ometimes the Guardian art critic Jonathan Jones’s judgements are spot on: the brutal political undertow of Soviet propagandist art and the useful idiots who propounded it. Or – a major concession from me – how he feels Victorian sculpture looks so ‘last year’ once you’ve encountered a knockout Hawaiian feather head at the current Royal Academy exhibition Oceania. But he gets it badly wrong in his review of the 2018 Tate Britain Edward Burne-Jones exhibition. Jonathan has failed to do his homework, hence my title. I may not convert him, and I may be preaching to the converted here. Whatever, let’s get started in this consciousness-raising exercise…

1. “To put it bluntly, Burne-Jones is a stupid artist”

Isn’t the boot – or medieval sandal – on the other foot? The exhibition intelligently vindicates Elizabeth Prettejohn’s point in her catalogue essay: “Burne-Jones approached art-making rather as a philosopher in the new discipline of aesthetics to find what out what is beautiful” (p. 15). He is one of a kind in having studied theology and classics at Oxford and not having been tainted by a formal, academic art education, grinding the originality and creativity out of him. His learnedness is manifest in his often complex iconography, whose pictorial storytelling Prettejohn likens to “intertextuality”, “a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings… blend and clash” (p. 17).

Left: The King and Cophetua. Right: Laus Veneris. Click on these and following images to enlarge them.

Burne-Jones can be as complex and abstruse (think Sidonia von Bork and The King and Cophetua) or else as simply formally beautiful as the beholder wishes. If you don’t have Wilhelm Meinhold or even Alfred Tennyson on your lips, Jonathan, and you don’t feel like looking in order to see, then maybe you are left cold. But for me, operating on these two levels, the first cerebral and literary, the second affectively (and effectively) visual, makes Burne-Jones so compelling. He is elitist yet accessible. He is intellectually layered, yet his work appeals for the art’s sake. He is faithfully figurative, and yet he is dreamy and otherworldly – hence a cult figure among trendy fin de siècle French and Belgian symbolists. He is understated and near monochrome, but in Laus Veneris, he is little short of psychedelic. He is intensely private and hermetically sealed from the world, yet he wanted working-class people to see his art, share his dream, let a little beauty enter their lives, and say “Oh! – only Oh!” before them (Prettejohn, p. 19). Our more hyperbolic age would probably translate this as “Wow!”

2. “His first paintings are as mature as he will ever get”

“After embracing the style of Dante Gabriel Rossetti… in his 20s, he carried on ploughing the same dreary furrow until his death” Definitely wrong! Sure, Rossetti was a powerful, indeed formative inspiration. “I wonder what Rossetti would have said to this” is a question Burne-Jones forever asked (Prettejohn, p. 18). But, as emerges even from the first gallery, within a few years of Burne-Jones belatedly taking up art, a range of carefully considered influences, both intellectual and formal, is clearly in operation too. One of them is an elephant in your room, Jonathan, a certain John Ruskin. Others, doubtless recommended by that Venetian-stoned critic, include Giorgione, early Titian and Veronese. Before the early 1870s are out, add Signorelli, Michelangelo and – here he was one of the earliest to rediscover his genius – Botticelli – to the Burne-Jones style. Like Henry Moore in the following century, he synthesises something uniquely his own out of these diverse ingredients.

Early on we witness not instant maturity but a near miraculous evolution from the clunky if compelling claustrophobia of Buondelmonte’s Wedding to The Lament, which is at once sparing, haunting and ambiguous, both iconographically and sexually. Here Burne-Jones’s mature style is indeed announced. And though he may go on to plough a similar furrow, does that in itself condemn him? Shouldn’t we get equally bored with Giorgio Morandi’s subtly compelling still lifes, Mark Rothko’s breathtaking hazes, or Moore’s signature reclining figures? Possibly the last is boring because he’s British. Jonathan’s review is a classic instance of what I diagnose as ‘the Britishness of knocking British art’.

Left: The first painting in the Perseus Series. Right: Souls on the Banks of the Styx.

At what is perhaps the climax of the exhibition – the long-awaited reunion of the Perseus and Briar Rose paintings series (see Prettejohn 121-146), we meet the monochrome Burne-Jones and the multicolour Burne-Jones, the active and the passive Burne-Jones, the vertical and the horizontal Burne-Jones. And then in the final gallery, the multimedia Burne-Jones, artist-craftsman of books, stained glass, tapestries, furniture decoration and oil painting, comes powerfully and beautifully into his own (see Cooper 197-204). If you’re willing to take this to a still further iteration, Jonathan, then consider the entirely distinctive, bleak, late Burne-Jones style, exemplified in The Dream of Launcelot at the Chapel of The San Graal or the unintentionally expressionist and powerful, unfinished Souls on the Banks of the Styx. Critics were baffled by such works, the public didn’t like them much either, but Burne-Jones was true to his artistic integrity, doing his own thing and never pandering to popular whims.

3. Burne-Jones’s Portraits

“I was startled to see a painting I give a damn about… a portrait of William Graham.” This portrait (see Gere 148) is indeed compelling, though it is a frankly minor work, despite the huge part that this generous, patient, tasteful patron played in bankrolling Burne-Jones during his years of obscurity (1870-77), when he temporarily ceased exhibiting in public. If Graham looks “utterly tortured” (Jones), then it is because this portrait reflects the ill-health that preceded his death in 1885. Jonathan misses out on the revelatory qualities of other works in this small gallery. We encounter a reluctant portraitist who snatches memorable victory from awkward defeat. The delightful Portrait of Katie Lewis, with her artfully placed lapdog and orange is fairly well-known, but less so the otherworldly Ignacy Paderewski, whom you would swear was created to be painted by Burne-Jones. And then there is the exquisite, pallidly Proustian Baronne Madeleine Deslandes, whose defiantly anti-realist hands seem wrought from porcelain.

4. Burne-Jones’s Relation to Modern Art

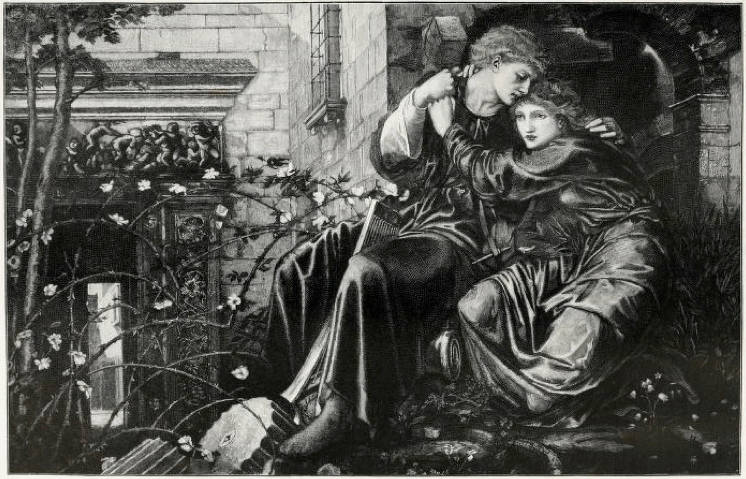

Left: The Golden Stairs . Right: Love Among the Ruins.

“For his enthusiasts, Burne-Jones [is] the forbear of modern art.” Jones then compares The Golden Stairs with Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2 (a familiar trope) and concludes: ‘It doesn’t make Burne-Jones the inventor of modern art’. I agree, but Burne-Jones’s relationship with modernism is altogether more complex and subtle than that and can’t be so airily dissed. Let me write a Ruskinian-length sentence to explain how and why. In his exceptional background mentioned earlier (Oxford; self-taught); in his lifelong opposition to the academy, its values and class system; in his related belief in the primacy of decorative art over fine art (a point rightly emphasised in the exhibition); in his highly idiosyncratic blurring of media – watercolour and bodycolour that were mistaken for oil paint in Love Among the Ruins; in his art for art’s sake formalism, which Roger Fry himself had hoped to analyse before his untimely death; in the abstract seriality of his The Morning of the Resurrection; in the proto-surrealism of the huge shield stuck in the boughs of a dead tree in The Dream of Launcelot at the Chapel of the San Graal, and the inventive lunar landscapes in the Perseus series; and obviously his Art Nouveau avant la lettre in The Pelican in her Piety; in all these things, I verily say unto thee, Burne-Jones is a significant forbear of modern art.

The Morning of the Resurrection.

But as we see from his disavowal of Aubrey Beardsley and his deeper realisation late in life of the threat posed by Impressionism and early Post-Impressionism, Burne-Jones would never have regarded himself as furthering any kind of modernist cause: perish the thought. At heart, his art was simply too beautiful and finished for a modernism which mostly (Constantin Brancusi excepted) challenges and undermines the exquisite crafting that underpins almost everything that Burne-Jones touched. Pace Nicholas Tromans in his otherwise admirable catalogue essay, it makes perfect sense that Philip Burne-Jones should “join in the ignorant [sic] denunciation of the new styles – cubism, fauvism and the like, as degenerate” (p. 36). His late father would have expected nothing less of him.

5. Burne-Jones, Darwin, and Victorian Crises of Belief

“Burne-Jones was a contemporary of Darwin but evolution passed him by.” Since when is art supposed to mirror the Zeitgeist in this crudely deterministic way? Does this make William Dyce’s Pegwell Bay, Kent, a Recollection of October 5th, 1858 Jone’s favourite nineteenth-century painting? (I wish!) But let Burne-Jones answer this himself: “The more materialistic science becomes, the more angels shall I paint.” He did so defiantly and gloriously till the end, with Angeli Ministrates and Angeli Laudentes Angeli Ministrates appearing first as stained-glass windows and then as tapestries.

Left: Angeli Ministrantes. Center: Angeli Laudantes (detail). Right: Angeli Laudantes.

Like his lifelong friend William Morris, though rather less fiercely, Burne-Jones moved on from his orthodox High Anglican faith at some indeterminate point in the 1860s. Here we cannot altogether rule out the intellectual influence of Charles Darwin and all his nineteenth-century predecessors who undermined Victorian faith in the literal truth of scripture, even if this is undocumented. But it was really much more a case of finding a new faith and mission in art. Burne-Jones certainly didn’t jettison religion altogether, declaring: “I love Christmas carol Christianity. I couldn’t do without medieval christianity” (see Wildman and Christian 319). Some may sneer but I completely identify with this sentiment. I felt similar thoughts when I attended choral evensong as a student at King’s College, Cambridge, contemplating the fan vaulting and stained glass. Doesn’t Burne-Jones yet again strike a modern note? Much more could be said about the need to produce spiritual art in a secularising age: here it is enough to note that designing stained-glass windows more than any other art form kept Burne-Jones’s body and soul together. A catalogue chapter on his art, faith and spirituality would have been most welcome.

6. Burne-Jones, Wilde, and the Aesthetes and Decadents

‘What Burne-Jones needed, apart from a slap in the face with a wet fish, was to read more Oscar Wilde’. A Wildean bon mot indeed! But it’s also historically crass. Picture of Dorian Gray, his recommended reading from Jones, appeared in 1890, less than ten years before Burne-Jones’s death and at the zenith of his international acclaim. Burne-Jones was born 21 years before his fervent admirer Wilde (!) and contributed, probably not always to his comfort, to the importance of Wilde. It's unfashionable to say this, but I can sympathise with Burne-Jones’s worry, late in life, that the Wilde scandal risked bringing his older, gentler aestheticism into disrepute. Burne-Jones’s kindness to Constance Wilde, who is cruelly marginalised by some Wildeans, is well documented (see McCarthy 450). If there are literary affinities between Burne-Jones and his contemporaries, then they are with the pioneering art for art’s sake of A.C. Swinburne and the sensibilities of Henry James . The latter had no doubt that ‘Mr. Burne-Jones stands forth both as a great inventive genius and as one of the most complete masters… of the expressive, the designing, the characterising part of draftsmanship’ (see Smith 125). ‘The Master’ graciously acknowledges his peer, and Oscar is irrelevant here.

7. What? No Mention of the Magnificent Drawings?

Every reviewer is constrained by word limits and as a relatively experienced hack myself, I have my sympathies. Yet there are some serious omissions in the review. That of drawing – which goes unmentioned — is startling, as it constitutes, per capita, the most gorgeous gallery of the exhibition. “Line flowed from [Burne-Jones] almost without volition”, claimed his friend Graham Robertson (see Wildman and Christian 149). If there was anything that I coveted to the point of staging an American Animals-style heist, I told chief curator Alison Smith that my sights were on four grouped drawings: Study of female head to right, The Head of Cassandra, the appropriately-named Desiderium, and Maria Zambaco (see Cruise 107). She sympathised.

Burne-Jones’s transgenderism would require a separate review but it strikes an uncannily topical note in a way that couldn’t have been anticipated even five years ago. It is partially addressed in Tromans’ essay with some nastily juicy quotations reflecting anti-Burne-Jonesian homophobia. But how could any Guardian contributor overlook this contemporary issue?

Finally, you don’t need to be LGBT to get a special kick out of B-J. You can be a J.R.R. Tolkein buff too. Add to this the films of my compatriot Peter Jackson, Game of Thrones, and for older gamers, Dungeons and Dragons. As Tromans astutely observes: “The legacy of Burne-Jones for popular fantasy imagery and literature in the twentieth century would be interesting to explore” (p. 37). May the force be with any PhD student who undertakes this journey!

Related material

Bibliography

Burne-Jones, Georgiana. Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, Vol. II. London: Macmillan, 1904. Internet Archive. Contributed by Brigham Young University. Web. 28 October 2018.

Cooper, Susan Fagence. “Burne-Jones as Designer.” Smith, 197-213.

Cruise, Colin. “‘An impassioned imagination’: Burne-Jones as a Draughtsman.” Smith, 75-121.

Gere, Charlotte. “Burne-Jones as Designer.” Smith, 197-215.

Jones, Jonathan. ‘Edward Burne-Jones review – art that shows how boring beauty can be’, Guardian (22 October 2018). Online version.

McCarthy, Fiona. The Last Pre-Raphaelite: Burne-Jones and the Victorian Imagination. London: Faber & Faber, 2011.

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. “Burne-Jones: Intellectual, Designer, People’s Man.” Smith, 13-21.

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. "The Series Paintings." Smith 169-95.

Smith, Alison, ed. Edward Burne-Jones. London: Tate Publishing, 2018.

Tromans, Nicholas. "'Girlish Dreams': Burne-Jones in the Twentieth Century." Smith 35-41.

Wildman, Stephen and John Christian, eds. Edward Burne-Jones: Victorian Artist-dreamer. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998.

Created 19 November 2018