Photographs kindly contributed by English Heritage, Apsley House, for use in this review. If you wish to reproduce any of the images, you need to contact English Heritage. For opening times and other special events at Apsley House, please see (offsite) its own very informative website. Click on all the images below to enlarge them, and on the first one for more information about the house itself.

Apsley House [Click on these and the following images to enlarge them].

Once popularly known as "Number 1, London," Apsley House at Hyde Park Corner is unique. The first Duke of Wellington bought it from his eldest brother as his London seat, and had the original Robert Adam house extended and remodelled at huge cost in the early nineteenth century by members of the Wyatt dynasty of architects: first James Wyatt, and then James's eldest son Benjamin Dean Wyatt, helped by the youngest son, Philip Wyatt. With its public rooms now open to visitors under the auspices of English Heritage, the Duke of Wellington's house is a fantastic place to visit at any time — but especially now, during the "Young Wellington in India" exhibition.

The first surprise for any new visitor is undoubtedly Antonio Canova's huge nude statue of Napoleon looming beside the stairwell. The famous Italian sculptor had depicted not the military commander who was, in fact, of quite average height, but the heroic figure whose presence towered over the world during the Napoleonic wars. This was the giant that the first Duke of Wellington felled at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. The grand staircase itself leads to some of the most beautifully decorated rooms in all London. This looks inviting: but the first stop at present should be the Basement Gallery, where, at least until early November 2019, visitors will get some insight into how the Duke first learned his military skills, and earned his stripes — not in revolutionary Europe but much further away, in India.

The Basement Gallery

Left: The Basement Gallery at the exhibition (shared, with permission, from the Apsley House Facebook account). Right: A portrait of the young Wellington by John Hoppner (1758-1810), painted in 1795, just before he left for India (© Stratfield Saye Preservation Trust).

All is explained here in an attractively laid out exhibition space. A parade featuring caparisoned elephants makes a frieze above a series of information panels and illustrations. Step into this exotic world, and you discover that in 1793 Richard, Marquess Wellesey (1760–1842) bought his second younger brother Arthur a commission as major in the 33rd foot. Arthur had previously been with several other regiments, but had never actually seen any active service. His first expedition with the 33rd was a disappointing spell in the Netherlands, when the regiment had tried unsuccessfully to check French incursions. His next posting, however, was to India. Still aged only 27, the young major embarked for Fort William in Calcutta in 1795, taking with him plenty of reading material for the long voyage.

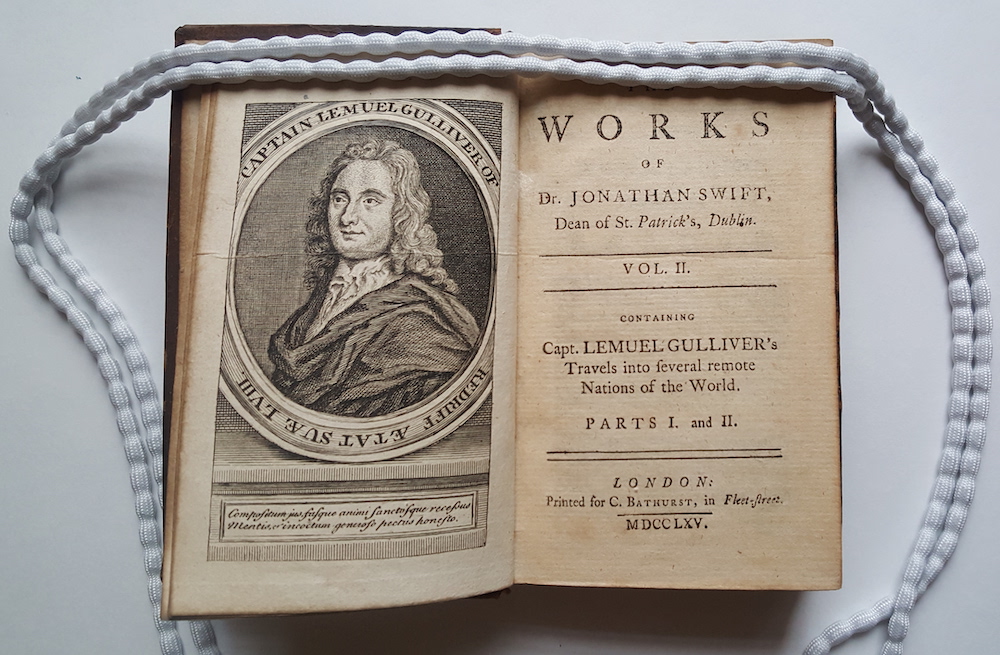

This copy of Swift's Gulliver's Travels, which Wellington took with him in his "travelling library" of 200 volumes, is one of the books on display (© Stratfield Saye Preservation Trust).

Richard himself, then known as Lord Mornington, arrived in India in 1798 as the Governor-General of Bengal. This was the point at which Arthur followed his brother's adoption of the spelling "Wellesley" for his own surname. Naturally, most accounts of the period here focus on the older brother, described in one source as an "uncompromising empire-builder" (Keay 309). All the same, Arthur was already winning his spurs, and becoming known as an able tactician. His successes were key to helping his brother realise his ambitions. He won his first major victories in India, first by storming Seringapatam and inflicting huge losses during the Fourth Mysore War of 1799, and then by defeating the Mahrattas in the more challenging Battle of Assaye in 1803. He later declared that this last battle was the hardest one he ever fought, harder even than Waterloo: in this context Christopher Hibbert adds that he conducted it "with energy, skill and much bravery"(43). Both these victories helped establish the East India Company's control over large parts of the subcontinent, laying the foundations for Britain's imperial rule.

A portrait of Wellington by Robert Home, c. 1804, right at the end of his time in India (© Stratfield Saye Preservation Trust).

Of particular note in this gallery is a cabinet with relics of the defeat of Tipu Sultan, including a large, evil-looking sword, and a short, equally lethal dagger. However elaborately decorated, such reminders of battle may not please everyone. To the British, Tipu was "the Company's best organized and most resolute foe" (Spear 102-03); to his fellow-contrymen, though, he was a hero who fought hard, was out-manoeuvred, and fell while fighting with astonishing bravery. However, this section tells much not only about the young Wellesey's tactical skills in battle, but also about his subsequent behaviour: after taking over, he issued orders to stop the plundering and violence towards civilians, and spent three years in Mysore, thoroughly re-organising its administration. Today, this seems as much to his credit as his leadership qualities in battle.

A portrait of Mrs Isabella Freese, with whom he fell in love, by Thomas Hickey (© Stratfield Saye Preservation Trust).

Particularly welcome in this connection are the insights into his personal qualities and private life — including his liaison with Mrs Isabella Freese, the wife of a Captain in the artillery, whose portrait is also on display: there is much evidence that during these busy and dangerous years he found time for romance, and even fathered a child by her (see for example Muir, The Path to Victory, 102-03). However scandalous the affair, it ended amicably, and Wellesley fulfilled his responsibilities towards the boy (also called Arthur) in his role as godparent. He seems to have excelled in mopping-up operations.

The Waterloo Gallery

The Deccan dinner service, bought for Wellington by his fellow officers, and presented to him in 1807 (© Tracy Jones).

Exhibition items are displayed elsewhere in the house as well, so it is essential to continue the tour by mounting Benjamin Dean Wyatt's staircase (or going up by lift) and exploring the rich interiors and artworks on the first floor. Usually the hightlights would be the paintings by Velásquez, Goya and others, many of which were gifted to the Duke of Wellington by the King of Spain after the Battle of Vitoria in northern Spain. But the highlight at this time is an early gift from his officers in India, the gleaming Deccan dinner service laid out now in the fabulous Waterloo Gallery. On 28 September, when Wellesley was about to embark for England again, the other officers had gathered to decide how to express their gratitude to their commanding officer, and this was what they came up with. Interestingly, it was bought in England — that must be another story. At any rate, the splendid set would be presented to him in 1807, when it had been augmented by cutlery from Napoleon's carriage, some of it bearing his imperial crest.

Left: Two large tureens and a sauce tureen from the dinner service (© Stratfield Saye Preservation Trust). Right: The present Duke of Wellington at Apsley House (© Simon Ford Photography).

There is, of course, much more to see in this house: you may even catch a glimpse of the present Duke of Wellington, who sometimes comes to look again into what is, for him, a very special kind of family album. But when his most famous forebear looked ahead, he could not have imagined all this. When Major-General Wellesey left Calcutta, his real glory days lay ahead: the Battle of Waterloo remained to be fought, and his life as a politician had yet to unfold — his difficult marriage, too. Nor could he have foreseen that this eventful life of his would be commemorated after his death in so many ways, including a towering monument in the north nave of St Paul's, where he would be buried with enormous pomp and ceremony.

Portrait of Wellington by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1818, painted after the victory at Waterloo (© Stratfield Saye Preservation Trust).

But as his ship set sail for England again, he was in many ways a new man, confident and extremely able in command, and ready for the stiffest of challenges. His time in India had helped to secure an empire, which arguably had advantages as well as disadvantages for the subcontinent. His defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo, which would herald a long period of relative calm in Europe, is rightly celebrated to this day. Don't miss this valuable introduction to his life at Apsley House.

Bibliography

Keay, John. A History of India. Paperback ed. London: Harper Collins, 2001.

Spear, Percival. A History of India. Vol. 2. Rev. ed. London: Penguin, 1978.

"Young Wellington in India" (Exhibition Press Release).

Muir, Percy. Wellington: The Path to Victory. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

Muir, Percy. Wellington: Waterloo and the Fortunes of Peace. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015.

Created 12 June 2019