Oh, London is a man's town, there's power in the air;

And Paris is a woman's town, with flowers in her hair;

And it's sweet to dream in Venice, and it's great to study Rome;

But when it comes to living there is no place like home.1

s an American travelling Europe, Henry Van Dyke was happy to quickly classify and characterize all of the major cities in Europe in his poem "An American in Europe." Men in the nineteenth century were supposed to be at home in the city, and scholars confidently assert Victorian men's ability to stroll across all areas of any city established their right to that city — a right denied women, social inferiors, and any number of outsiders.2 The ability to understand, inhabit, and interpret the urban environment was a key trope of middle and upper class masculinity. Middle-class men's knowledge over the city supposedly gave them a unique power.3 According to such scholarship, and some prescriptive literature of the time, with the right amount of wealth and leisure, a man should easily step into the role of the urban flâneur wherever he went — confident and in control.4

s an American travelling Europe, Henry Van Dyke was happy to quickly classify and characterize all of the major cities in Europe in his poem "An American in Europe." Men in the nineteenth century were supposed to be at home in the city, and scholars confidently assert Victorian men's ability to stroll across all areas of any city established their right to that city — a right denied women, social inferiors, and any number of outsiders.2 The ability to understand, inhabit, and interpret the urban environment was a key trope of middle and upper class masculinity. Middle-class men's knowledge over the city supposedly gave them a unique power.3 According to such scholarship, and some prescriptive literature of the time, with the right amount of wealth and leisure, a man should easily step into the role of the urban flâneur wherever he went — confident and in control.4

While there might have been some men who could confidently embrace the persona of a bold flâneur with an imperious gaze, many among even the most privileged groups could not. There were many wealthy English men who found themselves lost, confused, and alienated from city life. While the urban male was theoretically confident and self-assured, London's urban explorers were often overwhelmed by the cityscape in practice. Instead of possessing the metropolis, men found themselves possessed by it. Instead of security, the urban man found alienation in London.2 As such, it is incumbent upon scholars to look beyond an unsophisticated model of the flâneur to examine other ways that men interacted with and interpreted the city. While some men felt the need to live up to the ideal of an all-powerful urban spectator, others felt no such pressures. As such, scholars need to recognize that men's relationship to the city was far from monolithic. Even scholars eager to defend the idea of hegemonic masculinity have had to acknowledge the social relations between men are too complicated to reduce to a single "pattern of power."6

Looking beyond the flâneur, this essay examines the various ways that literary men took up the challenge of experiencing and writing about London. Lured to the challenge of such an enormous and expanding metropolis, some writers confined themselves to small spaces or hidden gems, others surrendered themselves to its chaos and confusion, while others remained constantly trying, and failing, to chart, navigate and control the city. How men responded to such challenges outlines a far more robust and complicated picture of men's relationship to the urban environment than has been previously acknowledged, and posits that any uniform picture of the confident, powerful urban man is misleading. Not only did some men not experience the city as a space of unparalleled power and access, they did not even represent it that way in their writings.

As Michel Foucault famously noted, the linkage between power and knowledge is essential, and complex; how men navigated that relationship is also key to deciphering their sense of masculinity.7 Ultimately, London's crucial charm was in its powers of seduction, to tempt men with a power and knowledge that was ultimately denied. Male writers met this challenge with a variety of responses that defy any caricature of the flâneur.

I. The Flâneur and Beyond

Forever associated with the poetry of Baudelaire, the flâneur could famously blend into a crowd and yet remain slightly aloof — he is the unobserved observer who finds meaning and poetry in city life. The chaos and change inherent in the urban scene provided entertainment for the flâneur, and his experience of the city was contained and domesticated in his writing, as he controlled a potentially disruptive urban environment. He was a "living guidebook," defined by his knowledge of the city streets, its haunts, and its amenities.8 Modern metropolitan spaces provided meaning for the flâneur in opposition to the dull and oppressive atmosphere of private domesticity.9 The privileged gaze of the flâneur translated into a sense of being truly at home in the city. And yet, while grounded in a particular space and time, the flâneur is not a historical reality per say. The flâneur is essentially "an analytic form, a narrative device, an attitude towards knowledge and its social context."10 The flâneur is most useful as a "metaphoric and methodological tool" to tease out representations and creations of masculinity, as Peter Ferry suggests.11 At first glance, it is easy to see why it has been such a popular model for historians to turn to.

Historians, literary critics, and visual theorists agree that the ability to stroll across all areas of any city established men's right to the city largely denied to women, colonial subjects, and the working classes. Wealthy English men were expected to easily step into the role of urban explorer, taking on the city as if it were their own. One guidebook from as late as 1930 even chose the title London is a Man's Town (But Women Go There) to grace its cover.13 According to Victorian gender ideals, the city was a distinctly masculine world.14 The urban habituá was a grounding image of middle class masculinity, and wandering the city was supposed to be a great pleasure. And yet actual evidence of any such untroubled mastery of the city is lacking.

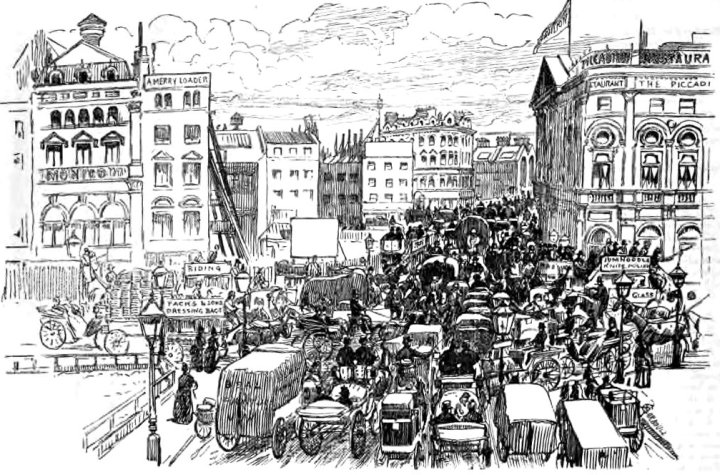

While men were supposed to feel in control of the city, in fin-de-siècle London they threatened to become overwhelmed by its masses in unsettling and emasculating ways. The world of the flâneur was a slow and silent one, and was hard to find in the frantic streets of London.15 In the English capital, one of the fundamental pillars of the flâneur was on shaky foundations — a fundamental knowledge of the city. The size of late-nineteenth-century London proved a daunting challenge. Between 1871 and 1900 the population of the city rose faster than any other provincial centre, and outstripped the national population.16 By the year 1900, 20% of the population of England and Wales lived in London.17 Even Walter Benjamin found London an unsuitable site for modernity as it was simply too crowded. This made it difficult to move throughout the city, and the crush of bodies made the ability to see one's surroundings difficult.18 Instead of actually following in the flâneur's footsteps, men in London sought out ways to reduce the city in order to consume it.19

And yet men's untroubled experience is taken for granted in contrasting women's challenges in navigating the city streets. In fact, for female writers, the opportunities available in London made it an ideal place for adventure, fortune, and even independence.20 In some respects women were freer in London than men because there were no expectations that they should thrive there or be in control. While women might have been chastised for pushing the boundaries of propriety, there was never any expectation of mastery over the city. Any bit of knowledge they gained was thus a victory. And yet where women found a site of opportunity, men found pressures and expectations. For a middle class or upper class man, London proved to be a serious challenge to the male urban identity. Unlike women, who were acknowledged to only have certain areas they were supposed to inhabit, the city as a whole was supposed to be at his command. And yet the deeply divided London landscape proved off-putting and intimidating to many London men.

The feeling of being overwhelmed by the city was a quintessentially modern problem for the late-Victorian man.21 While feeling alone in a city was nothing new, the particularities of the nineteenth-century context made the challenge more troubling. To feel helpless or powerless for a nineteenth-century man was out of keeping with dominant views of masculinity. While a man might have been allowed to be earnest and even emotional at the beginning of the century, by its close self-control and dominion over inferiors was considered requisite for any man of the middling classes or above.22 While men had a role in both the public and private spheres, it was outside the home that men were supposed to be at their most confident and competent. Men were supposed to present their most confident selves in the public sphere.23

As John Tosh notes, manhood can be acquired at maturity, but it is something that needs to be constantly shored up, in particular in public, as it is "inseparable from peer recognition, which in turn depends on performance in the social sphere."24 Thus how men presented themselves in the public sphere, and their mastery of the urban scene, was important to their sense of identity and self worth. And yet London offered a frightening aspect to both the newcomer and the native alike. As such a large and ungovernable mass, to know or feel in control of the whole of London seemed an almost impossible dream. And yet the desire to know this unknowable city persisted, and men sought to navigate their identities within the urban metropolis.

As researchers continue to expand research into masculinity, it is clear that gender is far more complicated than simple binaries of men vs. women. There is no single kind of masculinity, and masculinity can be as much about comparing oneself to other men as to women.25 And concepts of manhood and masculinity were played out in numerous arenas in the public and private spheres. Yet current accounts of men's relationship to the city often lack complexity, largely because scholarship has often focussed more on women's complicated and contested experiences, leaving men's less developed.26 The gap between prescriptive literature and experiences is wider, and more complex, than credited. And while it is difficult to peer into the hearts and minds of Victorian men, it is possible to get hints of the distance between ideals and reality, in particular in looking at literature that directly reflects on urban life.

Men wrote about London in countless ways, in fiction, in government reports, and in tourist guides. In 1884, H.F. Lester noted in "The Tourist of the Guide-Book," there was a real desire for literature that went beyond the guidebook to record the poetry and colour of the city.27 The demand for this kind of literature came from several different kinds of readers, such as tourists who did not want to look like tourists, long-time residents and lovers of the city and its history, and armchair tourists who just wanted to read about London. Just as guidebooks can tell us much about popular understandings of other spaces and urban environments, so too can more literary works.28 Travel literature in general is a Rorschach test, and tells more about the traveller than the actual space.29

Examining the genre of male urban writing, charting the experiences and writings of a selection of middle and upper class men, opens up a wide-ranging picture of their relationship to the city. While some men exuded confidence and nonchalance, others openly expressed fears and anxiety, while others simply retreated to smaller, more familiar spaces. The rest of this article explores male reactions to the city as both strangers to the city, and as purported experts. While approaching the city from different perspectives, the writers all share the problem of how to explore, understand, and translate London to an outside reader. As virtual tour-guides, their texts show that their perceptions were far more diverse than the all-seeing gaze of the flâneur. The tourist or new resident to the city allowed himself the flexibility of not knowing the city, while gaining confidence with every new discovery. The local expert could claim absolute knowledge of the hidden treasures, or a very small place. And the historical escapist found the modern city too large and unknowable, instead engaging in nostalgia for another time.

II. Visiting London

To know the city was a challenge, but for a visitor to the city, the prospect seemed all the more daunting. To the Londoner W. J. Loftie, not only could a traveller never understand the English capital, he could not even understand its basic outlines: "The foreigner cannot, in a short visit, form any idea of the size of London."30 Loftie believed that any true understanding of a city was steeped in personal memories and an appreciation of the collective memory of that place and space. A visitor simply could never have the history to acquire such memory. Even Yoshio Markino, a Japanese watercolour artist who spent forty years in London felt its size was the most daunting boundary he could not overcome. "I have found out it is larger than any other town. London is on the extremely larger scale altogether. She is just like a vast ocean where sardines as well as whales are living together."31 Instead of understanding the modern city as a site of "male subjective desire" over an imagined feminized sexual object, London threatened to overwhelm male visitors.

Not only could a visitor never claim full knowledge of the city, he would always stand out from the crowd. This included not only racialized difference such as Markino and imperial travellers experienced, but even a traveller from the English countryside "...is instantly to be detected."33 To be a foreigner in a sense is to be ridiculous, and to be conspicuous in a crowd; such a man could never even attempt to take on the mantle of the flââneur, nor could he experience the city in a genuine way. Manhood was a problematic category, a prize that had to be won again and again, and London seemed to defeat that goal.34

For many travellers and new residents to London, the city seemed a threatening space. While Henry James eventually became a London habitué, when he first arrived in the city he found it overwhelming. "It is a kind of humiliation in a great city not to know where you are going."35 Being lost in a city is always a disorienting affair, but for a man in the late-nineteenth century, it was a blow to his manhood, placing him firmly outside the role of the confident urban explorer. For James, this led to an initial hatred of the city that made him fearful to leave his rooms:

London was hideous, vicious, cruel, and above all overwhelming... [I] would rather even starve, than sally forth into the infernal town, where the natural fate of an obscure stranger would be to be trampled to death in Piccadilly and have his carcass thrown into the Thames.36

James's admission was surprisingly frank, and yet his feelings were not isolated. The dangers of anonymity were a constant refrain in visitors' impressions of London.

Another American visiting the capital, Richard Grant White, tried to overcome his ignorance of the city by walking its streets, so often recommended by mass-produced guidebooks. And yet he did not find these experiences let him be more in touch with the city or its inhabitants. In fact:

I never felt so lonely as I did in these solitary rambles in London, — never so much cut off from my family and my home, I may almost say from humankind. In mid-ocean I did not feel so far removed from living contact with the world ... I could not take in even London; and what was out of London was beyond beyond.37

Above all it is a sense of being overwhelmed that is almost palpable in such descriptions. While White would later boast that he in fact had succeeded in learning the city and blending in like the locals, he betrays this latter confidence several times.

White eventually presents an account of his experiences of London that is both marked by judgemental arrogance, and undercut by anxiety. He comes to assert his own knowledge of London only at the expense of critiquing native Londoners. He was astounded by Londoners'

... actual ignorance of their own neighbourhoods, of the principal streets, great thoroughfares, and public places. The very cabmen were not to be trusted; and I had to set one right when I had been in London only a fortnight. I found that it was much better to trust to my own general knowledge, and to my feeling for form and distance, than to ask direction form any one but a policeman.38

Not only does he claim to now be at home in the city after two months, he finds himself directing local cabmen and admits the policeman as his only potential rival for knowledge. His only experience of getting lost he justifies by the fact that it was after midnight, and that he trusted other people's directions rather than his own instincts.39 This posturing stance very much ties into Michael Kimmel's notion of masculinity as "a defence against the perceived threat of humiliation and emasculation in the eyes of other men."40 White attempts the model of natural expert to justify his position in the city.

Self-castigation for relying on exterior help or typical patterns was a common trope of London visitors. And the foreigner-as-native persona evolved with certain key criteria. Such a man did not come with guidebooks, but perhaps a map at most. He did not stay in the "tourist" hotels, but instead found his own lodgings in the city. One such would-be native, American essayist E. S. Nadal, explained his mistakes as he detailed his first experience in the city:

The night of my arrival in London I stopped at a hotel not far from Westminster... It was one of those large hotels to which people go who know nothing about London, and I had dined in a hushed and stately dining-hall instead of the dingy little coffee-room one should always seek.41

Nadal made the "mistake" of staying at a central, well-appointed hotel and enjoying the comforts of its beautiful dining facilities. Such experiences might have been convenient, but they were not "authentic." It was only in the little-known holes in the wall that a man could proclaim his native status and hope to escape the humiliation of being labelled a tourist. And it is a long-established truth that the most vocal critics of tourists are tourists themselves.42

Perhaps most remarkable about such accounts is they were completely ignorant of their ironic position. Here were men who derided relying on travel guides producing their own travel narratives. In one sense they could act as a stand in for those with no intention of travelling to London — a guide for how they would have acted in the city without having to go there. But more practically, they were also useful for the man travelling to the city so that he, in turn, could take on the persona of the foreign/local man. And yet the writers maintained power through these writings; if their readers did not become experts or experience the city in the same authentic way, their own superior status was reinforced. This seems to be the closest most men came to embracing the ideal of the flâneur — reinforcing the desire to know the city, and setting themselves as more expert than their readership.

Even if a man could claim familiarity with the streets of the city, its basic pathways and some little known secrets, for the middle and upper class traveller, conquering the geography was only half the battle. Equally, if not more important, was to understand the people of London. London certainly had rivals in terms of the beauty of its architecture or the fashion of its dress, but it was the people of London, and how they interacted, that made it so fascinating to visitors.43 And yet to understand the English social world was not an easy task. Americans in particular were sometimes affronted by the reserve of London society, and were surprised that they displayed no real curiosity about their transatlantic neighbours. While admitting that they were not unkind to foreigners, E. S. Nadal did feel that in meeting a new acquaintance, "They hold back till they are sure, not that he is virtuous, but that it will help them to know him."44 English reserve is thus transformed into a form of snobbish self-interest.

Other authors rejected any attempt towards mastery of the city or its people, and accepted the role as helpless visitor. This is the kind of experience usually described as the preserve of women or colonial subjects. Indian tourists who flowed into London after the Indian and Colonial Exhibition of 1886 could never be anonymous members of the crowd, and yet they explored the city and its people, not content to remain solely the objects of the domestic imperial gaze.45 One of the defining characteristics of the New Woman was the ability to travel across the city exploring public transit and doing away with chaperones.46 Women's entrance into traditional male spaces has been noted as the cause of endless public debates.46 And yet these experiences are often posited against an imagined male mastery of the city. Perhaps the relationship is less a dichotomy than a spectrum of experience.

And not all men accepted the association between being lost in the city and being less of a man. Some men claimed no more mastery or power over the city than women or colonial visitors. Even for the most "manly" of Victorian men, African big game hunters, the challenge of London was more than they could take. The often-comical representations of these intrepid explorers lost and overwhelmed in the city did not question their manliness, but rather questioned the valorisation of urban life.48 The American author William Dean Howells took a novel approach to London in his text London Films where he looks at the city as if through a Kodak lens, comparing it to his native New York.49 And yet his expansive, poetic descriptions of the buildings, the people, the crowds throughout the city are entrancing, do not claim any control of the city. Rather, Howells is swept along by it:

You are now a molecule of that vast organism, as you sit under your umbrella on your omnibus-top, with the public waterproof apron across your knees, and feel in supreme degree the insensate exultation of being part of the largest thing of its kind in the world, or perhaps the universe.50

Far from the omnipotence of the flâneur, Howell is content to be a more passive spectator, caught up in the power and splendour of London without any temptation to master the metropolis. Here is a man rejecting any idea that to give oneself up to the unknown is emasculating, and he rejects the idea of absolute knowledge being possible or even desirable.

III. London in miniscule

For visitors or new residents to London, they might not have gained a sense of security or control in the city, however they could also easily lower expectations because of their outsider status. Native residents both had more access, and equally more pressure. Despite some overanxious foreigners' remarks that Londoners were the least likely to understand their city, there was a strong tradition of urban exploration and description by its most stalwart residents. By the second half of the nineteenth century, however, few asserted the guise of flâneur. Instead, many men admitted their limitations and were happy to break the city down into easily comprehendible chunks. A number of works were produced that described certain areas or neighbourhoods of the city, without attempting the whole. While a man might never know London, he could at least claim mastery over his own neighbourhood.

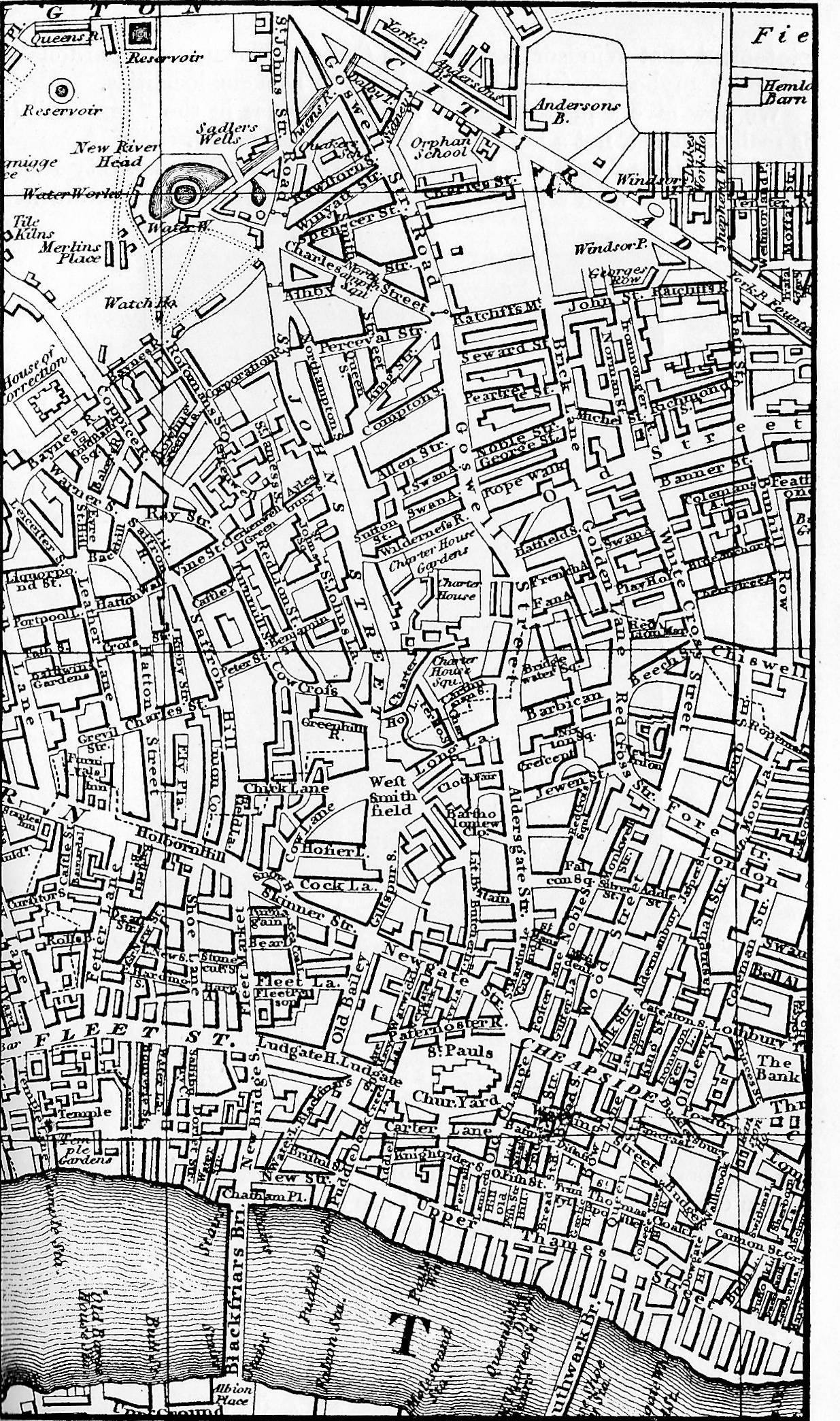

An initial acknowledgement of failure was a common idiom. Most authors had to eventually acknowledge to the fact that the city was so large that it was inherently beyond the limits of their knowledge. E.V. Lucas, a self-proclaimed "wanderer," found that there was not only no place to begin, but no place to end. Even a thousand books on London he felt would not get at every aspect of the place.51 Augustus Hare published a detailed two-volume work describing various walks in London including comprehensive paths and full histories for each journey. Yet he had to admit that it was becoming impossible to cover the whole city. To be a true expert of the city was a lost art perhaps never to be recaptured: "Macaulay had the reputation of having walked through every street of the London of his day; but if we consider the ever-growing size of the town, we cannot believe that any one else will ever do so."52 To emphasize his point, Hare then noted that the population of London outstripped the nations of Denmark and Switzerland, doubled the population of Paris and was thrice that of New York. In acknowledging his limitations, Hare was careful to justify the reasons for this weakness. Men could thus only demonstrate mastery within limits.

Just as some foreigners expounded their own knowledge at the expense of others, London writers suspected that many barely knew the city that they called their home. Visitors were not the only observers to note that locals did not know London as they should:

Scarcely any man in what is usually called "society" has the slightest idea of what there is to be seen in his own great metropolis, because he never looks, or still more, perhaps, because he never inquires.... Strangers also, especially foreigners, who come perhaps with the very object of seeing London, are inclined to judge it by its general aspects, and do not stay long enough to find out its more hidden resources.53

Admitting how little most Londoners understood their own city was the first step in opening the door to the utter unknowability of the city. Even familiar childhood memories faded when confronted with a constantly changing city.54 To attempt to understand London was a never-ending task.

Many authors could only find meaning in London's past. J. Ewing Ritchie's text, About London, goes back to the time of the War of the Roses to find the origins of everything best about London society.55 The truth of London seemed to be found in centuries past. Laurence Gomme seemed to agree; his London states that the only way to understand modern London, and England, was to understand its beginnings. And the reason for such exploration lie in the fact that London is best understood as a living museum — its very buildings, monuments, and passageways tell a truth to future generations.56 To Gomme and other antiquarians, understanding the history of London is the best way to seek out its current truth and its future as: "history is a living force not a dead record."57

Even a book that began with an ostensibly modern aesthetic — another trip aboard the railway—could very quickly become a history lesson. To G. K. Chesterton every railway station turned his mind to London's history: "Crowded and noisy as it is, here is something shy about London: it is full of secrets and anomalies; and it does not like to be asked what it is for. In this, there is not a little of its history as a sort of half-rebel through so many centuries."58 While abandoning the ideal of total mastery over the current city, in some ways these stories do declare knowledge over the city in particularly powerful ways. By seeing the city through a more historical and academic point of view, the city becomes something to deconstruct, research, and possess through learning. These men assert their power and knowledge over the city in less experiential, and more bookish ways.

Others are more explicit that they turn to London's past because they find it superior to its present. Donald Shaw found the early twentieth century far inferior in not only its material aspect, but also in its people. Instead of "solid silver spoons and a higher type of humanity" he found only "electro-plate and the shabby-genteel masher."59 It is no surprise he situated his meditation on London almost a half century earlier. This was a trend that would only increase after the end of the First World War, when nostalgia for a golden age of London was rampant. Yet a work looking wistfully back on London such as James Bone's The London Perambulator could not choose which historical London was best. In walking along St. James's Street and Pall Mall he quickly jumps from the Tudor period to Pepys' London.60 In these ways the antiquarian asserted another form of male mastery over the city. If the flâneur's all-seeing gaze was beyond them, they could demonstrate knowledge of the history and legacy of historical London. And emphasizing the depth and complexity of London's history makes it a greater accomplishment to sort through and rationalize it all.

Authors had to admit that to know London in its entirety was an unreachable goal in the modern age. E. V. Lucas found that there was not even a single London to understand. Instead he likened the capital to a nation in and of itself, containing many towns and villages within it. The capital of this country was the heart of London where the restaurants, shops, music halls, theatres, and architectural monuments were located. This was the showpiece of this country and what most visitors came to see. But it was only a tiny fraction of the whole, and for many Londoners, had no relation to their everyday lives and experiences. Most kept to their own villages and rarely left their small, prescribed spheres.61

For most of the authors of such works, their prescribed sphere was the West End of London. A belief in the centrality of the West End could sometimes extend to ignoring the rest of the city entirely. Though the heart of the West End was home to very few, it symbolized to many all that was best about the metropolis; not only the upper, but also the middle classes, looked to the West End as the heart of London. During the summer, when the wealthy social elites fled the city by the first week of August, authors referred to the city as "empty," despite the fact that millions of people still filled the capital. It was only the most prominent edifices of the West End that were left empty, and the rest of the city would have remained busy with activity. While the West End might have held the most impressive sights of the capital, it was nowhere near its entirety. The city was diverse, its residents were highly segregated and thus understanding the city would have been beyond many of its habitués.62 For many, the boundaries of the West End were as far as their knowledge of their city extended. These men's constrained, restricted vision of London hardly live up to the flâneurial ideal. Instead of confident urban explorers, they stuck to familiar spaces and safe neighbourhoods.

More adventuresome writers set their pens to uncovering the unknown or secreted delights of a familiar metropolis. Fred Lane's series of articles for The English Illustrated Magazine focussed on the hidden romance of new places and perspectives. He was particularly taken with the life of the rails, and spent a day riding around on various underground trains to get a new outlook of the city. He also spent time examining the various railway stations of the city, and not only described the buildings, but recommended when and how to view each site. While St. Pancras might not be striking at first glance, he wrote in "London Railway Stations" that one must go to the Midland terminus when no trains were leaving, at night, walk along to the back of the third platform in order to get the best impression of the station which only then appears like a temple.63 He also recommends walking about the city when the public houses are shut, between twelve-thirty and five in the morning. It is here that the real nightlife of the city comes alive. And he warns "In the Small Hours" that while people assume the city is asleep, in fact:

The sleep is more apparent than real, however, for so varied are the occupations and pleasures of the inhabitants of this modern Babylon, that it is well-nigh impossible to pass through any important thoroughfare, no matter what the hour, without encountering some of one's fellow-men.64

The native of the city has the opportunity to learn the most interesting moments of the city over time, and to uncover what places or moments are most overlooked. As such, these visions of the city are authoritarian and confident, demonstrating knowledge built over a number of years. And yet these descriptions of the city are deliberately episodic and incomplete.

Similarly, H.D. Lowry wrote a series of five articles for the Windsor Magazine detailing various parts of "Unknown London." In his first outing Lowry takes his readers to Walworth Road in Southwark, a place his readers could easily describe as an "English Hades."65 And while he cautions readers to look deeper to find the community spirit of the place, he is still happy to leave the crowded and chaotic borough. His next trip to the London docks is pitched as a world of adventure, opening up the British Empire and the world through the intense dockside activity. At the West India Docks the author admits to a desire to travel, yet acknowledges he is "filled with regrets that he has not the spirit to act up to his boyish resolves and enlist, though it were but as a cabin-boy, in the glorious comradeship of men that go down to the sea in ships."66 His last articles cover the Italian community at Saffron Hill, community charity concerts, and the Inns of Court67. These stories glimpse into only unknown places and communities, and leave as many questions as answers for both the reader and writer. The impression the series as a whole leaves is that there are as many stories in London as one could possibly imagine, and it would be impossible to visit or understand them all.

Conclusion

To understand London proved an elusive goal that the honest observer had to admit he fell short of. For the native or long-term resident of the city, London proved a daunting space, and outlining its history or dissecting it into its disparate parts proved a way to ignore the unknown and unknowable. The tourist found himself faced with the more difficult task, as he was a stranger in the largest city in the world. And the tactic of overcompensating for their inadequacies by pointing out the lack of Londoners' own knowledge of their cities was a poor substitute for real knowledge of the metropolis. Yet in being a local, knowledge of the city should have been implicit and its lack was more galling than that of a foreigner.

While men could explain the key sights of the city on the most basic level, this knowledge did not allow these men to feel truly at ease in their positions as urban spectators. London was such a giant that instead of power and certainty, men found only mysteries and unrealised expectations. In exploring the relationship between affluent men and the city, it is clear that while some men struggled to live up to the Parisian model of the flâneur, most conceded it did not fit the realities of London. Nor are the three alternatives presented here the only possibilities, as the East End pleasure seeker and the mission-guided charity workers had their own alternative stories to tell. Much work needs still remains to be done in understanding the gendered nature of the city that defied simple binaries. What is clear from this study is that male experiences with the city are far more diverse and complicated that current narratives state. Historians have done such admirable work exploring women's entries into the public sphere and how they created new opportunities for themselves in the city; however, this should not be done at the expense of abridging men's experiences. London men found the ideal of the confident urban explorer to be a role they were often drawn to, and yet not one that was comfortably achieved.

Last modified 21 May 2014