the nature of whose offence rendered it necessary to separate them, even from their companions in guilt. It is a long, sombre room, with two windows sunk into the stone wall, and here the wretched men are pinioned on the morning of their execution, before moving towards the scaffold. The fate of one of these prisoners was uncertain; some mitigatory circumstances having come to light since his trial, which had been humanely represented in the proper quarter [this man's case was more ambiguous; he was indeed reprieved]. The other two had nothing to expect from the mercy of the crown; their doom was sealed; no plea could be urged in extenuation of their crime, and they well knew that for them there was no hope in this world. “The two short ones" [Swann, a private from the Scott's Fusilier Guards, was taller than Pratt and Smith] the turnkey whispered, “were dead men.”

The man to whom we have alluded as entertaining some hopes of escape, was lounging, at the greatest distance he could place between himself and his companions, in the window nearest to the door. He was probably aware of our approach, and had assumed an air of courageous indifference; his face was purposely averted towards the window, and he stirred not an inch while we were present. The other two men were at the upper end of the room. One of them, who was imperfectly seen in the dim light, had his back towards us, and was stooping over the fire, with his right arm on the mantel-piece, and his head sunk upon it. The other, was leaning on the sill of the farthest window. The light fell full upon him, and communicated to his pale, haggard face, and disordered hair, an appearance which, at that distance, was ghastly. His cheek rested upon his hand; and, with his face a little raised, and his eyes wildly staring before him, he seemed to be unconsciously intent on counting the chinks in the opposite wall. We passed this room again afterwards. The first man was pacing up and down the court with a firm military step — he had been a soldier in the foot-guards — and a cloth cap jauntily thrown on one side of his head. He bowed respectfully to our conductor, and the salute was returned. The other two still remained in the positions we have described, and were as motionless as statues. [Ch. XXV, "A Visit to Newgate," referenced extensively in Bryant 188-89]

Another scene that stays in the mind is that of the "Hanging Cabinet" or final court of appeal, where neither letters in support of the men, nor James's wife's petition for her husband's life, were produced. Convening at the Brighton Pavilion, the privy councillors simply scurried through the business before attending the evening's grand banquet.

Left: The King and His Ministers in Council © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. Right: The Banqueting Room at the Brighton Pavilion. [Click on this image for more information, and to see a larger version.]

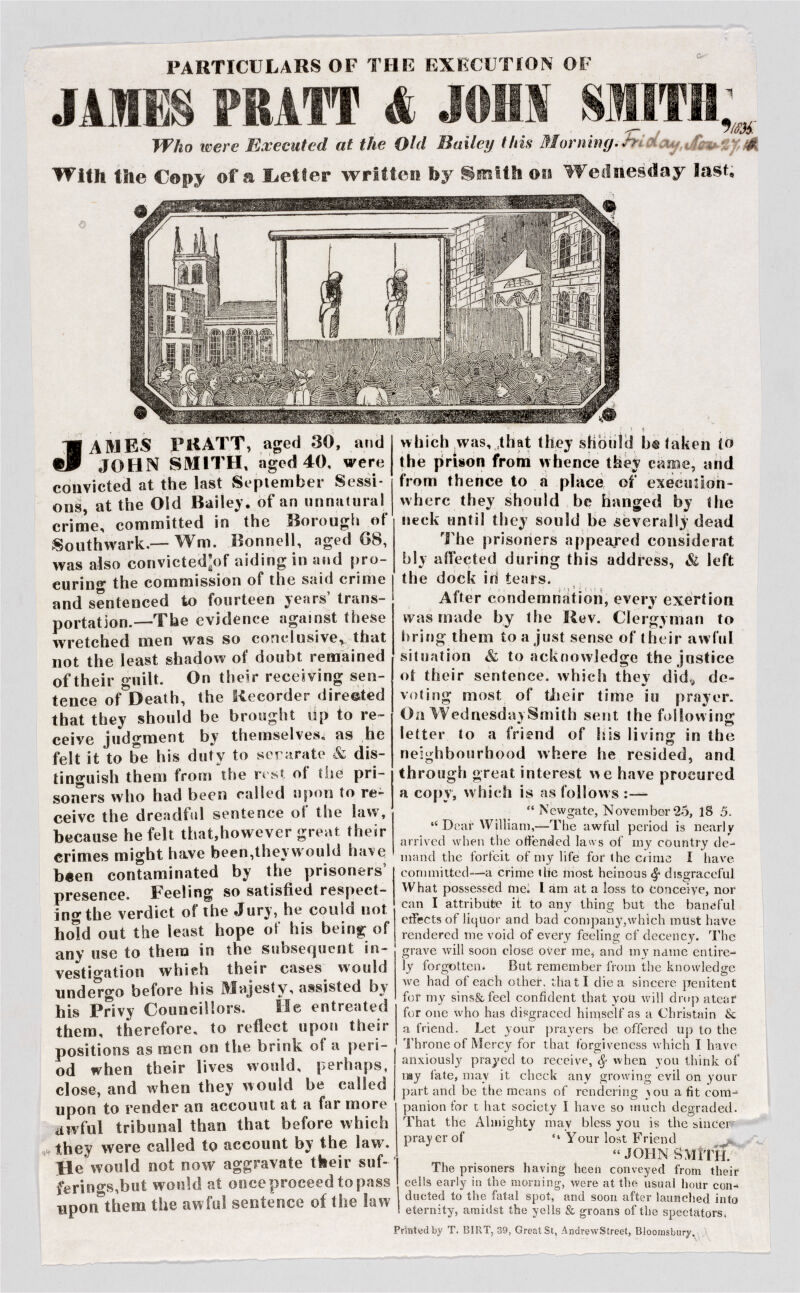

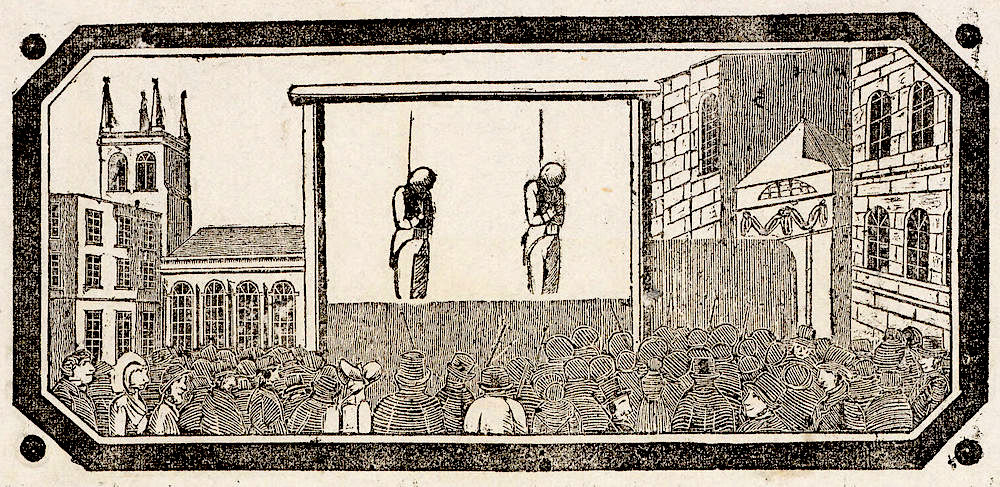

Memorable too is the final dispatch outside Newgate. At the "condemned sermon" (218), James would probably have taken leave of the wife who had tried so hard to save him. Now, having groaned loudly and "repeatedly collapsed" as the hangman's assistants looped the ropes round them in readiness (231), he followed John to the scaffold amid the hissing of the spectators.

Left: The Execution Broadside about the two men in the Repository of Harvard Law School Library. Right: Close-up of woodcut at the top (persistent link https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:hls.libr:912568?n=35).

Bryant's appendix, "Executions for Sodomy between Consenting Adult Men" (247-48), indicates that Smith and Pratt were the last of 39 adult men executed for the same reason since the turn of the century, another man only having evaded the noose by committing suicide in gaol. But harshness and hypocrisy continued: towards the end of the Victorian period, in 1895, people mocked and spat on Oscar Wilde on the platform at Clapham Junction, when he was being taken to Reading Goal. Wilde's case is, of course, famous, but the earlier case is not, and Bryant's meticulous research presents it in all its poignancy for the first time. In the end, those who stand condemned are not the men who stood side by side in the dock, overwhelmed by the turn their lives had taken, but the sanctimonious officers of state to whom such lives meant nothing, and who consigned them to the gallows under a patently inhumane law.

Bibliography

Book under review: Bryant, Chris. James and John: A True Story of Prejudice and Murder. London: Bloomsbury, 2024. 317 + xi pp. Hardback £19.95. ISBN: 978-1526644978

Created 6 November 2024