[The author has kindly shared this essay from her blog. which readers might wish to consult. Click on images to enlarge them. — George P. Landow.]

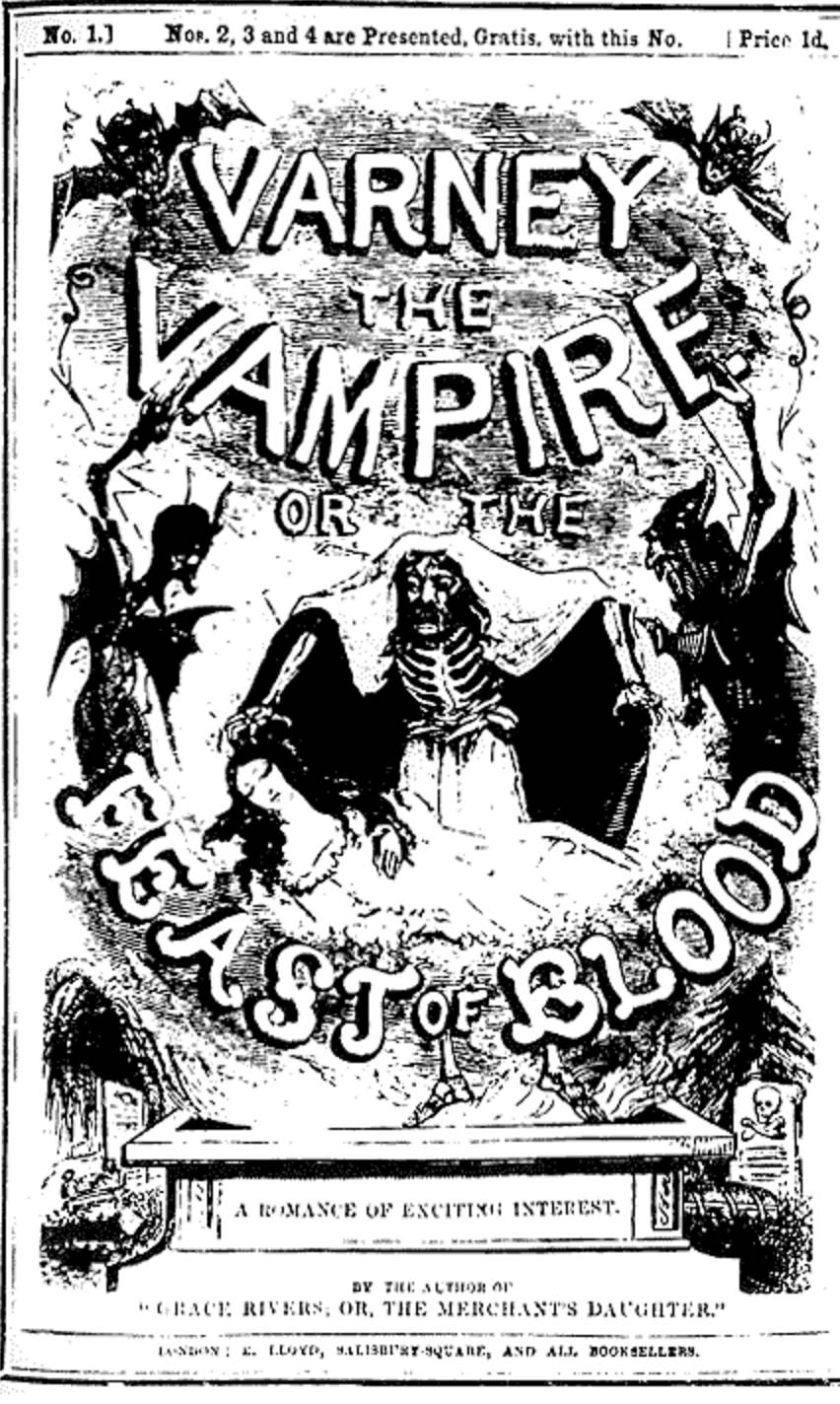

he 1840s ushered in an era of luridly illustrated gothic tales which were marketed to a working-class Victorian audience. These stories, told in installments and printed on inexpensive pulp paper, were originally only eight pages long and sold for just a penny – giving rise to the term “penny bloods” or “penny dreadfuls.” With titles such as Varney the Vampire and Sweeney Todd: the Demon Barber of Fleet Street, these types of publications were wildly popular, especially with young male readers, and it was not long before the Victorian public began to make a connection between various juvenile crimes and misdemeanors and the consumption of this (allegedly) depraved material.

Left: Black Bess or the Knight of the Road, a tale featuring Dick Turpin and his horse. The cover provides a perfect emblem of the penny-dreadful’s attack on moral authority in the way it shows the legendary highwayman battering a red-coated soldier — the obvious symbol of empire and authority. Right: Varney the Vampire, a precursor to both the next century’s fascination with vampires.

By the 1880s, concern over penny dreadfuls leading children into lives of crime and vice sparked what the Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction describes as a “middle-class moral panic.” Many urged that the publication and consumption of penny dreadfuls be criminalized. An article in the 1895 issue of Publisher’s Circular fully supports this idea, at the same time acknowledging the difficulties of enforcing such a law, stating:

Coroners’ juries have condemned it, and coroners themselves have regretted that the law does not interfere to suppress it. In a criminal trial which has just concluded, several specimens of this gory and sensational stuff were in evidence, and the titles (to go no farther) are certainly suggestive of dark and ruthless deeds. We are quite sure it is not to the interest of the nation that the rising generation should be nourished on the literary fare enclosed within the covers of a “Penny Dreadful.” Yet we do not very well see how the reading of the people is to be supervised by the police. Reform, we fancy, must be left to that best of all detectives — public opinion. [290]

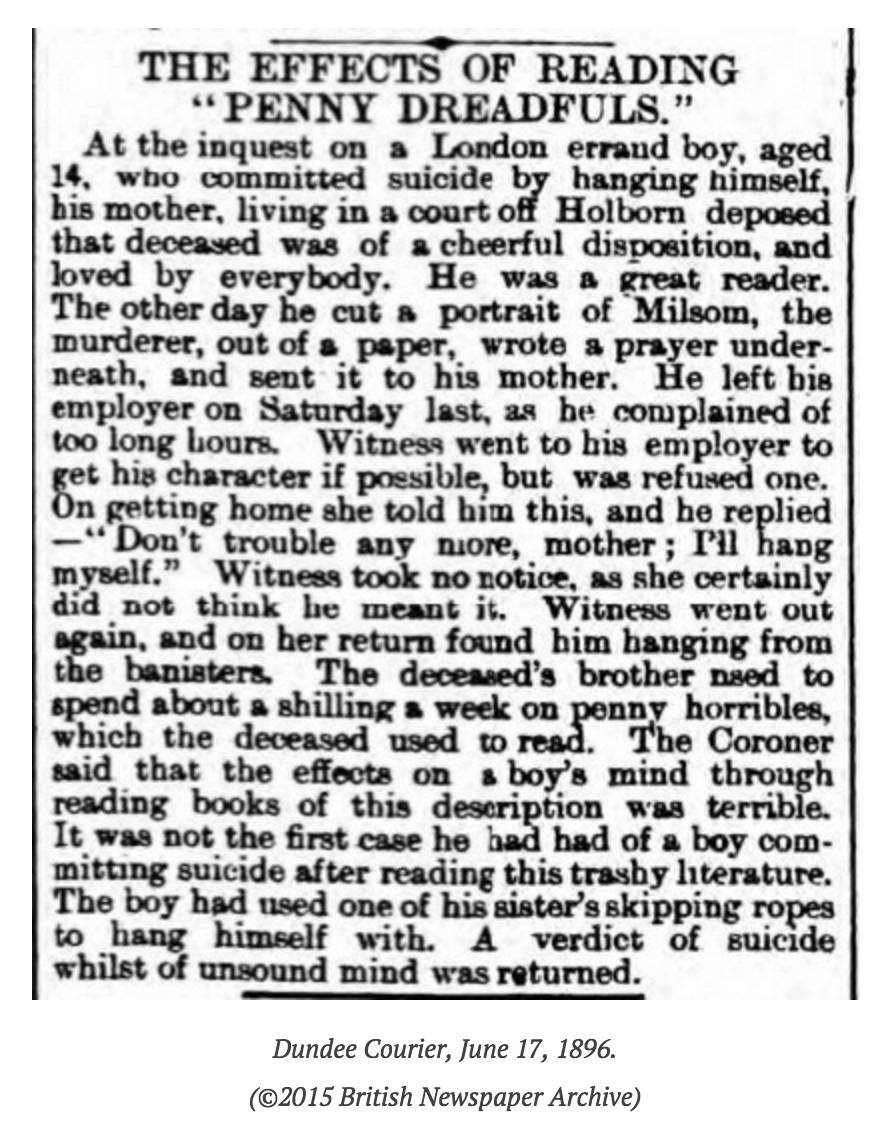

As is often the case, the court of public opinion was divided. Those railing against the penny dreadful made several arguments for banning or criminalizing the publications. In support of this argument, newspapers and magazines of the day gave countless examples of boys who, after reading a penny dreadful, had robbed their employer or embarked on some other criminal enterprise. For example, the 1895 The Speaker relates the tale of a “half-witted boy” (367) who, after reading a great many penny dreadfuls, went and killed his mother. And an 1896 edition of the Dundee Courier attributes the suicide of a fourteen-year-old London errand boy to the negative effects of reading “penny horribles.”

Some Victorian educators asserted that penny dreadfuls glamorized a life of crime. While others argued that the adventure stories contained within the pages of a penny dreadful encouraged working-class British youths to be dissatisfied with the mundanity of their day-to-day lives and to aspire to riches and adventure outside their class. As an article in the 1895 Publisher’s Circular states:

There is something intensely pathetic in this hunger of the little soul for something beyond its own narrow, monotonous ken. In proportion as its circumstances are more sordid, more confined, more lacking in any interest to break the prosaic realism of its daily round, so much the more does the child, in its unsatisfied sense of the beautiful and the artistic, go blindly out to seek what food it can get. [593]

The same article goes on to state that since the only “food” available was vulgar and shocking pulp fiction, it was only to be expected that, in their “crude, untutored ignorance,” working-class youths would choose to model their behavior on “swaggering highwayman and penny dreadful heroes.” As a result of this, the author concludes “No wonder we find our newspapers full of boy and girl suicides and child-criminals. And how can the young lives caught thus early in the snare, when once the prison shadows have enclosed them, ever become happy or useful members of society? They are swept away in the whirlpool before they have really begun to exist” (593).

Despite all the arguments in favor of it, criminalizing penny dreadfuls was generally acknowledged to be an impossibility. So too was driving the publishers out of business. The penny dreadful industry was simply too big and too popular. In the article “Penny Fiction,” in the July 1890 issue of The Quarterly Review, Francis Hitchman rails against the pervasiveness of the penny dreadful:

In a lane not far from Fleet Street there is a complete factory of the literature of rascaldom — a literature which has done much to people our prisons, our reformatories, and our Colonies, with scapegraces and ne’er-do- wells. At the present time no fewer than fifteen of these mischievous publications are in course of issue from this one place. They are not, it is true, very new, but they have a steady and considerable sale in the back streets, and are constantly advertised as in course of re-issue. [152]

With prosecution and eradication off the table, Victorian moralists were forced to come up with another solution to the problem of the pernicious penny dreadful. Ultimately, this solution was the introduction of an alternative type of publication. Dubbed “penny delightfuls” by one Victorian publisher, this new penny fiction was touted as being clean, healthy, and moral. Many hoped it would serve as an antidote to the penny dreadful. As an article in an 1895 edition of The Review of Reviews Annual, titled “How to Counteract the Penny Dreadful,” asserts:

The best way to counteract the ‘penny dreadful’ is to provide an equally attractive substitute, and the teachers might do a great deal by seeing that the young folk should have access to a good supply of healthy fiction. It may be that the teachers themselves will have to be taught first, if it is true, as I have seen it stated, that the pupil-teachers, as well as the boys in the higher standards, buy ‘penny dreadfuls’ and exchange them with one another. If that is so, the pupil-teachers betray a craving for fiction which had better be satisfied with what is healthy than with what is unhealthy. [418]

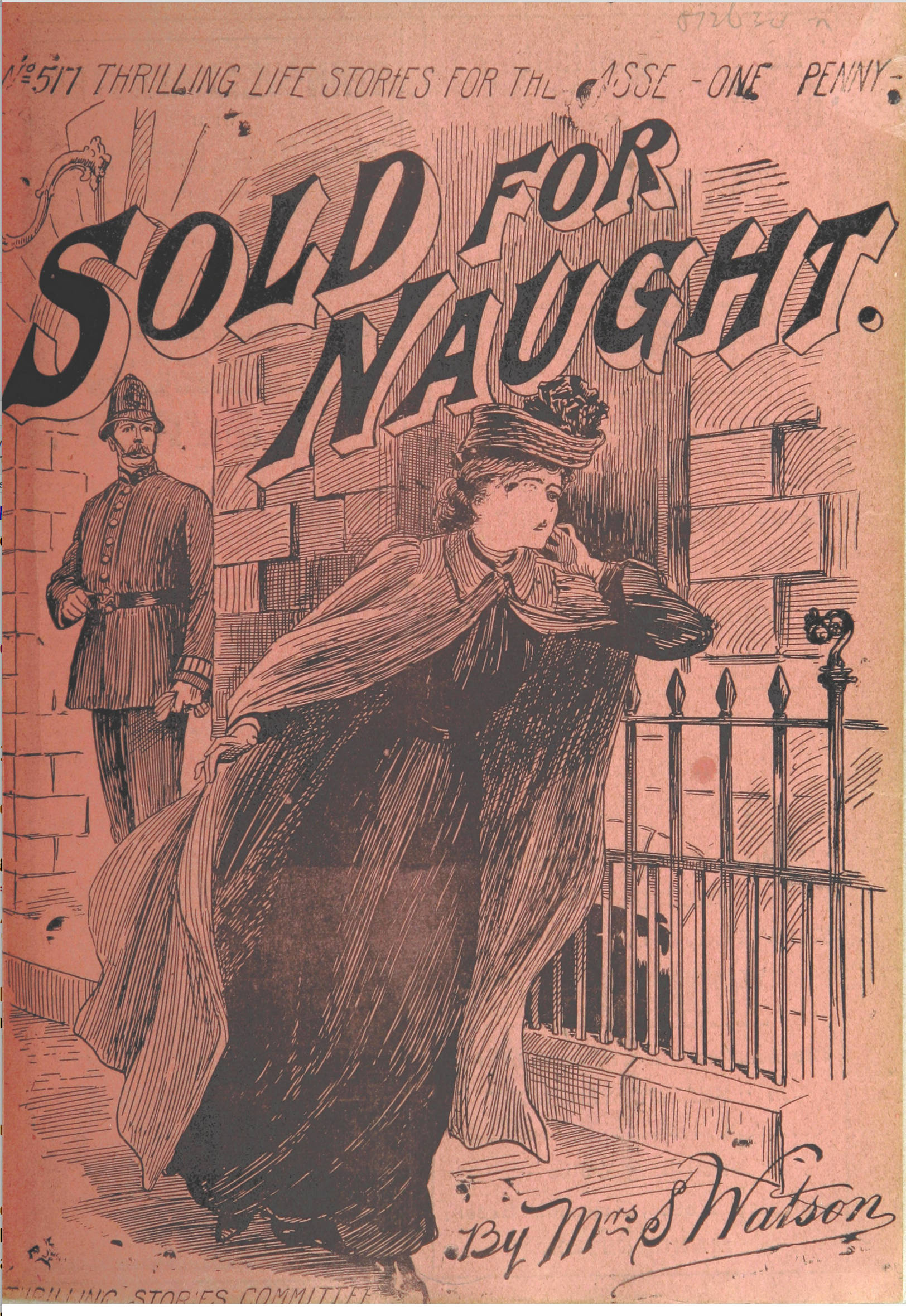

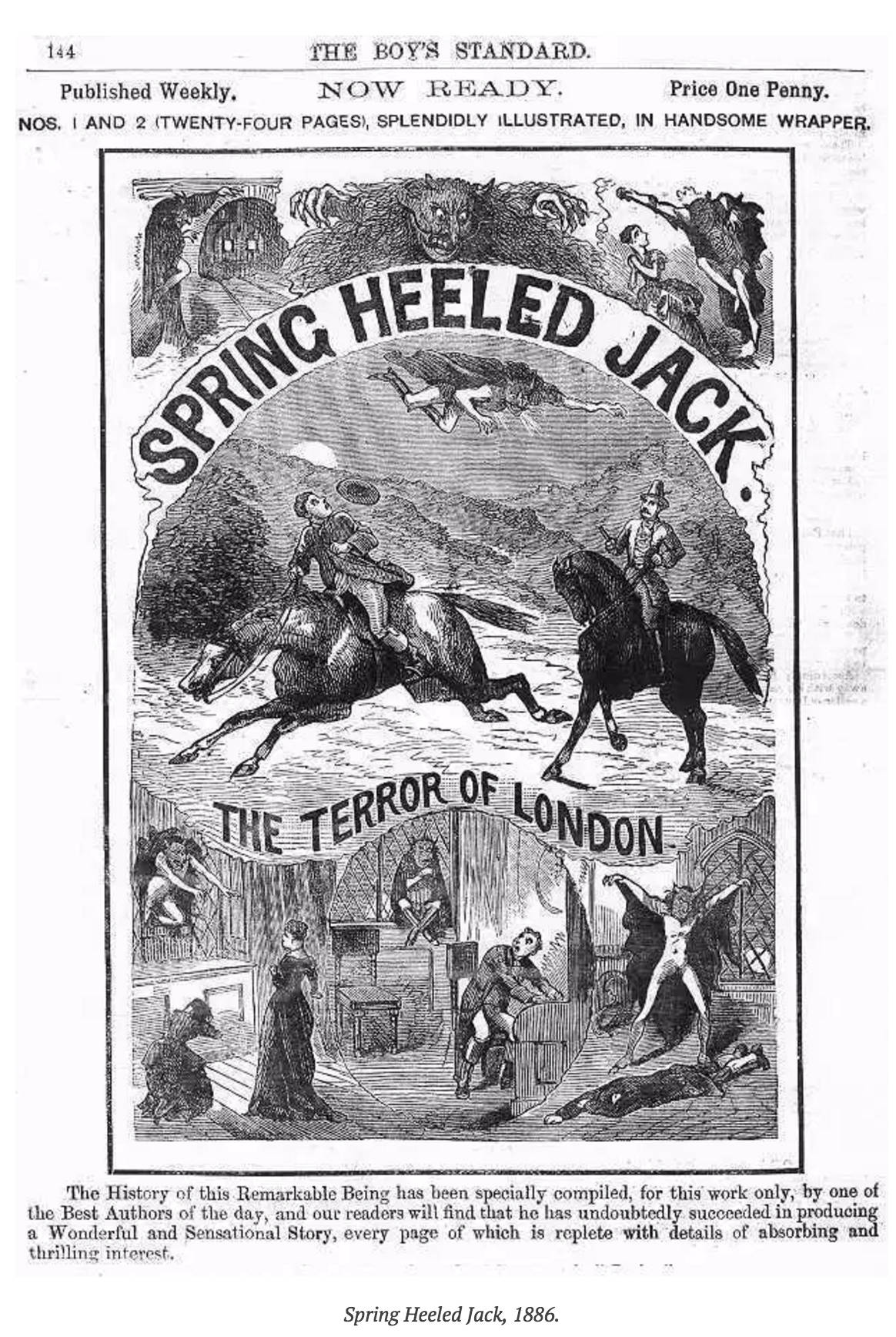

Sold for Naught and Spring-heeled Dick (an early super hero?) — two novels competing with the penny-dreadful for the attention of child readers.

There were some benefits to this late-Victorian moral panic. In Youth of Darkest England: Working-Class Children at the Heart of the Victorian Empire, Troy Boon states that the outrage over penny dreadfuls spurred on a “major transformation in the children’s publishing industry” (65). Suddenly, there was a profound interest in providing working-class youths with quality fiction.

But not all Victorians joined the moral crusade against penny dreadfuls. There were many individuals who questioned the tenuous connection between popular pulp fiction and juvenile crime. For example, an article in an 1895 Publisher’s Circular argues that “Because a misguided lad reads trash, and straightway commits a heinous crime, we need not rush to the conclusion that juvenile literature is going to the dogs by inculcating wrong lessons or holding up false ideals” (591). Thomas Wright similarly pointed out in an article in the 1881 Contemporary Review that “The evil commonly attributed to the dreadfuls is that they tend to corrupt boys morally, and in particular to make them dishonest. But this we venture to think is a mistaken idea. . . . There were robberies by errand boys when penny dreadfuls were not, and there would still be such robberies if the dreadfuls ceased to be” (35). Others skeptical about the supposedly dangeorous moral influence of the penny dreadfuls pointed to the far more graphic and immoral conduct of characters in mythology and the classics. As an article in an 1895 Publisher’s Circular points out: “The classics on the moral side are no better than they ought to be, yet they are studied in our schools and colleges, are lauded by critics and professors, and generally understood to be beneficial in their influence, while the ‘Penny Dreadful,’ which we are told is not immoral, is generally condemned” (383).

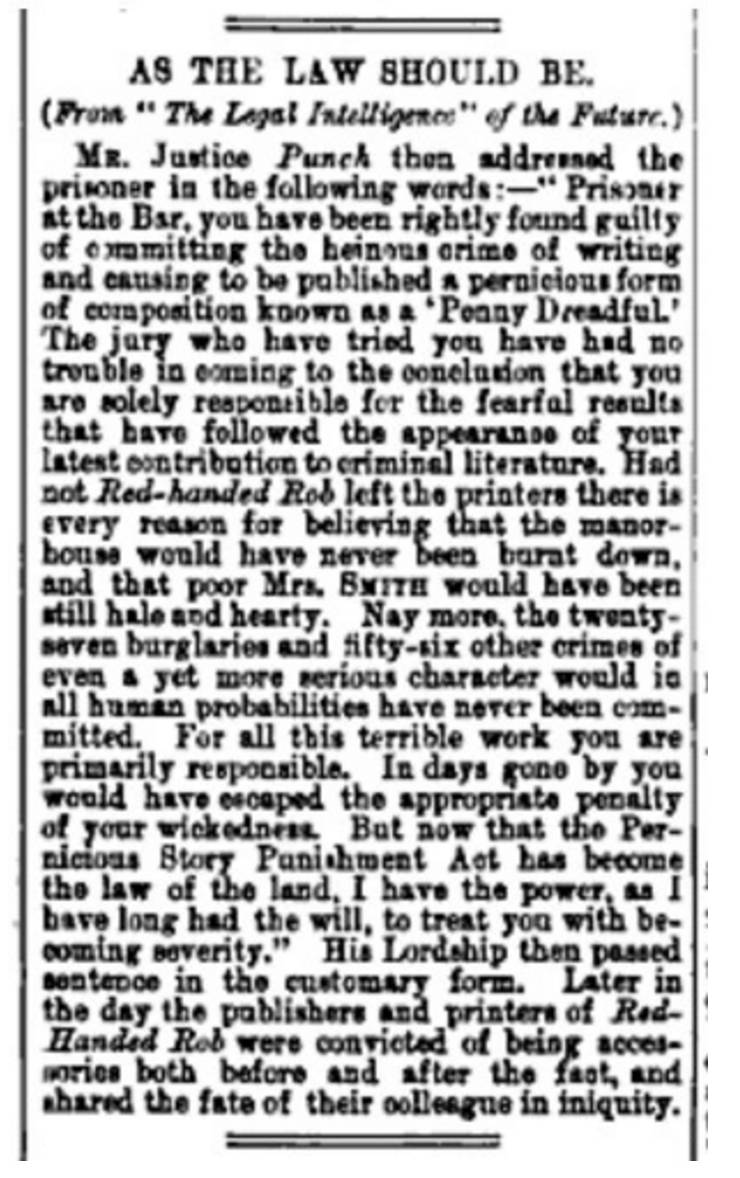

By the close of the century, even magazines like Punch were ridiculing the public’s outrage over penny dreadfuls with mock articles, caricatures, and poems. In “As the Law Should Be” (1895), for example, Punch makes reference to the “Pernicious Story Punishment Act,” under which a fellow is prosecuted for the “heinous crime” of writing penny dreadfuls (147).

Two views of the dangers of reading penny dreadfuls — the 1896 Dundee Courier’s report of a young man’s suicide supposedly caused by reading this kind of fiction (at left) and Punch’s mocking proposal a year earlier to make such reading illegal. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In the end, the penny dreadful was not driven out by the “penny delightful.” Instead, the gruesome tales, Gothic romances, and detective stories in Victorian pulp fiction took shape in the novels of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Today, the types of stories once vilified during the late-Victorian era are sources of some of our greatest entertainment. Occasionally, some members of the public still object on the grounds that this sort of fiction is inappropriate or harmful. Thankfully, just as with the penny dreadfuls, common sense usually prevails, for as an article in the 1895 Publisher’s Circular points out: “If fiction is to be confined by approved rules of gradual advancement, and by the experience of the majority in the routine of daily life, then we may bid farewell to romance” (383).

Works Referenced or quoted in this Article

Boon, Troy. Youth of Darkest England: Working-Class Children at the Heart of Victorian Empire. New York: Routledge, 2005.

“The Effects of Reading Penny Dreadfuls.” Dundee Courier. June 17, 1896.

Hitchman, Francis. “Penny Fiction.” The Quarterly Review. Vol. 171. London: John Murray, 1890.

“How to Counteract the Penny Dreadful.” The Review of Reviews Annual. Vol. XII. London: Mowbray House, 1895.

Mackay, T. “Penny Dreadfuls.” Time: A Monthly Magazine of Current Topics, Literature, & Art. Vol. VIII. London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1888.

“That Poor Penny Dreadful.” Punch. Vol. CVIII. London: Fleet Street, 1895.

“The Poor Little Penny Dreadful.” The Speaker. Vol. XII. London: Fleet Street, 1895.

The Publisher’s Circular. Vol. LXIII. London: Samson, Low, Marston, & Co., 1895.

The Publishers Circular. Vol. LXIV. London: Samson, Low, Marston, & Co., 1896.

Sutherland, John. The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction. New York: Routledge, 1988.

Wright, Thomas. “On a Possible Popular Culture.” The Contemporary Review. Vol. XL. London: Strahan & Co, 1881.

Last modified 12 January 2016