In transcribing the following paragraphs from the Internet Archive online version of The Imperial Gazetteer’s entry on British India — modern South Asia — I have expanded the divided the long entry into separate documents, expanded abbreviations for easier reading, and added paragraphing and links to material in the Victorian Web. The charts are in the original. This discussion of British India has particular importance because it immediately precedes the 1857 Mutiny and the subsequent major shift in its status as it came under the direct control of the British government rather than that of the East India Company, a private company.— George P. Landow]

The land-tax is the principal source of the Indian revenue. Throughout the greater portion of the presidencies of Bengal, namely, in the provinces of Bengal, Baliar, Benares, and Orissa (excepting Cuttack), and in some parts of the Madras presidency as the north Circars, and parts of Salem and other central districts the land is assessed under the zemindary or perpetual settlement; in most parts of the Madras presidency, in portions of that of Bombay, and in Cuttack, it is under the ryotwary settlement; and in the Bombay and Agra presidencies, with few exceptions, the rent is raised upon the village system a political arrangement.

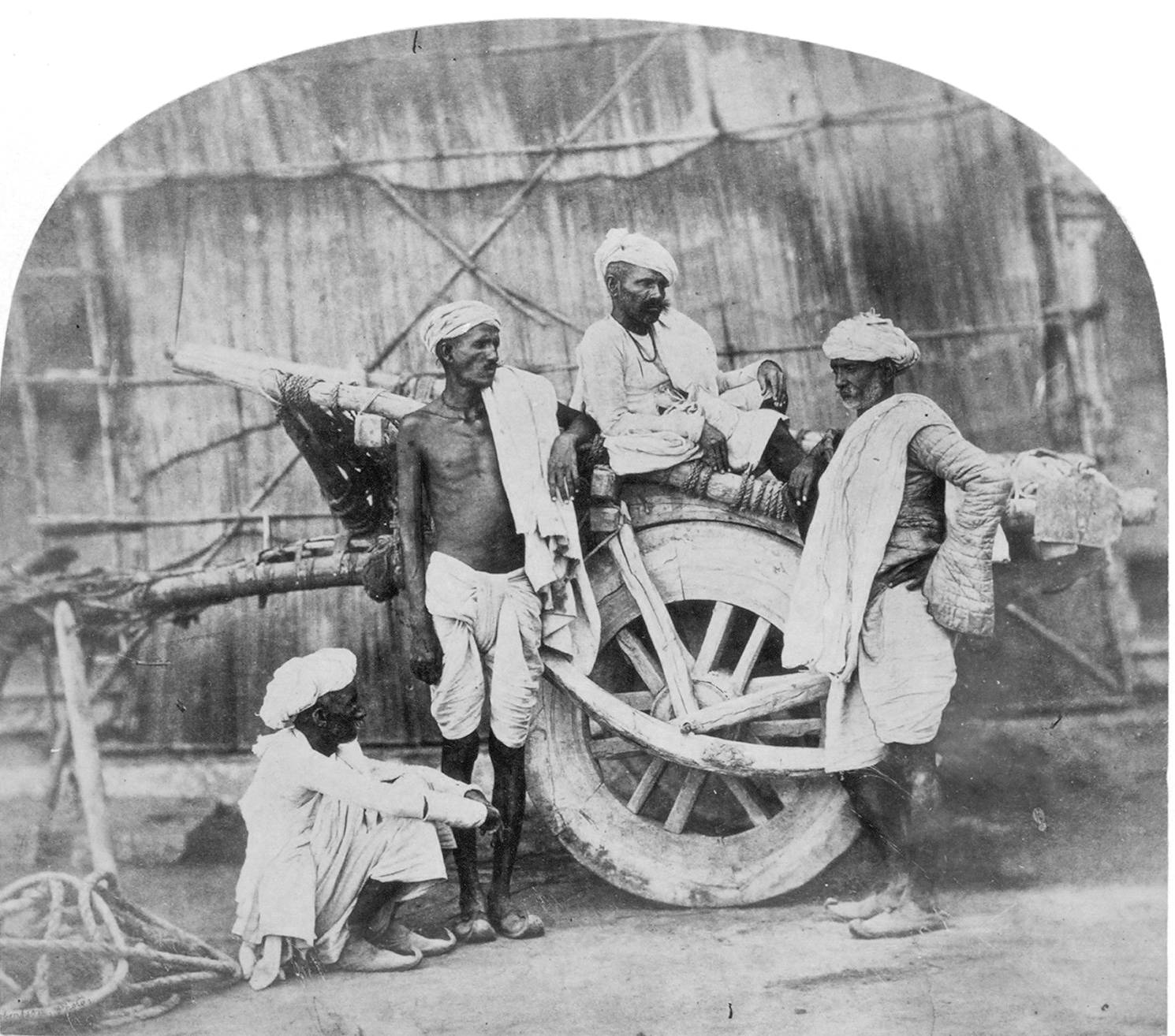

Two groups of tax collectors in Rajastan: Left: Goojur Hindoo Zemindars Rajpoutana. . Right: Jat Hindoo Zemindars Rajpoutana. [Click on images to enlarge them.]. Collection New York . 510d47dd-cc87-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.001.v. Click on images to enlarge them.

When the East India Company succeeded to the territories in Bengal, &c. previously held by the Mogul sovereigns, they found the revenue collected by officers named Zemindars, Talookdars, &c., whom, after a great deal of controversy, the Indian Government of Lord Cornwallis constituted the proprietors of the soil. With them a perpetual settlement was made the tax of the Government being fixed for ever at an amount calculated upon half the annual produce of the soil, for a certain term of years previously. This was the nominal amount of the tax, but in practice the sums levied were much below that amount, being frequently but one-fourth, and, in some localities, one-sixth of the produce; and the Zemindars appropriated the surplus of the half, in addition to being entitled to retain one-tenth of the amount levied as a remuneration for collecting the tax. The ryotwary system, introduced by Sir Thomas Munro into the territories of Madras, involves a levy on each cultivated field separately, and the contract exists between the government and the cultivator, without the intervention of the Zemindar or middleman.

The village system, under which most part of the presidency of Bombay, and all of that of Agra, are assessed, has prevailed from time immemorial throughout India, and is an institution peculiarly consonant with the habits and usages of the people. The villages are so many petty republics, each having its own separate organization and functionaries, who may thus be enumerated: the Potail or head of the village and local judge, the recorder, tax-gatherer, land-measurer, conductor of water, washerman, smith, coach-maker, potter, barber, watchman, astrologer, poet, and schoolmaster. These officers are chosen annually by the inhabitants of the village, and each has a share in the produce of the soil. The arrangement for the payment of the land- tax is here made by the Government with the Potail or head-man of the village. The lands, aggregately, are assessed at a certain amount, and if any members of the village community are unable to pay their share of the assess ment, the responsibility rests with the community the other members of which make up the deficiency by mutual arrangement.

Tax Revenues

We learn, from a valuable report on revenue statistics by Lieutenant-Colonel Sykes, that the land-tax in the Agra presidency, where the village system is in force, is collected with facility; the amount annually raised there exceeds £4,000,000 sterling the cost of collection being about 6¼ per cent. The maximum rate in that presidency is about 5s. 6d. per acre, the minimum 1s. 3d. and the average 3s. 7½d. on lands producing crops worth 200 rupees (£20) per acre. In four collectorates of the Deccan, also, where the land-tax is levied on the villages, the rate is no more than from 1s. 6d. to 3s. 2d. per acre. It was stated in 1847 that the increase of revenue in the north west. provinces in 40 years had amounted to 1 ,500,000 sterling or 75 per cent., and Colonel Sykes expresses his assent to the statement that this increase of revenue ‘has been attended with improvement in the condition of the rural population.’ — (Journal of the Statistical Society, vol. x. p. 247.) In the Agra presidency the amount of assessment has been settled with the villages for a period of 30 years, and in the Deccan and south Maharatta country for 20 years. In Bengal the permanency of the rent has so much fostered agriculture and extended cultivation, that the Zemindars in all parts are said to enjoy a revenue at least equal to, and in many places a great deal more than, the Government tax at the expense, however, of the ryots or cultivators. [II, 1273]

Bibliography

Blackie, Walker Graham. The Imperial Gazetteer: A General Dictionary of Geography, Physical, Political, Statistical and Descriptive. 4 vols. London: Blackie & Son, 1856. Internet Archive. Inline version of a copy in the University of California Library. Web. 7 November 2018.

Last modified 5 December 2018