Left: The doors to the exhibition. Right two Empresses of China’s Forbidden City the visitor first encounters. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Visitors enter this beautifully designed exhibition through doors in a wall painted imperial yellow, the color reserved for the Emperor, Empress, and their close associates, and then encounter a darkened room in which one after another of the portraits of Empresses become illuminated as a voice pronounces their names (see two photos above right). Such an introduction to these once-powerful women at the imperial court seems perfect for the exhibition, which runs from 18 August 2018 to 10 February 2019, after which it travels to Washington, D.C., and Beijing.

Left: Bridal headdress. Middle: A particularly elegant hairpin. Right: A view of the museum’s interior looking toward the bridge that leads into the exhibition..

Visitors next enter a brightly lit room that includes a bridal headdress on loan from Providence’s Rhode Island School of Design Museum (one of the relatively few objects not from Beijing’s Palace Museum) and an effective multimedia explanation (see immediately below) of the Empresses’ robes and the meaning of the symbols that cover them.

Two images of the multimedia introduction to the clothing worn by the subjects of the exhibition.

Much of the show is devoted to the exquisitely colored and embroidered silk garments worn by these women who resided at the center of power, and the exhibition designers did an excellent job not only by choosing extraordinarily beautiful examples but also by explaining their particular functions and iconography. The examples in the photographs immediately below well represent the beauty and quality of the many objects on display.

Left: Court Vest with Dragons and Clouds. Yongzheng period, 1723-35. Palace Museum, GU43482. Right: A more informal garment and a detail of the embroidery by the Imperial Silk Manufacture, Suzhou. The Imperial Worskshop in Beijing did the tailoring. Palace Museum.

Theatrical robe with peaches, butterflies, bats, and clouds and detail. Embroidery by Imperial Silk Manufactury, Suzhou, 1736-95. Lent by the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the John R. Van Derlip Fund. 42.9.118.

Some of the robes on display seem a bit of bait-and-switch: This magnificent garment shown directly above turns out not one likely to have been worn by a empress or consort, since as the exhibition label explains, “Qing imperial women were important consumers and patrons of court theater.” In other words, the only connection with the exhibition’s “Empresses of China’s Forbidden City” is that these empresses might have seen this garment. The label further explains that the robe “was probably for the role of imperial woman or goddess in a play performed during an imperial birthday celebration.” If that’s the case, it would be interesting to know to what extent, if any, the symbols and colors supposedly reserved solely for the Emperor, Empress, and highest level consorts were in fact worn by others.

As some of the beautiful and often fascinating objects on display in the exhibition make clear, several understated or completely unstated ideas weave their way through this brilliant exhibition, the most obvious of which, perhaps, is that these powerful women at the center of the great Chinese Empire were not Chinese! Just as the Hindoos of the Indian subcontinent were conquered by the Muslims from Persia, the Chinese empire that the Han had dominated fell to the Manchu and the Mongols. The history of these empresses includes nothing like the tale of Esther in which a woman of the conquered people marries the conqueror and saves her people. As one learns shortly after the exhibition begins, Han girls were not even allowed to become one of the Emperor’s many consorts. Only Manchu and Mongol women need apply; or rather since they were only thirteen years old when selected for the imperial harem, only their families need apply. (If entering the harem at thirteen years old makes the Emperors seem like pedophiles, one should remember that in oh-so-virtuous England the age of female consent was twelve until late in the nineteenth century!)

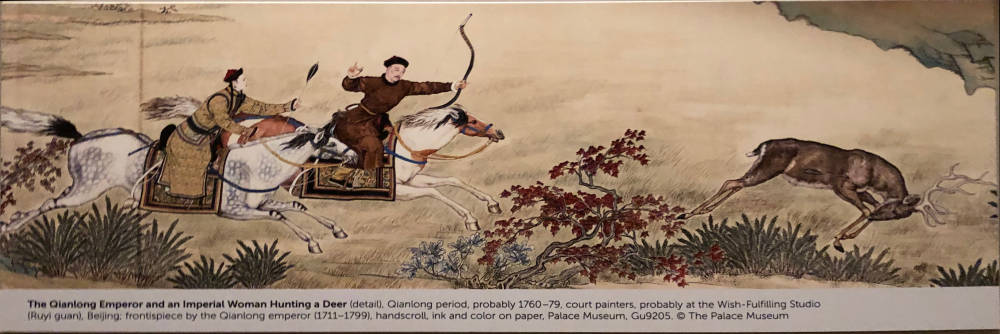

Near the beginning of the exhibition we learn that only Manchu and Mongol women could rise to become the Empress; near the very end we see why that racial or ethnic difference makes such a difference. One small display case shows the shoes or boots that the empress would wear and wear while riding horses. Empresses were not crippled women with the bound feet of the Han upper-class women. They rode horses astride (not on side-saddles like British upper-class women and royalty) and as the drawing immediately below shows, they hunted with the Emperor!

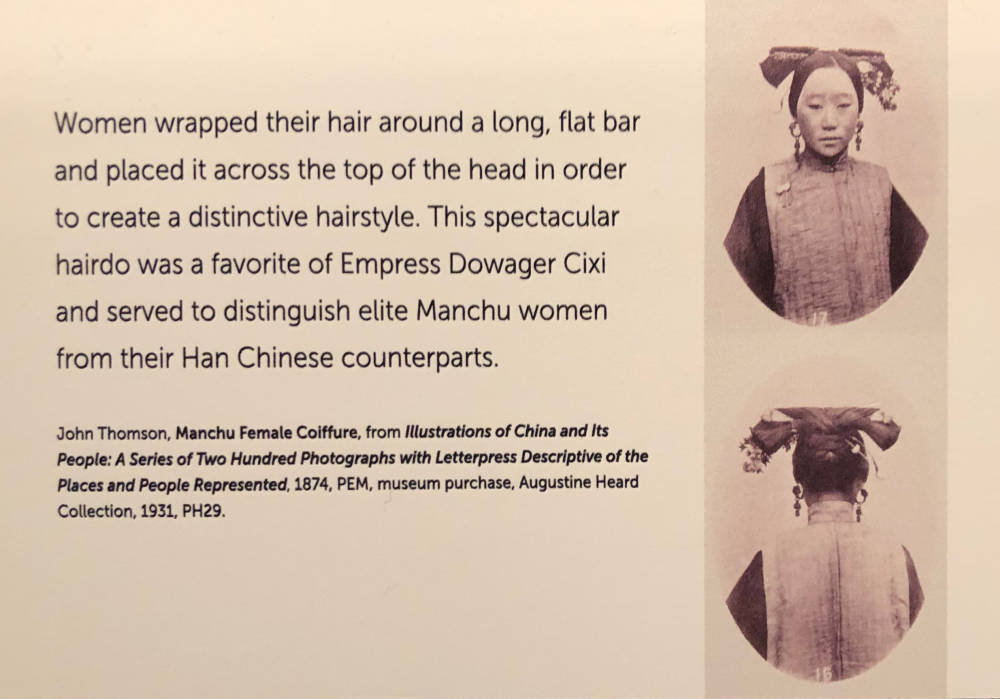

Left: The Guianlong Emperor and an Imperial Woman Hunting Deer. c. 1760-69. Here one of the Emperor’s wives races along side him and hands him an arrow. Right: Photographs from 1874 showing one of the Empress Dowager Cixi’s favorite ways of wearing her hair. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Not surprisingly, the Empresses went out of their way to distinguish themselves from the Han — or, as we would say, Chinese — women involved wearing distinguishing hair styles.

In an exhibition replete with such surprising cultural convergences and divergences one of the most expected occurs when one encounters those beautiful portraits of the empresses. The main surprise comes not , as one might expect, when the visitor discovers that they represent a true cross-cultural project — a European artist painted the empress’s face while a Chinese one created the remainder of the portrait. Rather the purpose and placement of the portrait is what most surprises, for in sharp contrast to the practice of Western regimes since ancient Rome, the image of a member of the ruling family is not intended for public consumption. The portrait, in other words, did not serve public recognition or veneration. Instead, as Daisy Yiyou Wang’s “Deciphering Portraits of Qing Empresses” explains, “All portraits of Qing empresses created for worship at the Hall of Imperial Longevity were commissioned by emperors” (98) and they could only be seen by an emperor on specific occasions. These portraits were sacred objects whose power and value remained reserved for those at the apex of power.

Equally important, and perhaps most strange is the generally unarticulated subtext that runs throughout the exhibition that rarely received any mention — namely, that these Empresses of China’s Forbidden City lived within a virtual melting pot of cross cultural influences and confluences. Given that the museum’s collection of seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century examples of such cultural exchange among Asia, Europe, and America endow it with an unusual and perhaps unique importance, the viewer is surprised to see an almost complete lack of attention to this crucial aspect of life in the Forbidden City. Italian and Bohemian artists create likenesses of Empresses, a pot for milk and tea decorated with dragons obviously derives from European designs, and an eighteenth-century ewer decorated with dragons equally obviously derived from Arab or Persian design. The designers of the exhibition have chosen to keep these objects in splendid cultural isolation.

Left: Covered bowl and plate in the imperial colors. Right: Two massive screens included in the exhibition, the one on the left composed of enormous cloisonnée panels, that on the right of embroidery.

One of the more intriguing cross cultural influences goes the other way, from the imperial court to those far from China. The yellow china cup, cover, and plate with pink and blue accents obviously employs the Imperial yellow. But when Chinese traders married Malay women in what became the British Straits Colonies, they developed their own variation on traditional Chinese ceramics, which did not use this color scheme. This mixed Chinese-Malay culture known as Peranakan used precisely these colors. Did they know their history?

A far more important influence upon the imperial court appears in its Buddhism, which arrived from India entangled with elements of Hindu belief, something apparent in the sutra cover on display (left above) two of whose panels depict Vishnu and many-limbed Kali. The exhibition’s chat labels don’t mention these interesting complexities, nor do they comment what what appears to be Sanskrit writing appears on Chinese religious objects. Once again, this odd reticence even to mention things that are not Chinese,

Of all the things left unsaid in the display of the beautiful objects in this wonderful exhibition that involving the Empresses’ power most intrigues. The visitor to Empresses of China’s Forbidden City learns that these women at times achieved great power, but what did they do with it? On what issues did they make major decisions? Almost the only clue appears near the end when the visitor learns that the Empress Cixi “embezzled” — the exhibition’s word, not mine — funds intended for the Chinese Navy to build yet another palace. Given that the Nemesis, a ship of the East India Company, easily destroyed Chinese war ships in 1842, that seems a really dreadful diversion of funds. One only has to compare the reaction of the Japanese after the visit of Admiral Perry and his black ships, a topic discussed in the Peabody Essex Museum’s permanent exhibits. The Japanese rapidly modernized to the point that in less than half a century they effortlessly destroyed almost the entire Russian fleet in a single battle whereas the Chinese government remained convinced of its godlike superiority while it became increasingly vulnerable. In other words, has history been as kind to the Empresses of China’s Forbidden City as the organizers of this exhibition?

Bibliography

Wang, Daisy Yiyou. “Deciphering Portraits of Qing Empresses.” Empresses of China’s Forbidden City, 1644-1912. Exhibition catalogue. Salem, Massachusetts: 2018.

Last modified 18 December 2018