he British had been fond of "Colchester Natives" since

Roman times, when barrels of oysters from the remote corner of the Empire were highly

prized in Rome. When the legions pulled out in 410 A. D., the oyster farms were

abandoned, and oysters disappeared from British recipes until the reign of King Richard

the Second. Since meat was prohibited by the mediaeval church for up to one-third of the

year, oysters were a popular alternative to fish, although the mixing of oysters with

such meat dishes as steak-and-kidney pie (using stout and dropping the kidneys), steak,

and roasted mutton occurred after the

Reformation. Since beef-and-oyster pie was a classic Victorian dish, demand for the

shellfish was high in nineteenth-century Britain: "as many as 80 million oysters a year

being transported from Whitstable's nutrient-rich waters to London's Billingsgate Market

alone" (Ysewijn). Although in Pickwick Papers the aphoristic

Sam Weller observes that "Poverty and oysters always seem to go together" (a notion that

Dickens would have derived as a child in Rochester and Chatham), by mid-century the native oyster beds were becoming exhausted, and the price of oysters was rising to such an extent that only the prosperous classes could afford to eat them "on the shell" by mid-century. Still a cheap source of protein, six oysters could still be used by poorer Londoners as the basis for the traditional pie with a suet crust, a pound of inferior steak, onions and carrots, and a rich sauce based on a pint of porter or stout.

he British had been fond of "Colchester Natives" since

Roman times, when barrels of oysters from the remote corner of the Empire were highly

prized in Rome. When the legions pulled out in 410 A. D., the oyster farms were

abandoned, and oysters disappeared from British recipes until the reign of King Richard

the Second. Since meat was prohibited by the mediaeval church for up to one-third of the

year, oysters were a popular alternative to fish, although the mixing of oysters with

such meat dishes as steak-and-kidney pie (using stout and dropping the kidneys), steak,

and roasted mutton occurred after the

Reformation. Since beef-and-oyster pie was a classic Victorian dish, demand for the

shellfish was high in nineteenth-century Britain: "as many as 80 million oysters a year

being transported from Whitstable's nutrient-rich waters to London's Billingsgate Market

alone" (Ysewijn). Although in Pickwick Papers the aphoristic

Sam Weller observes that "Poverty and oysters always seem to go together" (a notion that

Dickens would have derived as a child in Rochester and Chatham), by mid-century the native oyster beds were becoming exhausted, and the price of oysters was rising to such an extent that only the prosperous classes could afford to eat them "on the shell" by mid-century. Still a cheap source of protein, six oysters could still be used by poorer Londoners as the basis for the traditional pie with a suet crust, a pound of inferior steak, onions and carrots, and a rich sauce based on a pint of porter or stout.

Edmund Yates on London Oyster Houses

Those were the days of supper, for at that time a beneficent Legislature had not ordained that, at a certain hour, no matter how soberly we may be enjoying ourselves in a house of public entertainment, we were to be turned into the streets. There were many houses which combined a supper with a dinner business; there were some which only took down their shutters when ordinary hard-working people were going to bed. Among the former were the oyster-shops — Quinn's in the Haymarket; Scott's, facing that broad-awake thoroughfare; a little house (name forgotten) in Ryder Street — not Wilton, who closed at twelve; Godwin's, with the celebrated Charlotte as its attendant Hebe, in the Strand near St. Mary's Church. Godwin's was occasionally patronized by journalists and senators who lived in the Temple precincts: the beaming face of Morgan John O'Connell was frequently to be seen there; and Douglas Jerrold would sometimes look in. Charlotte was supposed to be one of the few who had ever silenced the great wit: he had been asking for some time for a glass of brandy-and-water; and when at length Charlotte placed before him the steaming jorum, she said, "There it is, you troublesome little man; mind you don't fall into it and drown yourself." Jerrold, who was very sensitive to any remarks upon his small and bent figure, collapsed.

Other famous oyster-houses of that day, as they are of this, were Lynn's in Fleet Street, Pimm's in the Poultry, and Sweeting's in Cheapside; but they were all closed at night. Restaurants where the presence of ladies at supper was encouraged rather than objected to were the Café de l'Europe, in the large room at the back (the front room, entered immediately from the street, was reserved for gentlemen, and will be mentioned elsewhere), and Dubourg's, already mentioned, the proprietor of which —a fat elderly Frenchman, his portly presence much girt with gold watch-chain — was a constant attendant at the Opera, and was well known to the rouésof the day.

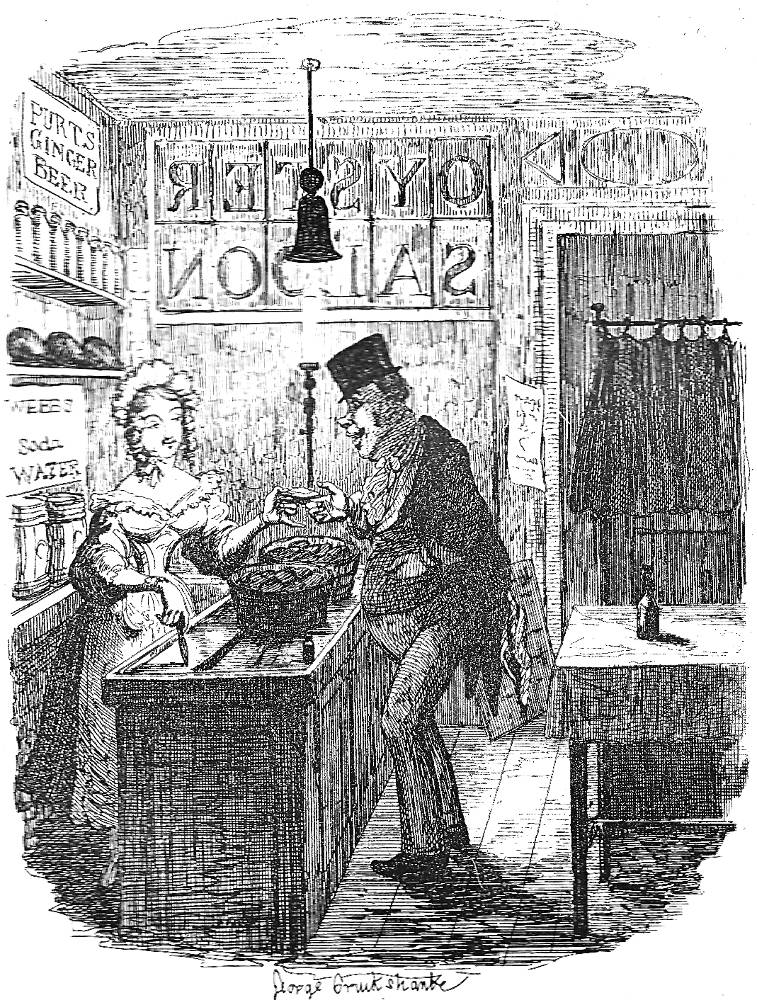

Dickens’s Mr. Dounce comes upon a new oyster shop

Two illustrations of Mr. Dounce in an oyster shop. Left: Mr. John Dounce in the Oyster Shop. George Cruikshank. Right: Misplaced Attachment of Mr. John Dounce. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Shops of all kinds appear in Dickens's fiction and journalism, most famously the old curiosity shop in the novel of the same name, although he seems to have been chiefly interested in inns, hotels, public-houses, and bake-shops. Nevertheless, he had a fondness for oysters throughout his life; on his second American tour, for example, his repast on the night of a public reading would consist solely of champagne and oysters. In the following passage, Dickens’s character comes upon a new oyster shop and the pretty salesgirl inside:

Mr. John Dounce was returning one night . . . to his residence in Cursitor-street . . . when his eyes rested on a newly-opened oyster-shop, on a magnificent scale, with natives laid, one deep, in circular marble basins in the windows, together with little round barrels of oysters directed to Lords and Baronets, and Colonels and Captains, in every part of the habitable globe.

Behind the natives were the barrels, and behind the barrels was a young lady of about five-and-twenty, all in blue, and all alone. . . . He entered the shop. — "The Misplaced Attachment of Mr. John Dounce," pp. 183-84.

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. "The Misplaced Attachment of Mr. John Dounce," Chapter 7 in "Characters," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 181-185.

Dickens, Charles. "The Misplaced Attachment of Mr. John Dounce," Chapter 7 in "Characters," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. I, 232-38.

Yates, Edmund. "1847-1852." His Recollections and Experiences.London, 1885. Rpt. in "Victorian London — Food and Drink — Restaurants — Oyster-shops and restaurants."Dirty Old London. New Haven: Yale U. P., 2014. Victorian London. Web. 11 April 2017.

Ysewijn, Regula. "Poverty and Oysters." Food Wise. Web. 11 April 2017.

Last modified 17 May 2017