usical comedy, a genre that developed alongside the final Savoy operas in the 1890s, has been neglected in cultural history and has disappeared from stage performance. While countless books have been written on the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan, it was not until 2004 that Len Platt published the first academic book that focused on musical comedy.1 Since then, other work has appeared revealing the successful transfer of British musical comedy to stages in continental Europe.2 However, serious studies of this genre remain small in number, and I hope to stimulate interest today that might lead to future research. Among the many reasons for such research is that we cannot fully understand the development of the stage musical without a knowledge of musical comedies, especially since so many of them transferred successfully to Broadway.

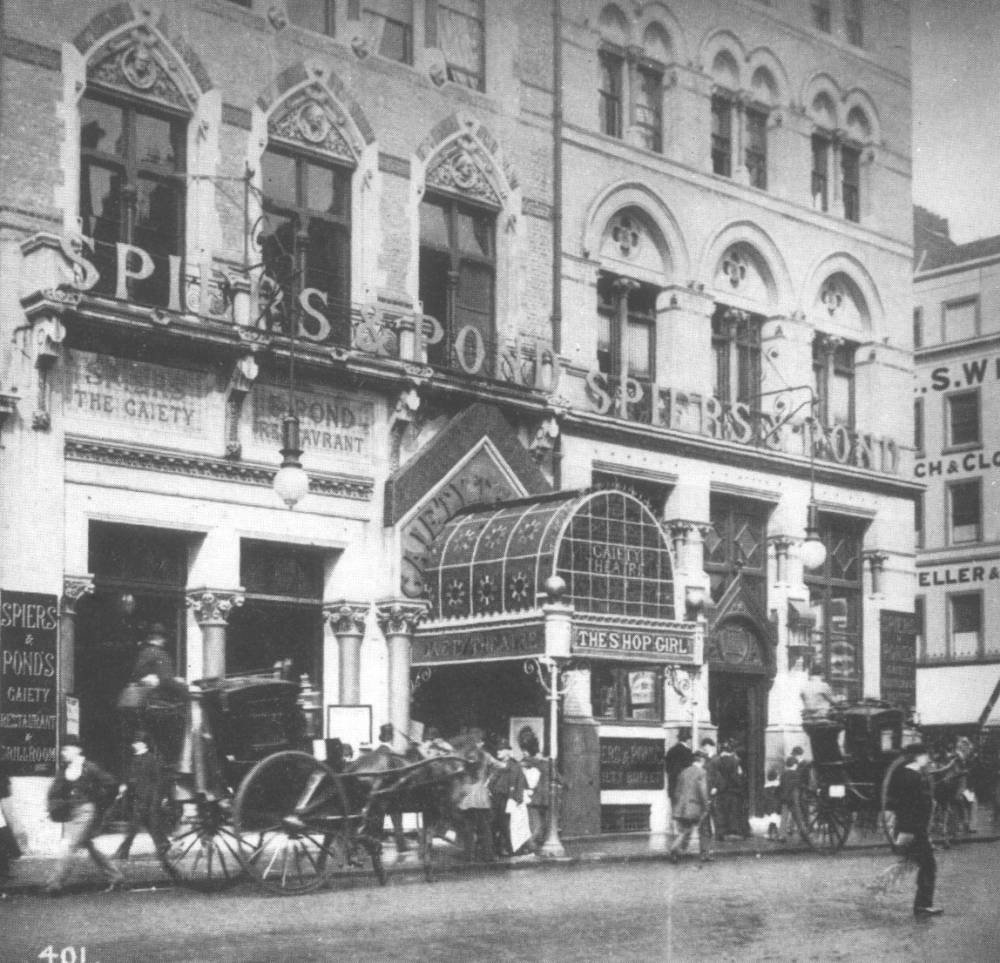

The Gaiety Theater in 1901. The front of the marquee shows that the theatre, which was demolished in 1903, was showing The Toreador, the final musical comedy performed there. Click on image to enlarge it.

John Hollingshead, manager of the Gaiety Theatre from its opening in 1868 until his retirement in 1886, credits his successor, George Edwardes, with the invention of musical comedy: “The invention or discovery of Musical Comedy was a happy inspiration of Mr. George Edwardes’s. It provided a new form of entertainment for playgoers who go to a theatre for amusement and recreation, which was more elastic in plot or story than the old burlesque. These were generally tied to some well-known tale or legend.”3 Hollingshead cites the death of the celebrated comedian Fred Leslie as a factor forcing a change from the old burlesque, and it was compounded by the protracted illness of burlesque star Nellie Farren (Hollingshead, 70).

At this point, I should stress that the entertainment labelled “burlesque” at the Gaiety in the 1870s and 1880s was not of the kind denoted by the same term in the USA (and nowadays in the UK, also). Gaiety burlesques were at first short parodies of operas or myths, becoming longer in the 1880s. Edwardes first chose to experiment with his new ideas at the Prince of Wales’s Theatre rather than the Gaiety, because of the latter’s strong association with burlesque. While the burlesque Cinder-Ellen up Too Late was playing at the Gaiety, In Town opened at Prince of Wales’s Theatre on 5 Oct. 1892. It was called a “musical farce” rather than “musical comedy,” but it is really the first example of the new genre. The book and lyrics were by James T. Tanner and Adrian Ross, and the music by F. Osmond Carr.

The star of the show was comedian Arthur Roberts, and the co-star was Florence St John, who had sung in opera. In other words, it contained the mixture of actor-singer and singer-actor familiar from operetta. The Sunday Times described it as “a curious medley of song, dance and nonsense … and the very vaguest attempt at satirizing the modern masher.”4 Alan Hyman says that all the women in the cast were dressed in “Bond Street creations in the height of fashion,” and that the men “looked as if they had just walked in from Savile Row” (64). The show’s novelty lay in its present-day setting and its engagement with modernity and fashion. Out went the tights for women and eccentric clothes for men, and in came haute couture dresses and Savile Row suits. Musical comedy reversed the relationship that had hitherto existed between the stage and the fashionable world. Instead of imitating that world—as the music-hall “swell” imitated the London dandy—it was now the fashions seen on stage that were imitated by society women and stylish young men of the West End.

The curly brimmed top hat worn by Robinson as Captain Coddington was soon known as the Coddington hat and worn by West End mashers—anticipating the female demand for the Merry Widow hat in the next decade. In this decade, the term “masher” indicated a dandy philanderer, although, as the years went by the term grew more negative, suggesting someone prone to making inappropriate sexual advances. The conundrum faced by Captain Coddington is that he invited all the young women of the Ambiguity Theatre to lunch without the wherewithal to pay for them. Lord Clanside offers to fund the lunch provided he is invited, too. The Sunday Sun found this show “the brightest, raciest, and spiciest” musical entertainment in the West End.5 The Era, however, accused it of creating “an atmosphere of vulgar, venal vice,” in depicting women chasing after men.6 This periodical, of course, found nothing insalubrious about men chasing after women. The Players magazine commented that the eyes of many women in the audience “grew large with envy” at some of the fashionable frocks on display (quoted in Mander and Mitchenson, 13). This comment indicates that an appeal was already being made to the feminine gaze in the 1890s—and this was something that grew stronger in the next decade, as evidenced by the advertisements placed in theatre programmes. In confirmation of the show’s modernity, the Players magazine remarked that it embodied “the very essence of the times in which we live” (quoted in Mander and Mitchenson, 14). It transferred to the Gaiety in December 1892, and enjoyed a total run of 297 performances. In August 1897, it was revived at the Garrick, in preparation for a New York production at the Knickerbocker Theatre the following month.

Fig.1 Cover of vocal score of A Gaiety Girl. Click on image to enlarge it.

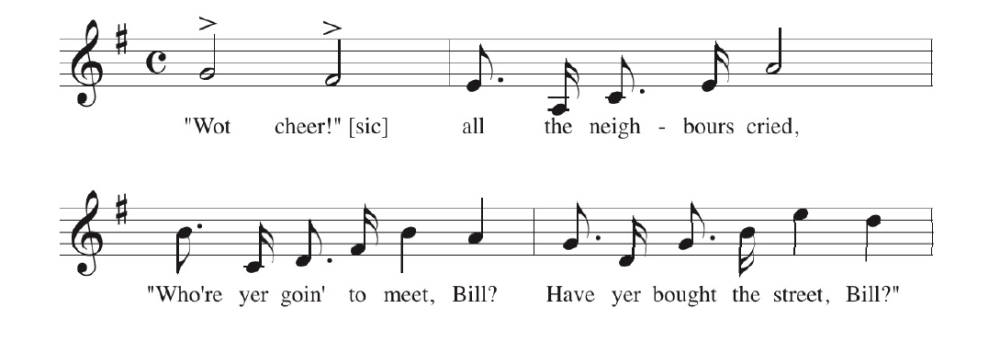

The first production to be labelled a “musical comedy” was A Gaiety Girl, which opened at the Prince of Wales’s Theatre on 14 Oct. 1893, and transferred to Daly’s Theatre on 10 Sep. 1894, gaining a run of 397 performances in all. The book and lyrics were by Owen Hall, and the music by Sidney Jones (Fig. 1). “Owen Hall” was a pseudonym chosen by Jimmy Davis, because he was frequently in debt, “owing all” to his creditors (quoted in Hyman, 67). The plot was slight, and a contemporary description noted that the show was an assortment of “sometimes sentimental drama, sometimes comedy, sometimes almost light opera, and sometimes downright ‘variety show’.”7 The variety elements extended to the incorporation of a music-hall style at times, as in For instance, the common time song with dotted rhythms found in the “Cockney” songs of Albert Chevalier, such as “Wot Cher (Knock’d ’em in the Old Kent Road)” of 1891 in heard in “Jimmy on the Chute, Boys!” (see Ex. 1 and Ex. 2).

A mixture of styles was typical of musical comedy, which was in competition not only with burlesque but also with comic operas at the Savoy. Edward Solomon’s The Nautch Girl had finished a successful run at that theatre in January 1892, Sullivan and Grundy’s Haddon Hall ran there from September 1892 to April 1893, and Gilbert and Sullivan’s Utopia Limited opened the week before A Gaiety Girl. It ran into some preproduction censorship difficulties, because it appeared to satirize a living judge, and because its dialogue was occasionally racy. The censor did allow the following exchange:

Lady Virginia: Marriage is an ancient institution, divorce is a mere mushroom.

Mr Justice Grey (with a leer) And, like a mushroom, it often springs up in a single night.

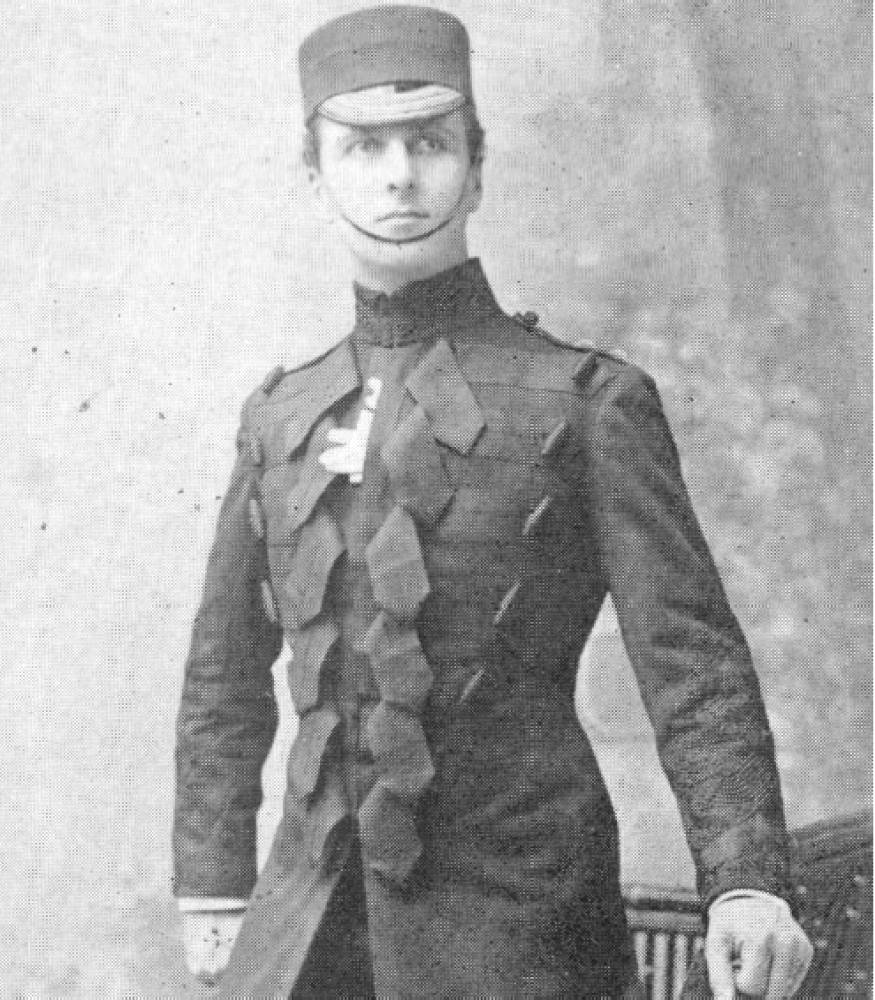

There were two glamorous leads: Marie Studholme and Hayden Coffin. Figure 2 shows Hayden Coffin in his role as Captain Charles Goldfield. It also had lots of chorus girls in various changes of costume. Not only was this production the first to be described as a “musical comedy,” but it also set a precedent for using the word “girl” in a title, and established the modern image of the Gaiety girl.

Fig. 2 Coffin as Charles Goldfield. Click on image to enlarge it.

Edwardes made sure the young women in his chorus all received training in elocution, dancing, and elegant deportment. The image worked wonders, and a number of them married into the aristocracy. It was not always what every member of a particular aristocratic family may have wished, but those who chose to be positive about it saw marriages to stage performers, and, for that matter, Americans, as a means of strengthening the blood line against any inherited weaknesses. A Gaiety Girl was another slice of modernity, a “comedy of modern life,” as The Era put it (Mander and Mitchenson, 16). Edwardes quickly decided should go on tour to New York and elsewhere abroad. The musical director for the Australian tour was Granville Bantock—a fact strangely absent from his Wikipedia entry, despite his having written a book about it in 1896 (Round the World with “A Gaiety Girl”).

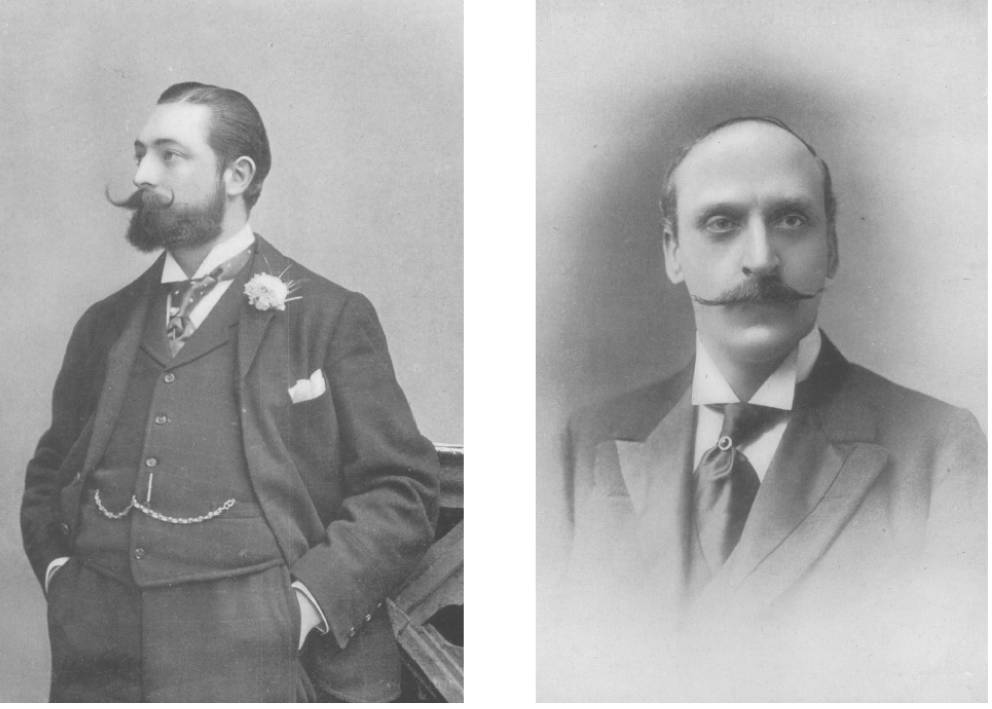

Edwardes had now gained sufficient confidence to premiere a new musical comedy at the Gaiety. The Shop Girl opened there in November 1894, and, like In Town, it was described as a musical farce. The book was by Henry Jackson Wells Dam, who claimed to have researched his subject in Whiteley’s department store and the Army and Navy stores in order to capture “the life of today.”8 The music was by Ivan Caryll, with additional numbers by Lionel Monckton to lyrics by Adrian Ross. Caryll’s birth name was Félix Tilkin; he was Belgian and had studied at the Paris Conservatoire. Monckton had studied Law at the University of Oxford. Caryll handled the trickier concerted sections, such as finales, but Monckton often came up with the catchier tunes for individual songs. There was certainly competitiveness in the relationship of Caryll and Monckton, and it appears to have extended to their respective abilities to wax a moustache (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Ivan Caryll and Lionel Monckton. Click on images to enlarge them.

The Shop Girl was an enormous success, running to 546 performances, and firmly established musical comedy as the most popular stage entertainment in the West End. There was a link between the big shops and the theatre, because affluent women from the suburbs would often combine a shopping trip with a visit to the theatre. Both of these activities were respectable, although both might involve chance interactions with men.

The two leading roles were taken by Ada Reeve, a music-hall singer, playing the shop girl Bessie Brent, and Seymour Hicks, who, at this time was a comedian with little singing experience. Ellaline Terriss, Hicks’s wife, replaced Reeve, who had already been pregnant went she took on her role. Her obtaining the role had nothing to do with her husband pulling strings (you’ll find further resonances of this metaphor later in my paper). She had already been hired by Edwardes as “leading lady” at the Gaiety, and at £25 a week, was earning almost twice as much as her husband.9 Terriss had the unusual distinction of having been born in Stanley on the Falkland Islands. Her father, formerly an actor in London, had been seized by a sudden desire to become a sheep farmer in a distant land. Her parents returned with her to England when she was only two weeks old, so you might ask if being a Falkland Islander had any effect on her later career. All I will say is that she confesses in her memoirs to having amassed a collection of over 300 model penguins.10

Like his wife, Seymour Hicks had been born on an island, but one closer to London, in the shape of Jersey. He gained experience as a playwright and comedian before developing skills as a singer and dancer at the Gaiety, and then becoming an actor-manager and producer. In The Shop Girl, his song “Her Golden Hair Was Hanging down Her Back” was considered risqué. He and Adrian Ross adapted it from a recent song by music-hall entertainer Felix McGlennon. The variety elements present in musical comedy meant that a song reminiscent of the style of the music hall or American vaudeville did not jar as it would have done in stage work more closely associated with comic opera or operetta. The respectability of women who attended musical comedy could be much more relied upon by theatre managers than that of those who attended the music hall. In the latter environment, hair hanging down a woman’s back carried a strong connotation of impropriety. Theatre historian Peter Bailey cites a report that appeared in the Evening News the month before the premiere of The Shop Girl, which stated that women with “loose, unbonneted hair” were being denied admission to the Empire Theatre. This was a variety theatre in Leicester Square, managed by George Edwardes, but which was at this time the subject of scandal regarding prostitution.11 There is a reference in Hick’s version of “Her Golden Hair” to Mrs Chant, that is, Laura Ormiston Chant, who was prominent in the moral campaign against the Empire Theatre.

The first act of The Shop Girl was set in a department store and the second in a bazaar. Department stores were a feature of cosmopolitan modernity: the opening chorus informs us, “Ev’ry product of the planet / Since geology began it” can be bought on one or other of its “mile on mile of floors.” The possibility of Gaiety girls marrying into the nobility is hinted at in the song “The Smartest Girl in Town.”

And the millionaires devotedly adore me

And the peerage in a body kneels before me,

And the little dancing girl may be married to an Earl,

For you never, never, never, know your luck.

Women were no longer typically portrayed as passive. Miggles, a shopwalker at the shop, whose job is to supervise the sales staff, sings about being forced to become a vegetarian by his new wife:

For breakfast we had porridge for dinner we had fruits,

Oh woe! woe the day!

And if we had a supper it was principally roots,

Yea, verily yea!

Sadly, after all his suffering, his wife elopes with a butcher.

Fig. 4 Grossmith as Bertie in The Shop Girl. Click on image to enlarge it.

The newly wealthy American is presented in the song “The Millionaire,” in which Bunco Brown tells of how he transformed himself from a desperado in the gold mines to “plutocratic Brown of Colorado.”

The Shop Girl witnessed the stage debut of George Grossmith Jr, son of a famous comedian, and known as Gee-Gee to his friends. He played the masher Bertie Hoyd, the cut of whose coat was “quite the thing.” His masher song “Beautiful Bountiful Bertie,” composed by Monckton to Grossmith’s own lyrics, proved to be another of the show’s hit numbers. Figure 4 depicts Bertie in his fashionably cut coat.

Bertie has the onerous duty of escorting a group of foundling girls around town (Fig. 5). This was the first musical comedy to have a full chorus line of elegantly dressed modern Gaiety girls. However, it played safe by having a scantily clad burlesque troupe of women appear in Act 2. In other respects, the production of the show followed the usual Gaiety procedure: Pat Malone and Sydney Ellison took charge at first, and then Edwardes would turn up to the final rehearsals, making comments and offering advice that was always found to deliver significant improvements.

Fig. 5 The foundlings, from The Shop Girl. Click on image to enlarge it.

At Daly’s Theatre in the year The Shop Girl had its premiere, there was a production of An Artist’s Model, which had a book by Owen Hall, and music by Sidney Jones. It starred Marie Tempest and Letty Lind. Its description as a “comedy with music” was assumed to mean something akin to light opera or operetta. Edwardes was inclined to give distinction to this theatre by moving in an operetta direction.

The most successful of all Daly’s productions in the 1890s was The Geisha, which opened there on 25 April 1896 and ran for over two years, notching up a remarkable 760 performances. The book and lyrics were by Owen Hall and the music by Sidney Jones. Marie Tempest was the Geisha, and it also featured Letty Lind, Hayden Coffin, and Huntley Wright. The description “musical play” was used for the first time. This could be synonymous with operetta in the next decade and beyond. In a musical play, romance took precedence over comedy, and a higher standard of singing was expected. Tempest and Coffin were both very capable singers, and the show proved a triumph for Tempest.

Edwardes hired Arthur Diósy, founder of the Japanese Society, as a consultant (Hyman, 80). Even the choreographer was at pains to study dances at the Japanese exhibition village in London (Platt, 66.). Japanese merchandizing took over the West End while the show was running. Whatever the extent of genuine interest in other cultures may have been, however, musical comedy always promoted the British imperialist belief in modernity and progress. The Geisha may have served up escapism and romance, but the fantasy was realized in terms of modern spectacle, using innovative design and lighting, and the latest stage technology. Moreover, its creation, production, and marketing related to values that were unmistakably, urban, industrial, and consumerist. There is no doubt, either, that Orientalist attitudes persist in The Geisha, despite attempts to capture something “authentic” about Japanese culture. At times, there is even a lapse into crude stereotyping, as in the song “Chin Chin Chinaman.” Some years ago, I spotted a recording of an old German radio broadcast of Die Geisha. I bought it instantly, and I couldn’t wait to get back home to see how the “Chinaman” song was translated into German. I discovered that this was the only song in the piece retaining its original English text—a neat way of telling the British, “you’re the racists, not us.”

I want to single out one number from The Geisha to compare ironic sentimentality in the Savoy operas with that in musical comedy. It seems appropriate to choose a song from Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado to set alongside one from The Geisha. In the words and music of “Tit Willow” there is never any direct hint that the sentimentality is anything other than sincere. The audience has to recognize the double-voiced coding of ironic discourse without any help from anyone familiar with Bakhtin or poststructuralist theory. At first, it appears that the same approach to ironic sentiment is being taken by Hall and Jones in “The Amorous Goldfish” (Ex. 3). The feeding of the goldfish’s “small inside” with “crumbs of the best digestive bread” must have alerted the audience to its being a mock-pathetic ballad with deliberately exaggerated sentiment. Gilbert and Sullivan, who might be said to have created the genre of the mock-pathetic ballad, introduced similar inflated sentiment in “Tit Willow” (the bird “slapped at his chest,” and “a cold perspiration bespangled his brow”). Yet, they keep a straight face to the very end of the song, giving no indication that they imagine members of the audience might not take the fate of the little bird seriously. However, Hall and Jones, in “The Amorous Goldfish,” betray an expectation that the audience will react with knowing laughter at having their feeling manipulated. When her glass bowl is knocked over and the lovesick goldfish dies on the carpet, the lyrics admonish the audience as follows.

Fig. 6 Ellaline Terriss with her little piece of string. Click on image to enlarge it.

Statistics for numbers of performances on the German stage show that, of musical stage works composed between 1855 and 1900, The Geisha was second only to Die Fledermaus in popularity during the first two decades of the twentieth century.13 It also enjoyed great success in France and the USA, and throughout the British Empire. Perhaps more unexpectedly, it was also a hit in South America, Italy, Russia, Scandinavia, and Spain (Platt, 38). Two new Musical comedies given at the Gaiety in 1896 were My Girl and The Circus Girl. The latter was another Caryll and Monckton collaboration, and had a book by Tanner. The stars were Ellaline Terriss, Seymour Hicks and comedian Connie Ediss. I have a slide of Hicks and Terriss. Once more, Monckton succeeded in providing the hit song, when Terriss sang “Just a Little Piece of String.” In Figure 6 she is, showing it off — it’s the metaphorical leash she keeps her husband on. I promised I would return to the trope of “pulling strings.” Terriss was so much associated with this song that she used its title for her memoirs.

Connie Ediss, whose stout physique and humorous persona is a reminder that there was still room for the character actor among the glamorous figures on stage, sang “The Way To Treat a Lady,” which told of her being left in a pub by her husband, who didn’t even pay for her glass of port and lemonade.

It must have now become obvious how popular the word “girl” was in the title of a musical comedy. The labelling of young women as “girls,” has been described by Peter Bailey as a strategy to frame them as “naughty but nice.”14 The Gaiety Girl was not prim or over-zealous in religion and politics, nor intellectually ambitious in the manner of the New Woman of the 1890s. The Gaiety Girl may not have been an example of the New Women, who spurned fashion and regarded marriage as something that stifled careers and ambitions, but she was certainly an example of the modern woman, a woman who knew her own mind and was not inclined to passivity in her dealings with men. This did not put men off: the term “Stage Door Johnnies” was used at this time to refer to those men who would crowd outside the stage door hoping to escort one of the young women to supper at a popular nearby restaurant, such as Romano’s, Gatti’s, or Rules (the latter is still standing in Maiden Lane).

Young women of a higher social status than hitherto were taken by the idea of being chorus girls. They were no doubt drawn by the attractive costumes and elegant deportment of the new type of Gaiety girl, as well as the knowledge that their company was often sought by men of high social standing. The modern Gaiety Girl had a striking impact because she was dressed as a fashionable woman about town, rather than in any kind of obvious stage costume. There were auditions held every week, and a turnover was fairly rapid because, whatever talents such women possessed would never overrule the essential factor that they must be young, and, to put it bluntly, appeal to the gaze of the drooling mashers or would-be mashers in the audience. Figure 7 shows the six Gaiety girls of Lady Coodle’s party in A Runaway Girl, produced in 1898.

Fig. 7 Lady Coodle’s girls. Click on image to enlarge it.

The basic weekly wage of a Gaiety chorus girl was £2. 10s. However, Edwardes took care to promote and reward, and those in his privileged group known as the “big eight” could earn up to £15 a week (Hyman, 96). She could also be given a chance to shine in a solo role. There were, of course, chorus boys, but much less comment is made about them. In musical comedy, the female characters are generally more strongly drawn than male characters, and they are usually active and confident.

The Runaway Girl was a runaway success, with a New York production in the same year. The book was by Seymour Hicks and Harry Nicholls, the lyrics by Aubrey Hopwood and Harry Greenbank, and the music by Ivan Caryll, again with the assistance of Monckton (Fig. 4). The team involved in creating the words and music may be interpreted either as indicating that a new kind of art world is emerging, or alternatively, as representing the division of labour that characterizes industrial production methods.

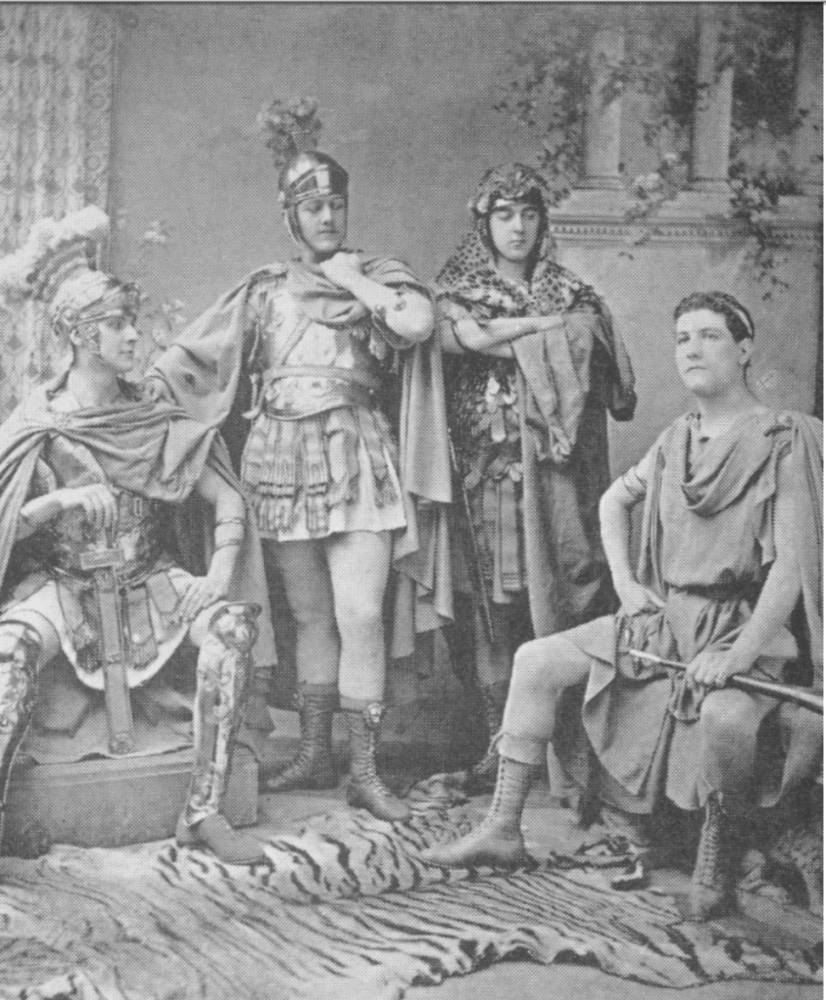

Fig. 8 Daly’s boys: the patricians in A Greek Slave. Click on image to enlarge it.

While The Runaway Girl was delighting audiences at the Gaiety, George Edwardes seems to have lost his superstition that the word “girl” was need in a title for a show to be successful. The title role of A Greek Slave, which premiered at Daly’s on 8 Jun. 1898, was given to Hayden Coffin. A sign that musical comedy had fully overtaken Savoy-style operetta was that Rutland Barrington, a leading performer with D’Oyly Carte, left that company to play Marcus Pomponius. Good singing was called for and the leading female role of Maia was given to Marie Tempest. In this production, Monckton was providing additional music to that of Sidney Jones. The book was by Owen Hall, with lyrics by Greenbank and Ross. Boys and girls now began to find themselves on show to an audience gaze so mixed, it is probably safer not to try to gender it. The Patrician boys of A Greek Slave are revealed in Figure 8. The word “boy” was used for the first time in the Gaiety production of The Messenger Boy in 1900, which had music by Caryll and Monckton.

Fig. 9. Marie Tempest as San Toy disguised as a boy. Click on image to enlarge it.

We may be tempted to ask if there were moments, amid all this masculinity and femininity, that we might place under a queering lens. Let’s consider San Toy, which opened at Daly’s on 2 Oct. 1899. Many in the creative team are familiar: the book is by Edward Morton, lyrics are by Ross and Greenbank, and the music is by Jones. Rutland Barrington is again in the cast, and also Huntley Wright. Marie Tempest, plays San Toy, the Chinese title character. She appears first as a boy and, in Len Platt’s words, “has something approaching a love scene with her female friend Poppy;” in addition, her love affair with Bobby carries homoerotic overtones, since both are represented as male (Platt, 112).

Marie Tempest, whose family name proved to be an example of nominative determinism, had strong feelings about the Chinese trousers she had to wear in disguise as a boy. She wanted to wear tights and short trunks, but Figure 9 shows They may not look particularly long, and it looks as if she has turned them up, because they were supposed to be knee length—and, indeed, they appear so on a poster picture.26=15 Anyway, she took a pair of scissors and cut them even shorter. When Edwardes told her that she had to wear the correct costume, she was furious and replied that she would quit the show, which she did soon after.

The Toreador, was the final musical comedy produced at the Gaiety, it ran from June 1901 to July 1903, after which the theatre was demolished and the new Gaiety built nearby. Gertie Millar made her triumphant London debut in this show, bringing what she ended up with fresh vivacity to the image of the Gaiety Girl, and establishing herself as the new leading star of musical comedy.15

I will end with some general remarks about musical comedy. It is possible to find occasional use of the term “musical comedy” that predates the Edwardes productions,16 but it is what the term meant in the context of the modern Edwardes shows that gave it a distinctive meaning. Here, thinking of the title of my essay, I should explain why I am happy to speak of modernity, but not modernism. It is because there is no attempt to apply the ideas of artistic or aesthetic modernism in these shows. There is no concern with innovation, experimentation, or progress in terms of musical style. There may be a desire to emulate fashionable musical style, but not, say, the style of Richard Strauss’s Don Juan of 1888, a tone poem described by Carl Dahlhaus as “a musical symbol of fin-de-siècle modernism.”17 For Len Platt, musical comedy offers a strong reminder that there was a mainstream in the culture of the 1890s that “formulated modern times in ways that were often at odds with more intellectual cultures.”18

Musical comedy appealed, in the main, to the middle class and the lower middle class. The presence of the latter in West End theatres should not be underestimated. All of those theatres have more cheaper seats available than expensive seats, just as an aircraft today has more economy seats than business class seats. Nevertheless, the subject position of musical comedy was bourgeois, and this is revealed by the necessity for its aristocratic stage characters to adapt to the new wealth and influence of the middle class, and by the need for the working-class characters to take on bourgeois values of respectability. Musical comedy continued to be successful in the new century, until enthusiasm for operetta from the German stage took over the West End following the sensational success enjoyed by The Merry Widow at Daly’s in 1907. Since then musical comedy has been one of the most neglected genres in British theatre history, and I would want to conclude by insisting that its neglect is undeserved.

Last modified 29 July 2018